Cortical tracking of hierarchical rhythms orchestrates the multisensory processing of biological motion

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

eLife Assessment

Wang et al. presented visual (dot) motion and/or the sound of a walking person and found solid evidence that EEG activity tracks the step rhythm, as well as the gait (2-step cycle) rhythm, with some demonstration that the gait rhythm is tracked superadditively (power for A+V condition is higher than the sum of the A-only and V-only condition). The valuable findings will be of wide interest to those examining biological motion perception and oscillatory processes more broadly.

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

When observing others’ behaviors, we continuously integrate their movements with the corresponding sounds to enhance perception and develop adaptive responses. However, how the human brain integrates these complex audiovisual cues based on their natural temporal correspondence remains unclear. Using electroencephalogram (EEG), we demonstrated that rhythmic cortical activity tracked the hierarchical rhythmic structures in audiovisually congruent human walking movements and footstep sounds. Remarkably, the cortical tracking effects exhibit distinct multisensory integration modes at two temporal scales: an additive mode in a lower-order, narrower temporal integration window (step cycle) and a super-additive enhancement in a higher-order, broader temporal window (gait cycle). Furthermore, while neural responses at the lower-order timescale reflect a domain-general audiovisual integration process, cortical tracking at the higher-order timescale is exclusively engaged in the integration of biological motion cues. In addition, only this higher-order, domain-specific cortical tracking effect correlates with individuals’ autistic traits, highlighting its potential as a neural marker for autism spectrum disorder. These findings unveil the multifaceted mechanism whereby rhythmic cortical activity supports the multisensory integration of human motion, shedding light on how neural coding of hierarchical temporal structures orchestrates the processing of complex, natural stimuli across multiple timescales.

Article activity feed

-

-

eLife Assessment

Wang et al. presented visual (dot) motion and/or the sound of a walking person and found solid evidence that EEG activity tracks the step rhythm, as well as the gait (2-step cycle) rhythm, with some demonstration that the gait rhythm is tracked superadditively (power for A+V condition is higher than the sum of the A-only and V-only condition). The valuable findings will be of wide interest to those examining biological motion perception and oscillatory processes more broadly.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Shen et al. conducted three experiments to study the cortical tracking of the natural rhythms involved in biological motion (BM), and whether these involve audiovisual integration (AVI). They presented participants with visual (dot) motion and/or the sound of a walking person. They found that EEG activity tracks the step rhythm, as well as the gait (2-step cycle) rhythm. The gait rhythm specifically is tracked superadditively (power for A+V condition is higher than the sum of the A-only and V-only condition, Experiments 1a/b), which is independent of the specific step frequency (Experiment 1b). Furthermore, audiovisual integration during tracking of gait was specific to BM, as it was absent (that is, the audiovisual congruency effect) when the walking dot motion was vertically inverted (Experiment 2). …

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Shen et al. conducted three experiments to study the cortical tracking of the natural rhythms involved in biological motion (BM), and whether these involve audiovisual integration (AVI). They presented participants with visual (dot) motion and/or the sound of a walking person. They found that EEG activity tracks the step rhythm, as well as the gait (2-step cycle) rhythm. The gait rhythm specifically is tracked superadditively (power for A+V condition is higher than the sum of the A-only and V-only condition, Experiments 1a/b), which is independent of the specific step frequency (Experiment 1b). Furthermore, audiovisual integration during tracking of gait was specific to BM, as it was absent (that is, the audiovisual congruency effect) when the walking dot motion was vertically inverted (Experiment 2). Finally, the study shows that an individual's autistic traits are negatively correlated with the BM-AVI congruency effect.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

The authors evaluate spectral changes in electroencephalography (EEG) data as a function of the congruency of audio and visual information associated with biological motion (BM) or non-biological motion. The results show supra-additive power gains in the neural response to gait dynamics, with trials in which audio and visual information was presented simultaneously producing higher average amplitude than the combined average power for auditory and visual conditions alone. Further analyses suggest that such supra-additivity is specific to BM and emerges from temporoparietal areas. The authors also find that the BM-specific supra-additivity is negatively correlated with autism traits.

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

Shen et al. conducted three experiments to study the cortical tracking of the natural rhythms involved in biological motion (BM), and whether these involve audiovisual integration (AVI). They presented participants with visual (dot) motion and/or the sound of a walking person. They found that EEG activity tracks the step rhythm, as well as the gait (2-step cycle) rhythm. The gait rhythm specifically is tracked superadditively (power for A+V condition is higher than the sum of the A-only and V-only condition,

Experiments 1a/b), which is independent of the specific step frequency (Experiment 1b). Furthermore, audiovisual integration during tracking of gait was specific to BM, as it was absent (that is, …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

Shen et al. conducted three experiments to study the cortical tracking of the natural rhythms involved in biological motion (BM), and whether these involve audiovisual integration (AVI). They presented participants with visual (dot) motion and/or the sound of a walking person. They found that EEG activity tracks the step rhythm, as well as the gait (2-step cycle) rhythm. The gait rhythm specifically is tracked superadditively (power for A+V condition is higher than the sum of the A-only and V-only condition,

Experiments 1a/b), which is independent of the specific step frequency (Experiment 1b). Furthermore, audiovisual integration during tracking of gait was specific to BM, as it was absent (that is, the audiovisual congruency effect) when the walking dot motion was vertically inverted (Experiment 2). Finally, the study shows that an individual's autistic traits are negatively correlated with the BM-AVI congruency effect.

Strengths:

The three experiments are well designed and the various conditions are well controlled. The rationale of the study is clear, and the manuscript is pleasant to read. The analysis choices are easy to follow, and mostly appropriate.

Weaknesses:

On revision, the authors are careful not to overinterpret an analysis where the statistical test is not independent from the data (channel) selection criterion.

Thanks for the suggestion and we have done this according to your recommendations below.

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for the authors):

Re: the double-dipping concern: I appreciate the revision. Just to clarify: my concern rests with the selection of *electrodes* based on the interaction test for the 1Hz condition. The 2Hz condition analogous test yields no significant electrodes. You perform subsequent tests (t-tests and 3-way interaction) on the data averaged across the electrodes that were significant for the 1Hz condition. Therefore, these tests will be biased to find a pattern reflecting an interaction at 1Hz, while no similar bias exists for an effect at 2Hz. Therefore, there is a bias to observe a 3-way interaction, and simple effects compatible with a 2-way interaction only for 1Hz, not for 2Hz (which is exactly what you found). There is no good statistical alternative here, I appreciate that, but the bias exists nonetheless. I think the wording is improved in this revision, and the evidence is convincing even in light of this bias.

We are grateful for your thoughtful comments on the analytical methods. We appreciate your concerns regarding the potential bias of examining 3-way interaction based on electrodes yielding a 2-way interaction effect. To address this issue, we have conducted a bias-free analysis based on electrodes across the whole brain. The results showed a similar pattern of 3-way interaction as previously reported (p = 0.051), suggesting that the previous findings might not be caused by electrode selection. Given that the main results of Experiment 2 were not based on whole-brain analysis, we did not involve this analysis in the main text, and we have removed the three-way interaction results based on selected electrodes from the manuscript to reduce potential concerns. It is also noteworthy that, when performing analyses based on channels independent of the interaction effect at 1 Hz (i.e., significant congruency effects in the upright and inverted conditions, respectively, at 2Hz), we got similar results as reported in the main text (i.e., non-significant interaction and correlation at 2 Hz). These results were presented in the supplementary file in previous versions and mentioned in the correlation part of the Results section (see Fig. S2). Once again, we sincerely appreciate your careful review of our research. We hope the abovementioned points adequately address your concern.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors evaluate spectral changes in electroencephalography (EEG) data as a function of the congruency of audio and visual information associated with biological motion (BM) or non-biological motion. The results show supra-additive power gains in the neural response to gait dynamics, with trials in which audio and visual information was presented simultaneously producing higher average amplitude than the combined average power for auditory and visual conditions alone. Further analyses suggest that such supra-additivity is specific to BM and emerges from temporoparietal areas. The authors also find that the BM-specific supra-additivity is negatively correlated with autism traits.

Strengths:

The manuscript is well-written, with a concise and clear writing style. The visual presentation is largely clear. The study involves multiple experiments with different participant groups. Each experiment involves specific considered changes to the experimental paradigm that both replicate the previous experiment's finding yet extend it in a relevant manner.

In the first revisions of the paper, the manuscript better relays the results and anticipates analyses, and this version adequately resolves some concerns I had about analysis details. In a further revision, it is clarified better how the results relate to the various competing hypotheses on how biological motion is processed.

Weaknesses:

Still, it is my view that the findings of the study are basic neural correlate results that offer only minimal constraint towards the question of how the brain realizes the integration of multisensory information in the service of biological motion perception, and the data do not address the causal relevance of observed neural effects towards behavior and cognition. The presence of an inversion effect suggests that the supraadditivity is related to cognition, but that leaves open whether any detected neural pattern is actually consequential for multi-sensory integration (i.e., correlation is not causation). In other words, the fact that frequency-specific neural responses to the [audio & visual] condition are stronger than those to [audio] and [visual] combined does not mean this has implications for behavioral performance. While the correlation to autism traits could suggest some relation to behavior and is interesting in its own right, this correlation is a highly indirect way of assessing behavioral relevance. It would be helpful to test the relevance of supra-additive cortical tracking on a behavioral task directly related to the processing of biological motion to justify the claim that inputs are being integrated in the service of behavior. Under either framework, cortical tracking or entrainment, the causal relevance of neural findings toward cognition is lacking.

Overall, I believe this study finds neural correlates of biological motion that offer some constraint toward mechanism, and it is possible that the effects are behaviorally relevant, but based on the current task and associated analyses this has not been shown (or could not have been, given the paradigm).

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors):

Thank you for your revisions; I have updated the Strengths section, and reworded the weaknesses section. I now concede that the neural effects observed offer some constraint towards what the neural mechanisms for AV integration for BM are, whereas in my previous review, I said too strongly that these results do not offer any information about mechanism.

Thank you again for your insightful thoughts and comments on our research. They have contributed greatly to enhancing the discussion of the article and provided valuable inspiration for future exploration of causal mechanisms.

-

-

-

eLife Assessment

Wang et al. presented visual (dot) motion and/or the sound of a walking person and found solid evidence that EEG activity tracks the step rhythm, as well as the gait (2-step cycle) rhythm, with some demonstration that the gait rhythm is tracked superadditively (power for A+V condition is higher than the sum of the A-only and V-only condition). The valuable findings will be of wide interest to those examining biological motion perception and oscillatory processes more broadly. Some of the theoretical interpretations concerning entrainment must remain speculative when the authors cannot dissociate evoked responses from entrained oscillatory effects.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

Shen et al. conducted three experiments to study the cortical tracking of the natural rhythms involved in biological motion (BM), and whether these involve audiovisual integration (AVI). They presented participants with visual (dot) motion and/or the sound of a walking person. They found that EEG activity tracks the step rhythm, as well as the gait (2-step cycle) rhythm. The gait rhythm specifically is tracked superadditively (power for A+V condition is higher than the sum of the A-only and V-only condition, Experiments 1a/b), which is independent of the specific step frequency (Experiment 1b). Furthermore, audiovisual integration during tracking of gait was specific to BM, as it was absent (that is, the audiovisual congruency effect) when the walking dot motion was vertically inverted (Experiment …

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

Shen et al. conducted three experiments to study the cortical tracking of the natural rhythms involved in biological motion (BM), and whether these involve audiovisual integration (AVI). They presented participants with visual (dot) motion and/or the sound of a walking person. They found that EEG activity tracks the step rhythm, as well as the gait (2-step cycle) rhythm. The gait rhythm specifically is tracked superadditively (power for A+V condition is higher than the sum of the A-only and V-only condition, Experiments 1a/b), which is independent of the specific step frequency (Experiment 1b). Furthermore, audiovisual integration during tracking of gait was specific to BM, as it was absent (that is, the audiovisual congruency effect) when the walking dot motion was vertically inverted (Experiment 2). Finally, the study shows that an individual's autistic traits are negatively correlated with the BM-AVI congruency effect.

Strengths:

The three experiments are well designed and the various conditions are well controlled. The rationale of the study is clear, and the manuscript is pleasant to read. The analysis choices are easy to follow, and mostly appropriate.

Weaknesses:

On revision, the authors are careful not to overinterpret an analysis where the statistical test is not independent from the data (channel) selection criterion.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors evaluate spectral changes in electroencephalography (EEG) data as a function of the congruency of audio and visual information associated with biological motion (BM) or non-biological motion. The results show supra-additive power gains in the neural response to gait dynamics, with trials in which audio and visual information was presented simultaneously producing higher average amplitude than the combined average power for auditory and visual conditions alone. Further analyses suggest that such supra-additivity is specific to BM and emerges from temporoparietal areas. The authors also find that the BM-specific supra-additivity is negatively correlated with autism traits.

Strengths:

The manuscript is well-written, with a concise and clear writing style. The visual presentation is largely …

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors evaluate spectral changes in electroencephalography (EEG) data as a function of the congruency of audio and visual information associated with biological motion (BM) or non-biological motion. The results show supra-additive power gains in the neural response to gait dynamics, with trials in which audio and visual information was presented simultaneously producing higher average amplitude than the combined average power for auditory and visual conditions alone. Further analyses suggest that such supra-additivity is specific to BM and emerges from temporoparietal areas. The authors also find that the BM-specific supra-additivity is negatively correlated with autism traits.

Strengths:

The manuscript is well-written, with a concise and clear writing style. The visual presentation is largely clear. The study involves multiple experiments with different participant groups. Each experiment involves specific considered changes to the experimental paradigm that both replicate the previous experiment's finding yet extend it in a relevant manner.

In the first revisions of the paper, the manuscript better relays the results and anticipates analyses, and this version adequately resolves some concerns I had about analysis details. In a further revision, it is clarified better how the results relate to the various competing hypotheses on how biological motion is processed.

Weaknesses:

Still, it is my view that the findings of the study are basic neural correlate results that offer only minimal constraint towards the question of how the brain realizes the integration of multisensory information in the service of biological motion perception, and the data do not address the causal relevance of observed neural effects towards behavior and cognition. The presence of an inversion effect suggests that the supra-additivity is related to cognition, but that leaves open whether any detected neural pattern is actually consequential for multi-sensory integration (i.e., correlation is not causation). In other words, the fact that frequency-specific neural responses to the [audio & visual] condition are stronger than those to [audio] and [visual] combined does not mean this has implications for behavioral performance. While the correlation to autism traits could suggest some relation to behavior and is interesting in its own right, this correlation is a highly indirect way of assessing behavioral relevance. It would be helpful to test the relevance of supra-additive cortical tracking on a behavioral task directly related to the processing of biological motion to justify the claim that inputs are being integrated in the service of behavior. Under either framework, cortical tracking or entrainment, the causal relevance of neural findings toward cognition is lacking.

Overall, I believe this study finds neural correlates of biological motion that offer some constraint toward mechanism, and it is possible that the effects are behaviorally relevant, but based on the current task and associated analyses this has not been shown (or could not have been, given the paradigm).

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

Shen et al. conducted three experiments to study the cortical tracking of the natural rhythms involved in biological motion (BM), and whether these involve audiovisual integration (AVI). They presented participants with visual (dot) motion and/or the sound of a walking person. They found that EEG activity tracks the step rhythm, as well as the gait (2-step cycle) rhythm. The gait rhythm specifically is tracked superadditively (power for A+V condition is higher than the sum of the A-only and V-only condition, Experiments 1a/b), which is independent of the specific step frequency (Experiment 1b). Furthermore, audiovisual integration during tracking of gait was specific to BM, as it was absent (that is, …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

Shen et al. conducted three experiments to study the cortical tracking of the natural rhythms involved in biological motion (BM), and whether these involve audiovisual integration (AVI). They presented participants with visual (dot) motion and/or the sound of a walking person. They found that EEG activity tracks the step rhythm, as well as the gait (2-step cycle) rhythm. The gait rhythm specifically is tracked superadditively (power for A+V condition is higher than the sum of the A-only and V-only condition, Experiments 1a/b), which is independent of the specific step frequency (Experiment 1b). Furthermore, audiovisual integration during tracking of gait was specific to BM, as it was absent (that is, the audiovisual congruency effect) when the walking dot motion was vertically inverted (Experiment 2). Finally, the study shows that an individual's autistic traits are negatively correlated with the BM-AVI congruency effect.

Strengths:

The three experiments are well designed and the various conditions are well controlled. The rationale of the study is clear, and the manuscript is pleasant to read. The analysis choices are easy to follow, and mostly appropriate.

Weaknesses:

There is a concern of double-dipping in one of the tests (Experiment 2, Figure 3: interaction of Upright/Inverted X Congruent/Incongruent). I raised this concern on the original submission, and it has not been resolved properly. The follow-up statistical test (after channel selection using the interaction contrast permutation test) still is geared towards that same contrast, even though the latter is now being tested differently. (Perhaps not explicitly testing the interaction, but in essence still testing the same.) A very simple solution would be to remove the post-hoc statistical tests and simply acknowledge that you're comparing simple means, while the statistical assessment was already taken care of using the permutation test. (In other words: the data appear compelling because of the cluster test, but NOT because of the subsequent t-tests.)

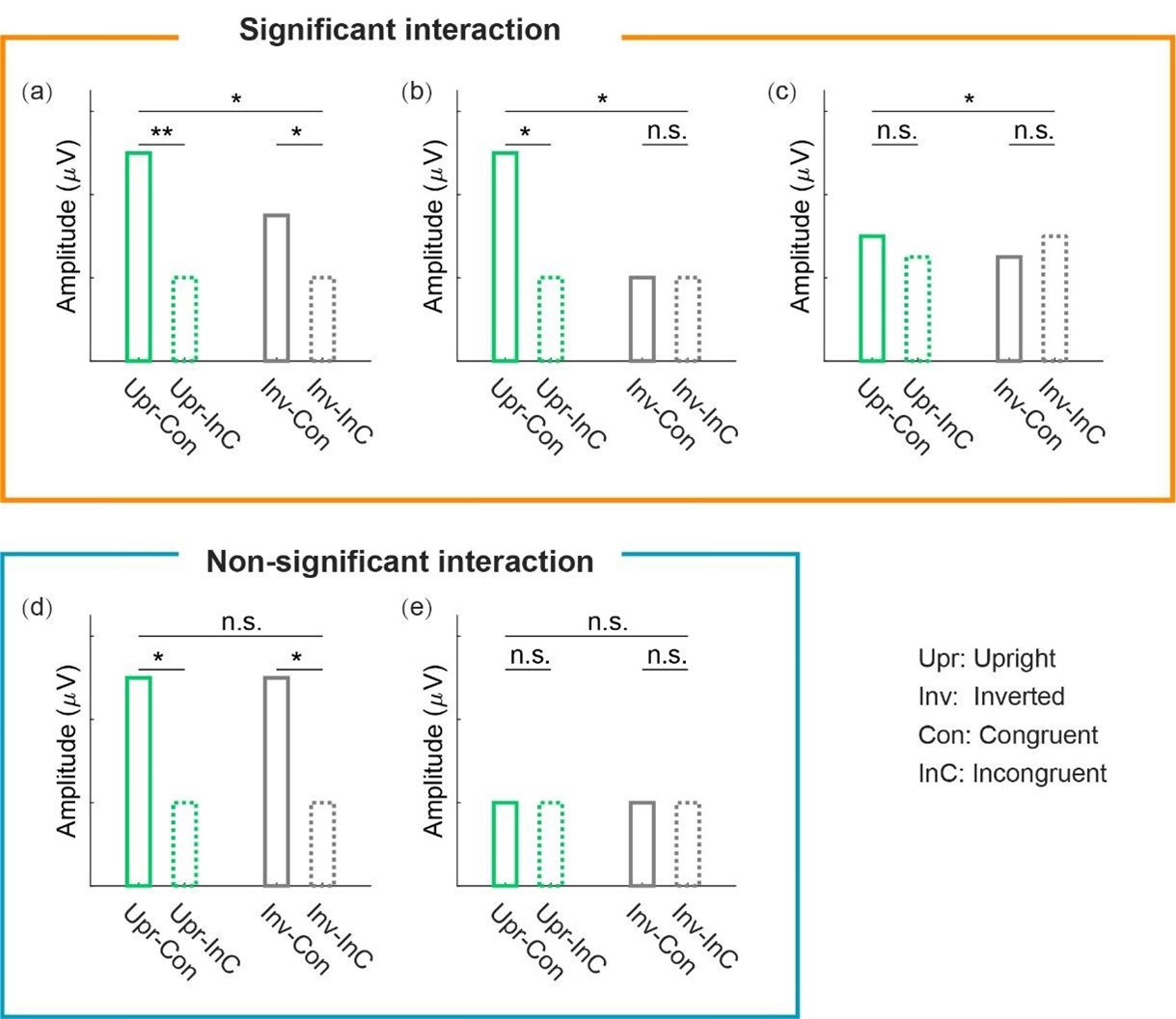

We are sorry that we did not explain this issue clearly before, which might have caused some misunderstanding. When performing the cluster-based permutation test, we only tested whether the audiovisual congruency effect (congruent vs. incongruent) between the upright and inverted conditions was significantly different [i.e., (UprCon – UprInc) vs. (InvCon – InvInc)], without conducting extra statistical analyses on whether the congruency effect was significant in each orientation condition. Such an analysis yielded a cluster with a significant interaction between audiovisual integration and BM orientation for the cortical tracking effect at 1Hz (but not at 2Hz). However, this does not provide valid information about whether the audiovisual congruency effect at this cluster is significant in each orientation condition, given that a significant interaction effect may result from various patterns of data across conditions: such as significant congruency effects in both orientation conditions (Author response image 1a), a significant congruency effect in the upright condition and a non-significant effect in the inverted condition (Author response image 1b), or even non-significant yet opposite effects in the two conditions (Author response image 1c). Here, our results conform to the second pattern, indicating that cortical tracking of the high-order gait cycles involves a domain-specific process exclusively engaged in the AVI of BM. In a similar vein, the non-significant interaction found at 2Hz does not necessarily indicate that the congruency effect is non-significant in each orientation condition (Author response image 1f&e). Indeed, the congruency effect was significant in both the upright and inverted conditions at 2Hz in our study despite the non-significant interaction, suggesting that neural tracking of the lower-order step cycles is associated with a domain-general AVI process mostly driven by temporal correspondence in physical stimuli.

Therefore, we need to perform subsequent t-tests to examine the significance of the simple effects in the two orientation conditions, which do not duplicate the clusterbased permutation test (for interaction only) and cause no double-dipping. Results from interaction and simple effects, put together, provide solid evidence that the cortical tracking of higher-order and lower-order rhythms involves BM-specific and domaingeneral audiovisual processing, respectively.

To avoid ambiguity, we have removed the sentence “We calculated the audiovisual congruency effect for the upright and the inverted conditions” (line 194, which referred to the calculation of the indices rather than any statistical tests) from the manuscript. We have also clarified the meanings of the findings based on the interaction and simple effects together at the two temporal scales, respectively (Lines 205-207; Lines 213-215).

Author response image 1.

Examples of different patterns of data yielding a significant or nonsignificant interaction effect.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors evaluate spectral changes in electroencephalography (EEG) data as a function of the congruency of audio and visual information associated with biological motion (BM) or non-biological motion. The results show supra-additive power gains in the neural response to gait dynamics, with trials in which audio and visual information was presented simultaneously producing higher average amplitude than the combined average power for auditory and visual conditions alone. Further analyses suggest that such supra-additivity is specific to BM and emerges from temporoparietal areas. The authors also find that the BM-specific supra-additivity is negatively correlated with autism traits.

Strengths:

The manuscript is well-written, with a concise and clear writing style. The visual presentation is largely clear. The study involves multiple experiments with different participant groups. Each experiment involves specific considered changes to the experimental paradigm that both replicate the previous experiment's finding yet extend it in a relevant manner.

Weaknesses:

In the revised version of the paper, the manuscript better relays the results and anticipates analyses, and this version adequately resolves some concerns I had about analysis details. Still, it is my view that the findings of the study are basic neural correlate results that do not provide insights into neural mechanisms or the causal relevance of neural effects towards behavior and cognition. The presence of an inversion effect suggests that the supra-additivity is related to cognition, but that leaves open whether any detected neural pattern is actually consequential for multi-sensory integration (i.e., correlation is not causation). In other words, the fact that frequency-specific neural responses to the [audio & visual] condition are stronger than those to [audio] and [visual] combined does not mean this has implications for behavioral performance. While the correlation to autism traits could suggest some relation to behavior and is interesting in its own right, this correlation is a highly indirect way of assessing behavioral relevance. It would be helpful to test the relevance of supra-additive cortical tracking on a behavioral task directly related to the processing of biological motion to justify the claim that inputs are being integrated in the service of behavior. Under either framework, cortical tracking or entrainment, the causal relevance of neural findings toward cognition is lacking.

Overall, I believe this study finds neural correlates of biological motion, and it is possible that such neural correlates relate to behaviorally relevant neural mechanisms, but based on the current task and associated analyses this has not been shown.

Thank you for providing these thoughtful comments regarding the theoretical implications of our neural findings. Previous behavioral evidence highlights the specificity of the audiovisual integration (AVI) of biological motion (BM) and reveals the impairment of such ability in individuals with autism spectrum disorder. However, the neural implementation underlying the AVI of BM, its specificity, and its association with autistic traits remain largely unknown. The current study aimed to address these issues.

It is noteworthy that the operation of multisensory integration does not always depend on specific tasks, as our brains tend to integrate signals from different sensory modalities even when there is no explicit task. Hence, many studies have investigated multisensory integration at the neural level without examining its correlation with behavioral performance. For example, the widely known super-additivity mode for multisensory integration proposed by Perrault and colleagues was based on single-cell recording findings without behavioral tasks (Perrault et al., 2003, 2005). As we mentioned in the manuscript, the super-additive and sub-additive modes indicate non-linear interaction processing, either with potentiated neural activation to facilitate the perception or detection of near-threshold signals (super-additive) or a deactivation mechanism to minimize the processing of redundant information cross-modally (subadditive) (Laurienti et al., 2005; Metzger et al., 2020; Stanford et al., 2005; Wright et al., 2003). Meanwhile, the additive integration mode represents a linear combination between two modalities. Distinguishing among these integration modes helps elucidate the neural mechanism underlying AVI in specific contexts, even though sometimes, the neural-level AVI effects do not directly correspond to a significant behavioral-level AVI effect (Ahmed et al., 2023; Metzger et al., 2020). In the current study, we unveiled the dissociation of multisensory integration modes between neural responses at two temporal scales (Exps. 1a & 1b), which may involve the cooperation of a domain-specific and a domain-general AVI processes (Exp. 2). While these findings were not expected to be captured by a single behavioral index, they revealed the multifaceted mechanism whereby hierarchical cortical activity supports audiovisual BM integration. They also advance our understanding of the emerging view that multi-timescale neural dynamics coordinate multisensory integration (Senkowski & Engel, 2024), especially from the perspective of natural stimuli processing.

Meanwhile, our finding that the cortical tracking of higher-order rhythmic structure in audiovisual BM specifically correlated with individual autistic traits extends previous behavioral evidence that ASD children exhibited reduced orienting to audiovisual synchrony in BM (Falck-Ytter et al., 2018), offering new evidence that individual differences in audiovisual BM processing are present at the neural level and associated with autistic traits. This finding opens the possibility of utilizing the cortical tracking of BM as a potential neural maker to assist the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder (see more details in our Discussion Lines 334-346).

However, despite the main objective of the current study focusing on the neural processing of BM, we agree with the reviewer that it would be helpful to test the relevance of supra-additive cortical tracking on a behavioral task directly related to BM perception, for further justifying that inputs are being integrated in the service of behavior. In the current study, we adopted a color-change detection task entirely unrelated to audiovisual correspondence but only for maintaining participants’ attention. The advantage of this design is that it allows us to investigate whether and how the human brain integrates audiovisual BM information under task-irrelevant settings, as people in daily life can integrate such information even without a relevant task. However, this advantage is accompanied by a limitation: the task does not facilitate the direct examination of the correlation between neural responses and behavioral performance, since the task performance was generally high (mean accuracy >98% in all experiments). Future research could investigate this issue by introducing behavioral tasks more relevant to BM perception (e.g., Shen et al., 2023). They could also apply advanced neuromodulation techniques to elucidate the causal relevance of the cortical tracking effect to behavior (e.g., Ko sem et al., 2018, 2020).

We have discussed the abovementioned points as a separate paragraph in the revised manuscript (Lines 322-333). In addition, since the scope of the current study does not involve a causal correlation with behavioral performance, we have removed or modified the descriptions related to "functional relevance" in the manuscript (Abstract; Introduction, lines 101-103; Results, lines 239; Discussion, line 336; Supplementary Information, line 794、803). Moreover, we have strengthened the descriptions of the theoretical implications of the current findings in the abstract.

We hope these changes adequately address your concern.

References

Ahmed, F., Nidiffer, A. R., O’Sullivan, A. E., Zuk, N. J., & Lalor, E. C. (2023). The integration of continuous audio and visual speech in a cocktail-party environment depends on attention. Neuroimage, 274, 120143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2023.120143

Falck-Ytter, T., Nystro m, P., Gredeba ck, G., Gliga, T., Bo lte, S., & the EASE team. (2018). Reduced orienting to audiovisual synchrony in infancy predicts autism diagnosis at 3 years of age. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(8), 872–880. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12863

Ko sem, A., Bosker, H., Jensen, O., Hagoort, P., & Riecke, L. (2020). Biasing the Perception of Spoken Words with Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 32, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_01579

Ko sem, A., Bosker, H. R., Takashima, A., Meyer, A., Jensen, O., & Hagoort, P. (2018). Neural Entrainment Determines the Words We Hear. Current Biology, 28(18), 2867-2875.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.07.023

Laurienti, P. J., Perrault, T. J., Stanford, T. R., Wallace, M. T., & Stein, B. E. (2005). On the use of superadditivity as a metric for characterizing multisensory integration in functional neuroimaging studies. Experimental Brain Research, 166(3), 289–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-005-2370-2

Metzger, B. A., Magnotti, J. F., Wang, Z., Nesbitt, E., Karas, P. J., Yoshor, D., & Beauchamp, M. S. (2020). Responses to Visual Speech in Human Posterior Superior Temporal Gyrus Examined with iEEG Deconvolution. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 40(36), 6938–6948. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0279-20.2020

Perrault, T. J., Vaughan, J. W., Stein, B. E., & Wallace, M. T. (2003). Neuron-Specific Response Characteristics Predict the Magnitude of Multisensory Integration. Journal of Neurophysiology, 90(6), 4022–4026. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00494.2003

Perrault, T. J., Vaughan, J. W., Stein, B. E., & Wallace, M. T. (2005). Superior Colliculus Neurons Use Distinct Operational Modes in the Integration of Multisensory Stimuli. Journal of Neurophysiology, 93(5), 2575–2586. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00926.2004

Senkowski, D., & Engel, A. K. (2024). Multi-timescale neural dynamics for multisensory integration. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 25(9), 625–642. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-024-00845-7

Shen, L., Lu, X., Wang, Y., & Jiang, Y. (2023). Audiovisual correspondence facilitates the visual search for biological motion. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 30(6), 2272–2281. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-023-02308-z

Stanford, T. R., Quessy, S., & Stein, B. E. (2005). Evaluating the Operations Underlying Multisensory Integration in the Cat Superior Colliculus. Journal of Neuroscience, 25(28), 6499–6508. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5095-04.2005

Wright, T. M., Pelphrey, K. A., Allison, T., McKeown, M. J., & McCarthy, G. (2003). Polysensory Interactions along Lateral Temporal Regions Evoked by Audiovisual Speech. Cerebral Cortex, 13(10), 1034–1043. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/13.10.1034

-

-

eLife Assessment

Wang et al. presented visual (dot) motion and/or the sound of a walking person and found solid evidence that EEG activity tracks the step rhythm, as well as the gait (2-step cycle) rhythm, with some demonstration that the gait rhythm is tracked superadditively (power for A+V condition is higher than the sum of the A-only and V-only condition). The valuable findings will be of wide interest to those examining biological motion perception and oscillatory processes more broadly. Some of the theoretical interpretations concerning entrainment must remain speculative when the authors cannot dissociate evoked responses from entrained oscillatory effects

-

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

Shen et al. conducted three experiments to study the cortical tracking of the natural rhythms involved in biological motion (BM), and whether these involve audiovisual integration (AVI). They presented participants with visual (dot) motion and/or the sound of a walking person. They found that EEG activity tracks the step rhythm, as well as the gait (2-step cycle) rhythm. The gait rhythm specifically is tracked superadditively (power for A+V condition is higher than the sum of the A-only and V-only condition, Experiments 1a/b), which is independent of the specific step frequency (Experiment 1b). Furthermore, audiovisual integration during tracking of gait was specific to BM, as it was absent (that is, the audiovisual congruency effect) when the walking dot motion was vertically inverted (Experiment …

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

Shen et al. conducted three experiments to study the cortical tracking of the natural rhythms involved in biological motion (BM), and whether these involve audiovisual integration (AVI). They presented participants with visual (dot) motion and/or the sound of a walking person. They found that EEG activity tracks the step rhythm, as well as the gait (2-step cycle) rhythm. The gait rhythm specifically is tracked superadditively (power for A+V condition is higher than the sum of the A-only and V-only condition, Experiments 1a/b), which is independent of the specific step frequency (Experiment 1b). Furthermore, audiovisual integration during tracking of gait was specific to BM, as it was absent (that is, the audiovisual congruency effect) when the walking dot motion was vertically inverted (Experiment 2). Finally, the study shows that an individual's autistic traits are negatively correlated with the BM-AVI congruency effect.

Strengths:

The three experiments are well designed and the various conditions are well controlled. The rationale of the study is clear, and the manuscript is pleasant to read. The analysis choices are easy to follow, and mostly appropriate.

Weaknesses:

There is a concern of double-dipping in one of the tests (Experiment 2, Figure 3: interaction of Upright/Inverted X Congruent/Incongruent). I raised this concern on the original submission, and it has not been resolved properly. The follow-up statistical test (after channel selection using the interaction contrast permutation test) still is geared towards that same contrast, even though the latter is now being tested differently. (Perhaps not explicitly testing the interaction, but in essence still testing the same.) A very simple solution would be to remove the post-hoc statistical tests and simply acknowledge that you're comparing simple means, while the statistical assessment was already taken care of using the permutation test. (In other words: the data appear compelling because of the cluster test, but NOT because of the subsequent t-tests.)

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors evaluate spectral changes in electroencephalography (EEG) data as a function of the congruency of audio and visual information associated with biological motion (BM) or non-biological motion. The results show supra-additive power gains in the neural response to gait dynamics, with trials in which audio and visual information was presented simultaneously producing higher average amplitude than the combined average power for auditory and visual conditions alone. Further analyses suggest that such supra-additivity is specific to BM and emerges from temporoparietal areas. The authors also find that the BM-specific supra-additivity is negatively correlated with autism traits.

Strengths:

The manuscript is well-written, with a concise and clear writing style. The visual presentation is largely …

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors evaluate spectral changes in electroencephalography (EEG) data as a function of the congruency of audio and visual information associated with biological motion (BM) or non-biological motion. The results show supra-additive power gains in the neural response to gait dynamics, with trials in which audio and visual information was presented simultaneously producing higher average amplitude than the combined average power for auditory and visual conditions alone. Further analyses suggest that such supra-additivity is specific to BM and emerges from temporoparietal areas. The authors also find that the BM-specific supra-additivity is negatively correlated with autism traits.

Strengths:

The manuscript is well-written, with a concise and clear writing style. The visual presentation is largely clear. The study involves multiple experiments with different participant groups. Each experiment involves specific considered changes to the experimental paradigm that both replicate the previous experiment's finding yet extend it in a relevant manner.

Weaknesses:

In the revised version of the paper, the manuscript better relays the results and anticipates analyses, and this version adequately resolves some concerns I had about analysis details. Still, it is my view that the findings of the study are basic neural correlate results that do not provide insights into neural mechanisms or the causal relevance of neural effects towards behavior and cognition. The presence of an inversion effect suggests that the supra-additivity is related to cognition, but that leaves open whether any detected neural pattern is actually consequential for multi-sensory integration (i.e., correlation is not causation). In other words, the fact that frequency-specific neural responses to the [audio & visual] condition are stronger than those to [audio] and [visual] combined does not mean this has implications for behavioral performance. While the correlation to autism traits could suggest some relation to behavior and is interesting in its own right, this correlation is a highly indirect way of assessing behavioral relevance. It would be helpful to test the relevance of supra-additive cortical tracking on a behavioral task directly related to the processing of biological motion to justify the claim that inputs are being integrated in the service of behavior. Under either framework, cortical tracking or entrainment, the causal relevance of neural findings toward cognition is lacking.

Overall, I believe this study finds neural correlates of biological motion, and it is possible that such neural correlates relate to behaviorally relevant neural mechanisms, but based on the current task and associated analyses this has not been shown.

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Strengths:

The three experiments are well designed and the various conditions are well controlled. The rationale of the study is clear, and the manuscript is pleasant to read. The analysis choices are easy to follow, and mostly appropriate.

We are grateful to the reviewer’s thoughtful comments.

Weaknesses:

I only have one potential worry. The analysis for gait tracking (1 Hz) in Experiment 2 (Figures 3a/b) starts by computing a congruency effect (A/V stimulation congruent (same frequency) versus A/V incongruent (V at 1 Hz, A at either 0.6 or 1.4 Hz), separately for the Upright and Inverted conditions. Then, this congruency effect is contrasted between Upright and Inverted, in essence computing an interaction score …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Strengths:

The three experiments are well designed and the various conditions are well controlled. The rationale of the study is clear, and the manuscript is pleasant to read. The analysis choices are easy to follow, and mostly appropriate.

We are grateful to the reviewer’s thoughtful comments.

Weaknesses:

I only have one potential worry. The analysis for gait tracking (1 Hz) in Experiment 2 (Figures 3a/b) starts by computing a congruency effect (A/V stimulation congruent (same frequency) versus A/V incongruent (V at 1 Hz, A at either 0.6 or 1.4 Hz), separately for the Upright and Inverted conditions. Then, this congruency effect is contrasted between Upright and Inverted, in essence computing an interaction score (Congruent/Incongruent X Upright/Inverted). Then, the channels in which this interaction score is significant (by cluster-based permutation test; Figure 3a) are subselected for further analysis. This further analysis is shown in Figure 3b and described in lines 195-202. Critically, the further analysis exactly mirrors the selection criteria, i.e. it is aimed at testing the effect of Congruent/Incongruent and Upright/Inverted. This is colloquially known as "double dipping", the same contrast is used for selection (of channels, in this case) as for later statistical testing. This should be avoided, since in this case even random noise might result in a significant effect. To strengthen the evidence, either the authors could use a selection contrast that is orthogonal to the subsequent statistical test, or they could skip either the preselection step or the subsequent test. (It could be argued that the test in Figure 3b and related text is not needed to make the point - that same point is already made by the cluster-based permutation test.)

Thanks for the helpful suggestions. In Experiment 2, to investigate whether the multisensory integration effect was specialized for biological motion perception, we contrasted the congruency effect between the upright and inverted conditions to search for clusters showing a significant interaction effect. We performed further analyses based on neural responses from this cluster to examine whether the congruency effect was significant in the upright and the inverted conditions, respectively, following the logic of post hoc comparisons after identifying an interaction effect. However, we agree with the reviewer that comparing the congruency effects between the upright and inverted conditions again based on data from this cluster was redundant and resulted in doubledipping. Therefore, we have removed this comparison from the main text and optimized the way to present our results in the revised Fig. 3).

Related to the above: the test for the three-way interaction (lines 211-216) is reported as "marginally significant", with a p-value of 0.087. This is not very strong evidence.

As shown in Fig.3b & e, the magnitude of amplitude differs between the gaitcycle frequency (mean = 0.008, SD = 0.038) and the step-cycle frequency (mean = 0.052; SD =0.056), which might influence the statistical results of the interaction effect. To reduce such influence, we converted the amplitude data at each frequency condition into Z-scores, separately. The repeated-measures ANOVA analysis on these normalized amplitude data revealed a significant three-way interaction (F (1,23) = 7.501, p = 0.012, ƞp2 = 0.246). We have updated the results in the revised manuscript (lines 218-225).

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations For The Authors):

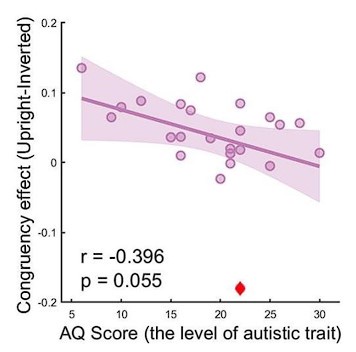

- Which variable caused one data point to be classified as outlier? (line 221).

The outlier is a participant whose audiovisual congruency effect (Upright – Inverted) in neural responses at the frequency of interest exceeds 3 SD from the group mean. It is marked by a red diamond in Author response 2. Before removing the data, the correlation between the AQ score and the congruency effect is r = -0.396, p = 0.055. For comparison, the results after removing the outlier are shown in Fig. 3c of the revised manuscript. We have added more information about the variable causing the outlier in the revised manuscript (lines 231-232).

Author response image 1.

The correlation between AQ score and congruency effect

- The authors cite Maris & Oostenveld (2007) in line 415 as the main reference for the FieldTrip toolbox, but the correct reference here is different, see https://www.fieldtriptoolbox.org/faq/how_should_i_refer_to_fieldtrip_in_my_p ublication/

Thank you for pointing out this issue. Citation corrected.

- The authors could consider giving some more background on the additive vs superadditive distinction in the Introduction, which may increase the impact; as it stands the reader might not know why this is particularly interesting. Summarize some of the takeaways of the Stevenson et al. (2014) review in this respect.

Thanks for the suggestion and we have added the following relevant information in the Introduction (lines 80-90):

“Moreover, we adopted an additive model to classify multisensory integration based on the AV vs A+V comparison. This model assumes independence between inputs from each sensory modality and distinguishes among sub-additive (AV < A+V), additive (AV = A+V), and super-additive (AV > A+V) response modes (see a review by Stevenson et al., 2014). The additive mode represents a linear combination between two modalities. In contrast, the super-additive and subadditive modes indicate non-linear interaction processing, either with potentiated neural activation to facilitate the perception or detection of nearthreshold signals (super-additive) or a deactivation mechanism to minimize the processing of redundant information cross-modally (sub-additive) (Laurienti et al., 2005; Metzger et al., 2020; Stanford et al., 2005; Wright et al., 2003).”

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Strengths:

The manuscript is well-written, with a concise and clear writing style. The visual presentation is largely clear. The study involves multiple experiments with different participant groups. Each experiment involves specific considered changes to the experimental paradigm that both replicate the previous experiment's finding yet extend it in a relevant manner.

We thank the reviewer for the valuable feedback.

Weaknesses:

The manuscript interprets the neural findings using mechanistic and cognitive claims that are not justified by the presented analyses and results.

First, entrainment and cortical tracking are both invoked in this manuscript, sometimes interchangeably so, but it is becoming the standard of the field to recognize their separate evidential requirements. Namely, step and gate cycles are striking perceptual or cognitive events that are expected to produce event-related potentials (ERPs). The regular presentation of these events in the paradigm will naturally evoke a series of ERPs that leave a trace in the power spectrum at stimulation rates even if no oscillations are at play. Thus, the findings should not be interpreted from an entrainment framework except if it is contextualized as speculation, or if additional analyses or experiments are carried out to support the assumption that oscillations are present. Even if oscillations are shown to be present, it is then a further question whether the oscillations are causally relevant toward the integration of biological motion and for the orchestration of cognitive processes.

Second, if only a cortical tracking account is adopted, it is not clear why the demonstration of supra-additivity in spectral amplitude is cognitively or behaviorally relevant. Namely, the fact that frequency-specific neural responses to the [audio & visual] condition are stronger than those to [audio] and [visual] combined does not mean this has implications for behavioral performance. While the correlation to autism traits could suggest some relation to behavior and is interesting in its own right, this correlation is a highly indirect way of assessing behavioral relevance. It would be helpful to test the relevance of supra-additive cortical tracking on a behavioral task directly related to the processing of biological motion to justify the claim that inputs are being integrated with the service of behavior. Under either framework, cortical tracking or entrainment, the causal relevance of neural findings toward cognition is lacking.

Overall, I believe this study finds neural correlates of biological motion, and it is possible that such neural correlates relate to behaviorally relevant neural mechanisms, but based on the current task and associated analyses this has not been shown.

Thanks for raising the important concerns regarding the interpretation of our results within the entrainment or the cortical tracking frame. A strict neural entrainment account emphasizes the alignment of endogenous neural oscillations with external rhythms, rather than a mere regular repetition of stimulus-evoked responses. However, it is challenging to fully dissociate these components, given that rhythmic stimulation can shape intrinsic neural oscillations, resulting in an intricate interplay between endogenous neural oscillations and stimulus-evoked responses (Duecker et al., 2024; Herrmann et al., 2016; Hosseinian et al., 2021). Therefore, some research, including the current study, use the term “entrainment” to refer to the alignment of brain activity to rhythmic stimulation in a broader context, without isolating the intrinsic oscillations and evoked responses (e.g., Ding et al., 2016; Nozaradan et al., 2012; Obleser & Kayser, 2019). Nevertheless, we agree with the reviewer that since the current results did not examine or provide direct evidence for endogenous oscillations, it is better to contextualize the oscillation view as speculations. Hence, we have replaced most of the expressions about “entrainment” with a more general term “tracking” in the revised manuscript (as well as in the title of the manuscript). We only briefly mentioned the entrainment account in the Discussion to facilitate comparison with the literature (lines 307-312).

Regarding the relevance between neural findings and cognition or behavioral performance, the first supporting evidence comes from the inversion effect in Experiment 2. For the neural responses at gait-cycle frequency, we observed a significantly enhanced audiovisual congruency effect in the upright condition compared with the inverted condition. Inversion disrupts the distinctive kinematic features of biological motion (e.g., gravity-compatible ballistic movements) and significantly impairs biological motion processing, but it does not change the basic visual properties of the stimuli, including the rhythmic signals generated by low-level motion cues. Therefore, the inversion effect has long been regarded as an indicator of the specificity of biological motion processing in numerous behavioral and neuroimaging studies (Bardi et al., 2014; Grossman & Blake, 2001; Shen, Lu, Yuan, et al., 2023; Simion et al., 2008; Troje & Westhoff, 2006; Vallortigara & Regolin, 2006; Wang et al., 2014; Wang & Jiang, 2012; Wang et al., 2022). Here, our finding of the cortical tracking of higher-order rhythmic structures (gait cycles) present in the upright but not in the inverted condition suggests that this cortical tracking effect can not be explained by ERPs evoked by regular onsets of rhythmic events. Rather, it is closely linked with the specialized cognitive processing of biological motion. Furthermore, we found that the BM-specific cortical tracking effect at gait-cycle frequency (rather than the non-selective tracking effect at step-cycle frequency) correlates with observers’ autistic traits, indicating its functional relevance to social cognition. These findings convergingly suggest that the cortical tracking effect that we currently observed engages cognitively relevant neural mechanisms. In addition, our recent behavioral study showed that listening to frequency-congruent footstep sounds, compared with incongruent sounds, enhanced the visual search for human walkers but not for non-biological motion stimuli containing the same rhythmic signals (Shen, Lu, Wang, et al., 2023). These results suggest that audiovisual correspondence specifically enhances the perceptual and attentional processing of biological motion. Future research could examine whether the cortical tracking of rhythmic structures plays a functional role in this process, which may shed more light on the behavioral relevance of the cortical tracking effect to biological motion perception. We have incorporated the above information into the Discussion (lines 268-293).

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations For The Authors):

In Figure 1c, it could be helpful to add the word "static" in the illustration for the auditory condition so that readers understand without reading the subtext that it is a static image without biological motion.

Suggestion taken.

In the Discussion, I believe it is important to justify an oscillation and entrainment account, or if it cannot be justified based on the current results and analyses (which is my opinion), it could be helpful to explicitly frame it as speculation.

We agree with the reviewer. For more clarification, please refer to our response to the public review.

L335, I did not understand this sentence - a reformulation would be helpful.

The point-light stimuli were created by capturing the motion of a walking actor (Vanrie & Verfaillie, 2004). The global motion of the walking sequences was eliminated so that the point-light walker looks like walking on a treadmill without translational motion. We have reformulated the sentence as follows: “The point-light walker was presented at the center of the screen without translational motion.”

The results in Figure 2a and 2d are derived by performing a t-test between the amplitude at the frequency of gait and step cycles and zero. Comparison against amplitude of zero is too liberal; the possibility for a Type-I error is inflated because even EEG data with only noise will not have amplitudes of zero at all frequencies. A better baseline (H0) is either the 1/frequency trend in the power spectrum derived using methods like FOOOF (https://fooof-tools.github.io/fooof/) or by performing non-parametric shuffling based methods (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.03.024).

In our data analysis, instead of performing the t-test between raw amplitude with zero, we compared the normalized amplitude at each frequency bin (by subtracting the average amplitude measured at the neighboring frequency bins from the original amplitude data) against zero. Such analysis is equal to contrasting the raw amplitude to its neighboring frequency bins, allowing us to test whether the neural response in each frequency bin showed a significant enhancement compared with its neighbors. The multiple comparisons on each frequency bin were controlled by false discovery rate (FDR) correction, reducing the Type-I error. Such analysis procedures help reduce (though not totally remove) the influence of the 1/f trend and have been widely used in this field (Cirelli et al., 2016; Henry & Obleser, 2012; Lenc et al., 2018; Nozaradan et al., 2012; Peter et al., 2023).

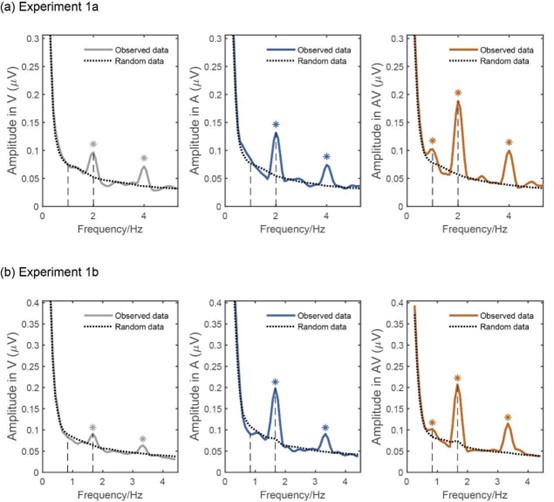

To further verify our findings, we adopted the reviewer’s suggestion and created a baseline by performing a non-parametric shuffling-based analysis. More specifically, to establish the statistical significance of amplitude peaks, we carried out a surrogate analysis on each condition. For each participant, a single control surrogate dataset was derived from their actual dataset by jittering the onset of each step-cycle relative to the actual original onset by a randomly selected integer value ranging between − 490–490 ms. This procedure removed the consistent relationship between the EEG signal and the stimuli while preserving each epoch’s general timing within the exposure period. Then, epochs were extracted based on surrogate stimuli onset, and amplitude was computed across frequencies through FFT under a null model of non-entrainment (Moreau et al., 2022). This entire procedure was performed 100 times, producing a surrogate amplitude distribution of 100 group-averaged values for each condition. If the observed amplitude values at the frequency of interest exceeded the value corresponding to the 95th percentile of the surrogate distribution (p < .05) within a given condition (e.g., AV), the amplitude peak was considered significant (Batterink, 2020). As shown in Author response image 2, the statistical results from these analyses are similar to those reported in the manuscript, confirming the significant amplitude peaks at the frequencies of interest.

Author response image 2.

Non-parametric analysis for spectral peak. The dotted lines represent the random data based on shuffling analysis. The solid lines represent the observed data in measured EEG signals. All conditions induced significant peaks at step-cycle frequency and its harmonic, while only the AV condition induced a significant peak at gait-cycle frequency.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Strengths:

The main strengths of the paper relate to the conceptualization of BM and the way it is operationalized in the experimental design and analyses. The use of entrainment, and the tracking of different, nested aspects of BM result in seemingly clean data that demonstrate the basic pattern. The first experiments essentially provide the basic utility of the methodological innovation and the second experiment further hones in on the relevant interpretation of the findings by the inclusion of better control stimuli sets.

Another strength of the work is that it includes at a conceptual level two replications.

We appreciate the reviewer for the comprehensive review and positive comments.

Weaknesses:

The statistical analysis is misleading and inadequate at times. The inclusion of the autism trait is not foreshadowed and adequately motivated and is likely underpowered. Finally, a broader discussion over other nested frequencies that might reside in the point-light walker stimuli would also be important to fully interpret the different peaks in the spectra.

(1) Regarding the nested frequency peaks in the spectra, we did observe multiple significant amplitude peaks at 1f (1/0.83 Hz), 2f (2/1.67 Hz), and 4f (4/3.33 Hz) relative to the gait-cycle frequency (Fig. 2 a&d). To further test the functional roles of the neural activity at different frequencies, we analyzed the audiovisual integration modes at each frequency. Note that we collapsed the data from Experiments 1a & 1b in the analysis as they yielded similar results. Overall, results show a similar additive audiovisual integration mode at 2f and 4f and a super-additive integration mode only at 1f (Figure S1), suggesting that the cortical tracking effects at 2f and 4f may be functionally linked but independent of that at 1f. We have reported the detailed results in the Supplementary Information.

(2) For the reviewer’s other concerns about statistical analysis and autism traits, please refer to our responses below to the Recommendations for the authors.

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations For The Authors):

The description of the analyses performed for experiment 2 comes across as double dipping. Congruency effects for BM and non-BM motion (inverted) were compared using cluster-based statistics. Then identified clusters informed an averaging of signals which then were subjected to a paired comparison. At this point, it is no surprise that these paired comparisons are highly significant seeing that the channels were selected based on a cluster analysis of the same exact contrast. This approach should be avoided.

In the analysis of the repeated measures ANOVA reporting a trend as marginally significant is misleading. Reporting the statistical results whilst indicating that those do not reach significance is the appropriate way to communicate this finding. Other statistics can be used in order to provide the likelihood of those findings supporting H1 or H0 if the authors would like to state something more precise (Bayesian).

Thanks for the comments. We have addressed these two points in our response to the public review of Reviewer #1.

The authors perform a correlation along "autistic trait" scores in an individual differences approach. Individual differences are typically investigated in larger samples (>n=40). In addition, the range of AQ scores seems limited to mostly average or lower-than-average AQs (barring a couple). These points make the conclusions on the possible role of BM in the autistic phenotype very tentative. I would recommend acknowledging this.

An alternative analysis approach that might better suit the smaller sample size is a comparison between high and low AQ participants, defined based on a median split.

Many thanks for the suggestion. We agree with the reviewer that the sample size (n = 24) in the current study is not large for exploring the correlation between BM and autistic traits. The narrow range of AQ scores was due to the fact that all participants were non-clinical populations and we did not pre-select participants by AQ scores. To further confirm our findings, we adopted your suggestion to compare the BM-specific cortical tracking effect (i.e., audiovisual congruency effect (Upright - Inverted)) between high and low AQ participants split by the median AQ score (20) of this sample. Similar to correlation analysis, one outlier, whose audiovisual congruency effect (Upright – Inverted) in neural responses at 1 Hz exceeds 3 SD from the group mean, was removed from the following analysis. As shown in Figure S3, at 1 Hz, participants with low AQ showed a greater cortical tracking effect compared with high AQ participants (t (21) = 2.127, p = 0.045). At 2 Hz, low and high AQ participants showed comparable neural responses (t (22) = 0.946, p = 0.354). These results are in line with the correlation analysis, providing further support to the functional relevance between social cognition and cortical tracking of biological motion as well as its dissociation at the two temporal scales. We have added these results to the main text (lines 238-244) and the supplementary information.

Writing

The narrative could be better unfolded and studies better motivated. The transition from basic science research on BM to possibly delineating a mechanistic understanding of autism was a surprise at the end of the intro. Once the authors consider the suggestions and comments above it would be good to have this detail and motivation more obviously foreshadowed in the text.

Thanks for the great suggestion and we have provided an introduction about how audiovisual BM processing links with social cognition and ASD in the first paragraph of the revised manuscript (lines 46-56). In particular, integrating multisensory BM cues is foundational for perceiving and attending to other people and developing further social interaction. However, such ability is usually compromised in people with social deficits, such as individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (Feldman et al., 2018), and even in non-clinical populations with high autistic traits (Ujiie et al., 2015). These behavioral findings underline the close relationship between multisensory BM processing and one’s social cognitive capability, motivating us to further explore this issue at the neural level in the current study. We have also modified the relevant content in the last paragraph of the Introduction (lines 100-108), briefly mentioning the methods that we used to investigate this issue.

The use of terminology related to neural oscillations which are entraining to the BM seems to suggest that the rhythmic tracking inevitably stems from the shaping of existing intrinsic dynamics of the brain. I am not sure this is necessarily the case. I would therefore adopt a more concrete jargon for the description of the entrainment seen in this study. If a discussion over internal dynamics shaped by external stimuli should be invoked, it should be done explicitly with appropriate references (but in my opinion, it isn't quite required).

Please refer to our response to a similar point raised in the public review of Reviewer #2.

References

Bardi, L., Regolin, L., & Simion, F. (2014). The First Time Ever I Saw Your Feet: Inversion Effect in Newborns’ Sensitivity to Biological Motion. Developmental Psychology, 50. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034678

Baron-Cohen, S., Wheelwright, S., Skinner, R., Martin, J., & Clubley, E. (2001). The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): Evidence from Asperger syndrome/highfunctioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 31(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1005653411471

Batterink, L. (2020). Syllables in Sync Form a Link: Neural Phase-locking Reflects Word Knowledge during Language Learning. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 32(9), 1735–1748. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_01581

Cirelli, L. K., Spinelli, C., Nozaradan, S., & Trainor, L. J. (2016). Measuring Neural Entrainment to Beat and Meter in Infants: Effects of Music Background. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2016.00229

Ding, N., Melloni, L., Zhang, H., Tian, X., & Poeppel, D. (2016). Cortical tracking of hierarchical linguistic structures in connected speech. Nature Neuroscience, 19(1), 158–164. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4186

Duecker, K., Doelling, K. B., Breska, A., Coffey, E. B. J., Sivarao, D. V., & Zoefel, B. (2024). Challenges and approaches in the study of neural entrainment. Journal of Neuroscience, 44(40). https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1234-24.2024

Falck-Ytter, T., Nyström, P., Gredebäck, G., Gliga, T., Bölte, S., & the EASE team. (2018). Reduced orienting to audiovisual synchrony in infancy predicts autism diagnosis at 3 years of age. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 59(8), 872–880. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12863

Feldman, J. I., Dunham, K., Cassidy, M., Wallace, M. T., Liu, Y., & Woynaroski, T. G. (2018). Audiovisual multisensory integration in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 95, 220–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.09.020

Grossman, E. D., & Blake, R. (2001). Brain activity evoked by inverted and imagined biological motion. Vision Research, 41(10), 1475–1482. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0042-6989(00)00317-5

Henry, M. J., & Obleser, J. (2012). Frequency modulation entrains slow neural oscillations and optimizes human listening behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(49), 20095–20100. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1213390109

Herrmann, C. S., Murray, M. M., Ionta, S., Hutt, A., & Lefebvre, J. (2016). Shaping Intrinsic Neural Oscillations with Periodic Stimulation. Journal of Neuroscience, 36(19), 5328–5337. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0236-16.2016

Hosseinian, T., Yavari, F., Biagi, M. C., Kuo, M.-F., Ruffini, G., Nitsche, M. A., & Jamil, A. (2021). External induction and stabilization of brain oscillations in the human. Brain Stimulation, 14(3), 579–587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2021.03.011

Klin, A., Lin, D. J., Gorrindo, P., Ramsay, G., & Jones, W. (2009). Two-year-olds with autism orient to non-social contingencies rather than biological motion. Nature, 459(7244), 257–261. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07868

Laurienti, P. J., Perrault, T. J., Stanford, T. R., Wallace, M. T., & Stein, B. E. (2005). On the use of superadditivity as a metric for characterizing multisensory integration in functional neuroimaging studies. Experimental Brain Research, 166(3), 289–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-005-2370-2

Lenc, T., Keller, P. E., Varlet, M., & Nozaradan, S. (2018). Neural tracking of the musical beat is enhanced by low-frequency sounds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(32), 8221–8226. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1801421115

Metzger, B. A., Magnotti, J. F., Wang, Z., Nesbitt, E., Karas, P. J., Yoshor, D., & Beauchamp, M. S. (2020). Responses to Visual Speech in Human Posterior Superior Temporal Gyrus Examined with iEEG Deconvolution. The Journal of Neuroscience: The Official Journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 40(36), 6938–6948. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0279-20.2020

Moreau, C. N., Joanisse, M. F., Mulgrew, J., & Batterink, L. J. (2022). No statistical learning advantage in children over adults: Evidence from behaviour and neural entrainment. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 57, 101154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2022.101154

Nozaradan, S., Peretz, I., & Mouraux, A. (2012). Selective Neuronal Entrainment to the Beat and Meter Embedded in a Musical Rhythm. Journal of Neuroscience, 32(49), 17572–17581. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3203-12.2012

Obleser, J., & Kayser, C. (2019). Neural Entrainment and Attentional Selection in the Listening Brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 23(11), 913–926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2019.08.004

Peter, V., Goswami, U., Burnham, D., & Kalashnikova, M. (2023). Impaired neural entrainment to low frequency amplitude modulations in English-speaking children with dyslexia or dyslexia and DLD. Brain and Language, 236, 105217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2022.105217

Shen, L., Lu, X., Wang, Y., & Jiang, Y. (2023). Audiovisual correspondence facilitates the visual search for biological motion. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 30(6), 2272–2281. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-023-02308-z

Shen, L., Lu, X., Yuan, X., Hu, R., Wang, Y., & Jiang, Y. (2023). Cortical encoding of rhythmic kinematic structures in biological motion. NeuroImage, 268, 119893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2023.119893

Simion, F., Regolin, L., & Bulf, H. (2008). A predisposition for biological motion in the newborn baby. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(2), 809–813. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0707021105

Stanford, T. R., Quessy, S., & Stein, B. E. (2005). Evaluating the Operations Underlying Multisensory Integration in the Cat Superior Colliculus. Journal of Neuroscience, 25(28), 6499–6508. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5095-04.2005

Stevenson, R. A., Ghose, D., Fister, J. K., Sarko, D. K., Altieri, N. A., Nidiffer, A. R., Kurela, L. R., Siemann, J. K., James, T. W., & Wallace, M. T. (2014). Identifying and Quantifying Multisensory Integration: A Tutorial Review. Brain Topography, 27(6), 707–730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10548-014-0365-7

Troje, N. F., & Westhoff, C. (2006). The Inversion Effect in Biological Motion Perception: Evidence for a “Life Detector”? Current Biology, 16(8), 821–824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.022

Ujiie, Y., Asai, T., & Wakabayashi, A. (2015). The relationship between level of autistic traits and local bias in the context of the McGurk effect. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00891

Vallortigara, G., & Regolin, L. (2006). Gravity bias in the interpretation of biological motion by inexperienced chicks. Current Biology, 16(8), R279–R280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2006.03.052

Vanrie, J., & Verfaillie, K. (2004). Perception of biological motion: A stimulus set of human point-light actions. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 625–629. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206542

Wang, L., & Jiang, Y. (2012). Life motion signals lengthen perceived temporal duration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(11), E673-677. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1115515109

Wang, L., Yang, X., Shi, J., & Jiang, Y. (2014). The feet have it: Local biological motion cues trigger reflexive attentional orienting in the brain. NeuroImage, 84, 217–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.041

Wang, Y., Zhang, X., Wang, C., Huang, W., Xu, Q., Liu, D., Zhou, W., Chen, S., & Jiang, Y. (2022). Modulation of biological motion perception in humans by gravity. Nature Communications, 13(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-30347-y

Wright, T. M., Pelphrey, K. A., Allison, T., McKeown, M. J., & McCarthy, G. (2003). Polysensory Interactions along Lateral Temporal Regions Evoked by Audiovisual Speech. Cerebral Cortex, 13(10), 1034–1043. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/13.10.1034