Revealing a hidden conducting state by manipulating the intracellular domains in KV10.1 exposes the coupling between two gating mechanisms

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

eLife assessment

This valuable study examines the role of the interaction between cytoplasmic N- and C-terminal domains in voltage-dependent gating of Kv10.1 channels. The authors suggest that they have identified a hidden open state in Kv10.1 mutant channels, thus providing a window for observing early conformational transitions associated with channel gating. The evidence supporting the major conclusions is solid, but additional work is required to determine the molecular mechanism underlying the observations in this study. Learning the molecular mechanisms could be significant in understanding the gating mechanisms of the KCNH family and will appeal to biophysicists interested in ion channels and physiologists interested in cancer biology.

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

- Reading List (BiophysicsColab)

Abstract

The KCNH family of potassium channels serves relevant physiological functions in both excitable and non-excitable cells, reflected in the massive consequences of mutations or pharmacological manipulation of their function. This group of channels shares structural homology with other voltage-gated K + channels, but the mechanisms of gating in this family show significant differences with respect to the canonical electromechanical coupling in these molecules. In particular, the large intracellular domains of KCNH channels play a crucial role in gating that is still only partly understood. Using KCNH1 (K V 10.1) as a model, we have characterized the behavior of a series of modified channels that could not be explained by the current models. With electrophysiological and biochemical methods combined with mathematical modeling, we show that the uncovering of an open state can explain the behavior of the mutants. This open state, which is not detectable in wild-type channels, appears to lack the rapid flicker block of the conventional open state. Because it is accessed from deep closed states, it elucidates intermediate gating events well ahead of channel opening in the wild type. This allowed us to study gating steps prior to opening, which, for example, explain the mechanism of gating inhibition by Ca 2+ -Calmodulin and generate a model that describes the characteristic features of KCNH channels gating.

Article activity feed

-

-

-

-

eLife assessment

This valuable study examines the role of the interaction between cytoplasmic N- and C-terminal domains in voltage-dependent gating of Kv10.1 channels. The authors suggest that they have identified a hidden open state in Kv10.1 mutant channels, thus providing a window for observing early conformational transitions associated with channel gating. The evidence supporting the major conclusions is solid, but additional work is required to determine the molecular mechanism underlying the observations in this study. Learning the molecular mechanisms could be significant in understanding the gating mechanisms of the KCNH family and will appeal to biophysicists interested in ion channels and physiologists interested in cancer biology.

-

Gating of Kv10 channels is unique because it involves coupling between non-domain swapped voltage sensing domains, a domain-swapped cytoplasmic ring assembly formed by the N- and C-termini, and the pore domain. Recent structural data suggests that activation of the voltage sensing domain relieves a steric hindrance to pore opening, but the contribution of the cytoplasmic domain to gating is still not well understood. This aspect is of particular importance because proteins like calmodulin interact with the cytoplasmic domain to regulate channel activity. The effects of calmodulin (CaM) in WT and mutant channels with disrupted cytoplasmic gating ring assemblies are contradictory, resulting in inhibition or activation, respectively. The underlying mechanism for these discrepancies is not understood. In the present manuscript, Reham …

Gating of Kv10 channels is unique because it involves coupling between non-domain swapped voltage sensing domains, a domain-swapped cytoplasmic ring assembly formed by the N- and C-termini, and the pore domain. Recent structural data suggests that activation of the voltage sensing domain relieves a steric hindrance to pore opening, but the contribution of the cytoplasmic domain to gating is still not well understood. This aspect is of particular importance because proteins like calmodulin interact with the cytoplasmic domain to regulate channel activity. The effects of calmodulin (CaM) in WT and mutant channels with disrupted cytoplasmic gating ring assemblies are contradictory, resulting in inhibition or activation, respectively. The underlying mechanism for these discrepancies is not understood. In the present manuscript, Reham Abdelaziz and collaborators use electrophysiology, biochemistry and mathematical modeling to describe how mutations and deletions that disrupt inter-subunit interactions at the cytoplasmic gating ring assembly affect Kv10.1 channel gating and modulation by CaM. In the revised manuscript, additional information is provided to allow readers to identify within the Kv10.1 channel structure the location of E600R, one of the key channel mutants analyzed in this study. However, the mechanistic role of the cytoplasmic domains that this study focuses on, as well as the location of the ΔPASCap deletion and other perturbations investigated in the study remain difficult to visualize without additional graphical information.

The authors focused mainly on two structural perturbations that disrupt interactions within the cytoplasmic domain, the E600R mutant and the ΔPASCap deletion. By expressing mutants in oocytes and recording currents using Two Electrode Voltage-Clamp (TEV), it is found that both ΔPASCap and E600R mutants have biphasic conductance-voltage (G-V) relations and exhibit activation and deactivation kinetics with multiple voltage-dependent components. Importantly, the mutant-specific component in the G-V relations is observed at negative voltages where WT channels remain closed. The authors argue that the biphasic behavior in the G-V relations is unlikely to result from two different populations of channels in the oocytes, because they found that the relative amplitude between the two components in the G-V relations was highly reproducible across individual oocytes that otherwise tend to show high variability in expression levels. Instead, the G-V relations for all mutant channels could be well described by an equation that considers two open states O1 and O2, and a transition between them; O1 appeared to be unaffected by any of the structural manipulations tested (i.e. E600R, ΔPASCap, and other deletions) whereas the parameters for O2 and the transition between the two open states were different between constructs. The O1 state is not observed in WT channels and is hypothesized to be associated with voltage sensor activation. O2 represents the open state that is normally observed in WT channels and is speculated to be associated with conformational changes within the cytoplasmic gating ring that follow voltage sensor activation, which could explain why the mutations and deletions disrupting cytoplasmic interactions affect primarily O2.

Severing the covalent link between the voltage sensor and pore reduced O1 occupancy in one of the deletion constructs. Although this observation is consistent with the hypothesis that voltage-sensor activation drives entry into O1, this result is not conclusive. Structural as well as functional data has established that the coupling of the voltage sensor and pore does not entirely rely on the S4-S5 covalent linker between the sensor and the pore, and thus the severed construct could still retain coupling through other mechanisms, which is consistent with the prominent voltage dependence that is observed. If both states O1 and O2 require voltage sensor activation, it is unclear why the severed construct would affect state O1 primarily, as suggested in the manuscript, as opposed to decreasing occupancy of both open states. In line with this argument, the presence of Mg2+ in the extracellular solution affected both O1 and O2. This finding suggests that entry into both O1 and O2 requires voltage-sensor activation because Mg2+ ions are known to stabilize the voltage sensor in its most deactivated conformations.

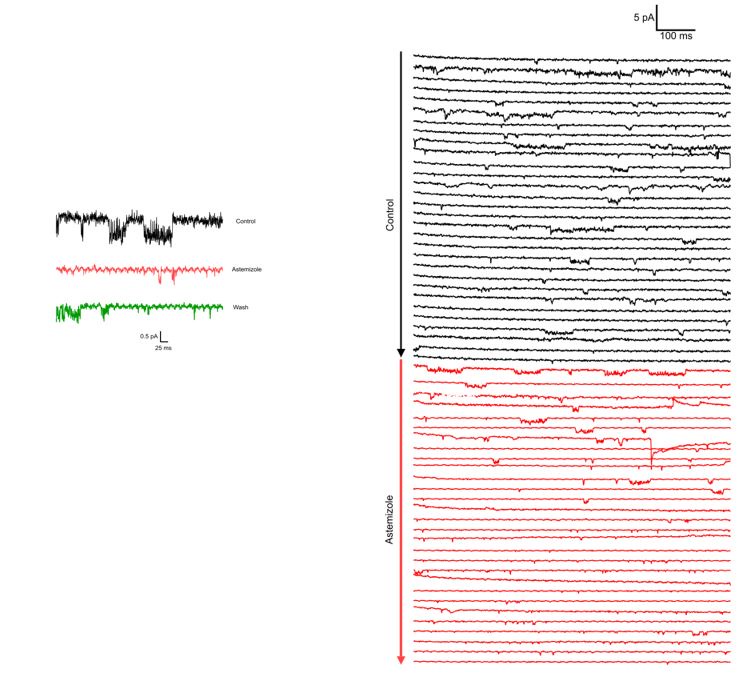

Activation towards and closure from O1 is slow, whereas channels close rapidly from O2. A rapid alternating pulse protocol was used to take advantage of the difference in activation and deactivation kinetics between the two open components in the mutants and thus drive an increasing number of channels towards state O1. Currents activated by the alternating protocol reached larger amplitudes than those elicited by a long depolarization to the same voltage. This finding is interpreted as an indication that O1 has a larger macroscopic conductance than O2. In the revised manuscript, the authors performed single-channel recordings to determine why O1 and O2 have different macroscopic conductance. The results show that at voltages where the state O1 predominates, channels exhibited longer open times and overall higher open probability, whereas at more depolarized voltages where occupancy of O2 increases, channels exhibited more flickery gating behavior and decreased open probability. These results are informative but not conclusive since single-channel amplitudes could not be resolved at strong depolarizations, limiting the extent to which the data could be analyzed. In the last revision, the authors have included one representative example showing inhibition of single channel activity by the Kv10-specific inhibitor astemizole. Group data analysis would be needed to conclusively establish that the currents that were recorded indeed correspond to Kv10 channels.

It is shown that conditioning pulses to very negative voltages result in mutant channel currents that are larger and activate more slowly than those elicited at the same voltage but starting from less negative conditioning pulses. In voltage-activated curves, O1 occupancy is shown to be favored by increasingly negative conditioning voltages. This is interpreted as indicating that O1 is primarily accessed from deeply closed states in which voltage sensors are in their most deactivated position. Consistently, a mutation that destabilizes these deactivated states is shown to largely suppress the first component in voltage-activation curves for both ΔPASCap and E600R channels.

The authors then address the role of the hidden O1 state in channel regulation by calcium-calmodulin (CaM). Stimulating calcium entry into oocytes with ionomycin and thapsigargin, assumed to enhance CaM-dependent modulation, resulted in preferential potentiation of the first component in ΔPASCap and E600R channels. This potentiation was attenuated by including an additional mutation that disfavors deeply closed states. Together, these results are interpreted as an indication that calcium-CaM preferentially stabilizes deeply closed states from which O1 can be readily accessed in mutant channels, thus favoring current activation. In WT channels lacking a conducting O1 state, CaM stabilizes deeply closed states and is therefore inhibitory. It is found that the potentiation of ΔPASCap and E600R by CaM is more strongly attenuated by mutations in the channel that are assumed to disrupt interaction with the C-terminal lobe of CaM than mutations assumed to affect interaction with the N-terminal lobe. These results are intriguing but difficult to interpret in mechanistic terms. The strong effect that calcium-CaM had on the occupancy of the O1 state in the mutants raises the possibility that O1 can be only observed in channels that are constitutively associated with CaM. To address this, a biochemical pull-down assay was carried out to establish that only a small fraction of channels are associated with CaM under baseline conditions. These CaM experiments are potentially very interesting and could have wide physiological relevance. However, the approach utilized to activate CaM is indirect and could result in additional non-specific effects on the oocytes that could affect the results.

Finally, a mathematical model is proposed consisting of two layers involving two activation steps for the voltage sensor, and one conformational change in the cytoplasmic gating ring - completion of both sets of conformational changes is required to access state O2, but accessing state O1 only requires completion of the first voltage-sensor activation step in the four subunits. The model qualitatively reproduces most major findings on the mutants. Although the model used is highly symmetric and appears simple, the mathematical form used for the rate constants in the model adds a layer of complexity to the model that makes mechanistic interpretations difficult. In addition, many transitions that from a mechanistic standpoint should not depend on voltage were assigned a voltage dependence in the model. These limitations diminish the mechanistic insight that can be reliably extracted from the model.

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

We appreciate the feedback provided and refer to our previous response for detailed explanations regarding our decisions on some of the recommendations made by the referees and editors. We have introduced changes as follows:

• We added a supplementary Figure to Figure 5 to show inhibition by Astemizole at the single channel level.

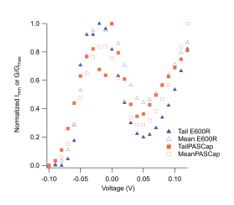

• We have corrected Figure 7A, where the normalized current did not reach 1 as a maximum. We had overlooked that this is expected when the prepulse was -160 mV, and the IV is strongly biphasic, but not when coming from -100 mV. We are thankful for this observation, which served to identify that the values for one of the cells were inverted with respect to the others (the sequence of stimuli was different during recording, and this …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

We appreciate the feedback provided and refer to our previous response for detailed explanations regarding our decisions on some of the recommendations made by the referees and editors. We have introduced changes as follows:

• We added a supplementary Figure to Figure 5 to show inhibition by Astemizole at the single channel level.

• We have corrected Figure 7A, where the normalized current did not reach 1 as a maximum. We had overlooked that this is expected when the prepulse was -160 mV, and the IV is strongly biphasic, but not when coming from -100 mV. We are thankful for this observation, which served to identify that the values for one of the cells were inverted with respect to the others (the sequence of stimuli was different during recording, and this information got lost in the analysis procedure). We have corrected this and made sure that such a mistake had not happened anywhere else.

• Finally, we have corrected a typo in the discussion, as indicated in the review.

We include a version with changes marked and a clean version of the manuscript.

-

-

eLife assessment

This valuable study examines the role of the interaction between cytoplasmic N- and C-terminal domains in voltage-dependent gating of Kv10.1 channels. The authors claim to have identified a hidden open state in Kv10.1 mutant channels, thus providing a window for observing early conformational transitions associated with channel gating. The evidence supporting the major conclusions is incomplete, however, and additional work is required to determine the molecular mechanism underlying the observations in this study. With the experimental conditions clarified and the mechanistic interpretations addressed, this work could be significant in understanding the gating mechanisms of the KCNH family and will appeal to biophysicists interested in ion channels and physiologists interested in cancer biology.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Gating of Kv10 channels is unique because it involves coupling between non-domain swapped voltage sensing domains, a domain-swapped cytoplasmic ring assembly formed by the N- and C-termini, and the pore domain. Recent structural data suggests that activation of the voltage sensing domain relieves a steric hindrance to pore opening, but the contribution of the cytoplasmic domain to gating is still not well understood. This aspect is of particular importance because proteins like calmodulin interact with the cytoplasmic domain to regulate channel activity. The effects of calmodulin (CaM) in WT and mutant channels with disrupted cytoplasmic gating ring assemblies are contradictory, resulting in inhibition or activation, respectively. The underlying mechanism for these discrepancies is not understood. In the …

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Gating of Kv10 channels is unique because it involves coupling between non-domain swapped voltage sensing domains, a domain-swapped cytoplasmic ring assembly formed by the N- and C-termini, and the pore domain. Recent structural data suggests that activation of the voltage sensing domain relieves a steric hindrance to pore opening, but the contribution of the cytoplasmic domain to gating is still not well understood. This aspect is of particular importance because proteins like calmodulin interact with the cytoplasmic domain to regulate channel activity. The effects of calmodulin (CaM) in WT and mutant channels with disrupted cytoplasmic gating ring assemblies are contradictory, resulting in inhibition or activation, respectively. The underlying mechanism for these discrepancies is not understood. In the present manuscript, Reham Abdelaziz and collaborators use electrophysiology, biochemistry and mathematical modeling to describe how mutations and deletions that disrupt inter-subunit interactions at the cytoplasmic gating ring assembly affect Kv10.1 channel gating and modulation by CaM. In the revised manuscript, additional information is provided to allow readers to identify within the Kv10.1 channel structure the location of E600R, one of the key channel mutants analyzed in this study. However, the mechanistic role of the cytoplasmic domains that this study focuses on, as well as the location of the ΔPASCap deletion and other perturbations investigated in the study remain difficult to visualize without additional graphical information. This can make it challenging for readers to connect the findings presented in the study with a structural mechanism of channel function.

The authors focused mainly on two structural perturbations that disrupt interactions within the cytoplasmic domain, the E600R mutant and the ΔPASCap deletion. By expressing mutants in oocytes and recording currents using Two Electrode Voltage-Clamp (TEV), it is found that both ΔPASCap and E600R mutants have biphasic conductance-voltage (G-V) relations and exhibit activation and deactivation kinetics with multiple voltage-dependent components. Importantly, the mutant-specific component in the G-V relations is observed at negative voltages where WT channels remain closed. The authors argue that the biphasic behavior in the G-V relations is unlikely to result from two different populations of channels in the oocytes, because they found that the relative amplitude between the two components in the G-V relations was highly reproducible across individual oocytes that otherwise tend to show high variability in expression levels. Instead, the G-V relations for all mutant channels could be well described by an equation that considers two open states O1 and O2, and a transition between them; O1 appeared to be unaffected by any of the structural manipulations tested (i.e. E600R, ΔPASCap, and other deletions) whereas the parameters for O2 and the transition between the two open states were different between constructs. The O1 state is not observed in WT channels and is hypothesized to be associated with voltage sensor activation. O2 represents the open state that is normally observed in WT channels and is speculated to be associated with conformational changes within the cytoplasmic gating ring that follow voltage sensor activation, which could explain why the mutations and deletions disrupting cytoplasmic interactions affect primarily O2.

Severing the covalent link between the voltage sensor and pore reduced O1 occupancy in one of the deletion constructs. Although this observation is consistent with the hypothesis that voltage-sensor activation drives entry into O1, this result is not conclusive. Structural as well as functional data has established that the coupling of the voltage sensor and pore does not entirely rely on the S4-S5 covalent linker between the sensor and the pore, and thus the severed construct could still retain coupling through other mechanisms, which is consistent with the prominent voltage dependence that is observed. If both states O1 and O2 require voltage sensor activation, it is unclear why the severed construct would affect state O1 primarily, as suggested in the manuscript, as opposed to decreasing occupancy of both open states. In line with this argument, the presence of Mg2+ in the extracellular solution affected both O1 and O2. This finding suggests that entry into both O1 and O2 requires voltage-sensor activation because Mg2+ ions are known to stabilize the voltage sensor in its most deactivated conformations.

Activation towards and closure from O1 is slow, whereas channels close rapidly from O2. A rapid alternating pulse protocol was used to take advantage of the difference in activation and deactivation kinetics between the two open components in the mutants and thus drive an increasing number of channels towards state O1. Currents activated by the alternating protocol reached larger amplitudes than those elicited by a long depolarization to the same voltage. This finding is interpreted as an indication that O1 has a larger macroscopic conductance than O2. In the revised manuscript, the authors performed single-channel recordings to determine why O1 and O2 have different macroscopic conductance. The results show that at voltages where the state O1 predominates, channels exhibited longer open times and overall higher open probability, whereas at more depolarized voltages where occupancy of O2 increases, channels exhibited more flickery gating behavior and decreased open probability. These results are informative but not conclusive because additional details about how experiments were conducted, and group data analysis are missing. Importantly, results showing inhibition of single ΔPASCap channels by a Kv10-specific inhibitor are mentioned but not shown or quantitated - these data are essential to establish that the new O1 conductance indeed represents Kv10 channel activity.

It is shown that conditioning pulses to very negative voltages result in mutant channel currents that are larger and activate more slowly than those elicited at the same voltage but starting from less negative conditioning pulses. In voltage-activated curves, O1 occupancy is shown to be favored by increasingly negative conditioning voltages. This is interpreted as indicating that O1 is primarily accessed from deeply closed states in which voltage sensors are in their most deactivated position. Consistently, a mutation that destabilizes these deactivated states is shown to largely suppress the first component in voltage-activation curves for both ΔPASCap and E600R channels.

The authors then address the role of the hidden O1 state in channel regulation by calmodulation. Stimulating calcium entry into oocytes with ionomycin and thapsigarging, assumed to enhance CaM-dependent modulation, resulted in preferential potentiation of the first component in ΔPASCap and E600R channels. This potentiation was attenuated by including an additional mutation that disfavors deeply closed states. Together, these results are interpreted as an indication that calcium-CaM preferentially stabilizes deeply closed states from which O1 can be readily accessed in mutant channels, thus favoring current activation. In WT channels lacking a conducting O1 state, CaM stabilizes deeply closed states and is therefore inhibitory. It is found that the potentiation of ΔPASCap and E600R by CaM is more strongly attenuated by mutations in the channel that are assumed to disrupt interaction with the C-terminal lobe of CaM than mutations assumed to affect interaction with the N-terminal lobe. These results are intriguing but difficult to interpret in mechanistic terms. The strong effect that calcium-CaM had on the occupancy of the O1 state in the mutants raises the possibility that O1 can be only observed in channels that are constitutively associated with CaM. To address this, a biochemical pull-down assay was carried out to establish that only a small fraction of channels are associated with CaM under baseline conditions. These CaM experiments are potentially very interesting and could have wide physiological relevance. However, the approach utilized to activate CaM is indirect and could result in additional non-specific effects on the oocytes that could affect the results.

Finally, a mathematical model is proposed consisting of two layers involving two activation steps for the voltage sensor, and one conformational change in the cytoplasmic gating ring - completion of both sets of conformational changes is required to access state O2, but accessing state O1 only requires completion of the first voltage-sensor activation step in the four subunits. The model qualitatively reproduces most major findings on the mutants. Although the model used is highly symmetric and appears simple, the mathematical form used for the rate constants in the model adds a layer of complexity to the model that makes mechanistic interpretations difficult. In addition, many transitions that from a mechanistic standpoint should not depend on voltage were assigned a voltage dependence in the model. These limitations diminish the overall usefulness of the model which is prominently presented in the manuscript. The most important mechanistic assumptions in the model are not addressed experimentally, such as the proposition that entry into O1 depends on the opening of the transmembrane pore gate, whereas entry into O2 involves gating ring transitions - it is unclear why O2 would require further gating ring transitions to conduct ions given that the gating ring can already support permeation by O1 without any additional conformational changes.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In the present manuscript, Abdelaziz and colleagues interrogate the gating mechanisms of Kv10.1, an important voltage-gated K+ channel in cell cycle and cancer physiology. At the molecular level, Kv10.1 is regulated by voltage and Ca-CaM. Structures solved using Cryo-EM for Kv10.1 as well as other members of the KCNH family (Kv11 and Kv12) show channels that do not contain a structured S4-S5 linker imposing therefore a non-domain swapped architecture in the transmembrane region. However, the cytoplasmatic N- and C- terminal domains interact in a domain swapped manner forming a gating ring. The N-terminal domain (PAS domain) of one subunit is located close to the intracellular side of the voltage sensor domain and interacts with the C-terminal domain (CNBHD domain) of the neighbor subunit. Mutations in the …

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In the present manuscript, Abdelaziz and colleagues interrogate the gating mechanisms of Kv10.1, an important voltage-gated K+ channel in cell cycle and cancer physiology. At the molecular level, Kv10.1 is regulated by voltage and Ca-CaM. Structures solved using Cryo-EM for Kv10.1 as well as other members of the KCNH family (Kv11 and Kv12) show channels that do not contain a structured S4-S5 linker imposing therefore a non-domain swapped architecture in the transmembrane region. However, the cytoplasmatic N- and C- terminal domains interact in a domain swapped manner forming a gating ring. The N-terminal domain (PAS domain) of one subunit is located close to the intracellular side of the voltage sensor domain and interacts with the C-terminal domain (CNBHD domain) of the neighbor subunit. Mutations in the intracellular domains has a profound effect in the channel gating. The complex network of interactions between the voltage-sensor and the intracellular domains makes the PAS domain a particularly interesting domain of the channel to study as responsible for the coupling between the voltage sensor domains and the intracellular gating ring.

The coupling between the voltage-sensor domain and the gating ring is not fully understood and the authors aim to shed light into the details of this mechanism. In order to do that, they use well established techniques such as site-directed mutagenesis, electrophysiology, biochemistry and mathematical modeling. In the present work, the authors propose a two open state model that arises from functional experiments after introducing a deletion on the PAS domain (ΔPAS Cap) or a point mutation (E600R) in the CNBHD domain. The authors measure a bi-phasic G-V curve with these mutations and assign each phase as two different open states, one of them not visible on the WT and only unveiled after introducing the mutations. The hypothesis proposed by the authors could change the current paradigm in the current understanding for Kv10.1 and it is quite extraordinary; therefore, it requires extraordinary evidence to support it.

STRENGTHS: The authors use adequate techniques such as electrophysiology and site-directed mutagenesis to address the gating changes introduced by the molecular manipulations. They also use appropriate mathematical modeling to build a Markov model and identify the mechanism behind the gating changes.

WEAKNESSES: The results presented by the authors do not fully support their conclusions since they could have alternative explanations. The authors base their primary hypothesis on the bi-phasic behavior of a calculated G-V curve that do not match the tail behavior, the experimental conditions used in the present manuscript introduce uncertainties, weakening their conclusions and complicating the interpretation of the results. Therefore, their experimental conditions need to be revisited

I have some concerns related to the following points:

(1) Biphasic gating behavior

The authors use the TEVC technique in oocytes extracted surgically from Xenopus Leavis frogs. The method is well established and is adequate to address ion channel behavior. The experiments are performed in chloride-based solutions which present a handicap when measuring outward rectifying currents at very depolarizing potentials due to the presence of calcium activated chloride channel expressed endogenously in the oocytes; these channels will open and rectify chloride intracellularly adding to the outward rectifying traces during the test pulse.

The authors calculate their G-V curves from the test pulse steady-state current instead of using the tail currents. The conductance measurements are normally taken from the 'tail current' because tails are measured at a fix voltage hence maintaining the driving force constant. Calculating the conductance from the traces should not be a problem, however, in the present manuscript, the traces and the tail currents do not agree. The tail traces shown in Fig1E do not show an increasing current amplitude in the voltage range from +50mV to +120mV, they seem to have reached a 'saturation state', suggesting that the traces from the test pulse contain an inward chloride current contamination. In addition, this second component identified by the authors as a second open state appears after +50mV and seems to never saturate. The normalization to the maximum current level during the test pulse, exaggerates this second component on the calculated G-V curve. It's worth noticing that the ΔPASCap mutant experiments on Fig 5 in Mes based solutions do not show that second component on the G-V.Because these results are the foundation for their two open state hypotheses, I will strongly suggest the authors to repeat all their Chloride-based experiments in Mes-based solutions to eliminate the undesired chloride contribution to the mutants current and clarify the contribution of the mutations to the Kv10.1 gating.

(2) Two step gating mechanism.

The authors interpret the results obtained with the ΔPASCap and the E600R as two step gating mechanisms containing two open states (O1 and O2) and assign them to the voltage sensor movement and gating ring rotation respectively. It is not clear, however how the authors assign the two open states.

The results show how the first component is conserved amongst mutations; however, the second one is not. The authors attribute the second component, hence the second open state to the movement of the gating ring. This scenario seems unlikely since there is a clear voltage-dependence of the second component that will suggest an implication of a voltage-sensing current.The split channel experiment is interesting but needs more explanation. I assume the authors expressed the 2 parts of the split channel (1-341 and 342-end), however Tomczak et al showed in 2017 how the split presents a constitutively activated function with inward currents that are not visible here, this point needs clarification.

Moreover, the authors assume that the mutations introduced uncover a new open state, however the traces presented for the mutations suggest that other explanations are possible. Other gating mechanisms like inactivation from the closed state, can be introduced by the mutations. The traces presented for ΔPASCap but specially E600R present clear 'hooked tails', a direct indicator of a populations of inactive channels during the test pulse that recover from inactivation upon repolarization (Tristani-Firouzi M, Sanguinetti MC. J Physiol. 1998). The results presented by the authors can be alternatively explained with a change in the equilibrium between the close to inactivated/recovery from inactivation to the open state. Finally, the authors state that they do not detect "cumulative inactivation after repeated depolarization" but that is considering inactivation only from the open state and ignoring the possibility of the existence of close state inactivation or, that like in hERG, that the channel inactivates faster that what it activates (Smith PL, Yellen G. J Gen Physiol. 2002).

(3) Single channel conductance.

The single channels experiments are a great way to assess the different conductance of single channel openings, unfortunately the authors cannot measure accurately different conductances for the two proposed open states. The Markov Model built by the authors, disagrees with their interpretation of the experimental results assigning the exact same conductance to the two modeled open states. To interpret the mutant data, it is needed to add data with the WT for comparison and in presence of specific blockers. -

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the current reviews.

Gating of Kv10 channels is unique because it involves coupling between non-domain swapped voltage sensing domains, a domain-swapped cytoplasmic ring assembly formed by the N- and C-termini, and the pore domain. Recent structural data suggests that activation of the voltage sensing domain relieves a steric hindrance to pore opening, but the contribution of the cytoplasmic domain to gating is still not well understood. This aspect is of particular importance because proteins like calmodulin interact with the cytoplasmic domain to regulate channel activity. The effects of calmodulin (CaM) in WT and mutant channels with disrupted cytoplasmic gating ring assemblies are contradictory, resulting in inhibition or activation, respectively. The underlying mechanism …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the current reviews.

Gating of Kv10 channels is unique because it involves coupling between non-domain swapped voltage sensing domains, a domain-swapped cytoplasmic ring assembly formed by the N- and C-termini, and the pore domain. Recent structural data suggests that activation of the voltage sensing domain relieves a steric hindrance to pore opening, but the contribution of the cytoplasmic domain to gating is still not well understood. This aspect is of particular importance because proteins like calmodulin interact with the cytoplasmic domain to regulate channel activity. The effects of calmodulin (CaM) in WT and mutant channels with disrupted cytoplasmic gating ring assemblies are contradictory, resulting in inhibition or activation, respectively. The underlying mechanism for these discrepancies is not understood. In the present manuscript, Reham Abdelaziz and collaborators use electrophysiology, biochemistry and mathematical modeling to describe how mutations and deletions that disrupt inter-subunit interactions at the cytoplasmic gating ring assembly affect Kv10.1 channel gating and modulation by CaM. In the revised manuscript, additional information is provided to allow readers to identify within the Kv10.1 channel structure the location of E600R, one of the key channel mutants analyzed in this study. However, the mechanistic role of the cytoplasmic domains that this study focuses on, as well as the location of the ΔPASCap deletion and other perturbations investigated in the study remain difficult to visualize without additional graphical information. This can make it challenging for readers to connect the findings presented in the study with a structural mechanism of channel function.

The authors focused mainly on two structural perturbations that disrupt interactions within the cytoplasmic domain, the E600R mutant and the ΔPASCap deletion. By expressing mutants in oocytes and recording currents using Two Electrode Voltage-Clamp (TEV), it is found that both ΔPASCap and E600R mutants have biphasic conductance-voltage (G-V) relations and exhibit activation and deactivation kinetics with multiple voltage-dependent components. Importantly, the mutant-specific component in the G-V relations is observed at negative voltages where WT channels remain closed. The authors argue that the biphasic behavior in the G-V relations is unlikely to result from two different populations of channels in the oocytes, because they found that the relative amplitude between the two components in the G-V relations was highly reproducible across individual oocytes that otherwise tend to show high variability in expression levels. Instead, the G-V relations for all mutant channels could be well described by an equation that considers two open states O1 and O2, and a transition between them; O1 appeared to be unaffected by any of the structural manipulations tested (i.e. E600R, ΔPASCap, and other deletions) whereas the parameters for O2 and the transition between the two open states were different between constructs. The O1 state is not observed in WT channels and is hypothesized to be associated with voltage sensor activation. O2 represents the open state that is normally observed in WT channels and is speculated to be associated with conformational changes within the cytoplasmic gating ring that follow voltage sensor activation, which could explain why the mutations and deletions disrupting cytoplasmic interactions affect primarily O2.

Severing the covalent link between the voltage sensor and pore reduced O1 occupancy in one of the deletion constructs. Although this observation is consistent with the hypothesis that voltage-sensor activation drives entry into O1, this result is not conclusive. Structural as well as functional data has established that the coupling of the voltage sensor and pore does not entirely rely on the S4-S5 covalent linker between the sensor and the pore, and thus the severed construct could still retain coupling through other mechanisms, which is consistent with the prominent voltage dependence that is observed. If both states O1 and O2 require voltage sensor activation, it is unclear why the severed construct would affect state O1 primarily, as suggested in the manuscript, as opposed to decreasing occupancy of both open states. In line with this argument, the presence of Mg2+ in the extracellular solution affected both O1 and O2. This finding suggests that entry into both O1 and O2 requires voltage-sensor activation because Mg2+ ions are known to stabilize the voltage sensor in its most deactivated conformations.

We agree with the reviewer that access to both states requires a conformational change in the voltage sensor. This was stated in our revised article: “In contrast, to enter O2, all subunits must complete both voltage sensor transitions and the collective gating ring transition.” We interpret the two gating steps as sequential; the effective rotation of the intracellular ring would happen only once the sensor is in its fully activated position.

We also agree that the S4-S5 segment cannot be the only interaction mechanism, as we demonstrated in our earlier work (Lörinczi et al., 2015; Tomczak et al., 2017).

Activation towards and closure from O1 is slow, whereas channels close rapidly from O2. A rapid alternating pulse protocol was used to take advantage of the difference in activation and deactivation kinetics between the two open components in the mutants and thus drive an increasing number of channels towards state O1. Currents activated by the alternating protocol reached larger amplitudes than those elicited by a long depolarization to the same voltage. This finding is interpreted as an indication that O1 has a larger macroscopic conductance than O2. In the revised manuscript, the authors performed single-channel recordings to determine why O1 and O2 have different macroscopic conductance. The results show that at voltages where the state O1 predominates, channels exhibited longer open times and overall higher open probability, whereas at more depolarized voltages where occupancy of O2 increases, channels exhibited more flickery gating behavior and decreased open probability. These results are informative but not conclusive because additional details about how experiments were conducted, and group data analysis are missing. Importantly, results showing inhibition of single ΔPASCap channels by a Kv10-specific inhibitor are mentioned but not shown or quantitated - these data are essential to establish that the new O1 conductance indeed represents Kv10 channel activity.

We observed the activity of a channel compatible with Kv10.1 ΔPAS-Cap (long openings at low-moderate potentials, very short flickery activity at strong depolarizations) in 12 patches from oocytes obtained from different frog operations over a period of two and a half months once the experimental conditions could be established. As stated in the text, we did not proceed to generate amplitude histograms because we could not resolve clear single-channel events at strong depolarizations. Astemizole abolished the activity and (remarkably) strongly reduced the noise in traces at strong depolarizations, which we interpret as partially caused by flicker openings.

Author response image 1.

We include two example recordings of Astemizole application (100µM) on two different patches. Both recordings are performed at -60 mV (to decrease the likelihood that the channel visits O2) with 100 mM internal and 60 mM external K+. In both cases, the traces in Astemizole are presented in red.

It is shown that conditioning pulses to very negative voltages result in mutant channel currents that are larger and activate more slowly than those elicited at the same voltage but starting from less negative conditioning pulses. In voltage-activated curves, O1 occupancy is shown to be favored by increasingly negative conditioning voltages. This is interpreted as indicating that O1 is primarily accessed from deeply closed states in which voltage sensors are in their most deactivated position. Consistently, a mutation that destabilizes these deactivated states is shown to largely suppress the first component in voltage-activation curves for both ΔPASCap and E600R channels.

The authors then address the role of the hidden O1 state in channel regulation by calmodulation. Stimulating calcium entry into oocytes with ionomycin and thapsigarging, assumed to enhance CaM-dependent modulation, resulted in preferential potentiation of the first component in ΔPASCap and E600R channels. This potentiation was attenuated by including an additional mutation that disfavors deeply closed states. Together, these results are interpreted as an indication that calcium-CaM preferentially stabilizes deeply closed states from which O1 can be readily accessed in mutant channels, thus favoring current activation. In WT channels lacking a conducting O1 state, CaM stabilizes deeply closed states and is therefore inhibitory. It is found that the potentiation of ΔPASCap and E600R by CaM is more strongly attenuated by mutations in the channel that are assumed to disrupt interaction with the C-terminal lobe of CaM than mutations assumed to affect interaction with the N-terminal lobe. These results are intriguing but difficult to interpret in mechanistic terms. The strong effect that calcium-CaM had on the occupancy of the O1 state in the mutants raises the possibility that O1 can be only observed in channels that are constitutively associated with CaM. To address this, a biochemical pull-down assay was carried out to establish that only a small fraction of channels are associated with CaM under baseline conditions. These CaM experiments are potentially very interesting and could have wide physiological relevance. However, the approach utilized to activate CaM is indirect and could result in additional nonspecific effects on the oocytes that could affect the results.

Finally, a mathematical model is proposed consisting of two layers involving two activation steps for the voltage sensor, and one conformational change in the cytoplasmic gating ring - completion of both sets of conformational changes is required to access state O2, but accessing state O1 only requires completion of the first voltage-sensor activation step in the four subunits. The model qualitatively reproduces most major findings on the mutants. Although the model used is highly symmetric and appears simple, the mathematical form used for the rate constants in the model adds a layer of complexity to the model that makes mechanistic interpretations difficult. In addition, many transitions that from a mechanistic standpoint should not depend on voltage were assigned a voltage dependence in the model. These limitations diminish the overall usefulness of the model which is prominently presented in the manuscript. The most important mechanistic assumptions in the model are not addressed experimentally, such as the proposition that entry into O1 depends on the opening of the transmembrane pore gate, whereas entry into O2 involves gating ring transitions - it is unclear why O2 would require further gating ring transitions to conduct ions given that the gating ring can already support permeation by O1 without any additional conformational changes.

In essence, we agree with the reviewer; we already have addressed these points in our revised article:

Regarding the voltage dependence we write “the κ/λ transition could reasonably be expected to be voltage independent because we related it to ring reconfiguration, a process that should occur as a consequence of a prior VSD transition. We have made some attempts to treat this transition as voltage independent but state-specific with upper-layer bias for states on the right and lower-layer bias for states on the left. This is in principle possible, as can already be gleaned from the similar voltage ranges of the left-right transition (α/β) and the κL/λ transition. However, this approach leads to a much larger number of free, less well constrained kinetic parameters and drastically complicated the parameter search. ” As you can see, we also formulated a strategy to free the model of the potentially spurious voltage dependence and (in bold here) explained why we did not follow this route in this study.

Regarding the need for gating ring transitions after O1, we wrote, “Thus, the underlying gating events can be separated into two steps: The first gating step involves only the voltage sensor without engaging the ring and leads to a pre-open state, which is non-conducting in the WT but conducting in our mutants. The second gating event operates at higher depolarizations, involves a change in the ring, and leads to an open state both in WT and in the mutants. ”

We interpret your statements such that you expect the conducting state to remain available once O1 is reached. However, the experimental evidence speaks against that the pore availability remains regardless of the further gating steps beyond O1. The description of model construction is informative here: “... we could exclude many possible [sites at which O1 connects to closed states] because the attachment site must be sufficiently far away from the conventional open state [O2]. Otherwise, the transition from "O1 preferred" to "O2 preferred" via a few closed intermediate states is very gradual and never produces the biphasic GV curves [that we observed]. ”

In other words, voltage-dependent gating steps beyond the state that offers access to O1 appear to close the pore, after it was open. That might occur because only then (for states in which at least one voltage sensor exceeded the intermediate position) the ring is fixed in a particular state until all sensors completed activation. In the WT, closing the pore in deactivated states might rely on an interaction that is absent in the mutant because, at least in HERG: “the interaction between the PAS domain and the C-terminus is more stable in closed than in open KV11.1 (HERG) channels, and a single chain antibody binding to the interface between PAS domain and CNBHD can access its epitope in open but not in closed channels, strongly supporting a change in conformation of the ring during gating ”

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In the present manuscript, Abdelaziz and colleagues interrogate the gating mechanisms of Kv10.1, an important voltage-gated K+ channel in cell cycle and cancer physiology. At the molecular level, Kv10.1 is regulated by voltage and Ca-CaM. Structures solved using CryoEM for Kv10.1 as well as other members of the KCNH family (Kv11 and Kv12) show channels that do not contain a structured S4-S5 linker imposing therefore a non-domain swapped architecture in the transmembrane region. However, the cytoplasmatic N- and C- terminal domains interact in a domain swapped manner forming a gating ring. The N-terminal domain (PAS domain) of one subunit is located close to the intracellular side of the voltage sensor domain and interacts with the C-terminal domain (CNBHD domain) of the neighbor subunit. Mutations in the intracellular domains has a profound effect in the channel gating. The complex network of interactions between the voltage-sensor and the intracellular domains makes the PAS domain a particularly interesting domain of the channel to study as responsible for the coupling between the voltage sensor domains and the intracellular gating ring.

The coupling between the voltage-sensor domain and the gating ring is not fully understood and the authors aim to shed light into the details of this mechanism. In order to do that, they use well established techniques such as site-directed mutagenesis, electrophysiology, biochemistry and mathematical modeling. In the present work, the authors propose a two open state model that arises from functional experiments after introducing a deletion on the PAS domain (ΔPAS Cap) or a point mutation (E600R) in the CNBHD domain. The authors measure a bi-phasic G-V curve with these mutations and assign each phase as two different open states, one of them not visible on the WT and only unveiled after introducing the mutations.

The hypothesis proposed by the authors could change the current paradigm in the current understanding for Kv10.1 and it is quite extraordinary; therefore, it requires extraordinary evidence to support it.

STRENGTHS: The authors use adequate techniques such as electrophysiology and sitedirected mutagenesis to address the gating changes introduced by the molecular manipulations. They also use appropriate mathematical modeling to build a Markov model and identify the mechanism behind the gating changes.

WEAKNESSES: The results presented by the authors do not fully support their conclusions since they could have alternative explanations. The authors base their primary hypothesis on the bi-phasic behavior of a calculated G-V curve that do not match the tail behavior, the experimental conditions used in the present manuscript introduce uncertainties, weakening their conclusions and complicating the interpretation of the results. Therefore, their experimental conditions need to be revisited.

We respectfully disagree. We think that your suggestions for alternative explanations are addressed in the current version of the article. We will rebut them once more below, but we feel the need to point out that our arguments are already laid out in the revised article.

I have some concerns related to the following points:

(1) Biphasic gating behavior

The authors use the TEVC technique in oocytes extracted surgically from Xenopus Leavis frogs. The method is well established and is adequate to address ion channel behavior. The experiments are performed in chloride-based solutions which present a handicap when measuring outward rectifying currents at very depolarizing potentials due to the presence of calcium activated chloride channel expressed endogenously in the oocytes; these channels will open and rectify chloride intracellularly adding to the outward rectifying traces during the test pulse. The authors calculate their G-V curves from the test pulse steady-state current instead of using the tail currents. The conductance measurements are normally taken from the 'tail current' because tails are measured at a fix voltage hence maintaining the driving force constant.

We respectfully disagree. In contrast to other channels, like HERG, a common practice for Kv10 is not to use tail currents. It is long known that in this channel, tail currents and test-pulse steady-state currents can appear to be at odds because the channels deactivate extremely rapidly, at the border of temporal resolution of the measurements and with intricate waveforms. This complicates the estimation of the instantaneous tail current. Therefore, the outward current is commonly used to estimate conductance (Terlau et al., 1996; Schönherr et al., 1999; Schönherr et al., 2002; Whicher and MacKinnon, 2019), while the latter authors also use the extreme of the tail for some mutants.

Due to their activation at very negative voltage, the reversal potential in our mutants can be measured directly; we are, therefore, more confident with this approach. Nevertheless, we have determined the initial tail current in some experiments. The behavior of these is very similar to the average that we present in Figure 1. The biphasic behavior is unequivocally present.

Author response image 2.

Calculating the conductance from the traces should not be a problem, however, in the present manuscript, the traces and the tail currents do not agree.

The referee’s observation is perfectly in line with the long-standing experience of several labs working with KV10: tail current amplitudes in KV10 appear to be out of proportion for the WT open state (O2). Importantly, this is due to the rapid closure, which is not present in O1. As a consequence, the initial amplitude of tail currents from O1 are easier to estimate correctly, and they are much more obvious in the graphs. Taken together, these differences between O1 and O2 explain the misconception the reviewer describes next.

The tail traces shown in Fig1E do not show an increasing current amplitude in the voltage range from +50mV to +120mV, they seem to have reached a 'saturation state', suggesting that the traces from the test pulse contain an inward chloride current contamination.

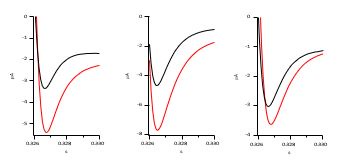

As stated in the text and indicated in Author response image 3, the tail currents In Figure 1E increase in amplitude between +50 and +120 mV, as can be seen in the examples below from different experiments (+50 is presented in black, +120 in red). As stated above, the increase is not as evident as in traces from other mutants because the predominance of O2 also implies a much faster deactivation.

Author response image 3.

We are aware that Ca2+-activated Cl- currents can represent a problem when interpreting electrophysiological data in oocytes. In fact, we show in Supplement 1 to Figure 8 that this can be the case during the Ca2+-CaM experiments, where the increase in Ca2+ would certainly augment Cl- contribution to the outward current. This is why we performed these experiments in Cl--free solutions. As we show in Figure 8, the biphasic behavior was also present in those experiments.

Importantly, Cl- free bath solutions would not correct contamination during the tail, since this would correspond to Cl- exiting the oocyte. Yet, if there would be contamination of the outward currents by Cl-, one would expect it to increase with larger depolarizations as the typical Ca2+activated Cl- current in oocytes does. As the reviewer states, this does not seem to be the case.

In addition, this second component identified by the authors as a second open state appears after +50mV and seems to never saturate. The normalization to the maximum current level during the test pulse, exaggerates this second component on the calculated G-V curve.

We agree that this second component continues to increase; the reviewer brought this up in the first review, and we have already addressed this in our reply and in the discussion of the revised version: “This flicker block might also offer an explanation for a feature of the mutant channels, that is not explained in the current model version: the continued increase in current amplitude, hundreds of milliseconds into a strong depolarization (Supp. 4 to Fig. 9). If the relative stability of O2 and C2 continued to change throughout depolarization, such a current creep-up could be reproduced. However, this would require either the introduction of further layers of On ↔Cn states, or a non-Markovian modification of the model’s time evolution.” With non-Markovian, we mean a Langevin-type diffusive process.

It's worth noticing that the ΔPASCap mutant experiments on Fig 5 in Mes based solutions do not show that second component on the G-V.

For the readers of this conversation, we would like to clarify that the reviewer likely refers to experiments shown in Fig. 5 of the initial submission but shown in Fig. 6 of the revised version (“Hyperpolarization promotes access to a large conductance, slowly activating open state.” Fig. 5 deals with single channels). We agree that these data look different, but this is because the voltage protocols are completely different (compare Fig. 6A (fixed test pulse, varied prepulse) and Fig. 2A (varied test pulse, fixed pre-pulse). Therefore, no biphasic behavior is expected.

Because these results are the foundation for their two open state hypotheses, I will strongly suggest the authors to repeat all their Chloride-based experiments in Mes-based solutions to eliminate the undesired chloride contribution to the mutants current and clarify the contribution of the mutations to the Kv10.1 gating.

In summary, we respectfully disagree with all concerns raised in point (1). Our detailed arguments rebutting them are given above, but there is a more high-level concern about this entire exchange: the referee casts doubt on observations that are not new. Several labs have reported for a group of mutant KCNH channels: non-monotonic voltage dependence of activation (see, e.g., Fig. 6D in Zhao et al., 2017), multi-phasic tail currents (see e.g. Fig. 4A in Whicher and MacKinnon, 2019, in CHO cells where Cl- contamination is not a concern), and activation by high [Ca2+]i (Lörinczi et al., 2016). Our study replicates those observations and hypothesizes that the existence of an additional conducting state can alone explain all previously unexplained observations. We highlight the potency of this hypothesis with a Markov model that qualitatively reproduces all phenomena. We not only factually disagree with the individual points raised, but we also think that they don't touch on the core of our contribution

(2) Two step gating mechanism.

The authors interpret the results obtained with the ΔPASCap and the E600R as two step gating mechanisms containing two open states (O1 and O2) and assign them to the voltage sensor movement and gating ring rotation respectively. It is not clear, however how the authors assign the two open states.

The results show how the first component is conserved amongst mutations; however, the second one is not. The authors attribute the second component, hence the second open state to the movement of the gating ring. This scenario seems unlikely since there is a clear voltagedependence of the second component that will suggest an implication of a voltage-sensing current.

We do not suggest that the gating ring motion is not voltage dependent. We would like to point out that voltage dependence can be conveyed by voltage sensor coupling to the ring; this is the widely accepted theory of how the ring can be involved. Should the reviewer mean it in a narrow sense, that the model should be constructed such that all voltage-dependent steps occur before and independently of ring reconfiguration and that only then an additional step that reflects the (voltage-independent) reconfiguration solely, we would like to point the reviewer to the article, where we write: “the κ/λ transition could reasonably be expected to be voltage independent because we related it to ring reconfiguration, a process that should occur as a consequence of a prior VSD transition. We have made some attempts to treat this transition as voltage independent but state-specific with upper-layer bias for states on the right and lower-layer bias for states on the left. This is in principle possible, as can already be gleaned from the similar voltage ranges of the left-right transition (α/β) and the κL/λ transition. However, this approach leads to a much larger number of free, less well constrained kinetic parameters and drastically complicated the parameter search. ” As you can see, we also formulated a strategy to free the model from the potentially spurious voltage dependence and (in bold here) explained why we did not follow this route in this study.

The split channel experiment is interesting but needs more explanation. I assume the authors expressed the 2 parts of the split channel (1-341 and 342-end), however Tomczak et al showed in 2017 how the split presents a constitutively activated function with inward currents that are not visible here, this point needs clarification.

As stated in the panel heading, the figure legend, and the main text, we did not use 1-341 and 342-end as done in Tomczak et al. Instead, “we compared the behavior of ∆2-10 and ∆210.L341Split,”. Evidently, the additional deletion (2-10) causes a shift in activation that explains the difference you point out. However, as we do not compare L341Split and ∆210.L341Split but ∆2-10 and ∆2-10.L341Split, our conclusion remains that “As predicted, compared to ∆2-10, ∆2-10.L341Split showed a significant reduction in the first component of the biphasic GV (Fig. 2C, D).” Remarkably, the behavior of the ∆3-9 L341Split described in Whicher and MacKinnon, 2019 (Figure 5) matches that of our ∆2-10 L341Split, which we think reinforces our case.

Moreover, the authors assume that the mutations introduced uncover a new open state, however the traces presented for the mutations suggest that other explanations are possible. Other gating mechanisms like inactivation from the closed state, can be introduced by the mutations. The traces presented for ΔPASCap but specially E600R present clear 'hooked tails', a direct indicator of a populations of inactive channels during the test pulse that recover from inactivation upon repolarization (Tristani-Firouzi M, Sanguinetti MC. J Physiol. 1998).

There is a possibility that we are debating nomenclature here. In response to the suggestion that all our observations could be explained by inactivation, we attempted a disambiguation of terms in the reply and the article. As the argument is brought up again without reference to our clarification attempts, we will try to be more explicit here:

If, starting from deeply deactivated states, an open state is reached first, and then, following further activation steps, closed states are reached, this might be termed “inactivation”. In such a reading, our model features many inactivated states. The shortest version of such a model is C-O-I. It is for instance used by Raman and Bean (2001; DOI: 10.1016/S00063495(01)76052-3) to explain NaV gating in Purkinje neurons. If “inactivation” is meant in the sense that a gating transition exists, which is orthogonal to an activation/deactivation axis, and that after this orthogonal transition, an open state cannot be reached anymore, then all of the upper floor in our model is inactivated with respect to the open state O1. Finally, the state C2 is an inactivated state to O2. In this view, “inactivation” explains the observed phenomena.

However, we must disagree if the referee means that a parsimonious explanation exists in which a single conducting state is the only source for all observed currents.

There is a high-level reason: we found a single assumption that explains three different phenomena, while the inactivation hypothesis with one conducting state cannot explain one of them (the increase of the first component under raised CaM). But there is also a low-level reason: the tails in Tristani-Firouzi and Sanguinetti 1998 are fundamentally different from what we report herein in that they lack a third component. Thus, those tails are consistent with recovery from inactivation through a single open state, while a three-component tail is not. In the framework of a Markov model, the time constants of transitions from and to a given state (say O2), cannot change unless the voltage changes. During the tail current, the voltage does not change, yet we observe:

i) a rapid decrease with a time constant of at most a few milliseconds (Fig 9 S2, 1-> 2), ii) a slow increase in current, peaking after approximately 25 milliseconds and iii) a relaxation to zero current with a time constant of >50 ms.

According to the reviewer’s suggestion, these processes on three timescales should all be explained by depopulating and repopulating the same open state while all rates are constant. There might well be a complicated multi-level state diagram with a single open state with different variants, like (open and open inactivated) that could produce triphasic tails with these properties if the system had not reached a steady state distribution at the end of the test pulse. It cannot, however, achieve it from an equilibrated system, and certainly, it cannot at the same time produce “biphasic activation” and “activation by CaM”.

The results presented by the authors can be alternatively explained with a change in the equilibrium between the close to inactivated/recovery from inactivation to the open state.

Again, we disagree. The model construction explains in detail that the transition from the first to the second phase is not gradual. Shifting equilibria cannot reproduce this. We have extensively tested that idea and can exclude this possibility.

Finally, the authors state that they do not detect "cumulative inactivation after repeated depolarization" but that is considering inactivation only from the open state and ignoring the possibility of the existence of close state inactivation or, that like in hERG, that the channel inactivates faster that what it activates (Smith PL, Yellen G. J Gen Physiol. 2002).

We respectfully disagree. We explicitly model an open state that inactivates faster (O2->C2) than it activates. Once more, this is stated in the revised article, which we point to for details. Again, this alternative mechanism does not have the potential to explain all three effects. As discussed above about the chloride contamination concerns, this inactivation hypothesis was mentioned in the first review round and, therefore, addressed in our reply and the revised article. We also explained that “inactivation” has no specific meaning in Markov models. In the absence of O1, all transitions towards the lower layer are effectively “inactivation from closed states”, because they make access to the only remaining open state less likely”. But this is semantics. What is relevant is that no network of states around a single open state can reproduce the three effets in a more parsimonious way than the assumption of the second open state does.

(3) Single channel conductance.

The single channels experiments are a great way to assess the different conductance of single channel openings, unfortunately the authors cannot measure accurately different conductances for the two proposed open states. The Markov Model built by the authors, disagrees with their interpretation of the experimental results assigning the exact same conductance to the two modeled open states. To interpret the mutant data, it is needed to add data with the WT for comparison and in presence of specific blockers.

We respectfully disagree. As previously shown, the conductance of the flickering wild-type open state is very difficult to resolve. Our recordings do not show that the two states have different single-channel conductances, and therefore the model assumes identical singlechannel conductance.

The important point is that the single-channel recordings clearly show two different gating modes associated with the voltage ranges in which we predict the two open states. One has a smaller macroscopic current due to rapid flickering (aka “inactivation”). These recordings are another proof of the existence of two open states because the two gating modes occur. Wild-type data can be found in Bauer and Schwarz, (2001, doi:10.1007/s00232-001-0031-3) or Pardo et al., (1998, doi:10.1083/jcb.143.3.767) for comparison.

We appreciate the effort editors and reviewers invested in assessing the revised manuscript. Yet, we think that the demanded revision of experimental conditions and quantification methods contradicts the commonly accepted practice for KV10 channels. Some of the reviewer comments are skeptical about the biphasic behavior, which is an established and replicated finding for many mutants and by many researchers. The alternative explanations for these disbelieved findings are either “semantics” or cannot quantitatively explain the measurements. Therefore, only the demand for more explanations and unprecedented resolution in singlechannel recordings remains. We share these sentiments.

———— The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

(1) The authors must show that the second open state is not just an artifact of endogenous activity but represents the activity of the same EAG channels. I suggest that the authors repeat these experiments in Mes-based solutions.

(2) Along the same lines, it is necessary to show that these currents can be blocked using known EAG channel blockers such as astemizole. Ultimately, it will be important to demonstrate using single-channel analysis that these do represent two distinct open states separated by a closed state.

We have addressed these concerns using several approaches. The most substantial change is the addition of single-channel recordings on ΔPASCap. In those experiments, we could provide evidence of the two types of events in the same patch, and the presence of an outward current at -60 mV, 50 mV below the equilibrium potential for chloride. The channels were never detected in uninjected oocytes, and Astemizole silenced the activity in patches containing multiple channels. These observations, together with the maintenance of the biphasic behavior that we interpret as evidence of the presence of O1 in methanesulfonate-based solutions, strongly suggest that both O1 and O2 obey the expression of KV10.1 mutants.

(3) Currents should be measured by increasing the pulse lengths as needed in order to obtain the true steady-state G-V curves.

We agree that the endpoint of activation is ill-defined in the cases where a steady-state is not reached. This does indeed hamper quantitative statements about the relative amplitude of the two components. However, while the overall shape does change, its position (voltage dependence) would not be affected by this shortcoming. The data, therefore, supports the claim of the “existence of mutant-specific O1 and its equal voltage dependence across mutants.”

(4) A more clear and thorough description should be provided for how the observations with the mutant channels apply to the behavior of WT channels. How exactly does state O1 relate to WT behavior, and how exactly do the parameters of the mathematical model differ between WT and mutants? How can this be interpreted at a structural level? What could be the structural mechanism through which ΔPASCap and E600R enable conduction through O1? It seems contradictory that O1 would be associated exclusively with voltage-sensor activation and not gating ring transitions, and yet the mutations that enable cation access through O1 localize at the gating ring - this needs to be better clarified.

We have undertaken a thorough rewriting of all sections to clarify the structural correlates that may explain the behavior of the mutants. In brief, we propose that when all four voltage sensors move towards the extracellular side, the intracellular ring maintains the permeation path closed until it rotates. If the ring is altered, this “lock” is incompetent, and permeation can be detected (page 34). By fixing the position of the ring, calmodulin would preclude permeation in the WT and promote the population of O1 in the mutants.

(5) Rather than the t80% risetime, exponential fits should be performed to assess the kinetics of activation.

We agree that the assessment of kinetics by a t80% is not ideal. We originally refrained from exponential fits because they introduce other issues when used for processes that are not truly exponential (as is the case here). We had planned to perform exponential fits in this revised version, but because the activation process is not exponential, the time constants we could provide would not be accurate, and the result would remain qualitative as it is now. In the experiments where we did perform the fits (Fig. 3), the values obtained support the statement made.

(6) It is argued based on the G-V relations in Figure 2A that none of the mutations or deletions introduced have a major effect on state O1 properties, but rather affect state O2. However, the occupancy of state O2 is undetermined because activation curves do not reach saturation. It would be interesting to explore the fitting parameters on Fig.2B further to test whether the data on Fig 2A can indeed only be described by fits in which the parameters for O1 remain unchanged between constructs.

We agree that the absolute occupancy of O2 cannot be properly determined if a steady state is not reached. This is, however, a feature of the channel. During very long depolarizations in WT, the current visually appears to reach a plateau, but a closer look reveals that the current keeps increasing after very long depolarizations (up to 10 seconds; see, e.g., Fig. 1B in Garg et al., 2013, Mol Pharmacol 83, 805-813. DOI: 10.1124/mol.112.084384). Interestingly, although the model presented here does not account for this behavior, we propose changes in the model that could. “If the relative stability of O2 and C2 continued to change throughout the depolarization such a current creep-up could be reproduced. However, this would require either the introduction of further layers of On↔Cn states or a non-Markovian modification of the model’s evolution.” Page 34.

(7) The authors interpret the results obtained with the mutants DPASCAP and E600R -tested before by Lorinczi et al. 2016, to disrupt the interactions between the PASCap and cNBHD domains- as a two-step gating mechanism with two open states. All the results obtained with the E600R mutant and DPASCap could also be explained by inactivation/recovery from inactivation behavior and a change in the equilibrium between the closed states closed/inactivated states and open states. Moreover, the small tails between +90 to +120 mV suggest channels accumulate in an inactive state (Fig 1E). It is not convincing that the two open-state model is the mechanism underlying the mutant's behavior.