Measuring changes in Plasmodium falciparum census population size in response to sequential malaria control interventions

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

eLife Assessment

This valuable study highlights how the diversity of the malaria parasite population diminishes following the initiation of effective control interventions but quickly rebounds as control wanes. It also demonstrates that the asymptomatic reservoir is unevenly distributed across host age groups. The data presented are convincing and the work shows how genetic studies could be used to monitor changes in disease transmission.

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

Here, we introduce a new endpoint ‘census population size’ to evaluate the epidemiology and control of Plasmodium falciparum infections, where the parasite, rather than the infected human host, is the unit of measurement. To calculate census population size, we rely on a definition of parasite variation known as multiplicity of infection (MOI var ), based on the hyper-diversity of the var multigene family. We present a Bayesian approach to estimate MOI var from sequencing and counting the number of unique DBLα tags (or DBLα types) of var genes, and derive from it census population size by summation of MOI var in the human population. We track changes in this parasite population size and structure through sequential malaria interventions by indoor residual spraying (IRS) and seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) from 2012 to 2017 in an area of high, seasonal malaria transmission in northern Ghana. Following IRS, which reduced transmission intensity by >90% and decreased parasite prevalence by ~40–50%, significant reductions in var diversity, MOI var , and population size were observed in ~2000 humans across all ages. These changes, consistent with the loss of diverse parasite genomes, were short-lived and 32 months after IRS was discontinued and SMC was introduced, var diversity and population size rebounded in all age groups except for the younger children (1–5 years) targeted by SMC. Despite major perturbations from IRS and SMC interventions, the parasite population remained very large and retained the var population genetic characteristics of a high-transmission system (high var diversity; low var repertoire similarity), demonstrating the resilience of P. falciparum to short-term interventions in high-burden countries of sub-Saharan Africa.

Article activity feed

-

-

-

-

eLife Assessment

This valuable study highlights how the diversity of the malaria parasite population diminishes following the initiation of effective control interventions but quickly rebounds as control wanes. It also demonstrates that the asymptomatic reservoir is unevenly distributed across host age groups. The data presented are convincing and the work shows how genetic studies could be used to monitor changes in disease transmission.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

In this manuscript, Tiedje and colleagues longitudinally track changes in parasite number across four time points as a way of assessing the effect of malaria control interventions in Ghana. Some of the study results have been reported previously, and in this publication, the authors focus on age-stratification of the results. Malaria prevalence was lower in all age groups after IRS. Follow-up with SMC, however, maintained lower parasite prevalence in the targeted age group but not the population as a whole. Additionally, they observe that diversity measures rebound more slowly than prevalence measures. This adds to a growing literature that demonstrates the relevance of asymptomatic reservoirs.

Overall, I found these results clear, convincing, and well presented. There is growing interest in developing an …

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

In this manuscript, Tiedje and colleagues longitudinally track changes in parasite number across four time points as a way of assessing the effect of malaria control interventions in Ghana. Some of the study results have been reported previously, and in this publication, the authors focus on age-stratification of the results. Malaria prevalence was lower in all age groups after IRS. Follow-up with SMC, however, maintained lower parasite prevalence in the targeted age group but not the population as a whole. Additionally, they observe that diversity measures rebound more slowly than prevalence measures. This adds to a growing literature that demonstrates the relevance of asymptomatic reservoirs.

Overall, I found these results clear, convincing, and well presented. There is growing interest in developing an expanded toolkit for genomic epidemiology in malaria, and detecting changes in transmission intensity is one major application. As the authors summarize, there is no one-size-fits-all approach, and the Bayesian MOIvar estimate developed here has the potential to complement currently used methods, particularly in regions with high diversity/transmission. I find its extension to a calculation of absolute parasite numbers appealing as this could serve as both a conceptually straightforward and biologically meaningful metric.

As the authors address, their use of the term "census population size" is distinct from how the term is used in the population genetics literature. I therefore anticipate that parasite count will be most useful in an epidemiological context where the total number of sampled parasites can be contrasted with other metrics to help us better understand how parasites are divided across hosts, space, and time.

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

In this manuscript, Tiedje and colleagues longitudinally track changes in parasite numbers across four time points as a way of assessing the effect of malaria control interventions in Ghana. Some of the study results have been reported previously, and in this publication, the authors focus on age-stratification of the results. Malaria prevalence was lower in all age groups after IRS. Follow-up with SMC, however, maintained lower parasite prevalence in the targeted age group but not the population as a whole. Additionally, they observe that diversity measures rebound more slowly than prevalence measures. This adds to a growing literature that demonstrates the relevance of asymptomatic reservoirs.

Strengths:

Overall, I found these …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

In this manuscript, Tiedje and colleagues longitudinally track changes in parasite numbers across four time points as a way of assessing the effect of malaria control interventions in Ghana. Some of the study results have been reported previously, and in this publication, the authors focus on age-stratification of the results. Malaria prevalence was lower in all age groups after IRS. Follow-up with SMC, however, maintained lower parasite prevalence in the targeted age group but not the population as a whole. Additionally, they observe that diversity measures rebound more slowly than prevalence measures. This adds to a growing literature that demonstrates the relevance of asymptomatic reservoirs.

Strengths:

Overall, I found these results clear, convincing, and well-presented. There is growing interest in developing an expanded toolkit for genomic epidemiology in malaria, and detecting changes in transmission intensity is one major application. As the authors summarize, there is no one-size-fits-all approach, and the Bayesian MOIvar estimate developed here has the potential to complement currently used methods, particularly in regions with high diversity/transmission. I find its extension to a calculation of absolute parasite numbers appealing as this could serve as both a conceptually straightforward and biologically meaningful metric.

We thank the reviewer for this positive review of our results and approach.

Weaknesses:

While I understand the conceptual importance of distinguishing among parasite prevalence, mean MOI, and absolute parasite number, I am not fully convinced by this manuscript's implementation of "census population size".

This reviewer remains unconvinced of the use of the term “census population size”. This appears to be due to the dependence of the term on sample size rather than representing a count of a whole population. To give context to our use we are clear in the study presented that the term describes a count of the parasite “strains” in an age-specific sample of a human population in a specified location undergoing malaria interventions.

They have suggested instead using “sample parasite count”. We argue that this definition is too specific and less applicable when we extrapolate the same concept to a different denominator, such as the population in a given area. Importantly, our ecological use of a census allows us to count the appearance of the same strain more than once should this occur in different people.

The authors reference the population genetic literature, but within the context of that field, "census population size" refers to the total population size (which, if not formally counted, can be extrapolated) as opposed to "effective population" size, which accounts for a multitude of demographic factors. There is often interesting biology to be gleaned from the magnitude of difference between N and Ne.

As stated in the introduction we have been explicit in saying that we are not using a population genetic framework. Exploration of N and Ne in population genetics has merit. How this is reconciled when using a “strain” definition and not neutral markers would need to be assessed.

In this manuscript, however, "census population size" is used to describe the number of distinct parasites detected within a sample, not a population. As a result, the counts do not have an immediate population genetic interpretation and cannot be directly compared to Ne. This doesn't negate their usefulness but does complicate the use of a standard population genetic term.

We are clear we are defining a census of parasite strains in an age-specific sample of a population living in two catchment areas of Bongo District. We appreciate the concern of the reviewer and have now further edited the relevant paragraphs in both the Introduction (Lines 75-80) and the Discussion (Lines 501-506) to make very clear the dependence of the reported quantity on sample size, but also its feasible extrapolation consistent with the census of a population.

In contrast, I think that sample parasite count will be most useful in an epidemiological context, where the total number of sampled parasites can be contrasted with other metrics to help us better understand how parasites are divided across hosts, space and time. However, for this use, I find it problematic that the metric does not appear to correct for variations in participant number. For instance, in this study, participant numbers especially varied across time for 1-5 year-olds (N=356, 216, 405, and 354 in 2012, 2014, 2015, and 2017 respectively).

The reviewer has made an important point that for the purpose of comparisons across the four surveys or study time points (i.e., 2012, 2014, 2015, and 2017), we should "normalize" the number of individuals considered for the calculation of the "census population size". Given that this quantity is a sum of the estimated MOIvar,, we need to have constant numbers for its values to be compared across the surveys, within age group and the whole population. This is needed not only to get around the issue of the drop in 1-5 year olds surveyed in 2014 but to also stabilize the total number of individuals for the whole sample and for specific age groups. One way to do this is to use the smaller sample size for each age group across time, and to use that value to resample repeatedly for that number of individuals for surveys where we have a larger sample size. This has now been updated included in the manuscript as described in the Materials and Methods (Lines 329-341) and in the Results (Lines 415-430; see updated Figure 4 and Table supplement 7). This correction produces very similar results to those we had presented before (see updated Figure 4 and Table supplement 7).

As stated in our previous response we have used participant number in an interrupted time series where the population was sampled by age to look at age-specific effects of sequential interventions IRS and SMC. As shown in Table supplement 1 of the 16 age-specific samples of the total population, we have sampled very similar proportions of the population by age group across the four surveys. The only exception was the 1-5 year-old age group during the survey in 2014. We are happy to provide additional details to further clarify the lower number (or percentage) of 1-5 year olds (based on the total number of participants per survey) in 2014 (~12%; N = 216) compared to the other surveys conducted 2012, 2015, and 2017 (~18-20%; N = 356, 405, and 354, respectively). Please see Table supplement 1 for the total number of participants surveyed in each of the four surveys (i.e., 2012, 2014, 2015, and 2017).

This sample size variability is accounted for with other metrics like mean MOI.

We agree that mean MOI by age presents a way forward with variable samples to scale up. Please see updated Figure supplement 8.

In sum, while the manuscript opens up an interesting discussion, I'm left with an incomplete understanding of the robustness and interpretability of the new proposed metric.”

We thank you for your opinion. We have further edited the manuscript to make clear our choice of the term and the issue of sample size. We believe the proposed terminology is meaningful as explained above.

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary

The manuscript coins a term "the census population size" which they define from the diversity of malaria parasites observed in the human community. They use it to explore changes in parasite diversity in more than 2000 people in Ghana following different control interventions.

Strengths:

This is a good demonstration of how genetic information can be used to augment routinely recorded epidemiological and entomological data to understand the dynamics of malaria and how it is controlled. The genetic information does add to our understanding, though by how much is currently unclear (in this setting it says the same thing as age stratified parasite prevalence), and its relevance moving forward will depend on the practicalities and cost of the data collection and analysis. Nevertheless, this is a great dataset with good analysis and a good attempt to understand more about what is going on in the parasite population.

Thank you to the reviewer for their supportive assessment of our research.

Weaknesses

None

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations for the authors):

New figure supplement 8 - x-axis says percentage but goes between 0-1, so is a proportion

We thank the reviewer for bringing this to our attention. We have amended the x-axis labels accordingly for Figure supplement 8.

-

-

eLife Assessment

This valuable study highlights how the diversity of the malaria parasite population diminishes following the initiation of effective control interventions but quickly rebounds as control wanes. The data presented is convincing and the work shows how genetic studies could be used to monitor changes in disease transmission.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

In this manuscript, Tiedje and colleagues longitudinally track changes in parasite numbers across four time points as a way of assessing the effect of malaria control interventions in Ghana. Some of the study results have been reported previously, and in this publication, the authors focus on age-stratification of the results. Malaria prevalence was lower in all age groups after IRS. Follow-up with SMC, however, maintained lower parasite prevalence in the targeted age group but not the population as a whole. Additionally, they observe that diversity measures rebound more slowly than prevalence measures. This adds to a growing literature that demonstrates the relevance of asymptomatic reservoirs.

Strengths:

Overall, I found these results clear, convincing, and well-presented. There is growing interest in …

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

In this manuscript, Tiedje and colleagues longitudinally track changes in parasite numbers across four time points as a way of assessing the effect of malaria control interventions in Ghana. Some of the study results have been reported previously, and in this publication, the authors focus on age-stratification of the results. Malaria prevalence was lower in all age groups after IRS. Follow-up with SMC, however, maintained lower parasite prevalence in the targeted age group but not the population as a whole. Additionally, they observe that diversity measures rebound more slowly than prevalence measures. This adds to a growing literature that demonstrates the relevance of asymptomatic reservoirs.

Strengths:

Overall, I found these results clear, convincing, and well-presented. There is growing interest in developing an expanded toolkit for genomic epidemiology in malaria, and detecting changes in transmission intensity is one major application. As the authors summarize, there is no one-size-fits-all approach, and the Bayesian MOIvar estimate developed here has the potential to complement currently used methods, particularly in regions with high diversity/transmission. I find its extension to a calculation of absolute parasite numbers appealing as this could serve as both a conceptually straightforward and biologically meaningful metric.

Weaknesses:

While I understand the conceptual importance of distinguishing among parasite prevalence, mean MOI, and absolute parasite number, I am not fully convinced by this manuscript's implementation of "census population size". The authors reference the population genetic literature, but within the context of that field, "census population size" refers to the total population size (which, if not formally counted, can be extrapolated) as opposed to "effective population" size, which accounts for a multitude of demographic factors. There is often interesting biology to be gleaned from the magnitude of difference between N and Ne. In this manuscript, however, "census population size" is used to describe the number of distinct parasites detected within a sample, not a population. As a result, the counts do not have an immediate population genetic interpretation and cannot be directly compared to Ne. This doesn't negate their usefulness but does complicate the use of a standard population genetic term. In contrast, I think that sample parasite count will be most useful in an epidemiological context, where the total number of sampled parasites can be contrasted with other metrics to help us better understand how parasites are divided across hosts, space and time. However, for this use, I find it problematic that the metric does not appear to correct for variations in participant number. For instance, in this study, participant numbers especially varied across time for 1-5 year-olds (N=356, 216, 405, and 354 in 2012, 2014, 2015, and 2017 respectively). This sample size variability is accounted for with other metrics like mean MOI. In sum, while the manuscript opens up an interesting discussion, I'm left with an incomplete understanding of the robustness and interpretability of the new proposed metric.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

The manuscript coins a term "the census population size" which they define from the diversity of malaria parasites observed in the human community. They use it to explore changes in parasite diversity in more than 2000 people in Ghana following different control interventions.

Strengths:

This is a good demonstration of how genetic information can be used to augment routinely recorded epidemiological and entomological data to understand the dynamics of malaria and how it is controlled. The genetic information does add to our understanding, though by how much is currently unclear (in this setting it says the same thing as age stratified parasite prevalence), and its relevance moving forward will depend on the practicalities and cost of the data collection and analysis. Nevertheless, this is a great …

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

The manuscript coins a term "the census population size" which they define from the diversity of malaria parasites observed in the human community. They use it to explore changes in parasite diversity in more than 2000 people in Ghana following different control interventions.

Strengths:

This is a good demonstration of how genetic information can be used to augment routinely recorded epidemiological and entomological data to understand the dynamics of malaria and how it is controlled. The genetic information does add to our understanding, though by how much is currently unclear (in this setting it says the same thing as age stratified parasite prevalence), and its relevance moving forward will depend on the practicalities and cost of the data collection and analysis. Nevertheless, this is a great dataset with good analysis and a good attempt to understand more about what is going on in the parasite population.

Weaknesses:

None

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Tiedje et al. investigated the transient impact of indoor residual spraying (IRS) followed by seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) on the plasmodium falciparum parasite population in a high transmission setting. The parasite population was characterized by sequencing the highly variable DBL$\alpha$ tag as a proxy for var genes, a method known as varcoding. Varcoding presents a unique opportunity due to the extraordinary diversity observed as well as the extremely low overlap of repertoires between parasite strains. The authors also present a new Bayesian approach to estimating individual multiplicity of infection (MOI) from the measured DBL$\alpha$ repertoire, addressing some of the potential shortcomings of …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Tiedje et al. investigated the transient impact of indoor residual spraying (IRS) followed by seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) on the plasmodium falciparum parasite population in a high transmission setting. The parasite population was characterized by sequencing the highly variable DBL$\alpha$ tag as a proxy for var genes, a method known as varcoding. Varcoding presents a unique opportunity due to the extraordinary diversity observed as well as the extremely low overlap of repertoires between parasite strains. The authors also present a new Bayesian approach to estimating individual multiplicity of infection (MOI) from the measured DBL$\alpha$ repertoire, addressing some of the potential shortcomings of the approach that have been previously discussed. The authors also present a new epidemiological endpoint, the so-called "census population size", to evaluate the impact of interventions. This study provides a nice example of how varcoding technology can be leveraged, as well as the importance of using diverse genetic markers for characterizing populations, especially in the context of high transmission. The data are robust and clearly show the transient impact of IRS in a high transmission setting, however, some aspects of the analysis are confusing.

(1) Approaching MOI estimation with a Bayesian framework is a well-received addition to the varcoding methodology that helps to address the uncertainty associated with not knowing the true repertoire size. It's unfortunate that while the authors clearly explored the ability to estimate the population MOI distribution, they opted to use only MAP estimates. Embracing the Bayesian methodology fully would have been interesting, as the posterior distribution of population MOI could have been better explored.

We thank the reviewer for appreciating the extension of _var_coding we present here. We believe the comment on maximum a posteriori (MAP) refers to the way we obtained population-level MOI from the individual MOI estimates. We would like to note that reliance on MAP was only one of two approaches we described, although we then presented only MAP. Having calculated both, we did not observe major differences between the two, for this data set. Nonetheless, we revised the manuscript to include the result based on the mixture distribution which considers all the individual MOI distributions in the Figure supplement 6.

(2) The "census population size" endpoint has unclear utility. It is defined as the sum of MOI across measured samples, making it sensitive to the total number of samples collected and genotyped. This means that the values are not comparable outside of this study, and are only roughly comparable between strata in the context of prevalence where we understand that approximately the same number of samples were collected. In contrast, mean MOI would be insensitive to differences in sample size, why was this not explored? It's also unclear in what way this is a "census". While the sample size is certainly large, it is nowhere near a complete enumeration of the parasite population in question, as evidenced by the extremely low level of pairwise type sharing in the observed data.

We consider the quantity a census in that it is a total enumeration or count of infections in a given population sample and over a given time period. In this sense, it gives us a tangible notion of the size of the parasite population, in an ecological sense, distinct from the formal effective population size used in population genetics. Given the low overlap between var repertoires of parasites (as observed in monoclonal infections), the population size we have calculated translates to a diversity of strains or repertoires. But our focus here is in a measure of population size itself. The distinction between population size in terms of infection counts and effective population size from population genetics has been made before for pathogens (see for example Bedford et al. for the seasonal influenza virus and for the measles virus (Bedford et al., 2011)), and it is also clear in the ecological literature for non-pathogen populations (Palstra and Fraser, 2012).

We completely agree with the dependence of our quantity on sample size. We used it for comparisons across time of samples of the same depth, to describe the large population size characteristic of high transmission which persists across the IRS intervention. Of course, one would like to be able to use this quantity across studies that differ in sampling depth and the reviewer makes an insightful and useful suggestion. It is true that we can use mean MOI, and indeed there is a simple map between our population size and mean MOI (as we just need to divide or multiply by sample size, respectively) (Table supplement 7). We can go further, as with mean MOI we can presumably extrapolate to the full sample size of the host population, or to the population size of another sample in another location. What is needed for this purpose is a stable mean MOI relative to sample size. We can show that indeed in our study mean MOI is stable in that way, by subsampling to different depths our original sample (Figure supplement 8 in the revised manuscript). We now include in the revision discussion of this point, which allows an extrapolation of the census population size to the whole population of hosts in the local area.

We have also clarified the time denominator: Given the typical duration of infection, we expect our population size to be representative of a per-generation measure_._

(3) The extraordinary diversity of DBL$\alpha$ presents challenges to analyzing the data. The authors explore the variability in repertoire richness and frequency over the course of the study, noting that richness rapidly declined following IRS and later rebounded, while the frequency of rare types increased, and then later declined back to baseline levels. The authors attribute this to fundamental changes in population structure. While there may have been some changes to the population, the observed differences in richness as well as frequency before and after IRS may also be compatible with simply sampling fewer cases, and thus fewer DBL$\alpha$ sequences. The shift back to frequency and richness that is similar to pre-IRS also coincides with a similar total number of samples collected. The authors explore this to some degree with their survival analysis, demonstrating that a substantial number of rare sequences did not persist between timepoints and that rarer sequences had a higher probability of dropping out. This might also be explained by the extreme stochasticity of the highly diverse DBL$\alpha$, especially for rare sequences that are observed only once, rather than any fundamental shifts in the population structure.

We thank the reviewer raising this question which led us to consider whether the change in the number of DBLα types over the course of the study (and intervention) follows from simply sampling fewer P. falciparum cases. We interpreted this question as basically meaning that one can predict the former from the latter in a simple way, and that therefore, tracking the changes in DBLα type diversity would be unnecessary. A simple map would be for example a linear relationship (a given proportion of DBLα types lost given genomes lost), and even more trivially, a linear loss with a slope of one (same proportion). Note, however, that for such expectations, one needs to rely on some knowledge of strain structure and gene composition. In particular, we would need to assume a complete lack of overlap and no gene repeats in a given genome. We have previously shown that immune selection leads to selection for minimum overlap and distinct genes in repertoires at high transmission (see for example (He et al., 2018)) for theoretical and empirical evidence of both patterns). Also, since the size of the gene pool is very large, even random repertoires would lead to limited overlap (even though the empirical overlap is even smaller than that expected at random (Day et al., 2017)). Despite these conservators, we cannot a priori assume a pattern of complete non-overlap and distinct genes, and ignore plausible complexities introduced by the gene frequency distribution.

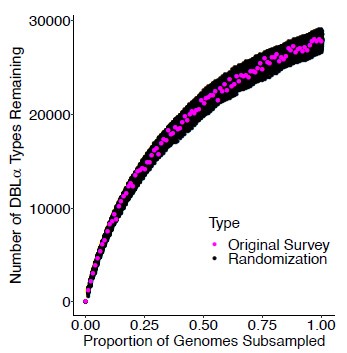

To examine this insightful question, we simulated the loss of a given proportion of genomes from baseline in 2012 and examined the resulting loss of DBLα types. We specifically cumulated the loss of infections in individuals until it reached a given proportion (we can do this on the basis of the estimated individual MOI values). We repeated this procedure 500 times for each proportion, as the random selection of individual infection to be removed, introduces some variation. Figure 2 below shows that the relationship is nonlinear, and that one quantity is not a simple proportion of the other. For example, the loss of half the genomes does not result in the loss of half the DBLα types.

Author response image 1.

Non-linear relationship between the loss of DBLα types and the loss of a given proportion of genomes. The graph shows that the removal of parasite genomes from the population through intervention does not lead to the loss of the same proportion of DBLα types, as the initial removal of genomes involves the loss of rare DBLα types mostly whereas common DBLα types persist until a high proportion of genomes are lost. The survey data (pink dots) used for this subsampling analysis was sampled at the end of wet/high transmission season in Oct 2012 from Bongo District from northern Ghana. We used the Bayesian formulation of the _var_coding method proposed in this work to calculate the multiplicity of infection of each isolate to further obtain the total number of genomes. The randomized surveys (black dots) were obtained based on “curveball algorithm” (Strona et al., 2014) which keep isolate lengths and type frequency distribution.

We also investigated whether the resulting pattern changed significantly if we randomized the composition of the isolates. We performed such randomization with the “curveball algorithm” (Strona et al., 2014). This algorithm randomizes the presence-absence matrix with rows corresponding to the isolates and columns, to the different DBLα types; importantly, it preserves the DBLα type frequency and the length of isolates. We generated 500 randomizations and repeated the simulated loss of genomes as above. The data presented in Figure 2 above show that the pattern is similar to that obtained for the empirical data presented in this study in Ghana. We interpret this to mean that the number of genes is so large, that the reduced overlap relative to random due to immune selection (see (Day et al., 2017)) does not play a key role in this specific pattern.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

In this manuscript, Tiedje and colleagues longitudinally track changes in parasite numbers across four time points as a way of assessing the effect of malaria control interventions in Ghana. Some of the study results have been reported previously, and in this publication, the authors focus on age-stratification of the results. Malaria prevalence was lower in all age groups after IRS. Follow-up with SMC, however, maintained lower parasite prevalence in the targeted age group but not the population as a whole. Additionally, they observe that diversity measures rebounds more slowly than prevalence measures. Overall, I found these results clear, convincing, and well-presented. They add to a growing literature that demonstrates the relevance of asymptomatic reservoirs. There is growing interest in developing an expanded toolkit for genomic epidemiology in malaria, and detecting changes in transmission intensity is one major application. As the authors summarize, there is no one-size-fits-all approach, and the Bayesian MOIvar estimate developed here has the potential to complement currently used methods. I find its extension to a calculation of absolute parasite numbers appealing as this could serve as both a conceptually straightforward and biologically meaningful metric. However, I am not fully convinced the current implementation will be applied meaningfully across additional studies.

(1) I find the term "census population size" problematic as the groups being analyzed (hosts grouped by age at a single time point) do not delineate distinct parasite populations. Separate parasite lineages are not moving through time within these host bins. Rather, there is a single parasite population that is stochastically divided across hosts at each time point. I find this distinction important for interpreting the results and remaining mindful that the 2,000 samples at each time point comprise a subsample of the true population. Instead of "census population size", I suggest simplifying it to "census count" or "parasite lineage count". It would be fascinating to use the obtained results to model absolute parasite numbers at the whole population level (taking into account, for instance, the age structure of the population), and I do hope this group takes that on at some point even if it remains outside the scope of this paper. Such work could enable calculations of absolute---rather than relative---fitness and help us further understand parasite distributions across hosts.

Lineages moving exclusively through a given type of host or “patch” are not a necessary requirement for enumerating the size of the total infections in such subset. It is true that what we have is a single parasite population, but we are enumerating for the season the respective size in host classes (children and adults). This is akin to enumerating subsets of a population in ecological settings where one has multiple habitat patches, with individuals able to move across patches.

Remaining mindful that the count is relative to sample size is an important point. Please see our response to comment (2) of reviewer 1, also for the choice of terminology. We prefer not to adopt “census count” as a census in our mind is a count, and we are not clear on the concept of lineage for these highly recombinant parasites. Also, census population size has been adopted already in the literature for both pathogens and non-pathogens, to make a distinction with the notion of effective population size in population genetics (see our response to reviewer 1) and is consistent with our usage as outlined in the introduction.

Thank you for the comment on an absolute number which would extrapolate to the whole host population. Please see again our response to comment (2) of reviewer 1, on how we can use mean MOI for this purpose once the sampling is sufficient for this quantity to become constant/stable with sampling effort.

(2) I'm uncertain how to contextualize the diversity results without taking into account the total number of samples analyzed in each group. Because of this, I would like a further explanation as to why the authors consider absolute parasite count more relevant than the combined MOI distribution itself (which would have sample count as a denominator). It seems to me that the "per host" component is needed to compare across age groups and time points---let alone different studies.

Again, thank you for the insightful comment. We provide this number as a separate quantity and not a distribution, although it is clearly related to the mean MOI of such distribution. It gives a tangible sense for the actual infection count (different from prevalence) from the perspective of the parasite population in the ecological sense. The “per host” notion which enables an extrapolation to any host population size for the purpose of a complete count, or for comparison with another study site, has been discussed in the above responses for reviewer 1 and now in the revision of the discussion.

(3) Thinking about the applicability of this approach to other studies, I would be interested in a larger treatment of how overlapping DBLα repertoires would impact MOIvar estimates. Is there a definable upper bound above which the method is unreliable? Alternatively, can repertoire overlap be incorporated into the MOI estimator?

This is a very good point and one we now discuss further in our revision. There is no predefined upper bound one can present a priori. Intuitively, the approach to estimate MOI would appear to breakdown as overlap moves away from extremely low values, and therefore for locations with low transmission intensity. Interestingly, we have observed that this is not the case in our paper by Labbe et al. (Labbé et al., 2023) where we used model simulations in a gradient of three transmission intensities, from high to low values. The original _var_coding method performed well across the gradient. This robustness may arise from a nonlinear and fast transition from low to high overlap that is accompanied by MOI changing rapidly from primarily multiclonal (MOI > 1) to monoclonal (MOI = 1). This matter clearly needs to be investigated further, including ways to extend the estimation to explicitly include the distribution of overlap.

Smaller comments:

- Figure 1 provides confidence intervals for the prevalence estimates, but these aren't carried through on the other plots (and Figure 5 has lost CIs for both metrics). The relationship between prevalence and diversity is one of the interesting points in this paper, and it would be helpful to have CIs for both metrics when they are directly compared.

Based on the reviewer’s advice we have revised both Figure 4 and Figure 5, to include the missing uncertainty intervals. The specific approach for each quantity is described in the corresponding caption.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Summary:

The manuscript coins a term "the census population size" which they define from the diversity of malaria parasites observed in the human community. They use it to explore changes in parasite diversity in more than 2000 people in Ghana following different control interventions.

Strengths:

This is a good demonstration of how genetic information can be used to augment routinely recorded epidemiological and entomological data to understand the dynamics of malaria and how it is controlled. The genetic information does add to our understanding, though by how much is currently unclear (in this setting it says the same thing as age-stratified parasite prevalence), and its relevance moving forward will depend on the practicalities and cost of the data collection and analysis. Nevertheless, this is a great dataset with good analysis and a good attempt to understand more about what is going on in the parasite population.

Census population size is complementary to parasite prevalence where the former gives a measure of the “parasite population size”, and the latter describes the “proportion of infected hosts”. The reason we see similar trends for the “genetic information” (i.e., census population size) and “age-specific parasite prevalence” is because we identify all samples for _var_coding based on the microscopy (i.e., all microscopy positive P. falciparum isolates). But what is more relevant here is the relative percentage change in parasite prevalence and census population size following the IRS intervention. To make this point clearer in the revised manuscript we have updated Figure 4 and included additional panels plotting this percentage change from the 2012 baseline, for both census population size and prevalence (Figure 4EF). Overall, we see a greater percentage change in 2014 (and 2015), relative to the 2012 baseline, for census parasite population size vs. parasite prevalence (Figure 4EF) as a consequence of the significant changes in distributions of MOI following the IRS intervention (Figure 3). As discussed in the Results following the deployment of IRS in 2014 census population size decreased by 72.5% relative to the 2012 baseline survey (pre-IRS) whereas parasite prevalence only decreased by 54.5%.

With respect to the reviewer’s comment on “practicalities and cost”, _var_coding has been used to successfully amplify P. falciparum DNA collected as DBS that have been stored for more than 5-years from both clinical and lower density asymptomatic infection, without the additional step and added cost of sWGA ($8 to $32 USD per isolates, for costing estimates see (LaVerriere et al., 2022; Tessema et al., 2020)), which is currently required by other molecular surveillance methods (Jacob et al., 2021; LaVerriere et al., 2022; Oyola et al., 2016). _Var_coding involves a single PCR per isolate using degenerate primers, where a large number of isolates can be multiplexed into a single pool for amplicon sequencing. Thus, the overall costs for incorporating molecular surveillance with _var_coding are mainly driven by the number of PCRs/clean-ups, the number samples indexed per sequencing run, and the NGS technology used (discussed in more detail in our publication Ghansah et al. (Ghansah et al., 2023)). Previous work has shown that _var_coding can be use both locally and globally for molecular surveillance, without the need to be customized or updated, thus it can be fairly easily deployed in malaria endemic regions (Chen et al., 2011; Day et al., 2017; Rougeron et al., 2017; Ruybal-Pesántez et al., 2022, 2021; Tonkin-Hill et al., 2021).

Weaknesses:

Overall the manuscript is well-written and generally comprehensively explained. Some terms could be clarified to help the reader and I had some issues with a section of the methods and some of the more definitive statements given the evidence supporting them.

Thank you for the overall positive assessment. On addressing the “issues with a section of the methods” and “some of the more definitive statements given the evidence supporting them”, it is impossible to do so however, without an explicit indication of which methods and statements the reviewer is referring to. Hopefully, the answers to the detailed comments and questions of reviewers 1 and 2 address any methodological concerns (i.e., in the Materials and Methods and Results). To the issue of “definitive statements”, etc. we are unable to respond without further information.

Recommendations For The Authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations For The Authors):

Line 273: there is a reference to a figure which supports the empirical distribution of repertoire given MOI = 1, but the figure does not appear to exist.

We now included the correct figure for the repertoire size distribution as Figure supplement 3 (previously published in Labbé et al (Labbé et al., 2023)). This figure was accidently forgotten when the manuscript was submitted for review, we thank the reviewer for bringing this to our attention.

Line 299: while this likely makes little difference, an insignificant result from a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test doesn't tell you if the distributions are the same, it only means there is not enough evidence to determine they are different (i.e. fail to reject the null). Also, what does the "mean MOI difference" column in supplementary table 3 mean?

The mean MOI difference is the difference in the mean value between the pairwise comparison of the true population-level MOI distribution, that of the population-level MOI estimates from either pooling the maximum a posteriori (MAP) estimates per individual host or the mixture distribution, or that of the population-level MOI estimates from different prior choices. This is now clarified as requested in the Table supplements 3 - 6.

Figure 4: how are the confidence intervals for the estimated number of var repertoires calculated? Also should include horizontal error bars for prevalence measures.

The confidence intervals were calculated based on a bootstrap approach. We re-sampled 10,000 replicates from the original population-level MOI distribution with replacement. Each resampled replicate is the same size as the original sample. We then derive the 95% CI based on the distribution of the mean MOI of those resampled replicates. This is now clarified as requested in the Figure 4 caption (as well as Table supplement 7 footnotes). In addition, we have also updated Figure 4AB and have included the 95% CI for all measures for clarity.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations For The Authors):

- I would like to see a plot like Supplemental Figure 8 for the upsA DBLα repertoire size.

The upsA repertoire size for each survey and by age group has now been provided as requested in Figure supplement 5AB.

- Supplemental Table 2 is cut off in the pdf.

We have now resolved this issue so that the Table supplement 2 is no longer cut off.

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations For The Authors):

The manuscript terms the phrase "census population size". To me, the census is all about the number of individuals, not necessarily their diversity. I appreciate that there is no simple term for this, and I imagine the authors have considered many alternatives, but could it be clearer to say the "genetic census population size"? For example, I found the short title not particularly descriptive "Impact of IRS and SMC on census population size", which certainly didn't make me think of parasite diversity.

Please see our response to comment (2) of reviewer 1. We prefer not to add “genetic” to the phrase as the distinction from effective population size from population genetics is important, and the quantity we are after is an ecological one.

The authors do not currently say much about the potential biases in the genetic data and how this might influence results. It seems likely that because (i) patients with sub-microscopic parasitaemia were not sampled and (ii) because a moderate number of (likely low density) samples failed to generate genetic data, that the observed MOI is an overestimate. I'd be interested to hear the authors' thoughts about how this could be overcome or taken into account in the future.

We thank the reviewer for this this comment and agree that this is an interesting area for further consideration. However, based on research from the Day Lab that is currently under review (Tan et al. 2024, under review), the estimated MOI using the Bayesian approach is likely not an “overestimate” but rather an “underestimate”. In this research by Tan et al. (2024) isolate MOI was estimated and compared using different initial whole blood volumes (e.g., 1, 10, 50, 100 uL) for the gDNA extraction. Using _var_coding and comparing these different volumes it was found that MOI was significantly “underestimated” when small blood volumes were used for the gDNA extraction, i.e., there was a ~3-fold increase in median MOI between 1μL and 100μL blood. Ultimately these findings will allow us to make computational corrections so that more accurate estimates of MOI can be obtained from the DBS in the future.

The authors do not make much of LLIN use and for me, this can explain some of the trends. The first survey was conducted soon after a mass distribution whereas the last was done at least a year after (when fewer people would have been using the nets which are older and less effective). We have also seen a rise in pyrethroid resistance in the mosquito populations of the area which could further diminish the LLIN activity. This difference in LLIN efficacy between the first and last survey could explain similar prevalence, yet lower diversity (in Figures 4B/5). However, it also might mean that statements such as Line 478 "This is indicative of a loss of immunity during IRS which may relate to the observed loss of var richness, especially the many rare types" need to be tapered as the higher prevalence observed in this age group could be caused by lower LLIN efficacy at the time of the last survey, not loss of immunity (though both could be true).

We thank the reviewer for this question and agree that (i) LLIN usage and (ii) pyrethroid resistance are important factors to consider.

(i) Over the course of this study self-reported LLIN usage the previous night remained high across all age groups in each of the surveys (≥ 83.5%), in fact more participants reported sleeping under an LLIN in 2017 (96.8%) following the discontinuation of IRS compared to the 2012 baseline survey (89.1%). This increase in LLIN usage in 2017 is likely a result of several factors including a rebound in the local vector population making LLINs necessary again, increased community education and/or awareness on the importance of using LLINs, among others. Information on the LLINs (i.e., PermaNet 2.0, Olyset, or DawaPlus 2.0) distributed and participant reported usage the previous night has now been included in the Materials and Methods as requested by the reviewer.

(ii) As to the reviewer’s question on increased in pyrethroid resistance in Ghana over the study period, research undertaken by our entomology collaborators (Noguchi Memorial Insftute for Medical Research: Profs. S. Dadzie and M. Appawu; and Navrongo Health Research Centre: Dr. V. Asoala) has shown that pyrethroid resistance is a major problem across the country, including the Upper East Region. Preliminary studies from Bongo District (2013 - 2015), were undertaken to monitor for mutations in the voltage gated sodium channel gene that have been associated with knockdown resistance to pyrethroids and DDT in West Africa (kdr-w). Through this analysis the homozygote resistance kdr-w allele (RR) was found in 90% of An. gambiae s.s. samples tested from Bongo, providing evidence of high pyrethroid resistance in Bongo District dating back to 2013, i.e., prior to the IRS intervention (S. Dadzie, M. Appawu, personal communication). Although we do not have data in Bongo District on kdr-w from 2017 (i.e., post-IRS), we can hypothesize that pyrethroid resistance likely did not decline in the area, given the widespread deployment and use of LLINs.

Thus, given this information that (i) self-reported LLIN usage remained high in all surveys (≥ 83.5%), and that (ii) there was evidence of high pyrethroid resistance in 2013 (i.e., kdr-w (RR) _~_90%), the rebound in prevalence observed for the older age groups (i.e., adolescents and adults) in 2017 is therefore best explained by a loss of immunity.

I must confess I got a little lost with some of the Bayesian model section methods and the figure supplements. Line 272 reads "The measurement error is simply the repertoire size distribution, that is, the distribution of the number of non-upsA DBLα types sequenced given MOI = 1, which is empirically available (Figure supplement 3)." This does not appear correct as this figure is measuring kl divergence. If this is not a mistake in graph ordering please consider explaining the rationale for why this graph is being used to justify your point.

We now included the correct figure for the repertoire size distribution as Figure supplement 3 (previously published in Labbé et al (Labbé et al., 2023)). This figure was accidently forgotten when the manuscript was submitted for review, we thank the reviewer for bringing our attention to this matter. We hope that the inclusion of this Figure as well as a more detailed description of the Bayesian approach helps to makes this section in the Materials and Methods clearer for the reader.

I was somewhat surprised that the choice of prior for estimating the MOI distribution at the population level did not make much difference. To me, the negative binomial distribution makes much more sense. I was left wondering, as you are only measuring MOI in positive individuals, whether you used zero truncated Poisson and zero truncated negative binomial distributions, and if not, whether this was a cause of a lack of difference between uniform and other priors.

Thank you for the relevant question. We have indeed considered different priors and the robustness of our estimates to this choice and have now better described this in the text. We focused on individuals who had a confirmed microscopic asymptomatic P. falciparum infection for our MOI estimation, as median P. falciparum densities were overall low in this population during each survey (i.e., median ≤ 520 parasites/µL, see Table supplement 1). Thus, we used either a uniform prior excluding zero or a zero truncated negative binomial distribution when exploring the impact of priors on the final population-level MOI distribution. A uniform prior and a zero-truncated negative binomial distribution with parameters within the range typical of high-transmission endemic regions (higher mean MOI with tails around higher MOI values) produce similar MOI estimates at both the individual and population level. However, when setting the parameter range of the zero-truncated negative binomial to be of those in low transmission endemic regions where the empirical MOI distribution centers around mono-clonal infections with the majority of MOI = 1 or 2 (mean MOI » 1.5, no tail around higher MOI values), the final population-level MOI distribution does deviate more from that assuming the aforementioned prior and parameter choices. The final individual- and population-level MOI estimates are not sensitive to the specifics of the prior MOI distribution as long as this distribution captures the tail around higher MOI values with above-zero probability.

The high MOI in children <5yrs in 2017 (immediately after SMC) is very interesting. Any thoughts on how/why?

This result indicates that although the prevalence of asymptomatic P. falciparum infections remained significantly lower for the younger children targeted by SMC in 2017 compared 2012, they still carried multiclonal infections, as the reviewer has pointed out (Figure 3B). Importantly this upward shift in the MOI distributions (and median MOI) was observed in all age groups in 2017, not just the younger children, and provides evidence that transmission intensity in Bongo has rebounded in 2017, 32-months a er the discontinuation of IRS. This increase in MOI for younger children at first glance may seem to be surprising, but instead likely shows the limitations of SMC to clear and/or supress the establishment of newly acquired infections, particularly at the end of the transmission season following the final cycle of SMC (i.e., end of September 2017 in Bongo District; NMEP/GHS, personal communication) when the posttreatment prophylactic effects of SMC would have waned (Chotsiri et al., 2022).

Line 521 in the penultimate paragraph says "we have analysed only low density...." should this not be "moderate" density, as low density infections might not be detected? The density range itself is not reported in the manuscript so could be added.

In Table supplement 1 we have provided the median, including the inter-quartile range, across each survey by age group. For the revision we have now provided the density min-max range, as requested by the reviewer. Finally, we have revised the statement in the discussion so that it now reads “….we have analysed low- to moderate-density, chronic asymptomatic infections (see Table supplement 1)……”.

Data availability - From the text the full breakdown of the epidemiological survey does not appear to be available, just a summary of defined age bounds in the SI. Provision of these data (with associated covariates such as parasite density and host characteristics linked to genetic samples) would facilitate more in-depth secondary analyses.

To address this question, we have updated the “Data availability statement” section with the following statement: “All data associated with this study are available in the main text, the Supporting Information, or upon reasonable request for research purposes to the corresponding author, Prof. Karen Day (karen.day@unimelb.edu.au).”

REFERENCES

Bedford T, Cobey S, Pascual M. 2011. Strength and tempo of selection revealed in viral gene genealogies. BMC Evol Biol 11. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-220

Chen DS, Barry AE, Leliwa-Sytek A, Smith T-AA, Peterson I, Brown SM, Migot-Nabias F, Deloron P, Kortok MM, Marsh K, Daily JP, Ndiaye D, Sarr O, Mboup S, Day KP. 2011. A molecular epidemiological study of var gene diversity to characterize the reservoir of Plasmodium falciparum in humans in Africa. PLoS One 6:e16629. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016629

Chotsiri P, White NJ, Tarning J. 2022. Pharmacokinetic considerations in seasonal malaria chemoprevention. Trends Parasitol. doi:10.1016/j.pt.2022.05.003

Day KP, Artzy-Randrup Y, Tiedje KE, Rougeron V, Chen DS, Rask TS, Rorick MM, Migot-Nabias F, Deloron P, Luty AJF, Pascual M. 2017. Evidence of Strain Structure in Plasmodium falciparum Var Gene Repertoires in Children from Gabon, West Africa. PNAS 114:E4103–E4111. doi:10.1073/pnas.1613018114

Ghansah A, Tiedje KE, Argyropoulos DC, Onwona CO, Deed SL, Labbé F, Oduro AR, Koram KA, Pascual M, Day KP. 2023. Comparison of molecular surveillance methods to assess changes in the population genetics of Plasmodium falciparum in high transmission. Fron9ers in Parasitology 2:1067966. doi: 10.3389/fpara.2023.1067966

He Q, Pilosof S, Tiedje KE, Ruybal-Pesántez S, Artzy-Randrup Y, Baskerville EB, Day KP, Pascual M. 2018. Networks of genetic similarity reveal non-neutral processes shape strain structure in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Commun 9:1817. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04219-3

Jacob CG, Thuy-nhien N, Mayxay M, Maude RJ, Quang HH, Hongvanthong B, Park N, Goodwin S, Ringwald P, Chindavongsa K, Newton P, Ashley E. 2021. Genetic surveillance in the Greater Mekong subregion and South Asia to support malaria control and elimination. Elife 10:1–22.

Labbé F, He Q, Zhan Q, Tiedje KE, Argyropoulos DC, Tan MH, Ghansah A, Day KP, Pascual M. 2023. Neutral vs . non-neutral genetic footprints of Plasmodium falciparum multiclonal infections. PLoS Comput Biol 19:e1010816. doi:doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.27.497801

LaVerriere E, Schwabl P, Carrasquilla M, Taylor AR, Johnson ZM, Shieh M, Panchal R, Straub TJ, Kuzma R, Watson S, Buckee CO, Andrade CM, Portugal S, Crompton PD, Traore B, Rayner JC, Corredor V, James K, Cox H, Early AM, MacInnis BL, Neafsey DE. 2022. Design and implementation of multiplexed amplicon sequencing panels to serve genomic epidemiology of infectious disease: A malaria case study. Mol Ecol Resour 2285–2303. doi:10.1111/1755-0998.13622

Oyola SO, Ariani C V., Hamilton WL, Kekre M, Amenga-Etego LN, Ghansah A, Rutledge GG, Redmond S, Manske M, Jyothi D, Jacob CG, Ogo TD, Rockeg K, Newbold CI, Berriman M, Kwiatkowski DP. 2016. Whole genome sequencing of Plasmodium falciparum from dried blood spots using selecFve whole genome amplification. Malar J 15:1–12. doi:10.1186/s12936-016-1641-7

Palstra FP, Fraser DJ. 2012. Effective/census population size ratio estimation: A compendium and appraisal. Ecol Evol 2:2357–2365. doi:10.1002/ece3.329

Rougeron V, Tiedje KE, Chen DS, Rask TS, Gamboa D, Maestre A, Musset L, Legrand E, Noya O, Yalcindag E, Renaud F, Prugnolle F, Day KP. 2017. Evolutionary structure of Plasmodium falciparum major variant surface antigen genes in South America : Implications for epidemic transmission and surveillance. Ecol Evol 7:9376–9390. doi:10.1002/ece3.3425

Ruybal-Pesántez S, Sáenz FE, Deed S, Johnson EK, Larremore DB, Vera-Arias CA, Tiedje KE, Day KP. 2021. Clinical malaria incidence following an outbreak in Ecuador was predominantly associated with Plasmodium falciparum with recombinant variant antigen gene repertoires. medRxiv.

Ruybal-Pesántez S, Tiedje KE, Pilosof S, Tonkin-Hill G, He Q, Rask TS, Amenga-Etego L, Oduro AR, Koram KA, Pascual M, Day KP. 2022. Age-specific patterns of DBLa var diversity can explain why residents of high malaria transmission areas remain susceptible to Plasmodium falciparum blood stage infection throughout life. Int J Parasitol 20:721–731.

Strona G, Nappo D, Boccacci F, Fagorini S, San-Miguel-Ayanz J. 2014. A fast and unbiased procedure to randomize ecological binary matrices with fixed row and column totals. Nat Commun 5. doi:10.1038/ncomms5114

Tessema SK, Hathaway NJ, Teyssier NB, Murphy M, Chen A, Aydemir O, Duarte EM, Simone W, Colborn J, Saute F, Crawford E, Aide P, Bailey JA, Greenhouse B. 2020. Sensitive, highly multiplexed sequencing of microhaplotypes from the Plasmodium falciparum heterozygome. Journal of Infec9ous Diseases 225:1227–1237.

Tonkin-Hill G, Ruybal-Pesántez S, Tiedje KE, Rougeron V, Duffy MF, Zakeri S, Pumpaibool T, Harnyuganakorn P, Branch OH, Ruiz-Mesıa L, Rask TS, Prugnolle F, Papenfuss AT, Chan Y, Day KP. 2021. Evolutionary analyses of the major variant surface antigen-encoding genes reveal population structure of Plasmodium falciparum within and between continents. PLoS Genet 7:e1009269. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1009269

-

-

Author Response

We are delighted that eLife has assessed our study as a valuable contribution as well as appreciating the importance of working on asymptomatic reservoirs of P. falciparum in high transmission where not just children, but adolescents and adults harbor multiclonal infections. The constructive public reviews will serve to improve our manuscript.

Detailed responses to referees’ comments and a revised manuscript are forthcoming. Here we make a provisional response to three key areas addressed by the referees:

(1) census population size

Referee 1 raises important questions although we respectfully disagree on the terminology we have adopted (of “census”) and on the unclear utility of the proposed quantity.

We consider the quantity a census in that it is a total enumeration or count of the infections in a given population …

Author Response

We are delighted that eLife has assessed our study as a valuable contribution as well as appreciating the importance of working on asymptomatic reservoirs of P. falciparum in high transmission where not just children, but adolescents and adults harbor multiclonal infections. The constructive public reviews will serve to improve our manuscript.

Detailed responses to referees’ comments and a revised manuscript are forthcoming. Here we make a provisional response to three key areas addressed by the referees:

(1) census population size

Referee 1 raises important questions although we respectfully disagree on the terminology we have adopted (of “census”) and on the unclear utility of the proposed quantity.

We consider the quantity a census in that it is a total enumeration or count of the infections in a given population sample and over a given time period. In this sense, it gives us a tangible notion of the size of the parasite population, in an ecological sense, distinct from the formal effective population size used in population genetics. Given the low overlap between var repertoires of parasites (as observed in monoclonal infections), the population size we have calculated translates to a diversity of strains or repertoires. But our focus here is in a measure of population size itself. The distinction between population size in terms of infection counts and effective population size from population genetics has been made before for pathogens (see for example Bedford et al. 2011 for the seasonal influenza virus and for the measles virus) and is a clear one in the ecological literature for non-pathogen populations (Palstra et al. 2012).

Both referees 1 and 2 point out that census population size will be sensitive to sample size. We completely agree with the dependence of our quantity on sample size. We used it for comparisons across time of samples of the same depth, to describe the large population size characteristic of high transmission, and persistent across the IRS intervention. Of course, one would like to be able to use this notion across studies that differ in sampling depth.

Here, referee 1 makes an insightful and useful suggestion. It is true that we can use mean MOI, and indeed there is a simple map between our population size and mean MOI (as we just need to divide or multiply by sample size). We can do even more, as with mean MOI we can presumably extrapolate to the full sample size of the host population, or the population size of another sample in another location. What is needed for this purpose is a stable mean MOI relative to sample size. We can show that indeed in our study mean MOI is stable in that way, by subsampling to different depths of our original sample. We will include in the revision discussion of this point and result, which allows an extrapolation of the census population size to the whole population of hosts in the local area. We’ll also clarify the time denominator, as given the typical duration of infections, we expect our population size to be representative of a per-generation measure.

Referee 2 suggests we adopt the term “census count” but as a census in our mind is a count we prefer to use “census”.

Referee 3 considers the genetic data tracking parasite MOI and census changes gives the same result as prevalence which tracks infected hosts. Respectfully, we disagree and will provide an expanded response.

(2) the importance of lineages (in response to referee 2)

We do not think that lineages moving exclusively through a given type of host or “patch” is a requirement for enumerating the size of the total infections in such a subset. It is true that what we have is a single parasite population, but we are enumerating for the season the respective size in host classes (children and adults). This is akin to enumerating subsets of a population in ecological settings.

We are also not clear on the concept of lineage for these highly recombinant parasites as we struggle to find highly related repertoires. In fact, we see the use of the var fingerprinting methodology as a means to capture changes in strain or var repertoires dynamics as a result of changing transmission conditions.

(3) var methodology

Comments and queries were made by all three referees about aspects of var methodology, including the Bayesian approach. These will be addressed in our full response.

Here we respond to a very good point made by referee 2: “Thinking about the applicability of this approach to other studies, I would be interested in a larger treatment of how overlapping DBLa repertoires would impact MOIvar estimates. Is there a definable upper bound above which the method is unreliable? Alternatively, can repertoire overlap be incorporated into the MOI estimator?”

There is no predefined threshold one can present a priori. Intuitively, the approach to estimate MOI would appear to breakdown as overlap moves away from extremely low, and therefore, for locations with lower transmission intensity. Interestingly, we have observed that this is not the case in our paper by Labbé et al. 2023 where we used model simulations in a gradient of three transmission intensities, from high to low. The original varcoding method performed well across the gradient. This may arise from a nonlinear and fast transition from low overlap to high overlap that is accompanied by the MOI transitioning quickly from primarily multiclonal (MOI > 1) to monoclonal (MOI = 1). This issue needs to be investigated further, including ways to extend the estimation to explicitly include the distribution of DBL repertoire overlap.

References: Bedford T, Cobey S, Pascual, M. 2011. Strength and tempo of selection revealed in viral gene genealogies. BMC Evol Biol 11, 220. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-11-220

Labbé F, He Q, Zhan Q, Tiedje KE, Argyropoulos DC, Tan MH, Ghansah A, Day KP, Pascual M. 2023. Neutral vs . non-neutral genetic footprints of Plasmodium falciparum multiclonal infections. PLoS Comput Biol 19 :e1010816. doi:doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.27.49780

Palstra FP, Fraser DJ. 2012. Effective/census population size ratio estimation: a compendium and appraisal. Ecol Evol. Sep;2(9):2357-65. doi:10.1002/ece3.329.

-

eLife assessment

This valuable study highlights how the diversity of the malaria parasite population diminishes following the initiation of effective control interventions but quickly rebounds as control wanes. The data presented is solid and the work shows how genetic studies could be used to monitor changes in disease transmission.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Tiedje et al. investigated the transient impact of indoor residual spraying (IRS) followed by seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) on the plasmodium falciparum parasite population in a high transmission setting. The parasite population was characterized by sequencing the highly variable DBL$\alpha$ tag as a proxy for var genes, a method known as varcoding. Varcoding presents a unique opportunity due to the extraordinary diversity observed as well as the extremely low overlap of repertoires between parasite strains. The authors also present a new Bayesian approach to estimating individual multiplicity of infection (MOI) from the measured DBL$\alpha$ repertoire, addressing some of the potential shortcomings of the approach that have been previously discussed. The authors also present a new epidemiological …

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Tiedje et al. investigated the transient impact of indoor residual spraying (IRS) followed by seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) on the plasmodium falciparum parasite population in a high transmission setting. The parasite population was characterized by sequencing the highly variable DBL$\alpha$ tag as a proxy for var genes, a method known as varcoding. Varcoding presents a unique opportunity due to the extraordinary diversity observed as well as the extremely low overlap of repertoires between parasite strains. The authors also present a new Bayesian approach to estimating individual multiplicity of infection (MOI) from the measured DBL$\alpha$ repertoire, addressing some of the potential shortcomings of the approach that have been previously discussed. The authors also present a new epidemiological endpoint, the so-called "census population size", to evaluate the impact of interventions.

This study provides a nice example of how varcoding technology can be leveraged, as well as the importance of using diverse genetic markers for characterizing populations, especially in the context of high transmission. The data are robust and clearly show the transient impact of IRS in a high transmission setting, however, some aspects of the analysis are confusing.

Approaching MOI estimation with a Bayesian framework is a well-received addition to the varcoding methodology that helps to address the uncertainty associated with not knowing the true repertoire size. It's unfortunate that while the authors clearly explored the ability to estimate the population MOI distribution, they opted to use only MAP estimates. Embracing the Bayesian methodology fully would have been interesting, as the posterior distribution of population MOI could have been better explored.

The "census population size" endpoint has unclear utility. It is defined as the sum of MOI across measured samples, making it sensitive to the total number of samples collected and genotyped. This means that the values are not comparable outside of this study, and are only roughly comparable between strata in the context of prevalence where we understand that approximately the same number of samples were collected. In contrast, mean MOI would be insensitive to differences in sample size, why was this not explored? It's also unclear in what way this is a "census". While the sample size is certainly large, it is nowhere near a complete enumeration of the parasite population in question, as evidenced by the extremely low level of pairwise type sharing in the observed data.

The extraordinary diversity of DBL$\alpha$ presents challenges to analyzing the data. The authors explore the variability in repertoire richness and frequency over the course of the study, noting that richness rapidly declined following IRS and later rebounded, while the frequency of rare types increased, and then later declined back to baseline levels. The authors attribute this to fundamental changes in population structure. While there may have been some changes to the population, the observed differences in richness as well as frequency before and after IRS may also be compatible with simply sampling fewer cases, and thus fewer DBL$\alpha$ sequences. The shift back to frequency and richness that is similar to pre-IRS also coincides with a similar total number of samples collected. The authors explore this to some degree with their survival analysis, demonstrating that a substantial number of rare sequences did not persist between timepoints and that rarer sequences had a higher probability of dropping out. This might also be explained by the extreme stochasticity of the highly diverse DBL$\alpha$, especially for rare sequences that are observed only once, rather than any fundamental shifts in the population structure.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

In this manuscript, Tiedje and colleagues longitudinally track changes in parasite numbers across four time points as a way of assessing the effect of malaria control interventions in Ghana. Some of the study results have been reported previously, and in this publication, the authors focus on age-stratification of the results. Malaria prevalence was lower in all age groups after IRS. Follow-up with SMC, however, maintained lower parasite prevalence in the targeted age group but not the population as a whole. Additionally, they observe that diversity measures rebounds more slowly than prevalence measures. Overall, I found these results clear, convincing, and well-presented. They add to a growing literature that demonstrates the relevance of asymptomatic reservoirs.

There is growing interest in developing an …

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

In this manuscript, Tiedje and colleagues longitudinally track changes in parasite numbers across four time points as a way of assessing the effect of malaria control interventions in Ghana. Some of the study results have been reported previously, and in this publication, the authors focus on age-stratification of the results. Malaria prevalence was lower in all age groups after IRS. Follow-up with SMC, however, maintained lower parasite prevalence in the targeted age group but not the population as a whole. Additionally, they observe that diversity measures rebounds more slowly than prevalence measures. Overall, I found these results clear, convincing, and well-presented. They add to a growing literature that demonstrates the relevance of asymptomatic reservoirs.

There is growing interest in developing an expanded toolkit for genomic epidemiology in malaria, and detecting changes in transmission intensity is one major application. As the authors summarize, there is no one-size-fits-all approach, and the Bayesian MOIvar estimate developed here has the potential to complement currently used methods. I find its extension to a calculation of absolute parasite numbers appealing as this could serve as both a conceptually straightforward and biologically meaningful metric. However, I am not fully convinced the current implementation will be applied meaningfully across additional studies.

1. I find the term "census population size" problematic as the groups being analyzed (hosts grouped by age at a single time point) do not delineate distinct parasite populations. Separate parasite lineages are not moving through time within these host bins. Rather, there is a single parasite population that is stochastically divided across hosts at each time point. I find this distinction important for interpreting the results and remaining mindful that the 2,000 samples at each time point comprise a subsample of the true population. Instead of "census population size", I suggest simplifying it to "census count" or "parasite lineage count".

It would be fascinating to use the obtained results to model absolute parasite numbers at the whole population level (taking into account, for instance, the age structure of the population), and I do hope this group takes that on at some point even if it remains outside the scope of this paper. Such work could enable calculations of absolute---rather than relative---fitness and help us further understand parasite distributions across hosts.