Habitat fragmentation mediates the mechanisms underlying long-term climate-driven thermophilization in birds

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

eLife Assessment

This fundamental study substantially advances our understanding of how habitat fragmentation and climate change jointly influence bird community thermophilization in a fragmented island system. The authors provide convincing evidence using appropriate and validated methodologies to examine how island area and isolation affect the colonization of warm-adapted species and the extinction of cold-adapted species. This study is of high interest to ecologists and conservation biologists, as it provides insight into how ecosystems and communities respond to climate change.

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

Climatic warming can shift community composition driven by the colonization-extinction dynamics of species with different thermal preferences; but simultaneously, habitat fragmentation can mediate species’ responses to warming. As this potential interactive effect has proven difficult to test empirically, we collected data on birds over 10 years of climate warming in a reservoir subtropical island system that was formed 65 years ago. We investigated how the mechanisms underlying climate-driven directional change in community composition were mediated by habitat fragmentation. We found thermophilization driven by increasing warm-adapted species and decreasing cold-adapted species in terms of trends in colonization rate, extinction rate, occupancy rate and population size. Critically, colonization rates of warm-adapted species increased faster temporally on smaller or less isolated islands; cold-adapted species generally were lost more quickly temporally on closer islands. This provides support for dispersal limitation and microclimate buffering as primary proxies by which habitat fragmentation mediates species range shift. Overall, this study advances our understanding of biodiversity responses to interacting global change drivers.

Article activity feed

-

-

-

-

eLife Assessment

This fundamental study substantially advances our understanding of how habitat fragmentation and climate change jointly influence bird community thermophilization in a fragmented island system. The authors provide convincing evidence using appropriate and validated methodologies to examine how island area and isolation affect the colonization of warm-adapted species and the extinction of cold-adapted species. This study is of high interest to ecologists and conservation biologists, as it provides insight into how ecosystems and communities respond to climate change.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

Juan Liu et al. investigated the interplay between habitat fragmentation and climate-driven thermophilization in birds in an island system in China. They used extensive bird monitoring data (9 surveys per year per island) across 36 islands of varying size and isolation from the mainland covering 10 years. The authors use extensive modeling frameworks to test a general increase of the occurrence and abundance of warm-dwelling species and vice versa for cold-dwelling species using the widely used Community Temperature Index (CTI), as well the relationship between island fragmentation in terms of island area and isolation from the mainland on extinction and colonization rates of cold- and warm-adapted species. They found that indeed there was thermophilization happening during the last 10 years, which …

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

Juan Liu et al. investigated the interplay between habitat fragmentation and climate-driven thermophilization in birds in an island system in China. They used extensive bird monitoring data (9 surveys per year per island) across 36 islands of varying size and isolation from the mainland covering 10 years. The authors use extensive modeling frameworks to test a general increase of the occurrence and abundance of warm-dwelling species and vice versa for cold-dwelling species using the widely used Community Temperature Index (CTI), as well the relationship between island fragmentation in terms of island area and isolation from the mainland on extinction and colonization rates of cold- and warm-adapted species. They found that indeed there was thermophilization happening during the last 10 years, which was more pronounced for the CTI based on abundances and less clearly for the occurrence based metric. Generally, the authors show that this is driven by an increased colonization rate of warm-dwelling and an increased extinction rate of cold-dwelling species. Interestingly, they unravel some of the mechanisms behind this dynamic by showing that warm-adapted species increased while cold-dwelling decreased more strongly on smaller islands, which is - according to the authors - due to lowered thermal buffering on smaller islands (which was supported by air temperature monitoring done during the study period on small and large islands). They argue, that the increased extinction rate of cold-adapted species could also be due to lowered habitat heterogeneity on smaller islands. With regards to island isolation, they show that also both thermophilization processes (increase of warm and decrease of cold-adapted species) was stronger on islands closer to the mainland, due to closer sources to species populations of either group on the mainland as compared to limited dispersal (i.e. range shift potential) in more isolated islands.

The conclusions drawn in this study are sound, and mostly well supported by the results. Only few aspects leave open questions and could quite likely be further supported by the authors themselves thanks to their apparent extensive understanding of the study system.

Strengths:

The study questions and hypotheses are very well aligned with the methods used, ranging from field surveys to extensive modeling frameworks, as well as with the conclusions drawn from the results. The study addresses a complex question on the interplay between habitat fragmentation and climate-driven thermophilization which can naturally be affected by a multitude of additional factors than the ones included here. Nevertheless, the authors use a well balanced method of simplifying this to the most important factors in question (CTI change, extinction, colonization, together with habitat fragmentation metrics of isolation and island area). The interpretation of the results presents interesting mechanisms without being too bold on their findings and by providing important links to the existing literature as well as to additional data and analyses presented in the appendix.

Weaknesses:

The metric of island isolation based on distance to the mainland seems a bit too oversimplified as in real-life the study system rather represents an island network where the islands of different sizes are in varying distances to each other, such that smaller islands can potentially draw from the species pools from near-by larger islands too - rather than just from the mainland. Although the authors do explain the reason for this metric, backed up by earlier research, a network approach could be worthwhile exploring in future research done in this system. The fact, that the authors did find a signal of island isolation does support their method, but the variation in responses to this metric could hint on a more complex pattern going on in real-life than was assumed for this study.

Comments on revisions:

I'm happy with the revisions made by the authors.

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

Juan Liu et al. investigated the interplay between habitat fragmentation and climate-driven thermophilization in birds in an island system in China. They used extensive bird monitoring data (9 surveys per year per island) across 36 islands of varying size and isolation from the mainland covering 10 years. The authors use extensive modeling frameworks to test a general increase of the occurrence and abundance of warm-dwelling species and vice versa for cold-dwelling species using the widely used Community Temperature Index (CTI), as well the relationship between island fragmentation in terms of island area and isolation from the mainland on extinction and colonization rates of cold- and warm-adapted …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

Juan Liu et al. investigated the interplay between habitat fragmentation and climate-driven thermophilization in birds in an island system in China. They used extensive bird monitoring data (9 surveys per year per island) across 36 islands of varying size and isolation from the mainland covering 10 years. The authors use extensive modeling frameworks to test a general increase of the occurrence and abundance of warm-dwelling species and vice versa for cold-dwelling species using the widely used Community Temperature Index (CTI), as well the relationship between island fragmentation in terms of island area and isolation from the mainland on extinction and colonization rates of cold- and warm-adapted species. They found that indeed there was thermophilization happening during the last 10 years, which was more pronounced for the CTI based on abundances and less clearly for the occurrence based metric. Generally, the authors show that this is driven by an increased colonization rate of warm-dwelling and an increased extinction rate of cold-dwelling species. Interestingly, they unravel some of the mechanisms behind this dynamic by showing that warm-adapted species increased while cold-dwelling decreased more strongly on smaller islands, which is - according to the authors - due to lowered thermal buffering on smaller islands (which was supported by air temperature monitoring done during the study period on small and large islands). They argue, that the increased extinction rate of cold-adapted species could also be due to lowered habitat heterogeneity on smaller islands. With regards to island isolation, they show that also both thermophilization processes (increase of warm and decrease of cold-adapted species) was stronger on islands closer to the mainland, due to closer sources to species populations of either group on the mainland as compared to limited dispersal (i.e. range shift potential) in more isolated islands.

The conclusions drawn in this study are sound, and mostly well supported by the results. Only few aspects leave open questions and could quite likely be further supported by the authors themselves thanks to their apparent extensive understanding of the study system.

Strengths:

The study questions and hypotheses are very well aligned with the methods used, ranging from field surveys to extensive modeling frameworks, as well as with the conclusions drawn from the results. The study addresses a complex question on the interplay between habitat fragmentation and climate-driven thermophilization which can naturally be affected by a multitude of additional factors than the ones included here. Nevertheless, the authors use a well balanced method of simplifying this to the most important factors in question (CTI change, extinction, colonization, together with habitat fragmentation metrics of isolation and island area). The interpretation of the results presents interesting mechanisms without being too bold on their findings and by providing important links to the existing literature as well as to additional data and analyses presented in the appendix.

Weaknesses:

The metric of island isolation based on distance to the mainland seems a bit too oversimplified as in real-life the study system rather represents an island network where the islands of different sizes are in varying distances to each other, such that smaller islands can potentially draw from the species pools from near-by larger islands too - rather than just from the mainland. Although the authors do explain the reason for this metric, backed up by earlier research, a network approach could be worthwhile exploring in future research done in this system. The fact, that the authors did find a signal of island isolation does support their method, but the variation in responses to this metric could hint on a more complex pattern going on in real-life than was assumed for this study.

Thank you again for this suggestion. Based on the previous revision, we discussed more about the importance of taking the island network into future research. The paragraph is now on Lines 294-304:

“As a caveat, we only consider the distance to the nearest mainland as a measure of fragmentation, consistent with previous work in this system (Si et al., 2014), but we acknowledge that other distance-based metrics of isolation that incorporate inter-island connections and island size could hint on a more complex pattern going on in real-life than was assumed for this study, thus reveal additional insights on fragmentation effects. For instance, smaller islands may also potentially utilize species pools from nearby larger islands, rather than being limited solely to those from the mainland. The spatial arrangement of islands, like the arrangement of habitat, can influence niche tracking of species (Fourcade et al., 2021). Future studies should use a network approach to take these metrics into account to thoroughly understand the influence of isolation and spatial arrangement of patches in mediating the effect of climate warming on species.”

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations for the authors):

Great job on the revision! The new version reads well and in my opinion all comments were addressed appropriately. A few additional comments are as follows:

Thank you very much for your further review and recognition. We have carefully modified the manuscript according to all recommendations.

(1) L 62: replace shifts with process

Done. We also added the word “transforming” to match this revision. The new sentence is now on Lines 61-63:

“Habitat fragmentation, usually defined as the process of transforming continuous habitat into spatially isolated and small patches”

(2) L 363: Your metric for habitat fragmentation is isolation and habitat area and I think this could be introduced already in the introduction, where you somewhat define fragmentation (although it could be clearer still). You could also discuss this in the discussion more, that other measures of fragmentation may be interesting to look at.

Thank you for this suggestion. We now introduced metric of habitat fragmentation in the Introduction part after habitat fragmentation was defined. The sentence is now on Lines 64-66:

“Among the various ways in which habitat fragmentation is conceptualized and measured, patch area and isolation are two of the most used measures (Fahrig, 2003).”

(3) L 384: replace for with because of

Done.

(4) L 388: "Following this filtering, 60 ...."

Done.

(5) Figure 1: In panels b-d you use different terms (fragmented, small, isolated) but aiming to describe the same thing. I would highly recommend to either use fragmented islands or isolated islands for all panels. Although I see that in your study fragmentation includes both, habitat loss and isolation. So make this clear in the figure caption too...

Thank you very much for this suggestion. It’s important to maintain consistency in using “fragmentation”. We change “fragmented, small, isolated” into “Fragmented patches” in the caption of b-d. The modified caption is now on Line 771:

(6) L 783: replace background with habitat (or landscape) and exhibit with exemplify

Done. The new sentence is now on Lines 782-784:

“The three distinct patches signify a fragmented landscape and the community in the middle of the three patches was selected to exemplify colonization-extinction dynamics in fragmented habitats.”

(7) One bigger thing is the definition of fragmentation in your study for which you used habitat area (from habitat loss process) and isolation. This could still be clarified a bit more, especially in the figures. In Fig. 1 the smaller panels b-d could all be titled fragmented islands as this is what the different terms describe in your study (small, isolated) and thus the figure would become even clearer. Otherwise I'm happy with the changes made.

Thank you for raising this important question. Yes, “habitat fragmentation” in our research includes both habitat loss and fragmentation per se. We have clarified the caption of b-d in Figure 1 as suggested by Recommendation (5). We believe this can make it clearer to the readers.

-

-

eLife Assessment

This fundamental study substantially advances our understanding of how habitat fragmentation and climate change jointly influence bird community thermophilization in a fragmented island system. The authors provide convincing evidence using appropriate and validated methodologies to examine how island area and isolation affect the colonization of warm-adapted species and the extinction of cold-adapted species. While minor clarifications regarding the definition of fragmentation could further enhance the presentation, the study is of high interest to ecologists and conservation biologists, as it provides insight into how ecosystems and communities respond to climate change.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

Juan Liu et al. investigated the interplay between habitat fragmentation and climate-driven thermophilization in birds in an island system in China. They used extensive bird monitoring data (9 surveys per year per island) across 36 islands of varying size and isolation from the mainland covering 10 years. The authors use extensive modeling frameworks to test a general increase of the occurrence and abundance of warm-dwelling species and vice versa for cold-dwelling species using the widely used Community Temperature Index (CTI), as well the relationship between island fragmentation in terms of island area and isolation from the mainland on extinction and colonization rates of cold- and warm-adapted species. They found that indeed there was thermophilization happening during the last 10 years, which …

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

Juan Liu et al. investigated the interplay between habitat fragmentation and climate-driven thermophilization in birds in an island system in China. They used extensive bird monitoring data (9 surveys per year per island) across 36 islands of varying size and isolation from the mainland covering 10 years. The authors use extensive modeling frameworks to test a general increase of the occurrence and abundance of warm-dwelling species and vice versa for cold-dwelling species using the widely used Community Temperature Index (CTI), as well the relationship between island fragmentation in terms of island area and isolation from the mainland on extinction and colonization rates of cold- and warm-adapted species. They found that indeed there was thermophilization happening during the last 10 years, which was more pronounced for the CTI based on abundances and less clearly for the occurrence based metric. Generally, the authors show that this is driven by an increased colonization rate of warm-dwelling and an increased extinction rate of cold-dwelling species. Interestingly, they unravel some of the mechanisms behind this dynamic by showing that warm-adapted species increased while cold-dwelling decreased more strongly on smaller islands, which is - according to the authors - due to lowered thermal buffering on smaller islands (which was supported by air temperature monitoring done during the study period on small and large islands). They argue, that the increased extinction rate of cold-adapted species could also be due to lowered habitat heterogeneity on smaller islands. With regards to island isolation, they show that also both thermophilization processes (increase of warm and decrease of cold-adapted species) was stronger on islands closer to the mainland, due to closer sources to species populations of either group on the mainland as compared to limited dispersal (i.e. range shift potential) in more isolated islands.

The conclusions drawn in this study are sound, and mostly well supported by the results. Only few aspects leave open questions and could quite likely be further supported by the authors themselves thanks to their apparent extensive understanding of the study system.

Strengths:

The study questions and hypotheses are very well aligned with the methods used, ranging from field surveys to extensive modeling frameworks, as well as with the conclusions drawn from the results. The study addresses a complex question on the interplay between habitat fragmentation and climate-driven thermophilization which can naturally be affected by a multitude of additional factors than the ones included here. Nevertheless, the authors use a well balanced method of simplifying this to the most important factors in question (CTI change, extinction, colonization, together with habitat fragmentation metrics of isolation and island area). The interpretation of the results presents interesting mechanisms without being too bold on their findings and by providing important links to the existing literature as well as to additional data and analyses presented in the appendix.

Weaknesses:

The metric of island isolation based on distance to the mainland seems a bit too oversimplified as in real-life the study system rather represents an island network where the islands of different sizes are in varying distances to each other, such that smaller islands can potentially draw from the species pools from near-by larger islands too - rather than just from the mainland. Although the authors do explain the reason for this metric, backed up by earlier research, a network approach could be worthwhile exploring in future research done in this system. The fact, that the authors did find a signal of island isolation does support their method, but the variation in responses to this metric could hint on a more complex pattern going on in real-life than was assumed for this study.

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

We summarized the main changes:

(1) In the Introduction part, we give a general definition of habitat fragmentation to avoid confusion, as reviewers #1 and #2 suggested.

(2) We clarify the two aspects of the observed “extinction”——“true dieback” and “emigration”, as reviewers #2 and #3 suggested.

(3) In the Methods part, we 1) clarify the reason for testing the temporal trend in colonization/extinction dynamics and describe how to select islands as reviewer #1 suggested; 2) describe how to exclude birds from the analysis as reviewer #2 suggested.

(4) In the Results part, we modified and rearranged Figure 4-6 as reviewers #1, #2 and #3 suggested.

(5) In the Discussion part, we 1) discuss the multiple aspects of the metric of isolation for future research as …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

We summarized the main changes:

(1) In the Introduction part, we give a general definition of habitat fragmentation to avoid confusion, as reviewers #1 and #2 suggested.

(2) We clarify the two aspects of the observed “extinction”——“true dieback” and “emigration”, as reviewers #2 and #3 suggested.

(3) In the Methods part, we 1) clarify the reason for testing the temporal trend in colonization/extinction dynamics and describe how to select islands as reviewer #1 suggested; 2) describe how to exclude birds from the analysis as reviewer #2 suggested.

(4) In the Results part, we modified and rearranged Figure 4-6 as reviewers #1, #2 and #3 suggested.

(5) In the Discussion part, we 1) discuss the multiple aspects of the metric of isolation for future research as reviewer #3 suggested; 2) provide concrete evidence about the relationship between habitat diversity or heterogeneity and island area and 3) provide a wider perspective about how our results can inform conservation practices in fragmented habitats as reviewer #2 suggested.

eLife Assessment

This important study enhances our understanding of how habitat fragmentation and climate change jointly influence bird community thermophilization in a fragmented island system. The evidence supporting some conclusions is incomplete, as while the overall trends are convincing, some methodological aspects, particularly the isolation metrics and interpretation of colonization/extinction rates, require further clarification. This work will be of broad interest to ecologists and conservation biologists, providing crucial insights into how ecosystems and communities react to climate change.

We sincerely extend our gratitude to you and the esteemed reviewers for acknowledging the importance of our study and for raising these concerns. We have clarified the rationale behind our analysis of temporal trends in colonization and extinction dynamics, as well as the choice of distance to the mainland as the isolation metric. Additionally, we further discuss the multiple aspects of the metric of isolation for future research and provide concrete supporting evidence about the relationship between habitat diversity or heterogeneity and island area.

Incorporating these valuable suggestions, we have thoroughly revised our manuscript, ensuring that it now presents a more comprehensive and nuanced account of our research. We are confident that these improvements will further enhance the impact and relevance of our work for ecologists and conservation biologists alike, offering vital insights into the resilience and adaptation strategies of communities facing the challenges of climate change.

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Summary:

This study reports on the thermophilization of bird communities in a network of islands with varying areas and isolation in China. Using data from 10 years of transect surveys, the authors show that warm-adapted species tend to gradually replace cold-adapted species, both in terms of abundance and occurrence. The observed trends in colonisations and extinctions are related to the respective area and isolation of islands, showing an effect of fragmentation on the process of thermophilization.

Strengths:

Although thermophilization of bird communities has been already reported in different contexts, it is rare that this process can be related to habitat fragmentation, despite the fact that it has been hypothesized for a long time that it could play an important role. This is made possible thanks to a really nice study system in which the construction of a dam has created this incredible Thousand Islands lake. Here, authors do not simply take observed presence-absence as granted and instead develop an ambitious hierarchical dynamic multi-species occupancy model. Moreover, they carefully interpret their results in light of their knowledge of the ecology of the species involved.

Response: We greatly appreciate your recognition of our study system and the comprehensive approach and careful interpretation of results.

Weaknesses:

Despite the clarity of this paper on many aspects, I see a strong weakness in the authors' hypotheses, which obscures the interpretation of their results. Looking at Figure 1, and in many sentences of the text, a strong baseline hypothesis is that thermophilization occurs because of an increasing colonisation rate of warm-adapted species and extinction rate of cold-adapted species. However, there does not need to be a temporal trend! Any warm-adapted species that colonizes a site has a positive net effect on CTI; similarly, any cold-adapted species that goes extinct contributes to thermophilization.

Thank you very much for these thoughtful comments. The understanding depends on the time frame of the study and specifically, whether the system is at equilibrium. We think your claim is based on this background: if the system is not at equilibrium, then CTI can shift simply by having differential colonization (or extinction) rates for warm-adapted versus cold-adapted species. We agree with you in this case.

On the other hand, if a community is at equilibrium, then there will be no net change in CTI over time. Imagine we have an archipelago where the average colonization of warm-adapted species is larger than the average colonization of cold-adapted species, then over time the archipelago will reach an equilibrium with stable colonization/extinction dynamics where the average CTI is stable over time. Once it is stable, then if there is a temporal trend in colonization rates, the CTI will change until a new equilibrium is reached (if it is reached).

For our system, the question then is whether we can assume that the system is or has ever been at equilibrium. If it is not at equilibrium, then CTI can shift simply by having differential colonization (or extinction) rates for warm-adapted versus cold-adapted species. If the system is at equilibrium (at the beginning of the study), then CTI will only shift if there is a temporal change or trend in colonization or extinction rates.

Habitat fragmentation can affect biomes for decades after dam formation. The “Relaxation effect” (Gonzalez, 2000) refers to the fact that the continent acts as a potential species pool for island communities. Under relaxation, some species will be filtered out over time, mainly through the selective extinction of species that are highly sensitive to fragmentation. Meanwhile, for a 100-hectare patch, it takes about ten years to lose 50% of bird species; The smaller the patch area, the shorter the time required (Ferraz et al., 2003; Haddad et al., 2015). This study was conducted 50 to 60 years after the formation of the TIL, making the system with a high probability of reaching “equilibrium” through “Relaxation effect”(Si et al., 2014). We have no way of knowing exactly whether “equilibrium” is true in our system. Thus, changing rates of colonization-extinction over time is actually a much stronger test of thermophilization, which makes our inference more robust.

We add a note to the legend of Figure 1 on Lines 781-786:

“CTI can also change simply due to differential colonization-extinction rates by thermal affinity if the system is not at equilibrium prior to the study. In our study system, we have no way of knowing whether our island system was at equilibrium at onset of the study, thus, focusing on changing rates of colonization-extinction over time presents a much stronger tests of thermophilization.”

We hope this statement can make it clear. Thank you again for this meaningful question.

Another potential weakness is that fragmentation is not clearly defined. Generally, fragmentation sensu lato involves both loss of habitat area and changes in the spatial structure of habitats (i.e. fragmentation per se). Here, both area and isolation are considered, which may be slightly confusing for the readers if not properly defined.

Thank you for reminding us of that. Habitat fragmentation in this study involves both habitat loss and fragmentation per se. We have clarified the general definition in the Introduction on Lines 61-63:

“Habitat fragmentation, usually defined as the shifts of continuous habitat into spatially isolated and small patches (Fahrig, 2003), in particular, has been hypothesized to have interactive effects with climate change on community dynamics.”

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Summary:

This study addresses whether bird community reassembly in time is related to climate change by modelling a widely used metric, the community temperature index (CTI). The authors first computed the temperature index of 60 breeding bird species thanks to distribution atlases and climatic maps, thus obtaining a measure of the species realized thermal niche.

These indices were aggregated at the community level, using 53 survey transects of 36 islands (repeated for 10 years) of the Thousand Islands Lake, eastern China. Any increment of this CTI (i.e. thermophilization) can thus be interpreted as a community reassembly caused by a change in climate conditions (given no confounding correlations).

The authors show thanks to a mix of Bayesian and frequentist mixed effect models to study an increment of CTI at the island level, driven by both extinction (or emigration) of cold-adapted species and colonization of newly adapted warm-adapted species. Less isolated islands displayed higher colonization and extinction rates, confirming that dispersal constraints (created by habitat fragmentation per se) on colonization and emigration are the main determinants of thermophilization. The authors also had the opportunity to test for habitat amount (here island size). They show that the lack of microclimatic buffering resulting from less forest amount (a claim backed by understory temperature data) exacerbated the rates of cold-adapted species extinction while fostering the establishment of warm-adapted species.

Overall these findings are important to range studies as they reveal the local change in affinity to the climate of species comprising communities while showing that the habitat fragmentation VS amount distinction is relevant when studying thermophilization. As is, the manuscript lacks a wider perspective about how these results can be fed into conservation biology, but would greatly benefit from it. Indeed, this study shows that in a fragmented reserve context, habitat amount is very important in explaining trends of loss of cold-adapted species, hinting that it may be strategic to prioritize large habitats to conserve such species. Areas of diverse size may act as stepping stones for species shifting range due to climate change, with small islands fostering the establishment of newly adapted warm-adapted species while large islands act as refugia for cold-adapted species. This study also shows that the removal of dispersal constraints with low isolation may help species relocate to the best suitable microclimate in a heterogenous reserve context.

Thank you very much for your valuable feedback. We greatly appreciate your recognition of the scientific question to the extensive dataset and diverse approach. In particular, you provided constructive suggestions and examples on how to extend the results to conservation guidance. This is something we can’t ignore in the manuscript. We have added a paragraph to the end of the Discussion, stating how our results can inform conservation, on Lines 339-347:

‘Overall, our findings have important implications for conservation practices. Firstly, we confirmed the role of isolation in limiting range shifting. Better connected landscapes should be developed to remove dispersal constraints and facilitate species’ relocation to the best suitable microclimate. Second, small patches can foster the establishment of newly adapted warm-adapted species while large patches can act as refugia for cold-adapted species. Therefore, preserving patches of diverse sizes can act as stepping stones or shelters in a warming climate depending on the thermal affinity of species. These insights are important supplement to the previous emphasis on the role of habitat diversity in fostering (Richard et al., 2021) or reducing (Gaüzère et al., 2017) community-level climate debt.’

Strength:

The strength of the study lies in its impressive dataset of bird resurveys, that cover 10 years of continued warming (as evidenced by weather data), 60 species in 36 islands of varying size and isolation, perfect for disentangling habitat fragmentation and habitat amount effects on communities. This distinction allows us to test very different processes mediating thermophilization; island area, linked to microclimatic buffering, explained rates for a variety of species. Dispersal constraints due to fragmentation were harder to detect but confirms that fragmentation does slow down thermophilization processes.

This study is a very good example of how the expected range shift at the biome scale of the species materializes in small fragmented regions. Specifically, the regional dynamics the authors show are analogous to what processes are expected at the trailing and colonizing edge of a shifting range: warmer and more connected places display the fastest turnover rates of community reassembly. The authors also successfully estimated extinction and colonization rates, allowing a more mechanistic understanding of CTI increment, being the product of two processes.

The authors showed that regional diversity and CTI computed only by occurrences do not respond in 10 years of warming, but that finer metrics (abundance-based, or individual islands considered) do respond. This highlights the need to consider a variety of case-specific metrics to address local or regional trends. Figure Appendix 2 is a much-appreciated visualization of the effect of different data sources on Species thermal Index (STI) calculation.

The methods are long and diverse, but they are documented enough so that an experienced user with the use of the provided R script can follow and reproduce them.

Thank you very much for your profound Public Review. We greatly appreciate your recognition of the scientific question, the extensive dataset and the diverse approach.

Weaknesses:

While the overall message of the paper is supported by data, the claims are not uniformly backed by the analysis. The trends of island-specific thermophilization are very credible (Figure 3), however, the variable nature of bird observations (partly compensated by an impressive number of resurveys) propagate a lot of errors in the estimation of species-specific trends in occupancy, abundance change, and the extinction and colonization rates. This materializes into a weak relationship between STI and their respective occupancy and abundance change trends (Figure 4a, Figure 5, respectively), showing that species do not uniformly contribute to the trend observed in Figure 3. This is further shown by the results presented in Figure 6, which present in my opinion the topical finding of the study. While a lot of species rates response to island areas are significant, the isolation effect on colonization and extinction rates can only be interpreted as a trend as only a few species have a significant effect. The actual effect on the occupancy change rates of species is hard to grasp, and this trend has a potentially low magnitude (see below).

Thank you very much for pointing out this shortcoming. The R2 between STI and their respective occupancy trends is relatively small (R2=0.035). But the R2 between STI and their respective abundance change trends are relatively bigger, in the context of Ecology research (R2=0.123). The R2 between STI and their respective colonization rate (R2=0.083) and extinction rate trends (R2=0.053) are also relatively small. Low R2 indicates that we can’t make predictions using the current model, we must notice that except STI, other factors may influence the species-specific occupancy trend. Nonetheless, it is important to notice that the standardized coefficient estimates are not minor and the trend is also significant, indicating the species-specific response is as least related to STI.

The number of species that have significant interaction terms for isolation (Figure 6) is indeed low. Although there is uncertainty in the estimation of relationships, there are also consistent trends in response to habitat fragmentation of colonization of warm-adapted species and extinction of cold-adapted species. This is especially true for the effect of isolation, where on islands nearer to the mainland, warm-adapted species (15 out of 15 investigated species) increased their colonization probability at a higher rate over time, while most cold-adapted species (21 out of 23 species) increased their extinction probability at a higher rate. We now better highlight these results in the Results and Discussion.

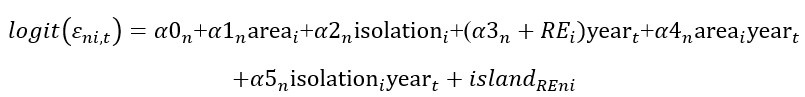

While being well documented, the myriad of statistical methods used by the authors ampere the interpretation of the figure as the posterior mean presented in Figure 4b and Figure 6 needs to be transformed again by a logit-1 and fed into the equation of the respective model to make sense of. I suggest a rewording of the caption to limit its dependence on the method section for interpretation.

Thank you for this suggestion. The value on the Y axis indicates the posterior mean of each variable (year, area, isolation and their interaction effects) extracted from the MSOM model, where the logit(extinction rate) or logit(colonization rate) was the response variable. All variables were standardized before analysis to make them comparable so interpretation is actually quite straight forward: positive values indicate positive influence while negative values indicate negative influence. Because the goal of Figure 6 is to display the negative/positive effect, we didn’t back-transform them. Following your advice, we thus modified the caption of Figure 6 (now renumbered as Figure 5, following a comment from Reviewer #3, to move Figure 5 to Figure 4c). The modified title and legends of Figure 5 are on Lines 817-820:

“Figure 5. Posterior estimates of logit-scale parameters related to cold-adapted species’ extinction rates and warm-adapted species’ colonization rates. Points are species-specific posterior means on the logit-scale, where parameters >0 indicate positive effects (on extinction [a] or colonization [b]) and parameters <0 indicate negative effects...”

By using a broad estimate of the realized thermal niche, a common weakness of thermophilization studies is the inability to capture local adaptation in species' physiological or behavioral response to a rise in temperature. The authors however acknowledge this limitation and provide specific examples of how species ought to evade high temperatures in this study region.

We appreciate your recognition. This is a common problem in STI studies. We hope in future studies, researchers can take more details about microclimate of species’ true habitat across regions into consideration when calculating STI. Although challenging, focusing on a smaller portion of its distribution range may facilitate achievement.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Summary:

Juan Liu et al. investigated the interplay between habitat fragmentation and climate-driven thermophilization in birds in an island system in China. They used extensive bird monitoring data (9 surveys per year per island) across 36 islands of varying size and isolation from the mainland covering 10 years. The authors use extensive modeling frameworks to test a general increase in the occurrence and abundance of warm-dwelling species and vice versa for cold-dwelling species using the widely used Community Temperature Index (CTI), as well as the relationship between island fragmentation in terms of island area and isolation from the mainland on extinction and colonization rates of cold- and warm-adapted species. They found that indeed there was thermophilization happening during the last 10 years, which was more pronounced for the CTI based on abundances and less clearly for the occurrence-based metric. Generally, the authors show that this is driven by an increased colonization rate of warm-dwelling and an increased extinction rate of cold-dwelling species. Interestingly, they unravel some of the mechanisms behind this dynamic by showing that warm-adapted species increased while cold-dwelling decreased more strongly on smaller islands, which is - according to the authors - due to lowered thermal buffering on smaller islands (which was supported by air temperature monitoring done during the study period on small and large islands). They argue, that the increased extinction rate of cold-adapted species could also be due to lowered habitat heterogeneity on smaller islands. With regards to island isolation, they show that also both thermophilization processes (increase of warm and decrease of cold-adapted species) were stronger on islands closer to the mainland, due to closer sources to species populations of either group on the mainland as compared to limited dispersal (i.e. range shift potential) in more isolated islands.

The conclusions drawn in this study are sound, and mostly well supported by the results. Only a few aspects leave open questions and could quite likely be further supported by the authors themselves thanks to their apparent extensive understanding of the study system.

Strengths:

The study questions and hypotheses are very well aligned with the methods used, ranging from field surveys to extensive modeling frameworks, as well as with the conclusions drawn from the results. The study addresses a complex question on the interplay between habitat fragmentation and climate-driven thermophilization which can naturally be affected by a multitude of additional factors than the ones included here. Nevertheless, the authors use a well-balanced method of simplifying this to the most important factors in question (CTI change, extinction, and colonization, together with habitat fragmentation metrics of isolation and island area). The interpretation of the results presents interesting mechanisms without being too bold on their findings and by providing important links to the existing literature as well as to additional data and analyses presented in the appendix.

We appreciate very much for your positive and constructive comments and suggestions. Thank you for your recognition of the scientific question, the modeling approach and the conclusions.

Weaknesses:

The metric of island isolation based on the distance to the mainland seems a bit too oversimplified as in real life the study system rather represents an island network where the islands of different sizes are in varying distances to each other, such that smaller islands can potentially draw from the species pools from near-by larger islands too - rather than just from the mainland. Thus a more holistic network metric of isolation could have been applied or at least discussed for future research. The fact, that the authors did find a signal of island isolation does support their method, but the variation in responses to this metric could hint at a more complex pattern going on in real-life than was assumed for this study.

Thank you for this meaningful question. Isolation can be measured in different ways in the study region. We chose the distance to the mainland as a measure of isolation based on the results of a previous study. One study in our system provided evidence that the colonization rate and extinction rate of breeding bird species were best fitted using distance to the nearest mainland over other distance-based measures (distance to the nearest landmass, distance to the nearest bigger landmass)(Si et al., 2014). Besides, their results produced almost identical patterns of the relationship between isolation and colonization/extinction rate (Si et al., 2014). That’s why we only selected “Distance to the mainland” in our current analysis and we do find some consistent patterns as expected. The plants on all islands were cleared out about 60 years ago due to dam construction, with all bird species coming from the mainland as the original species pool through a process called “relaxation”. This could be the reason why distance to the nearest mainland is the best predictor.

We agree with you that it’s still necessary to consider more aspects of “isolation” at least in discussion for future research. In our Discussion, we address these on Lines 292-299:

“As a caveat, we only consider the distance to the nearest mainland as a measure of fragmentation, consistent with previous work in this system (Si et al., 2014), but we acknowledge that other distance-based metrics of isolation that incorporate inter-island connections could reveal additional insights on fragmentation effects. The spatial arrangement of islands, like the arrangement of habitat, can influence niche tracking of species (Fourcade et al., 2021). Future studies should take these metrics into account to thoroughly understand the influence of isolation and spatial arrangement of patches in mediating the effect of climate warming on species.”

Further, the link between larger areas and higher habitat diversity or heterogeneity could be presented by providing evidence for this relationship. The authors do make a reference to a paper done in the same study system, but a more thorough presentation of it would strengthen this assumption further.

Thank you very much for this question. We now add more details about the relationship between habitat diversity and heterogeneity based on a related study in the same system. The observed number of species significantly increased with increasing island area (slope = 4.42, R2 = 0.70, p < .001), as did the rarefied species richness per island (slope = 1.03, R2 = 0.43, p < .001), species density (slope = 0.80, R2 = 0.33, p = .001) and the rarefied species richness per unit area (slope = 0.321, R2 = 0.32, p = .001). We added this supporting evidence on Lines 317-321:

“We thus suppose that habitat heterogeneity could also mitigate the loss of these relatively cold-adapted species as expected. Habitat diversity, including the observed number of species, the rarefied species richness per island, species density and the rarefied species richness per unit area, all increased significantly with island area instead of isolation in our system (Liu et al., 2020)”

Despite the general clear patterns found in the paper, there were some idiosyncratic responses. Those could be due to a multitude of factors which could be discussed a bit better to inform future research using a similar study design.

Thank you for these suggestions. We added a summary statement about the reasons for idiosyncratic responses on Lines 334-338:

“Overall, these idiosyncratic responses reveal several possible mechanisms in regulating species' climate responses, including resource demands and biological interactions like competition and predation. Future studies are needed to take these factors into account to understand the complex mechanisms by which habitat loss meditates species range shifts.”

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations For The Authors):

(1) Figure 1: I disagree that there should be a temporal trend in colonisation/extinction dynamics.

Thank you again for these thoughtful comments. We have explained in detail in the response to the Public Review.

(2) L 485-487: As explained before I disagree. I don't see why there needs to be a temporal trend in colonization and extinction.

Thank you again for these thoughtful comments. Because we can’t guarantee that the study system has reached equilibrium, changing rates of colonization-extinction over time is actually a much stronger test of thermophilization. More detailed statement can be seen in the response to the Public Review.

(3) L 141: which species' ecological traits?

Sorry for the confusion. The traits included continuous variables (dispersal ability, body size, body mass and clutch size) and categorical variables (diet, active layer, residence type). Specifically, we tested the correlation between STI and dispersal ability, body size, body mass and clutch size using Pearson correlation test. We also tested the difference in STI between different trait groups using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for three Category variables: diet (carnivorous/ omnivorous/ herbivory), active layer (canopy/mid/low), and residence type (resident species/summer visitor). There is no significant difference between any two groups for each of the three category variables (p > 0.2). We added these on Lines 141-145:

“No significant correlation was found between STI and species’ ecological traits; specifically, the continuous variables of dispersal ability, body size, body mass and clutch size (Pearson correlations for each, |r| < 0.22), and the categorial variables of diet (carnivorous/omnivorous/herbivory), active layer (canopy/mid/low), and residence type (resident species/summer visitor)”

(4) L 143: CTIoccur and CTIabun were not defined before.

Because CTIoccur and CTIabun were first defined in Methods part (section 4.4), we change the sentence to a more general statement here on Lines 147-150:

“At the landscape scale, considering species detected across the study area, occurrence-based CTI (CTIoccur; see section 4.4) showed no trend (posterior mean temporal trend = 0.414; 95% CrI: -12.751, 13.554) but abundance-based CTI (CTIabun; see section 4.4) showed a significant increasing trend.”

(5) Figure 4: what is the dashed vertical line? I assume the mean STI across species?

Sorry for the unclear description. The vertical dashed line indicates the median value of STI for 60 species, as a separation of warm-adapted species and cold-adapted species. We have added these details on Lines 807-809:

“The dotted vertical line indicates the median of STI values. Cold-adapted species are plotted in blue and warm-adapted species are plotted in orange.”

(6) Figure 6: in the legend, replace 'points in blue' with 'points in blue/orange' or 'solid dots' or something similar.

Thank you for this suggestion. We changed it to “points in blue/orange” on Lines 823.

(7) L 176-176: unclear why the interaction parameters are particularly important for explaining the thermophilization mechanism: if e.g. colonization rate of warm-adapted species is constantly higher in less isolated islands, (and always higher than the extinction rate of the same species), it means that thermophilization is increased in less isolated islands, right?

Thank you for this question. This is also related to the question about “Why use temporal trends in colonization/extinction rate to test for thermophilization mechanisms”. Colonization-extinction over time is actually a much stronger test of thermophilization (more details refer to response to Public Review and Recommendations 1&2).

Based on this, the two main driving processes of thermophilization mechanism include the increasing colonization rate of warm-adapted species and the increasing extinction rate of cold-adapted species with year. The interaction effect between island area (or isolation) and year on colonization rate (or extinction rate) can tell us how habitat fragmentation mediates the year effect. For example, if the interaction term between year and isolation is negative for a warm-adapted species that increased in colonization rate with year, it indicates that the colonization rate increased faster on less isolated islands. This is a signal of a faster thermophilization rate on less-isolated islands.

(8) L201-203: this is only little supported by the results that actually show that there is NO significant interaction for most species.

Thank you for this comment. Although most species showed non-significant interaction effect, the overall trend is relatively consistent, this is especially true for the effect of isolation. To emphasize the “trend” instead of “significant effect”, we slightly modified this sentence in more rigorous wording on Lines 205-208:

“We further found that habitat fragmentation influences two processes of thermophilization: colonization rates of most warm-adapted species tended to increase faster on smaller and less isolated islands, while the loss rates of most cold-adapted species tended to be exacerbated on less isolated islands.”

(9) Section 2.3: can't you have a population-level estimate? I struggled a bit to understand all the parameters of the MSOM (because of my lack of statistical/mathematical proficiency) so I cannot provide more advice here.

Thank you for raising this advice. We think what you are mentioning is the overall estimate across all species for each variable. From MSOM, we can get a standardized estimate of every variable (year, area, isolation, interaction) for each species, separately. Because the divergent or consistent responses among species are what we are interested in, we didn’t calculate further to get a population-level estimate.

(10) L 291: a dot is missing.

Done. Thank you for your correction.

(11) L 305, 315: a space is missing

Done

(12) L 332: how were these islands selected?

Thank you for this question. The 36 islands were selected according to a gradient of island area and isolation, spreading across the whole lake region. The selected islands guaranteed there is no significant correlation between island area and isolation (the Pearson correlation coefficient r = -0.21, p = 0.21). The biggest 7 islands among the 36 islands are also the only several islands larger than 30 ha in the whole lake region. We have modified this in the Method part on Lines 360-363.

“We selected 36 islands according to a gradient of island area and isolation with a guarantee of no significant correlation between island area and isolation (Pearson r = -0.21, p = 0.21). For each island, we calculated island area and isolation (measured in the nearest Euclidean distance to the mainland) to represent the degree of habitat fragmentation.”

(13) L 334: "Distance to the mainland" was used as a metric of isolation, but elsewhere in the text you argue that the observed thermophilization is due to interisland movements. It sounds contradictory. Why not include the average or shortest distance to the other islands?

Thank you very much for raising this comment. Yes, “Distance to the mainland” was the only metric we used for isolation. We carefully checked through the manuscript where the “interisland movement” comes from and induces the misunderstanding. It must come from Discussion 3.1 (n Lines 217-221): “Notably, when tested on the landscape scale (versus on individual island communities), only the abundance-based thermophilization trend was significant, indicating thermophilization of bird communities was mostly due to inter-island occurrence dynamics, rather than exogenous community turnover.”

Sorry, the word “inter-island” is not exactly what we want to express here, we wanted to express that “the thermophilization was mostly due to occurrence dynamics within the region, rather than exogenous community turnover outside the region”. We have changed the sentence in Discussion part on Lines 217-221:

“Notably, when tested on the landscape scale (versus on individual island communities), only the abundance-based thermophilization trend was significant, indicating thermophilization of bird communities was mostly due to occurrence dynamics within the region, rather than exogenous community turnover outside the region.”

Besides, I would like to explain why we use distance to the mainland. We chose the distance to the mainland as a measure of isolation based on the results of a previous study. One study in our system provided evidence that the colonization rate and extinction rate of breeding bird species were best fitted using distance to the nearest mainland over other distance-based measures (distance to the nearest landmass, distance to the nearest bigger landmass)(Si et al., 2014). Besides, their results produced almost identical patterns of the relationship between isolation and colonization/extinction rate(Si et al., 2014). That’s why we only selected “Distance to the mainland” in our current analysis and we do find some consistent patterns as expected. The plants on all islands were cleared out about 60 years ago due to dam construction, with all bird species coming from the mainland as the original species pool through a process called “relaxation”. This may be the reason why distance to the nearest mainland is the best predictor.

In Discussion part, we added the following discussion and talked about the other measures on Lines 292-299:

“As a caveat, we only consider the distance to the nearest mainland as a measure of fragmentation, consistent with previous work in this system (Si et al., 2014), but we acknowledge that other distance-based metrics of isolation that incorporate inter-island connections could reveal additional insights on fragmentation effects. The spatial arrangement of islands, like the arrangement of habitat, can influence niche tracking of species (Fourcade et al., 2021). Future studies should take these metrics into account to thoroughly understand the influence of isolation and spatial arrangement of patches in mediating the effect of climate warming on species.”

(14) L 347: you write 'relative' abundance but this measure is not relative to anything. Better write something like "we based our abundance estimate on the maximum number of individuals recorded across the nine annual surveys".

Thank you for this suggestion, we have changed the sentence on Lines 377-379:

“We based our abundance estimate on the maximum number of individuals recorded across the nine annual surveys.”

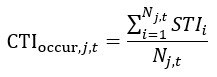

(15) L 378: shouldn't the formula for CTIoccur be (equation in latex format):

CTI{occur, j, t} =\frac{\sum_{i=1}^{N_{j,t}}STI_{i}}{N_{j,t}}

Where Nj,t is the total number of species surveyed in the community j in year t

Thank you very much for this careful check, we have revised it on Lines 415, 417:

“where Nj,t is the total number of species surveyed in the community j in year t.”

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations For The Authors):

(1) Line 76: "weakly"

Done. Thank you for your correction.

(2) Line 98: I suggest a change to this sentence: "For example, habitat fragmentation renders habitats to be too isolated to be colonized, causing sedentary butterflies to lag more behind climate warming in Britain than mobile ones"

Thank you for this modification, we have changed it on Lines 99-101.

(3) Line 101: remove either "higher" or "increasing"

Done, we have removed “higher”. Thank you for this advice.

(4) Line 102: "benefiting from near source of"

Done.

(5) Line 104: "emigrate"

Done.

(6) Introduction: I suggest making it more explicit what process you describe under the word "extinction". At first read, I thought you were only referring to the dieback of individuals, but you also included emigration as an extinction process. It also needs to be reworded in Fig 1 caption.

Thank you for this suggestion. Yes, we can’t distinguish in our system between local extinction and emigration. The observed “extinction” of cold-adapted species over 10 years may involve two processes that usually occur in order: first “emigration” and then if can’t emigrate or withstand, “real local dieback”. It should also be included in the legend of Figure 1, as you said. We have modified the legend in Lines 780-781:

“Note that extinction here may include both the emigration of species and then the local extinction of species.”

There is also one part in the Discussion that mentions this on Lines 287-291: “While we cannot truly distinguish in our system between local extinction and emigration, we suspect that given two islands equal except in isolation, and if both lose suitability due to climate change, individuals can easily emigrate from the island nearer to the mainland, while individuals on the more isolated island would be more likely to be trapped in place until the species went locally extinct due to a lack of rescue”.

(7) I also suggest differentiating habitat fragmentation (distances between islands) and habitat amount (area) as explained in Fahrig 2013 (Rethinking patch size and isolation effects: the habitat amount hypothesis) and her latter paper. This will help the reader what lies behind the general trend of fragmentation: fragmentation per se and habitat amount reduction.

Thank you for this suggestion! Habitat fragmentation in this study involves both habitat loss and fragmentation per se. We now give a general definition of habitat fragmentation on Lines 61-63:

“Habitat fragmentation, usually defined as the shifts of continuous habitat into spatially isolated and small patches (Fahrig, 2003), in particular, has been hypothesized to have interactive effects with climate change on community dynamics.”

(8) Line 136: is the "+-" refers to the standard deviation or confidence interval, I suggest being explicit about it once at the start of the results.

Thank you for reminding this. The "+-" refers to the standard deviation (SD). The modified sentence is now on Lines 135-139:

“The number of species detected in surveys on each island across the study period averaged 13.37 ± 6.26 (mean ± SD) species, ranging from 2 to 40 species, with an observed gamma diversity of 60 species. The STI of all 60 birds averaged 19.94 ± 3.58 ℃ (mean ± SD) and ranged from 9.30 ℃ (Cuculus canorus) to 27.20 ℃ (Prinia inornate), with a median of STI is 20.63 ℃ (Appendix 1—figure 2; Appendix 1—figure 3).”

(9) Line 143: please specify the unit of thermophilization.

The unit of thermophilization rate is the change in degree per unit year. Because in all analyses, predictor variables were z-transformed to make their effect comparable. We have added on Line 151:

“When measuring CTI trends for individual islands (expressed as °/ unit year)”

(10) Line 289: check if no word is missing from the sentence.

The sentence is: “In our study, a large proportion (11 out of 15) of warm-adapted species increasing in colonization rate and half (12 out of 23) of cold-adapted species increasing in extinction rate were changing more rapidly on smaller islands.”

Given that we have defined the species that were included in testing the third prediction in both Methods part and Result part: 15 warm-adapted species that increased in colonization rate and 23 cold-adapted species that increased in extinction rate. We now remove this redundant information and rewrote the sentence as below on Lines 300-302:

“In our study, the colonization rate of a large proportion of warm-adapted species (11 out of 15) and the extinction rate of half of old-adapted species (12 out of 23) were increasing more rapidly on smaller islands.”

(11) Line 319: I really miss a concluding statement of your discussion, your results are truly interesting and deserve to be summarized in two or three sentences, and maybe a perspective about how it can inform conservation practices in fragmented settings.

Thank you for this profound suggestion both in Public Review and here. We have added a paragraph to the end of the Discussion, stating how our results can inform conservation, on Lines 339-347:

“Overall, our findings have important implications for conservation practices. Firstly, we confirmed the role of isolation in limiting range shifting. Better connected landscapes should be developed to remove dispersal constraints and facilitate species’ relocation to the best suitable microclimate. Second, small patches can foster the establishment of newly adapted warm-adapted species while large patches can act as refugia for cold-adapted species. Therefore, preserving patches of diverse sizes can act as stepping stones or shelters in a warming climate depending on the thermal affinity of species. These insights are important supplement to the previous emphasis on the role of habitat diversity in fostering (Richard et al., 2021) or reducing (Gaüzère et al., 2017) community-level climate debt.”

(12) Line 335: I suggest " ... the islands has been protected by forbidding logging, ..."

Thanks for this wonderful suggestion. Done. The new sentence is now on Lines 365-366:

“Since lake formation, the islands have been protected by forbidding logging, allowing natural succession pathways to occur.”

(13) Line 345: this speed is unusually high for walking, check the speed.

Sorry for the carelessness, it should be 2.0 km/h. It has been corrected on Lines 375-376:

“In each survey, observers walked along each transect at a constant speed (2.0 km/h) and recorded all the birds seen or heard on the survey islands.”

(14) Line 351: you could add a sentence explaining why that choice of species exclusion was made. Was made from the start of the monitoring program or did you exclude species afterward?

We excluded them afterward. We excluded non-breeding species, nocturnal and crepuscular species, high-flying species passing over the islands (e.g., raptors, swallows) and strongly water-associated birds (e.g., cormorants). These records were recorded during monitoring, including some of them being on the shore of the island or high-flying above the island, and some nocturnal species were just spotted by accident.

We described more details about how to exclude species on Lines 379-387:

“We excluded non-breeding species, nocturnal and crepuscular species, high-flying species passing over the islands (e.g., raptors, swallows) and strongly water-associated birds (e.g., cormorants) from our record. First, our surveys were conducted during the day, so some nocturnal and crepuscular species, such as the owls and nightjars were excluded for inadequate survey design. Second, wagtail, kingfisher, and water birds such as ducks and herons were excluded because we were only interested in forest birds. Third, birds like swallows, and eagles who were usually flying or soaring in the air rather than staying on islands, were also excluded as it was difficult to determine their definite belonging islands. Following these operations, 60 species were finally retained.”

(15) Line 370: I suggest adding the range and median of STI.

Thanks for this good suggestion. The range, mean±SD of STI were already in the Results part, we added the median of STI there as well. The new sentence is now in Results part on Lines 137-139:

“The STI of all 60 birds averaged 19.94 ± 3.58 ℃ (mean ± SD) and ranged from 9.30 ℃ (Cuculus canorus) to 27.20 ℃ (Prinia inornate), with a median of 20.63 ℃ (Appendix 1—figure 2; Appendix 1—figure 3).”

(16) Figure 4.b: Is it possible to be more explicit about what that trend is? the coefficient of the regression Logit(ext/col) ~ year + ...... ?

Thank you for this advice. Your understanding is right: we can interpret it as the coefficient of the ‘year’ effect in the model. More specifically, the ‘year’ effect or temporal trend here is the ‘posterior mean’ of the posterior distribution of ‘year’ in the MSOM (Multi-species Occupancy Model), in the context of the Bayesian framework. We modified this sentence on Lines 811-813:

“ Each point in (b) represents the posterior mean estimate of year in colonization, extinction or occupancy rate for each species.”

(17) Figure 6: is it possible to provide an easily understandable meaning of the prior presented in the Y axis? E.g. "2 corresponds to a 90% probability for a species to go extinct at T+1", if not, please specify that it is the logit of a probability.

Thank you for this question both in Public Review and here. The value on the Y axis indicates the posterior mean of each variable (year, area, isolation and their interaction effects) extracted from the MSOM model, where the logit(extinction rate) or logit(colonization rate) was the response variable. All variables were standardized before analysis to make them comparable. So, positive values indicate positive influence while negative values indicate negative influence. Because the goal of Figure 6 is to display the negative/positive effect, we didn’t back-transform them. Following your advice, we thus modified the caption of Figure 6 (now renumbered as Figure 5, following a comment from Reviewer #3, to move Figure 5 to Figure 4c). The modified title and legends of Figure 5 are on Lines 817-820:

“Figure 5. Posterior estimates of logit-scale parameters related to cold-adapted species’ extinction rates and warm-adapted species’ colonization rates. Points are species-specific posterior means on the logit-scale, where parameters >0 indicate positive effects (on extinction [a] or colonization [b]) and parameters <0 indicate negative effects.”

(18) Line 773: points in blue only are significant? I suggest "points in color".

Thank you for your reminder. Points in blue and orange are all significant. We have revised the sentence on Line 823:

“Points in blue/orange indicate significant effects.”

These are all small suggestions that may help you improve the readability of the final manuscript. I warmly thank you for the opportunity to review this impressive study.

We appreciate your careful review and profound suggestions. We believe these modifications will improve the final manuscript.

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations For The Authors):

I have a few minor suggestions for paper revision for your otherwise excellent manuscript. I wish to emphasize that it was a pleasure to read the manuscript and that I especially enjoyed a very nice flow throughout the ms from a nicely rounded introduction that led well into the research questions and hypotheses all the way to a good and solid discussion.

Thank you very much for your review and recognition. We have carefully checked all recommendations and addressed them in the manuscript.

(1) L 63: space before the bracket missing and I suggest moving the reference to the end of the sentence (directly after habitat fragmentation does not seem to make sense).

Thank you very much for this suggestion. The missed space was added, and the reference has been moved to the end of the sentence. We also add a general definition of habitat fragmentation. The new sentence is on Lines 61-64:

“Habitat fragmentation, usually defined as the shifts of continuous habitat into spatially isolated and small patches (Fahrig, 2003), in particular, has been hypothesized to have interactive effects with climate change on community dynamics.”

(2) L 102: I suggest to write "benefitting ..." instead.

Done.

(3) L 103: higher extinction rates (add "s").

Done.

(4) L 104: this should probably say "emigrate" and "climate warming".

Done.

(5) L 130-133: this is true for emigration (more isolated islands show slower emigration). But what about increased local extinction, especially for small and isolated islands? Especially since you mentioned later in the manuscript that often emigration and extinction are difficult to identify or differentiate. Might be worth a thought here or somewhere in the discussion?

Thank you for this good question. I would like to answer it in two aspects:

Yes, we can’t distinguish between true local extinction and emigration. The observed local “extinction” of cold-adapted species over 10 years may involve two processes that usually occur in order: first “emigration” and then, if can’t emigrate or withstand, “real local dieback”. Over 10 years, the cold-adapted species would have to tolerate before real extinction on remote islands because of disperse limitation, while on less isolated islands it would be easy to emigrate and find a more suitable habitat for the same species. Consequently, it’s harder for us to observe “extinction” of species on more isolated islands, while it’s easier to observe “fake extinct” of species on less isolated islands due to emigration. As a result, the observed extinction rate is expected to increase more sharply for species on less remote islands, while the observed extinction rate is expected to increase relatively moderately for the same species on remote islands.

We have modified the legend of Figure 1 on Lines 780-781:

“Note that extinction here may include both the emigration of species and then the local extinction of species.”

There is also one part in the Discussion that mentions this on Lines 287-291: “While we cannot truly distinguish in our system between local extinction and emigration, we suspect that given two islands equal except in isolation, if both lose suitability due to climate change, individuals can easily emigrate from the island nearer to the mainland, while individuals on the more isolated island would be more likely to be trapped in place until the species went locally extinct due to a lack of rescue”.

Besides, you said “But what about increased local extinction, especially for small and isolated islands?”, I think you are mentioning the “high extinction rate per se on remote islands”. We want to test the “trend” of extinction rate on a temporal scale, rather than the extinction rate per se on a spatial scale. Even though species have a high extinction rate on remote islands, it can also show a slower changing rate in time.

I hope these answers solve the problem.

(6) L 245: I think this is the first time the acronym appears in the ms (as the methods come after the discussion), so please write the full name here too.

Thank you for pointing out this. I realized “Thousand Island Lake” appears for the first time in the last paragraph of the Introduction part. So we add “TIL” there on Lines 108-109:

“Here, we use 10 years of bird community data in a subtropical land-bridge island system (Thousand Island Lake, TIL, China, Figure 2) during a period of consistent climatic warming.”

(7) L 319: this section could end with a summary statement on idiosyncratic responses (i.e. some variation in the responses you found among the species) and the potential reasons for this, such as e.g. the role of other species traits or interactions, as well as other ways to measure habitat fragmentation (see main comments in public review).

Thank you for this suggestion both in Public Review and here. We added a summary statement about the reasons for idiosyncratic responses on Lines 334-338:

“Overall, these idiosyncratic responses reveal several possible mechanisms in regulating species' climate responses, including resource demands and biological interactions like competition and predation. Future studies are needed to take these factors into account to understand the complex mechanisms by which habitat loss meditates species range shifts.”