Optogenetic control of a GEF of RhoA uncovers a signaling switch from retraction to protrusion

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

eLife Assessment

This important study combines compelling experiments with optogenetic actuation and convincing theory to understand how signalling proteins control the switch between cell protrusion and retraction, two essential processes in single cell migration. The authors examine the importance of the basal concentration and recruitment dynamics of a guanine exchange factor (GEF) on the activity of the downstream effectors RhoA and Cdc42, which control retraction and protrusion. The experimental and theoretical evidence provides a model of RhoA's involvement in both protrusion and retraction and shows that these complex processes are highly dependent on the concentration and activity dynamics of the components.

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

The ability of a single protein to trigger different functions is an assumed key feature of cell signaling, yet there are very few examples demonstrating it. Here, using an optogenetic tool to control membrane localization of RhoA nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs), we present a case where the same protein can trigger both protrusion and retraction when recruited to the plasma membrane, polarizing the cell in two opposite directions. We show that the basal concentration of the GEF prior to activation predicts the resulting phenotype. A low concentration leads to retraction, whereas a high concentration triggers protrusion. This unexpected protruding behavior arises from the simultaneous activation of Cdc42 by the GEF and sequestration of active RhoA by the GEF PH domain at high concentrations. We propose a minimal model that recapitulates the phenotypic switch, and we use its predictions to control the two phenotypes within selected cells by adjusting the frequency of light pulses. Our work exemplifies a unique case of control of antagonist phenotypes by a single protein that switches its function based on its concentration or dynamics of activity. It raises numerous open questions about the link between signaling protein and function, particularly in contexts where proteins are highly overexpressed, as often observed in cancer.

Article activity feed

-

-

-

-

eLife Assessment

This important study combines compelling experiments with optogenetic actuation and convincing theory to understand how signalling proteins control the switch between cell protrusion and retraction, two essential processes in single cell migration. The authors examine the importance of the basal concentration and recruitment dynamics of a guanine exchange factor (GEF) on the activity of the downstream effectors RhoA and Cdc42, which control retraction and protrusion. The experimental and theoretical evidence provides a model of RhoA's involvement in both protrusion and retraction and shows that these complex processes are highly dependent on the concentration and activity dynamics of the components.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

De Seze et al. investigated the role of guanine exchange factors (GEFs) in controlling cell protrusion and retraction. In order to causally link protein activities to the switch between the opposing cell phenotypes, they employed optogenetic versions of GEFs which can be recruited to the plasma membrane upon light exposure and activate their downstream effectors. Particularly the RhoGEF PRG could elicit both protruding and retracting phenotypes. Interestingly, the phenotype depended on the basal expression level of the optoPRG. By assessing the activity of RhoA and Cdc42, the downstream effectors of PRG, the mechanism of this switch was elucidated: at low PRG levels, RhoA is predominantly activated and leads to cell retraction, whereas at high PRG levels, both RhoA and Cdc42 are activated but PRG also …

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

De Seze et al. investigated the role of guanine exchange factors (GEFs) in controlling cell protrusion and retraction. In order to causally link protein activities to the switch between the opposing cell phenotypes, they employed optogenetic versions of GEFs which can be recruited to the plasma membrane upon light exposure and activate their downstream effectors. Particularly the RhoGEF PRG could elicit both protruding and retracting phenotypes. Interestingly, the phenotype depended on the basal expression level of the optoPRG. By assessing the activity of RhoA and Cdc42, the downstream effectors of PRG, the mechanism of this switch was elucidated: at low PRG levels, RhoA is predominantly activated and leads to cell retraction, whereas at high PRG levels, both RhoA and Cdc42 are activated but PRG also sequesters the active RhoA, therefore Cdc42 dominates and triggers cell protrusion. Finally, they create a minimal model that captures the key dynamics of this protein interaction network and the switch in cell behavior.

The conclusions of this study are strongly supported by data, harnessing the power of modelling and optogenetic activation. The minimal model captures well the dynamics of RhoA and Cdc42 activation and predicts that by changing the frequency of optogenetic activation one can switch between protruding and retracting behaviour in the same cell of intermediate optoPRG level. The authors are indeed able to demonstrate this experimentally albeit with a very low number of cells. A major caveat of this study is that global changes due to PRG overexpression cannot be ruled out. Also, a quantification of absolute protein concentration, which is notoriously difficult, would be useful to put the level of overexpression here in perspective with endogenous levels. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether in cases of protein overexpression in vivo such as cancer, PRG or other GEFs can activate alternative migratory behaviours.

Previous work has implicated RhoA in both protrusion and retraction depending on the context. The mechanism uncovered here provides a convincing explanation for this conundrum. In addition to PRG, optogenetic versions of two other GEFs, LARG and GEF-H1, were used which produced either only one phenotype or less response than optoPRG, underscoring the functional diversity of RhoGEFs. The authors chose transient transfection to achieve a large range of concentration levels and, to find transfected cells at low cell density, developed a small software solution (Cell finder), which could be of interest for other researchers.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

This manuscript builds from the interesting observation that local recruitment of the DHPH domain of the RhoGEF PRG can induce local retraction, protrusion, or neither. The authors convincingly show that these differential responses are tied to the level of expression of the PRG transgene. This response depends on the Rho-binding activity of the recruited PH domain and is associated with and requires (co?)-activation of Cdc42. This begs the question of why this switch in response occurs. They use a computational model to predict that the timing of protein recruitment can dictate the output of the response in cells expressing intermediate levels and found that, "While the majority of cells showed mixed phenotypes irrespectively of the activation pattern, in few cells (3 out of 90) we were able to alternate …

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

This manuscript builds from the interesting observation that local recruitment of the DHPH domain of the RhoGEF PRG can induce local retraction, protrusion, or neither. The authors convincingly show that these differential responses are tied to the level of expression of the PRG transgene. This response depends on the Rho-binding activity of the recruited PH domain and is associated with and requires (co?)-activation of Cdc42. This begs the question of why this switch in response occurs. They use a computational model to predict that the timing of protein recruitment can dictate the output of the response in cells expressing intermediate levels and found that, "While the majority of cells showed mixed phenotypes irrespectively of the activation pattern, in few cells (3 out of 90) we were able to alternate the phenotype between retraction and protrusion several times at different places of the cell by changing the frequency while keeping the same total integrated intensity (Figure 6F and Supp Movie)."

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors):

While the authors have responded to most of the comments, a number of issues remain, most of which pertain to imprecise writing, as previously mentioned.

In the second revision of our manuscript, we tried our best to precise our writing.

For example, at high concentrations of PRG-GEF, the authors repeatedly state that RhoA is inhibited (including in the summary). While this may be functionally valid, it is imprecise. RhoA is activated (not inhibited), but its ability to promote contractility is impaired, presumably as a consequence of sequestration of the active GTPase by the PH domain of PRG-GEF. To put a finer point on this, the activity of RhoA•GTP is to bind to proteins that selectively bind active RhoA. …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors):

While the authors have responded to most of the comments, a number of issues remain, most of which pertain to imprecise writing, as previously mentioned.

In the second revision of our manuscript, we tried our best to precise our writing.

For example, at high concentrations of PRG-GEF, the authors repeatedly state that RhoA is inhibited (including in the summary). While this may be functionally valid, it is imprecise. RhoA is activated (not inhibited), but its ability to promote contractility is impaired, presumably as a consequence of sequestration of the active GTPase by the PH domain of PRG-GEF. To put a finer point on this, the activity of RhoA•GTP is to bind to proteins that selectively bind active RhoA. One such protein the PH domain of PRG. In the case where PRG is overexpressed, RhoA•GTP binds to PRG. Due to the high concentrations of PRG in some cells, this outcompetes the ability of RhoA•GTP to bind other effectors such as formins or ROCK. However, there no strong evidence that RhoA is inhibited. The only hint of such evidence is a reduction in the biosensor for active RhoA, but this too is likely outcompeted by the overexpressed active GEF. There does not appear to be any disagreement about the mechanism, but rather a semantic difference.

We thank Reviewer #2 for emphasizing this semantic concern, which indeed requires clarification. We agree that RhoA is not chemically inactivated; rather, the protein remains active but is functionally sequestered. Our use of the term “inhibition” was intended to describe functional inhibition, consistent with the definition of inhibition as the act of reducing, preventing, or blocking a process, activity, or function. However, we recognize that this terminology could be interpreted as imprecise. To address this, we have clarified the text by explicitly referring to "functional inhibition of RhoA signaling" where appropriate, or by rewording to terms such as "competitive inhibition of RhoA effector binding" to more accurately reflect the mechanism.

Overall, the manuscript is written in a conversational style, not with the precision expected of a scientific manuscript.

We acknowledge Reviewer #2’s comment regarding the style of our manuscript. While our manuscript adopts a somewhat conversational tone, this was a deliberate choice. We believe this style helps engage the reader and facilitates understanding of our reasoning, guided by the philosophy that science is conducted by humans and should be communicated in a way that resonates with them. That said, we fully agree that this approach should not compromise scientific precision. In response to this feedback, we have revised the manuscript to ensure greater clarity and precision while maintaining the approachable style we have chosen.

To exemplify this, I provide an alternative phrasing of one such paragraph.

Lines 51-62:

Here, contrarily to previous optogenetic approaches, we report a serendipitous discovery where the optogenetic recruitment at the plasma membrane of GEFs of RhoA triggers both protrusion and retraction in the same cell type, polarizing the cell in opposite directions. In particular, one GEF of RhoA, PDZ-RhoGEF (PRG), also known as ARHGEF11, was most efficient in eliciting both phenotypes. We show that the outcome of the optogenetic perturbation can be predicted by the basal GEF concentration prior to activation. At high concentration, we demonstrate that Cdc42 is activated together with an inhibition of RhoA by the GEF leading to a cell protrusion. Thanks to the prediction of a minimal mathematical model, we can induce both protrusion and retraction in the same cell by modulating the frequency of light pulses. Our ability to control both phenotypes with a single protein on timescales of second provides a clear and causal demonstration of the multiplexing capacity of signaling circuits.

Here, we report that the phenotypic consequences of plasma membrane recruitment of a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF), PDZ-RhoGEF (PRG, aka ARHGEF11) depends on the level of expression and degree of recruitment of the GEF. At low concentrations, recruitment of PRG induces cell retraction, consistent with the expected function of a GEF for RhoA. However, at high concentrations, Cdc42 is activated, leading to cell protrusion. A minimal mathematical predicts, and experimental observations confirm, that the extent of recruitment determines the consequences of GEF recruitment. The ability of a single GEF to induce disparate outcomes demonstrates the multiplexing capacity of signaling circuits.

We thank Reviewer #2 for providing an alternative phrasing for lines 51–62. We appreciate the effort to enhance clarity and precision in this key section of the manuscript. While we agree with many aspects of the suggested revision and have incorporated several elements to improve the text, we have also retained aspects of our original phrasing that align with the overall tone and structure of the manuscript. Specifically, we have ensured that the balance between precision and accessibility is maintained while integrating the reviewer's suggestions. We hope that the revised text now addresses the concerns raised.

Key points to correct throughout the manuscript are:

- overexpression of PRG does not "inhibit" RhoA.

- retraction and protrusion are distinct phenotypes, they are not opposite phenotypes. One results from RhoA activation, the other results from Cdc42 activation.

Regarding the term “inhibition,” we agree with the reviewer’s point and have addressed this in our earlier comment.

Regarding the terminology of "opposite phenotypes," we believe this description is valid. While protrusion and retraction arise from distinct signaling pathways (Cdc42 activation and RhoA activation, respectively), we describe them as opposite phenotypes because they represent mutually exclusive cellular behaviors. A cell cannot protrude and retract at the same location simultaneously; instead, these behaviors represent opposing ends of the dynamic spectrum of cell morphology.

Here are some other places where editing would improve the manuscript (a noncomprehensive list).

We went through the whole manuscript to improve the scientific precision according to Reviewer #2 comment on the terminology “inhibition”.

line 15 "inhibition of RhoA by the PH domain of the GEF at high concentrations."

We modified the wording: “sequestration of active RhoA by the GEF PH domain at high concentrations”

line 51 "Here, contrarily to previous optogenetic approaches"

We removed “contrarily to previous optogenetic approaches"

line 141 "We next wonder what could differ in the activated cells that lead to the two opposite phenotypes." (the state of mind of the authors is not relevant)

As explained earlier, we made the choice to keep our writing style.

line 185 "Very surprised by this ability of one protein to trigger opposite phenotypes"

As explained earlier, we made the choice to keep our writing style.

lines 206 ff "As our optogenetic tool prevented us from using FRET biosensors because of spectral overlap, we turned to a relocation biosensor that binds RhoA in its GTP form. This highly sensitive biosensor is based on the multimeric TdTomato, whose spectrum overlaps with the RFPt fluorescent protein used for quantifying optoPRG recruitment. We thus designed a new optoPRG with iRFP, which could trigger both phenotypes *but was harder to transiently express* (?? what does this have to do with the spectral overlap), giving rise to a majority of retracting phenotype. *Looking at the RhoA biosensor*, we saw very different responses for both phenotypes (Figure 3G-I). "

We have clarified.

lines 231ff "RhoA activity shows a very different behavior: it first decays, and then rises. It seems that, adding to the well-known activation of RhoA, PRG DH-PH can also negatively regulate RhoA activity." again, RhoA activity may appear to decay, but this is a limitation of the measurements. RhoA is likely activated to the GTP-bound form. PRG is not negatively regulating RhoA activity. An activity that prevents nucleotide exchange by RhoA or accelerates its hydrolysis would constitute negative regulation of RhoA.

We modified the wording to clarify the sentence.

The attempts to quantify the degree of overexpression, though rough, should be included in the version of record. It is not clear how that estimate was generated.

The estimate of absolute concentration (switch at 200nM) was obtained by comparing fluorescent intensities of purified RFPt and cells under a spinning disk microscope while keeping the exact same acquisition settings. The whole procedure will be described in a manuscript in preparation, focused on Rac1 GEFs.

-

-

eLife Assessment

This important study combines compelling experiments with optogenetic actuation and convincing theory to understand how signalling proteins control the switch between cell protrusion and retraction, two essential processes in single cell migration. The authors examine the importance of the basal concentration and recruitment dynamics of a guanine exchange factor (GEF) on the activity of the downstream effectors RhoA and Cdc42, which control retraction and protrusion. The experimental and theoretical evidence provides a model of RhoA's involvment in both protrusion and retraction and shows that these complex processes are highly dependent on the concentration and activity dynamics of the components.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

De Seze et al. investigated the role of guanine exchange factors (GEFs) in controlling cell protrusion and retraction. In order to causally link protein activities to the switch between the opposing cell phenotypes, they employed optogenetic versions of GEFs which can be recruited to the plasma membrane upon light exposure and activate their downstream effectors. Particularly the RhoGEF PRG could elicit both protruding and retracting phenotypes. Interestingly, the phenotype depended on the basal expression level of the optoPRG. By assessing the activity of RhoA and Cdc42, the downstream effectors of PRG, the mechanism of this switch was elucidated: at low PRG levels, RhoA is predominantly activated and leads to cell retraction, whereas at high PRG levels, both RhoA and Cdc42 are activated but PRG also …

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

De Seze et al. investigated the role of guanine exchange factors (GEFs) in controlling cell protrusion and retraction. In order to causally link protein activities to the switch between the opposing cell phenotypes, they employed optogenetic versions of GEFs which can be recruited to the plasma membrane upon light exposure and activate their downstream effectors. Particularly the RhoGEF PRG could elicit both protruding and retracting phenotypes. Interestingly, the phenotype depended on the basal expression level of the optoPRG. By assessing the activity of RhoA and Cdc42, the downstream effectors of PRG, the mechanism of this switch was elucidated: at low PRG levels, RhoA is predominantly activated and leads to cell retraction, whereas at high PRG levels, both RhoA and Cdc42 are activated but PRG also sequesters the active RhoA, therefore Cdc42 dominates and triggers cell protrusion. Finally, they create a minimal model that captures the key dynamics of this protein interaction network and the switch in cell behavior.

The conclusions of this study are strongly supported by data, harnessing the power of modelling and optogenetic activation. The minimal model captures well the dynamics of RhoA and Cdc42 activation and predicts that by changing the frequency of optogenetic activation one can switch between protruding and retracting behaviour in the same cell of intermediate optoPRG level. The authors are indeed able to demonstrate this experimentally albeit with a very low number of cells. A major caveat of this study is that global changes due to PRG overexpression cannot be ruled out. Also, a quantification of absolute protein concentration, which is notoriously difficult, would be useful to put the level of overexpression here in perspective with endogenous levels. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether in cases of protein overexpression in vivo such as cancer, PRG or other GEFs can activate alternative migratory behaviours.

Previous work has implicated RhoA in both protrusion and retraction depending on the context. The mechanism uncovered here provides a convincing explanation for this conundrum. In addition to PRG, optogenetic versions of two other GEFs, LARG and GEF-H1, were used which produced either only one phenotype or less response than optoPRG, underscoring the functional diversity of RhoGEFs. The authors chose transient transfection to achieve a large range of concentration levels and, to find transfected cells at low cell density, developed a small software solution (Cell finder), which could be of interest for other researchers.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

This manuscript builds from the interesting observation that local recruitment of the DHPH domain of the RhoGEF PRG can induce local retraction, protrusion, or neither. The authors convincingly show that these differential responses are tied to the level of expression of the PRG transgene. This response depends on the Rho-binding activity of the recruited PH domain and is associated with and requires (co?)-activation of Cdc42. This begs the question of why this switch in response occurs. The use a computational model to predict that the timing of protein recruitment can dictate the output of the response in cells expressing intermediate levels and found that, "While the majority of cells showed mixed phenotypes irrespectively of the activation pattern, in few cells (3 out of 90) we were able to …

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

This manuscript builds from the interesting observation that local recruitment of the DHPH domain of the RhoGEF PRG can induce local retraction, protrusion, or neither. The authors convincingly show that these differential responses are tied to the level of expression of the PRG transgene. This response depends on the Rho-binding activity of the recruited PH domain and is associated with and requires (co?)-activation of Cdc42. This begs the question of why this switch in response occurs. The use a computational model to predict that the timing of protein recruitment can dictate the output of the response in cells expressing intermediate levels and found that, "While the majority of cells showed mixed phenotypes irrespectively of the activation pattern, in few cells (3 out of 90) we were able to alternate the phenotype between retraction and protrusion several times at different places of the cell by changing the frequency while keeping the same total integrated intensity (Figure 6F and Supp Movie)."

Comments on the revised manuscript:

The authors have addressed the previous points and they have convincingly demonstrated that an optogenetically recruited PRG-GEF acts, as expected, as a GEF for RhoA. However, if this fragment is strongly over-expressed, it activates Cdc42, instead of RhoA. This appears to be due to sequestration of active RhoA by the overexpressed PRG-GEF.

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Public Review:

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Regarding reviewer #2 public review, we update here our answers to this public review with new analysis and modification done in the manuscript.

This manuscript is missing a direct phenotypic comparison of control cells to complement that of cells expressing RhoGEF2-DHPH at "low levels" (the cells that would respond to optogenetic stimulation by retracting); and cells expressing RhoGEF2-DHPH at "high levels" (the cells that would respond to optogenetic stimulation by protruding). In other words, the authors should examine cell area, the distribution of actin and myosin, etc in all three groups of cells (akin to the time zero data from figures 3 and 5, with a negative control). For example, does the basal …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Public Review:

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Regarding reviewer #2 public review, we update here our answers to this public review with new analysis and modification done in the manuscript.

This manuscript is missing a direct phenotypic comparison of control cells to complement that of cells expressing RhoGEF2-DHPH at "low levels" (the cells that would respond to optogenetic stimulation by retracting); and cells expressing RhoGEF2-DHPH at "high levels" (the cells that would respond to optogenetic stimulation by protruding). In other words, the authors should examine cell area, the distribution of actin and myosin, etc in all three groups of cells (akin to the time zero data from figures 3 and 5, with a negative control). For example, does the basal expression meaningfully affect the PRG low-expressing cells before activation e.g. ectopic stress fibers? This need not be an optogenetic experiment, the authors could express RhoGEF2DHPH without SspB (as in Fig 4G).

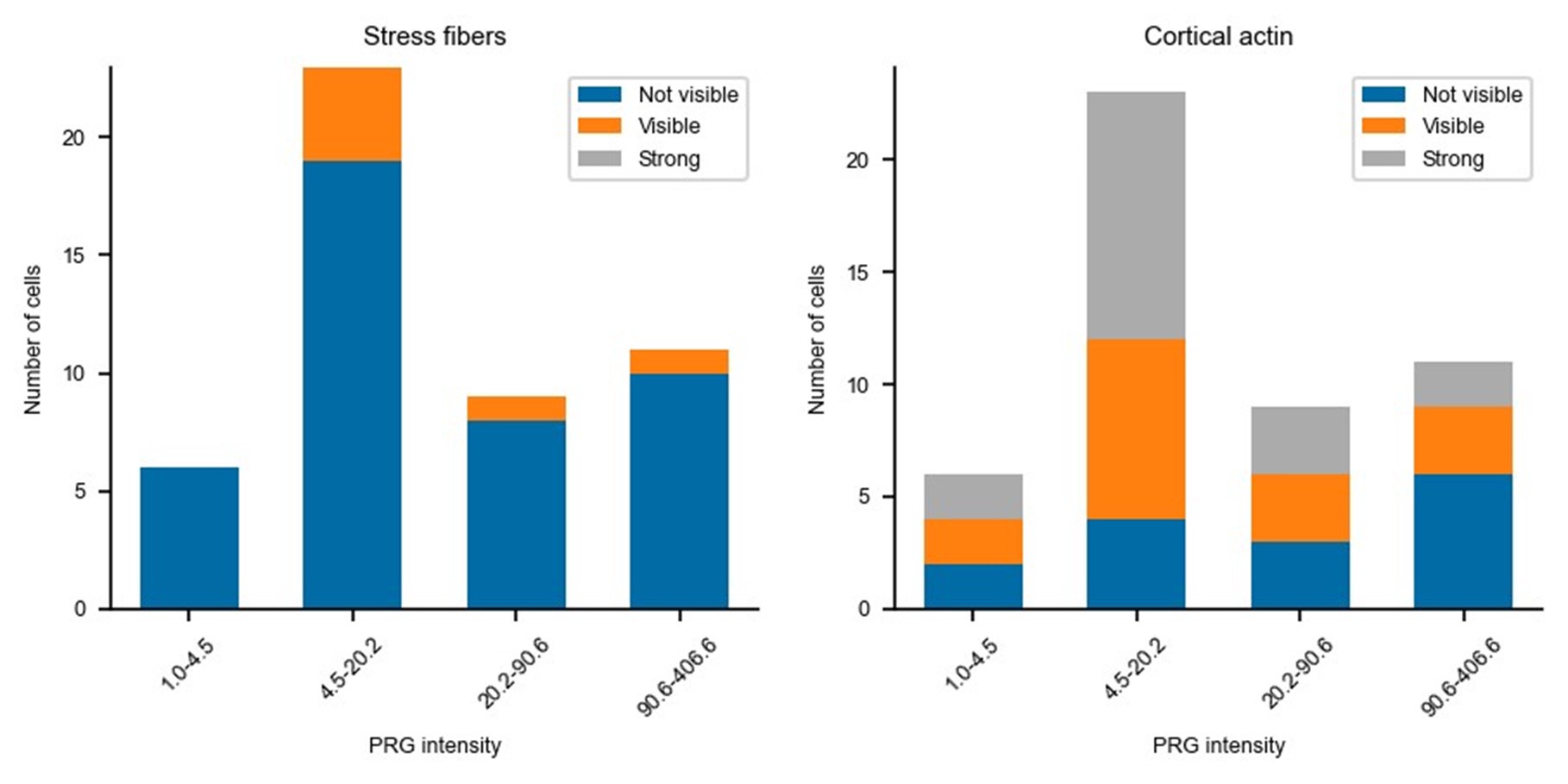

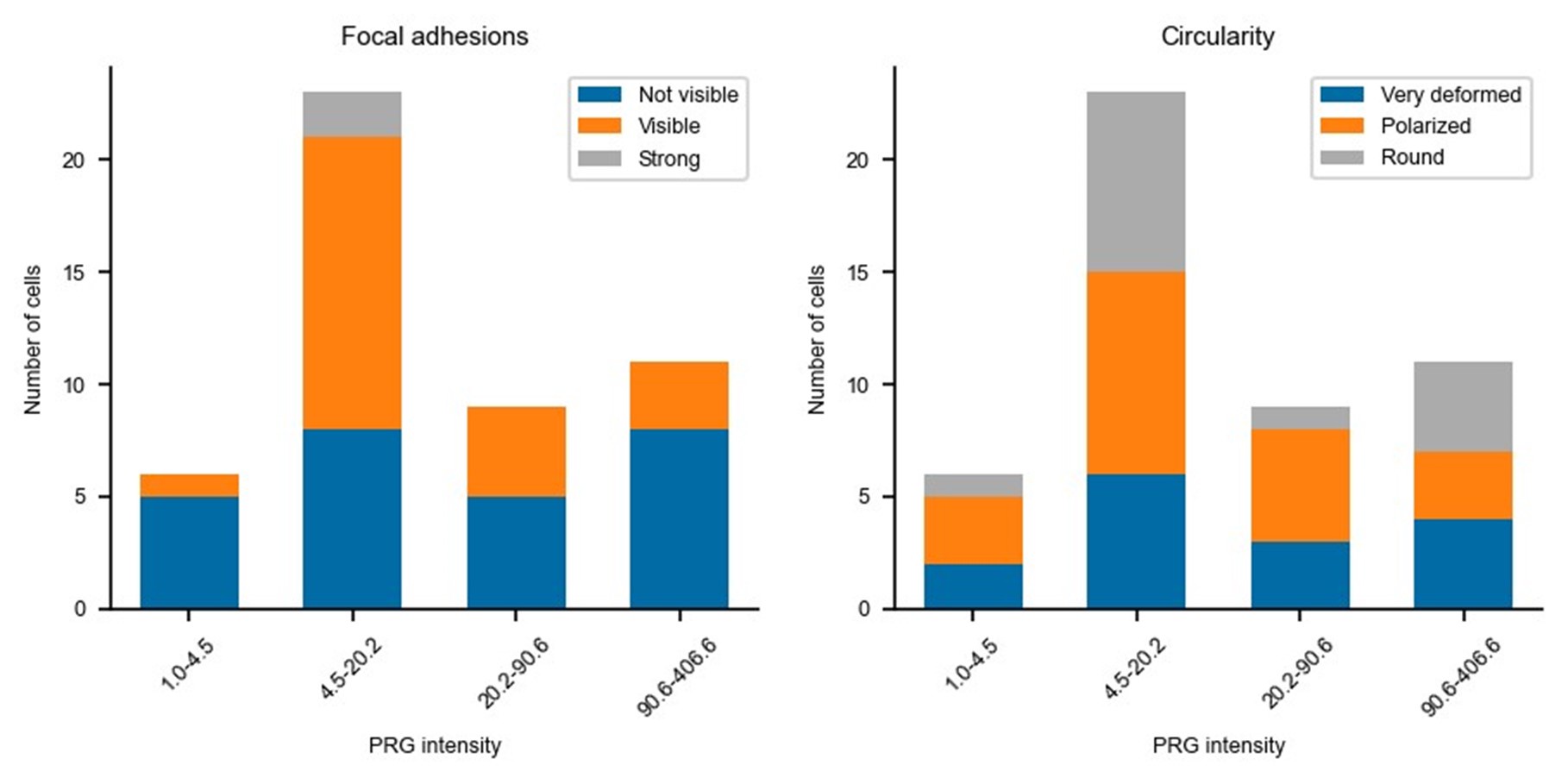

Updated answer: We thank reviewer #2 for this suggestion. PRG-DHPH overexpression is known to affect the phenotype of the cell as shown in Valon et al., 2017. In our experiments, we could not identify any evidence of a particular phenotype before optogenetic activation apart from the area and spontaneous membrane speed that were already reported in our manuscript (Fig 2E and SuppFig 2). Regarding the distribution of actin and myosin, we did not observe an obvious pattern that will be predictive of the protruding/retracting phenotype. Trying to be more quantitative, we have classified (by eye, without knowing the expression level of PRG nor the future phenotype) the presence of stress fibers, the amount of cortical actin, the strength of focal adhesions, and the circularity of cells. As shown below, when these classes are binned by levels of expression of PRG (two levels below the threshold and two above) there is no clear determinant. Thus, we concluded that the main driver of the phenotype was the PRG basal expression rather than any particularity of the actin cytoskeleton/cell shape.

Author response image 1.

Author response image 2.

Relatedly, the authors seem to assume ("recruitment of the same DH-PH domain of PRG at the membrane, in the same cell line, which means in the same biochemical environment." supplement) that the only difference between the high and low expressors are the level of expression. Given the chronic overexpression and the fact that the capacity for this phenotypic shift is not recruitmentdependent, this is not necessarily a safe assumption. The expression of this GEF could well induce e.g. gene expression changes.

Updated answer: We agree with reviewer #2 that there could be changes in gene expression. In the next point of this supplementary note, we had specified it, by saying « that overexpression has an influence on cell state, defined as protein basal activity or concentration before activation. » We are sorry if it was not clear, and we changed this sentence in the revised manuscript (in red in the supp note).

One of the interests of the model is that it does not require any change in absolute concentrations, beside the GEF. The model is thought to be minimal and fits well and explains the data with very few parameters. We do not show that there is no change in concentration, but we show that it is not required to invoke it. We revised a sentence in the new version of the manuscript to include this point.

Additional answer: During the revision process, we have been looking for an experimental demonstration of the independence of the phenotypic switch to any change in global gene expression pattern due to the chronic overexpression of PRG. Our idea was to be in a condition of high PRG overexpression such that cells protrude upon optogenetic activation, and then acutely deplete PRG to see if cells where then retracting. To deplete PRG in a timescale that prevent any change of gene expression, we considered the recently developed CATCHFIRE (PMID: 37640938) chemical dimerizer. We designed an experiment in which the PRG DH-PH domain was expressed in fusion with a FIRE-tag and co-expressing the FIRE-mate fused to TOM20 together with the optoPRG tool. Upon incubation with the MATCH small molecule, we should be able to recruit the overexpressed PRG to the mitochondria within minutes, hereby preventing it to form a complex with active RhoA in the vicinity of the plasma membrane. Unfortunately, despite of numerous trials we never achieved the required conditions: we could not have cells with high enough expression of PRGFIRE-tag (for protrusive response) and low enough expression of optoPRG (for retraction upon PRGFIRE-tag depletion). We still think this would be a nice experiment to perform, but it will require the establishment of a stable cell line with finely tuned expression levels of the CATCHFIRE system that goes beyond the timeline of our present work.

Concerning the overall model summarizing the authors' observations, they "hypothesized that the activity of RhoA was in competition with the activity of Cdc42"; "At low concentration of the GEF, both RhoA and Cdc42 are activated by optogenetic recruitment of optoPRG, but RhoA takes over. At high GEF concentration, recruitment of optoPRG lead to both activation of Cdc42 and inhibition of already present activated RhoA, which pushes the balance towards Cdc42."

These descriptions are not precise. What is the nature of the competition between RhoA and Cdc42? Is this competition for activation by the GEFs? Is it a competition between the phenotypic output resulting from the effectors of the GEFs? Is it competition from the optogenetic probe and Rho effectors and the Rho biosensors? In all likelihood, all of these effects are involved, but the authors should more precisely explain the underlying nature of this phenotypic switch. Some of these points are clarified in the supplement, but should also be explicit in the main text.

Updated answer: We consider the competition between RhoA and Cdc42 as a competition between retraction due to the protein network triggered by RhoA (through ROCK-Myosin and mDia-bundled actin) and the protrusion triggered by Cdc42 (through PAK-Rac-ARP2/3-branched Actin). We made this point explicit in the main text.

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations For The Authors):

Major

- why this is only possible for such few cells. Can the authors comment on this in the discussion? Does the model provide any hints?

As said in our answer to the public comment or reviewer #1, we think that the low number of cells being able to switch can be explained by two different reasons:

(1) First, we were looking for clear inversions of the phenotype, where we could see clear ruffles in the case of the protrusion, and clear retractions in the other case. Thus, we discarded cells that would show in-between phenotypes, because we had no quantitative parameter to compare how protrusive or retractile they were. This reduced the number of switching cells

(2) Second, we had a limitation due to the dynamic of the optogenetic dimer used here. Indeed, the control of the frequency was limited by the dynamic of unbinding of the optogenetic dimer. This dynamic of recruitment (~20s) is comparable to the dynamics of the deactivation of RhoA and Cdc42. Thus, the differences in frequency are smoothed and we could not vary enough the frequency to increase the number of switches. Thanks to the model, we can predict that increasing the unbinding rate of the optogenetic tool (shorter dimer lifetime) should allow us to increase the number of switching cells.

We have added a sentence in the discussion to make this second point explicit.

- I would encourage the authors to discuss this molecular signaling switch in the context of general design principles of switches. How generalizable is this network/mechanism? Is it exclusive to activating signaling proteins or would it work with inhibiting mechanisms? Is the competition for the same binding site between activators and effectors a common mechanism in other switches?

The most common design principle for molecular switches is the bistable switch that relies on a nonlinear activation (for example through cooperativity) with a linear deactivation. Such a design allows the switch between low and high levels. In our case, there is no need for a non-linearity since the core mechanism is a competition for the same binding site on active RhoA of the activator and the effectors. Thus, the design principle would be closer to the notion of a minimal “paradoxical component” (PMID: 23352242) that both activate and limit signal propagation, which in our case can be thought as a self-limiting mechanism to prevent uncontrolled RhoA activation by the positive feedback. Yet, as we show in our work, this core mechanism is not enough for the phenotypic switch to happen since the dual activation of RhoA and Cdc42 is ultimately required for the protrusion phenotype to take over the retracting one. Given the particularity of the switch we observed here, we do not feel comfortable to speculate on any general design principles in the main text, but we thank reviewer #1 for his/her suggestion.

- Supplementary figures - there is a discrepancy between the figures called in the text and the supplementary files, which only include SF1-4.

We apologize for this error and we made the correction.

- In the text, the authors use Supp Figure 7 to show that the phenotype could not be switched by varying the fold increase of recruitment through changing the intensity/duration of the light pulse. Aside from providing the figure, could you give an explanation or speculation of why? Does the model give any prediction as to why this could be difficult to achieve experimentally (is the range of experimentally feasible fold change of 1.1-3 too small? Also, could you clarify why the range is different than the 3 to 10-fold mentioned at the beginning of the results section?

We thank the reviewer for this question, and this difference between frequency and intensity can be indeed understood in a simple manner through the model.

All the reactions in our model were modeled as linear reactions. Thus, at any timepoint, changing the intensity of the pulse will only change proportionally the amount of the different components (amount of active RhoA, amount of sequestered RhoA, and amount of active Cdc42). This explains why we cannot change the balance between RhoA activity and Cdc42 activity only through the pulse strength. We observed the same experimentally: when we changed the intensity of the pulses, the phenotype would be smaller/stronger, but would never switch, supporting our hypothesis on the linearity of all biochemical reactions.

On the contrary, changing the frequency has an effect, for a simple reason: the dynamics of RhoA and Cdc42 activation are not the same as the dynamics of inhibition of RhoA by the PH domain (see

Figure 4). The inhibition of RhoA by the PH is almost instantaneous while the activation of RhoGTPases has a delay (sets by the deactivation parameter k_2). Intuitively, increasing the frequency will lead to sustained inhibition of RhoA, promoting the protrusion phenotype. Decreasing the frequency – with a stronger pulse to keep the same amount of recruited PRG – restricts this inhibition of RhoA to the first seconds following the activation. The delayed activation of RhoA will then take over.

We added two sentences in the manuscript to explain in greater details the difference between intensity and frequency.

Regarding the difference between the 1.3-3 fold and the 3 to 10 fold, the explanation is the following: the 3 to 10 fold referred to the cumulative amount of proteins being recruited after multiple activations (steady state amount reached after 5 minutes with one activation every 30s); while the 1.3-3 fold is what can be obtained after only one single pulse of activation.

- The transient expression achieves a large range of concentration levels which is a strength in this case. To solve the experimental difficulties associated with this, i.e. finding transfected cells at low cell density, the authors developed a software solution (Cell finder). Since this approach will be of interest for a wide range of applications, I think it would deserve a mention in the discussion part.

We thank the reviewer for his/her interest in this small software solution.

We developed the description of the tool in the Method section. The Cell finder is also available with comments on github (https://github.com/jdeseze/cellfinder) and usable for anyone using Metamorph or Micromanager imaging software.

Minor

- Can the authors describe what they mean with "cell state"? It is used multiple times in the manuscript and can be interpreted as various things.

We now explain what we mean by ‘cell state’ in the main text :

“protein basal activities and/or concentrations - which we called the cell state”

- “(from 0% to 45%, Figure 2D)", maybe add here: "compare also with Fig. 2A".

We completed the sentence as suggested, which clarifies the data for the readers.

- The sentence "Given that the phenotype switch appeared to be controlled by the amount of overexpressed optoPRG, we hypothesized that the corresponding leakiness of activity could influence the cell state prior to any activation." might be hard to understand for readers unfamiliar with optogenetic systems. I suggest adding a short sentence explaining dark-state activity/leakiness before putting the hypothesis forward.

We changed this whole beginning of the paragraph to clarify.

- Figure 2E and SF2A. I would suggest swapping these two panels as the quantification of the membrane displacement before activation seems more relevant in this context.

We thank reviewer #1 for this suggestion and we agree with it (we swapped the two panels)

- Fig. 2B is missing the white frames in the mixed panels.

We are sorry for this mistake, we changed it in the new version.

- In the text describing the experiment of Fig. 4G, it would again be helpful to define what the authors mean by cell state, or to state the expected outcome for both hypotheses before revealing the result.

We added precisions above on what we meant by cell state, which is the basal protein activities and/or concentrations prior to optogenetic activation. We added the expectation as follow:

To discriminate between these two hypotheses, we overexpressed the DH-PH domain alone in another fluorescent channel (iRFP) and recruited the mutated PH at the membrane. “If the binding to RhoA-GTP was only required to change the cell state, we would expect the same statistics than in Figure 2D, with a majority of protruding cells due to DH-PH overexpression. On the contrary, we observed a large majority of retracting phenotype even in highly expressing cells (Figure 4G), showing that the PH binding to RhoA-GTP during recruitment is a key component of the protruding phenotype.”

- Figure 4H,I: "of cells that overexpress PRG, where we only recruit the PH domain" doesn't match with the figure caption. Are these two constructs in the same cell? If not please clarify the main text.

We agree that it was not clear. Both constructs are in the same cell, and we changed the figure caption accordingly.

- "since RhoA dominates Cdc42" is this concluded from experiments (if yes, please refer to the figure) or is this known from the literature (if yes, please cite).

The assumption that RhoA dominates Cdc42 comes from the fact that we see retraction at low PRG concentration. We assumed that RhoA is responsible for the retraction phenotype. Our assumption is based on the literature (Burridge 2004 as an example of a review, confirmed by many experiments, such as the direct recruitment of RhoA to the membrane, see Berlew 2021) and is supported by our observations of immediate increase of RhoA activity at low PRG. We modified the text to clarify it is an assumption.

- Fig. 6G o left: is not intuitive, why are the number of molecules different to start with?

The number of molecules is different because they represent the active molecules: increasing the amount of PRG increases the amount of active RhoA and active Cdc42. We updated the figure to clarify this point.

o right: the y-axis label says "phenotype", maybe change it to "activity" or add a second y-axis on the right with "phenotype"?

We updated the figure following reviewer #1 suggestion.

- Discussion: "or a retraction in the same region" sounds like in the same cell. Perhaps rephrase to state retraction in a similar region?

Sorry for the confusion, we change it to be really clear: “a protrusion in the activation region when highly expressed, or a retraction in the activation region when expressed at low concentrations.”

Typos:

- "between 3 and 10 fold" without s.

- Fig. 1H, y-axis label.

- "whose spectrum overlaps" with s.

- "it first decays, and then rises" with s.

- Fig 4B and Fig 6B. Is the time in sec or min? (Maybe double-check all figures).

- "This result suggests that one could switch the phenotype in a single cell by selecting it for an intermediate expression level of the optoPRG.".

- "GEF-H1 PH domain has almost the same inhibition ability as PRG PH domain".

We corrected all these mistakes and thank the reviewer for his careful reading of the manuscript.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations For The Authors):

Likewise, the model assumes that at high PRG GEF expression, the "reaction is happening far from saturation ..." and that "GTPases activated with strong stimuli -giving rise to strong phenotypic changes- lead to only 5% of the proteins in a GTP-state, both for RhoA and Cdc42". Given the high levels of expression (the absolute value of which is not known) this assumption is not necessarily safe to assume. The shift to Cdc42 could indeed result from the quantitative conversion of RhoA into its active state.

We agree with the reviewer that the hypothesis that RhoA is fully converted into its active state cannot be completely ruled out. However, we think that the two following points can justify our choice.

- First, we see that even in the protruding phenotype, RhoA activity is increasing upon optoPRG recruitment (Figure 3). This means that RhoA is not completely turned into its active GTP-loaded state. The biosensor intensity is rising by a factor 1.5 after 5 minutes (and continue to increase, even if not shown here). For sure, it could be explained by the relocation of RhoA to the place of activation, but it still shows that cells with high PRG expression are not completely saturated in RhoA-GTP.

- We agree that linearity (no saturation) is still an hypothesis and very difficult to rule out, because it is not only a question of absolute concentrations of GEFs and RhoA, but also a question of their reaction kinetics, which are unknow parameters in vivo. Yet, adding a saturation parameter would mean adding 3 unknown parameters (absolute concentrations of RhoA, as well as two reaction constants). The fact that there are not needed to fit the complex curves of RhoA as we do with only one parameter tends to show that the minimal ingredients representing the interaction are captured here.

The observed "inhibition of RhoA by the PH domain of the GEF at high concentrations" could result from the ability of the probe to, upon membrane recruitment, bind to active RhoA (via its PH domain) thereby outcompeting the RhoA biosensor (Figure 4A-C). This reaction is explicitly stated in the supplemental materials ("PH domain binding to RhoA-GTP is required for protruding phenotype but not sufficient, and it is acting as an inhibitor of RhoA activity."), but should be more explicit in the main text. Indeed, even when PRG DHPH is expressed at high concentrations, it does activate RhoA upon recruitment (figure 3GH). Not only might overexpression of this active RhoA-binding probe inhibit the cortical recruitment of the RhoA biosensor, but it may also inhibit the ability of active RhoA to activate its downstream effectors, such as ROCK, which could explain the decrease in myosin accumulation (figure 3D-F). It is not clear that there is a way to clearly rule this out, but it may impact the interpretation.

This hypothesis is actually what we claim in the manuscript. We think that the inhibition of RhoA by the PH domain is explained by its direct binding. We may have missed what Reviewer #2 wanted to say, but we think that we state it explicitly in the main text :

“Knowing that the PH domain of PRG triggers a positive feedback loop thanks to its binding to active RhoA 18, we hypothesized that this binding could sequester active RhoA at high optoPRG levels, thus being responsible for its inhibition.”

And also in the Discussion:

“However, this feedback loop can turn into a negative one for high levels of GEF: the direct interaction between the PH domain and RhoA-GTP prevents RhoA-GTP binding to effectors through a competition for the same binding site.”

We may have not been clear, but we think that this is what is happening: the PH domain prevents the binding to effectors and decreases RhoA activity (as was shown in Chen et al. 2010).

The X-axis in Figure 4C time is in seconds not minutes. The Y-axis in Figure 4H is unlabeled.

We are sorry for the mistake of Figure 4C. We changed the Y-axis in the Figure 4h.

Although this publication cites some of the relevant prior literature, it fails to cite some particularly relevant works. For example, the authors state, "The LARG DH domain was already used with the iLid system" and refers to a 2018 paper (ref 19), whereas that domain was first used in 2016 (PMID 27298323). Indeed, the authors used the plasmid from this 2016 paper to build their construct.

We thank the reviewer for pointing out this error, we have corrected the citation and put the seminal one in the revised version.

An analogous situation pertains to previous work that showed that an optogenetic probe containing the DH and PH domains in RhoGEF2 is somewhat toxic in vivo (table 6; PMID 33200987). Furthermore, it has previously been shown that mutation of the equivalent of F1044A and I1046E eliminates this toxicity (table 6; PMID 33200987) in vivo. This is particularly important because the Rho probe expressing RhoGEF2-DHPH is in widespread usage (76 citations in PubMed). The ability of this probe to activate Cdc42 may explain some of the phenotypic differences described resulting from the recruitment of RhoGEF2-DHPH and LARG-DH in a developmental context (PMID 29915285, 33200987).

We thank reviewer #2 for these comments, and added a small section in the discussion, for optogenetic users:

This underlines the attention that needs to be paid to the choice of specific GEF domains when using optogenetic tools. Tools using DH-PH domains of PRG have been widely used, both in mammalian cells and in Drosophila (with the orthologous gene RhoGEF2), and have been shown to be toxic in some contexts in vivo 28. Our study confirms the complex behavior of this domain which cannot be reduced to a simple RhoA activator.

Concerning the experiment shown in 4D, it would be informative to repeat this experiment in which a non-recruitable DH-PH domain of PRG is overexpressed at high levels and the DH domain of LARG is recruited. This would enable the authors to distinguish whether the protrusion response is entirely dependent on the cell state prior to activation or the combination of the cell state prior to activation and the ability of PRG DHPH to also activate Cdc42.

We thank the reviewer for his suggestion. Yet, we think that we have enough direct evidence that the protruding phenotype is due to both the cell state prior to activation and the ability of PRG DHPH to also activate Cdc42. First, we see a direct increase in Cdc42 activity following optoPRG recruitment (see Figure 6). This increase is sustained in the protruding phenotype and precedes Rac1 and RhoA activity, which shows that it is the first of these three GTPases to be activated. Moreover, we showed that inhibition of PAK by the very specific drug IPA3 is completely abolishing only the protruding phenotype, which shows that PAK, a direct effector of Cdc42 and Rac1, is required for the protruding phenotype to happen. We know also that the cell state prior to activation is defining the phenotype, thanks to the data presented in Figure 2.

We further showed in Figure 1 that LARG DH-PH domain was not able to promote protrusion. The proposed experiment would be interesting to confirm that LARG does not have the ability to activate another GTPase, even in a different cell state with overexpressed PRG. However, we are not sure it would bring any substantial findings to understand the mechanism we describe here, given the facts provided above.

Similarly, as PRG activates both Cdc42 and Rho at high levels, it would be important to determine the extent to which the acute Rho activation contributes to the observed phenotype (e.g. with Rho kinase inhibitor).

We agree with the reviewer that it would be interesting to know whether RhoA activation contributes to the observed phenotype, and we have tried such experiments.

For Rho kinase inhibitor, we tried with Y-27632 and we could never prevent the protruding phenotype to happen. However, we could not completely abolish the retracting phenotype either (even when the effect on the cells was quite strong and visible), which could be due to other effectors compensating for this inhibition. As RhoA has many other effectors, it does not tell us that RhoA is not required for protrusion.

We also tried with C3, which is a direct inhibitor of RhoA. However, it had too much impact on the basal state of the cells, making it impossible to recruit (cells were becoming round and clearly dying. As both the basal state and optogenetic activation require the activation of RhoA, it is hard to conclude out of experiments where no cell is responding.

The ability of PRG to activate Cdc42 in vivo is striking given the strong preference for RhoA over Cdc42 in vitro (2400X) (PMID 23255595). Is it possible that at these high expression levels, much of the RhoA in the cell is already activated, so that the sole effect that recruited PRG can induce is activation of Cdc42? This is related to the previous point pertaining to absolute expression levels.

As discussed before, we think that it is not only a question of absolute expression levels, but also of the affinities between the different partners. But Reviewer #2 is right, there is a competition between the activation of RhoA and Cdc42 by optoPRG, and activation of Cdc42 probably happens at higher concentration because of smaller effective affinity.

Still, we know that activation of the Cdc42 by PRG DH-PH domain is possible in vivo, as it was very clearly shown in Castillo-Kauil et al., 2020 (PMID 33023908). They show that this activation requires the linker between DH and PH domain of PRG, as well as Gαs activation, which requires a change in PRG DH-PH conformation. This conformational switch does not happen in vitro, which might explain why the affinity against Cdc42 was found to be very low.

Minor points

In both the abstract and the introduction the authors state, "we show that a single protein can trigger either protrusion or retraction when recruited to the plasma membrane, polarizing the cell in two opposite directions." However, the cells do not polarize in opposite directions, ie the cells that retract do not protrude in the direction opposite the retraction (or at least that is not shown). Rather a single protein can trigger either protrusion or retraction when recruited to the plasma membrane, depending upon expression levels.

We thank the reviewer for this remark, and we agree that we had not shown any data supporting a change in polarization. We solved this issue, by showing now in Supplementary Figure 1 the change in areas in both the activated and in the not activated region. The data clearly show that when a protrusion is happening, the cell retracts in the non-activated region. On the other hand, when the cell retracts, a protrusion happens in the other part of the cell, while the total area is staying approximately constant.

We added the following sentence to describe our new figure:

Quantification of the changes in membrane area in both the activated and non-activated part of the cell (Supp Figure 1B-C) reveals that the whole cell is moving, polarizing in one direction or the other upon optogenetic activation.

While the authors provide extensive quantitative data in this manuscript and quantify the relative differences in expression levels that result in the different phenotypes, it would be helpful to quantify the absolute levels of expression of these GEFs relative to e.g. an endogenously expressed GEF.

We agree with the reviewer comment, and we also wanted to have an idea of the absolute level of expression of GEFs present in these cells to be able to relate fluorescent intensities with absolute concentrations. We tried different methods, especially with the purified fluorescent protein, but having exact numbers is a hard task.

We ended up quantifying the amount of fluorescent protein within a stable cell line thanks to ELISA and comparing it with the mean fluorescence seen under the microscope.

We estimated that the switch concentration was around 200nM, which is 8 times more than the mean endogenous concentration according to https://opencell.czbiohub.org/, but should be reachable locally in wild type cell, or globally in mutated cancer cells.

Given the numerical data (mostly) in hand, it would be interesting to determine whether RhoGEF2 levels, cell area, the pattern of actin assembly, or some other property is most predictive of the response to PRG DHPH recruitment.

We think that the manuscript made it clear that the concentration of PRG DHPH is almost 100% predictive of the response to PRG DHPH. We believe that other phenotypes such as the cell area or the pattern of actin assembly would only be consequences of this. Interestingly, as experimentators we were absolutely not able to predict the behavior by only seeing the shape of the cell, event after hundreds of activation experiments, and we tried to find characteristics that would distinguish both populations with the data in our hands and could not find any.

There is some room for general improvement/editing of the text.

We tried our best to improve the text, following reviewers suggestions.

-

Author Response

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

De Seze et al. investigated the role of guanine exchange factors (GEFs) in controlling cell protrusion and retraction. In order to causally link protein activities to the switch between the opposing cell phenotypes, they employed optogenetic versions of GEFs which can be recruited to the plasma membrane upon light exposure and activate their downstream effectors. Particularly the RhoGEF PRG could elicit both protruding and retracting phenotypes. Interestingly, the phenotype depended on the basal expression level of the optoPRG. By assessing the activity of RhoA and Cdc42, the downstream effectors of PRG, the mechanism of this switch was elucidated: at low PRG levels, RhoA is predominantly activated and leads to cell retraction, whereas at high PRG levels, both RhoA and Cdc42 are activated …

Author Response

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

De Seze et al. investigated the role of guanine exchange factors (GEFs) in controlling cell protrusion and retraction. In order to causally link protein activities to the switch between the opposing cell phenotypes, they employed optogenetic versions of GEFs which can be recruited to the plasma membrane upon light exposure and activate their downstream effectors. Particularly the RhoGEF PRG could elicit both protruding and retracting phenotypes. Interestingly, the phenotype depended on the basal expression level of the optoPRG. By assessing the activity of RhoA and Cdc42, the downstream effectors of PRG, the mechanism of this switch was elucidated: at low PRG levels, RhoA is predominantly activated and leads to cell retraction, whereas at high PRG levels, both RhoA and Cdc42 are activated but PRG also sequesters the active RhoA, therefore Cdc42 dominates and triggers cell protrusion. Finally, they create a minimal model that captures the key dynamics of this protein interaction network and the switch in cell behavior.

We thank reviewer #1 for this assessment of our work.

The conclusions of this study are strongly supported by data. Perhaps the manuscript could include some further discussion to for example address the low number of cells (3 out of 90) that can be switched between protrusion and retraction by varying the frequency of the light pulses to activate opto-PRG.

The low number of cells being able to switch can be explained by two different reasons:

first, we were looking for clear inversions of the phenotype, where we could see clear ruffles in the case of the protrusion, and clear retractions in the other case. Thus, we discarded cells that would show in-between phenotypes, because we had no quantitative parameter to compare how protrusive or retractile they were. This reduced the number of switching cells

second, we had a limitation due to the dynamic of the optogenetic dimer used here. Indeed, the control of the frequency was limited by the dynamic of unbinding of the optogenetic dimer. This dynamic of recruitment (~20s) is comparable to the dynamics of the deactivation of RhoA and Cdc42. Thus, the differences in frequency are smoothed and we could not vary enough the frequency to increase the number of switches. Thanks to the model, we can predict that decreasing the unbinding rate of the optogenetic tool should allow us to increase the number of switching cells.

We will add further discussion of this aspect to the manuscript.

Also, the authors could further describe their "Cell finder" software solution that allows the identification of positive cells at low cell density, as this approach will be of interest for a wide range of applications.

There is a detailed explanation of the ‘Cell finder’ in the method sections. It is also available on github at https://github.com/jdeseze/cellfinder and currently in development to be more user-friendly and properly commented.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Summary:

This manuscript builds from the interesting observation that local recruitment of the DHPH domain of the RhoGEF PRG can induce local retraction, protrusion, or neither. The authors convincingly show that these differential responses are tied to the level of expression of the PRG transgene. This response depends on the Rho-binding activity of the recruited PH domain and is associated with and requires (co?)-activation of Cdc42. This begs the question of why this switch in response occurs. They use a computational model to predict that the timing of protein recruitment can dictate the output of the response in cells expressing intermediate levels and found that, "While the majority of cells showed mixed phenotypes irrespectively of the activation pattern, in few cells (3 out of 90) we were able to alternate the phenotype between retraction and protrusion several times at different places of the cell by changing the frequency while keeping the same total integrated intensity (Figure 6F and Supp Movie)."

Strengths:

The experiments are well-performed and nicely documented. However, the molecular mechanism underlying the shift in response is not clear (or at least clearly described). In addition, it is not clear that a prediction that is observed in ~3% of cells should be interpreted as confirming a model, though the fit to the data in 6B is impressive.

Overall, the main general biological significance of this work is that RhoGEF can have "off target effects". This finding is significant in that an orthologous GEF is widely used in optogenetic experiments in drosophila. It's possible that these findings may likewise involve phenotypes that reflect the (co-)activation of other Rho family GTPases.

We thank reviewer #2 for having assessed our work. Indeed, the main finding of this work is the change in the GEF function upon its change in concentration, which could be explained with a simple model supported by quantitative data. We think that the mechanism of the switch is quite clear, supported by the data showing the double effect of the PH domain and the activation of Cdc42. The few cells that are able to switch phenotype have to be seen as an honest data confirming that 1) concentration is indeed the main determinant of the protein’s function, and the switch is hard to obtain (which is also predicted by the model) 2) the two underlying networks are being activated at different timescales, which leaves some space for differential activation in the same cell. We are here limited by the dynamic of the optogenetic tool, as explained in the response to reviewer #1, and the intrinsic cell-to-cell variability.

Regarding the interpretation of our results as RhoGEF “off target effects”, we think that it might be too reductive. As said in the discussion, we proposed that the dual role of the RhoGEF could have physiological implications on the induction of front protrusions and rear retractions. While we do not demonstrate it here, it opens the door for further investigation.

Weaknesses:

The manuscript makes a number of untested assumptions and the underlying mechanism for this phenotypic shift is not clearly defined.

We may not have been clear in our manuscript, but we think that the underlying mechanism for this phenotypic shift is clearly explained and backed up by the data and the literature. It relies on 1) the ability of PRG to activate both RhoA and Cdc42 and 2) the ability of the PH domain to directly bind to active RhoA (which is, as shown in the manuscript, necessary but not sufficient for protrusions to happen). The model succeeds in reproducing the data of RhoA with only one free parameter and two independently fitted ones. The fact that activation of RhoA and Cdc42 lead to retraction and protrusion respectively is known since a long time. Thus, we think that the switch is clearly and quantitatively explained.

This manuscript is missing a direct phenotypic comparison of control cells to complement that of cells expressing RhoGEF2-DHPH at "low levels" (the cells that would respond to optogenetic stimulation by retracting); and cells expressing RhoGEF2-DHPH at "high levels" (the cells that would respond to optogenetic stimulation by protruding). In other words, the authors should examine cell area, the distribution of actin and myosin, etc in all three groups of cells (akin to the time zero data from figures 3 and 5, with a negative control). For example, does the basal expression meaningfully affect the PRG low-expressing cells before activation e.g. ectopic stress fibers? This need not be an optogenetic experiment, the authors could express RhoGEF2DHPH without SspB (as in Fig 4G).

We thank reviewer #2 for this suggestion. PRG-DHPH is known to affect the phenotype of the cell as shown in Valon et al., 2017. Thus, we really focused on the change implied by the change in optoPRG expression, to understand the phenotype difference. However, we agree that this could be an interesting data to add and will do the experiments for the revised version of the manuscript.

Relatedly, the authors seem to assume ("recruitment of the same DH-PH domain of PRG at the membrane, in the same cell line, which means in the same biochemical environment." supplement) that the only difference between the high and low expressors are the level of expression. Given the chronic overexpression and the fact that the capacity for this phenotypic shift is not recruitment-dependent, this is not necessarily a safe assumption. The expression of this GEF could well induce e.g. gene expression changes.

We agree with reviewer #2 that there could be changes in gene expression. In the next point of this supplementary note, we had specified it, by saying « that overexpression has an influence on cell state, defined as protein basal activity or concentration before activation. » We are sorry if it was not clear and will change this sentence for the new version.

One of the interests of the model is that it does not require any change in absolute concentrations, beside the GEF. The model is thought to be minimal and fits well and explains the data with very few parameters. We don’t show that there is no change in concentration but we show that it is not required to invoke it.

We will add in the revised version of the manuscript a paragraph discussing this question.

The third paragraph of the introduction, which begins with the sentence, "Yet, a large body of works on the regulation of GTPases has revealed a much more complex picture with numerous crosstalks and feedbacks allowing the fine spatiotemporal patterning of GTPase activities" is potentially confusing to readers. This paragraph suggests that an individual GTPase may have different functions whereas the evidence in this manuscript demonstrates, instead, that a particular GEF can have multiple activities because it can differentially activate two different GTPases depending on expression levels. It does not show that a particular GTPase has two distinct activities. The notion that a particular GEF can impact multiple GTPases is not particularly novel, though it is novel (to my knowledge) that the different activities depend on expression levels.

We thank the reviewer for this remark and didn’t intended to confuse the readers. Indeed, we think that this manuscript confirms the canonical view on the GTPases (as most optogenetic experiments did in the past years). We show here that it is more complicated at the level of the GEF. We agree that this is not particularly novel. However, to our knowledge, there is no example of such clear phenotypic control, explained solely by the change in concentration.

We think that the last paragraph of the introduction is quite clear in the fact that it is the GEF itself that switches its function, and not the Rho-GTPases, but we will reconsider the phrasing of this paragraph for the revised version.

Concerning the overall model summarizing the authors' observations, they "hypothesized that the activity of RhoA was in competition with the activity of Cdc42"; "At low concentration of the GEF, both RhoA and Cdc42 are activated by optogenetic recruitment of optoPRG, but RhoA takes over. At high GEF concentration, recruitment of optoPRG lead to both activation of Cdc42 and inhibition of already present activated RhoA, which pushes the balance towards Cdc42."

These descriptions are not precise. What is the nature of the competition between RhoA and Cdc42? Is this competition for activation by the GEFs? Is it a competition between the phenotypic output resulting from the effectors of the GEFs? Is it competition from the optogenetic probe and Rho effectors and the Rho biosensors? In all likelihood, all of these effects are involved, but the authors should more precisely explain the underlying nature of this phenotypic switch. Some of these points are clarified in the supplement, but should also be explicit in the main text.

We are going to precise these descriptions for the revised version of the manuscript. The competition between RhoA and Cdc42 was thought as a competition between retraction due to the protein network triggered by RhoA (through ROCK-Myosin and mDia-bundled actin) and the protrusion triggered by Cdc42 (through PAK-Rac-ARP2/3-branched Actin). We will make it explicit in the main text.

-

-

-

eLife assessment

This important study combines experiments with optogenetic actuation and theory to understand how signalling proteins control the switch between cell protrusion and retraction, two processes in single-cell migration. The authors examine the role of a guanine exchange factor (GEF) on the downstream effectors RhoA and Cdc42, which trigger retraction and protrusion, respectively. The experimental and theoretical evidence provides a convincing explanation for why and how a single signalling protein – here, a GEF of RhoA – can control both protrusion and retraction.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

De Seze et al. investigated the role of guanine exchange factors (GEFs) in controlling cell protrusion and retraction. In order to causally link protein activities to the switch between the opposing cell phenotypes, they employed optogenetic versions of GEFs which can be recruited to the plasma membrane upon light exposure and activate their downstream effectors. Particularly the RhoGEF PRG could elicit both protruding and retracting phenotypes. Interestingly, the phenotype depended on the basal expression level of the optoPRG. By assessing the activity of RhoA and Cdc42, the downstream effectors of PRG, the mechanism of this switch was elucidated: at low PRG levels, RhoA is predominantly activated and leads to cell retraction, whereas at high PRG levels, both RhoA and Cdc42 are activated but PRG also …

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

De Seze et al. investigated the role of guanine exchange factors (GEFs) in controlling cell protrusion and retraction. In order to causally link protein activities to the switch between the opposing cell phenotypes, they employed optogenetic versions of GEFs which can be recruited to the plasma membrane upon light exposure and activate their downstream effectors. Particularly the RhoGEF PRG could elicit both protruding and retracting phenotypes. Interestingly, the phenotype depended on the basal expression level of the optoPRG. By assessing the activity of RhoA and Cdc42, the downstream effectors of PRG, the mechanism of this switch was elucidated: at low PRG levels, RhoA is predominantly activated and leads to cell retraction, whereas at high PRG levels, both RhoA and Cdc42 are activated but PRG also sequesters the active RhoA, therefore Cdc42 dominates and triggers cell protrusion. Finally, they create a minimal model that captures the key dynamics of this protein interaction network and the switch in cell behavior.

The conclusions of this study are strongly supported by data. Perhaps the manuscript could include some further discussion to for example address the low number of cells (3 out of 90) that can be switched between protrusion and retraction by varying the frequency of the light pulses to activate opto-PRG. Also, the authors could further describe their "Cell finder" software solution that allows the identification of positive cells at low cell density, as this approach will be of interest for a wide range of applications.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Summary:

This manuscript builds from the interesting observation that local recruitment of the DHPH domain of the RhoGEF PRG can induce local retraction, protrusion, or neither. The authors convincingly show that these differential responses are tied to the level of expression of the PRG transgene. This response depends on the Rho-binding activity of the recruited PH domain and is associated with and requires (co?)-activation of Cdc42. This begs the question of why this switch in response occurs. They use a computational model to predict that the timing of protein recruitment can dictate the output of the response in cells expressing intermediate levels and found that, "While the majority of cells showed mixed phenotypes irrespectively of the activation pattern, in few cells (3 out of 90) we were able to …

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Summary:

This manuscript builds from the interesting observation that local recruitment of the DHPH domain of the RhoGEF PRG can induce local retraction, protrusion, or neither. The authors convincingly show that these differential responses are tied to the level of expression of the PRG transgene. This response depends on the Rho-binding activity of the recruited PH domain and is associated with and requires (co?)-activation of Cdc42. This begs the question of why this switch in response occurs. They use a computational model to predict that the timing of protein recruitment can dictate the output of the response in cells expressing intermediate levels and found that, "While the majority of cells showed mixed phenotypes irrespectively of the activation pattern, in few cells (3 out of 90) we were able to alternate the phenotype between retraction and protrusion several times at different places of the cell by changing the frequency while keeping the same total integrated intensity (Figure 6F and Supp Movie)."

Strengths:

The experiments are well-performed and nicely documented. However, the molecular mechanism underlying the shift in response is not clear (or at least clearly described). In addition, it is not clear that a prediction that is observed in ~3% of cells should be interpreted as confirming a model, though the fit to the data in 6B is impressive.

Overall, the main general biological significance of this work is that RhoGEF can have "off target effects". This finding is significant in that an orthologous GEF is widely used in optogenetic experiments in drosophila. It's possible that these findings may likewise involve phenotypes that reflect the (co-)activation of other Rho family GTPases.

Weaknesses:

The manuscript makes a number of untested assumptions and the underlying mechanism for this phenotypic shift is not clearly defined.

This manuscript is missing a direct phenotypic comparison of control cells to complement that of cells expressing RhoGEF2-DHPH at "low levels" (the cells that would respond to optogenetic stimulation by retracting); and cells expressing RhoGEF2-DHPH at "high levels" (the cells that would respond to optogenetic stimulation by protruding). In other words, the authors should examine cell area, the distribution of actin and myosin, etc in all three groups of cells (akin to the time zero data from figures 3 and 5, with a negative control). For example, does the basal expression meaningfully affect the PRG low-expressing cells before activation e.g. ectopic stress fibers? This need not be an optogenetic experiment, the authors could express RhoGEF2DHPH without SspB (as in Fig 4G).

Relatedly, the authors seem to assume ("recruitment of the same DH-PH domain of PRG at the membrane, in the same cell line, which means in the same biochemical environment." supplement) that the only difference between the high and low expressors are the level of expression. Given the chronic overexpression and the fact that the capacity for this phenotypic shift is not recruitment-dependent, this is not necessarily a safe assumption. The expression of this GEF could well induce e.g. gene expression changes.

The third paragraph of the introduction, which begins with the sentence, "Yet, a large body of works on the regulation of GTPases has revealed a much more complex picture with numerous crosstalks and feedbacks allowing the fine spatiotemporal patterning of GTPase activities" is potentially confusing to readers. This paragraph suggests that an individual GTPase may have different functions whereas the evidence in this manuscript demonstrates, instead, that *a particular GEF* can have multiple activities because it can differentially activate two different GTPases depending on expression levels. It does not show that a particular GTPase has two distinct activities. The notion that a particular GEF can impact multiple GTPases is not particularly novel, though it is novel (to my knowledge) that the different activities depend on expression levels.

These descriptions are not precise. What is the nature of the competition between RhoA and Cdc42? Is this competition for activation by the GEFs? Is it a competition between the phenotypic output resulting from the effectors of the GEFs? Is it competition from the optogenetic probe and Rho effectors and the Rho biosensors? In all likelihood, all of these effects are involved, but the authors should more precisely explain the underlying nature of this phenotypic switch. Some of these points are clarified in the supplement, but should also be explicit in the main text.

-

-

-

-