Hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons modulate sevoflurane anesthesia and the post-anesthesia stress responses

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

eLife assessment

This study presents useful findings for how sevoflurane anesthesia modulates the activity of corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and how manipulation of such PVHCRH neurons influences anesthesia and post-anesthesia responses. The technical approaches are solid and the data presented is largely clear. Whether PVHCRH neurons are critical for the mechanisms of sevoflurane anesthesia is a direction for the future.

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

General anesthesia (GA) is an indispensable procedure necessary for safely and compassionately administering a significant number of surgical procedures and invasive diagnostic tests. However, the undesired stress response associated with GA causes delayed recovery and even increased morbidity in the clinic. Here, a core hypothalamic ensemble, corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVH CRH neurons), is discovered to play a role in regulating sevoflurane GA. Chemogenetic activation of these neurons delay the induction of and accelerated emergence from sevoflurane GA, whereas chemogenetic inhibition of PVH CRH neurons accelerates induction and delays awakening. Moreover, optogenetic stimulation of PVH CRH neurons induce rapid cortical activation during both the steady and deep sevoflurane GA state with burst-suppression oscillations. Interestingly, chemogenetic inhibition of PVH CRH neurons relieve the sevoflurane GA-elicited stress response (e.g., excessive self-grooming and elevated corticosterone level). These findings identify PVH CRH neurons modulate states of anesthesia in sevoflurane GA, being a part of anesthesia regulatory network of sevoflurane.

Article activity feed

-

-

-

-

eLife assessment

This study presents useful findings for how sevoflurane anesthesia modulates the activity of corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus and how manipulation of such PVHCRH neurons influences anesthesia and post-anesthesia responses. The technical approaches are solid and the data presented is largely clear. Whether PVHCRH neurons are critical for the mechanisms of sevoflurane anesthesia is a direction for the future.

-

Joint Public Review:

This study describes a group of CRH-releasing neurons, located in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, which, in mice, affects both the state of sevoflurane anesthesia and a grooming behavior observed after it. PVHCRH neurons showed elevated calcium activity during the post-anesthesia period. Optogenetic activation of these PVHCRH neurons during sevoflurane anesthesia shifts the EEG from burst-suppression to a seemingly activated state (an apparent arousal effect), although without a behavioral correlate. Chemogenetic activation of the PVHCRH neurons delays sevoflurane-induced loss of righting reflex (another apparent arousal effect). On the other hand, chemogenetic inhibition of PVHCRH neurons delays recovery of righting reflex and decreases sevoflurane-induced stress (an apparent decrease in the …

Joint Public Review:

This study describes a group of CRH-releasing neurons, located in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, which, in mice, affects both the state of sevoflurane anesthesia and a grooming behavior observed after it. PVHCRH neurons showed elevated calcium activity during the post-anesthesia period. Optogenetic activation of these PVHCRH neurons during sevoflurane anesthesia shifts the EEG from burst-suppression to a seemingly activated state (an apparent arousal effect), although without a behavioral correlate. Chemogenetic activation of the PVHCRH neurons delays sevoflurane-induced loss of righting reflex (another apparent arousal effect). On the other hand, chemogenetic inhibition of PVHCRH neurons delays recovery of righting reflex and decreases sevoflurane-induced stress (an apparent decrease in the arousal effect). The authors conclude that PVHCRH neurons "integrate" sevoflurane-induced anesthesia and stress. The authors also claim that their findings show that sevoflurane itself produces a post-anesthesia stress response that is independent of any surgical trauma, such as an incision. In its revised form, the article does not achieve its intended goal and will not have impact on the clinical practice of anesthesiology nor on anesthesiology research.

Strengths:

The manuscript uses targeted manipulation of the PVHCRH neurons with state-of-the-art methods and is technically sound. Also, the number of experiments is substantial.

Weaknesses:

The most significant weaknesses remain: a) overinterpretation of the significance of their findings b) the failure to use another anesthetic as a control, c) a failure to compellingly link their post-sevoflurane measures in mice to anything measured in humans, and d) limitations in the novelty of the findings. These weaknesses are related to the primary concerns described below:

Concerns about the primary conclusion that PVHCRH neurons integrate the anesthetic effects and post-anesthesia stress response of sevoflurane GA:

It is important to compare the effects of sevoflurane with at least one other inhaled ether anesthetic as one step towards elevating the impact of this paper to the level required for a journal such as eLife. Isoflurane, desflurane, and enflurane are ether anesthetics that are very similar to each other, as well as being similar to sevoflurane. For example, one study cited by the authors (Marana et al. 2013) concludes that there is weak evidence for differences in stress-related hormones between sevoflurane and desflurane, with lower levels of cortisol and ACTH observed during the desflurane intraoperative period. It is important to determine whether desflurane activates PVHCRH neurons in the post-anesthesia period, and whether this is accompanied by excess grooming in the mice because this will distinguish whether the effects of sevoflurane generalize to other inhaled anesthestics, or, alternatively, relate to unique idiosyncratic properties of this gas that may not be a part of its anesthetic properties.

Concerns about the clinical relevance of the experiments:

In anesthesiology practice, perioperative stress observed in patients is more commonly related to the trauma of the surgical intervention, with inadequate levels of antinociception or unconsciousness intraoperatively and/or poor post-operative pain control. The authors seem to be suggesting that the sevoflurane itself is causing stress because their mice receive sevoflurane but no invasive procedures, but there is no evidence of sevoflurane inducing stress in human patients. It is important to know whether sevoflurane effectively produces behavioral stress in the recovery room in patients that could be related to the putative stress response (excess grooming) observed in mice. For example, in surgeries or procedures which required only a brief period of unconsciousness that could be achieved by administering sevoflurane alone (comparable to the 30 min administered to the mice), is there clinical evidence of post-operative stress? It is also important to describe a rationale for using a 30 min sevoflurane exposure. What proportion of human surgeries using sevoflurane use exposure times that are comparable to this?

It is the experience of one of the reviewers that human patients who receive sevoflurane as the primary anesthetic do not wake up more stressed than if they had had one of the other GABAergic anesthetics. If there were signs of stress upon emergence (increased heart rate, blood pressure, thrashing movements) from general anesthesia, this would be treated immediately. The most likely cause of post-operative stress behaviors in humans is probably inadequate anti-nociception during the procedure, which translates into inadequate post-op analgesia and likely delirium. It is the case that children receiving sevoflurane do have a higher likelihood of post-operative delirium. Perhaps the authors' studies address a mechanism for delirium associated with sevoflurane, but this is barely mentioned. Delirium seems likely to be the closest clinical phenomenon to what was studied. As noted by the Besnier et al (2017) article cited by the authors, surgery can elevate postoperative glucocorticoid stress hormones, but it generally correlates with the intensity of the surgical procedure. Besnier et al also note the elevation of glucocorticoids is generally considered to be adaptive. Thus, reducing glucocorticoids during surgery with sevoflurane may hamper recovery, especially as it relates to tissue damage, which was not measured or considered here. This paper only considers glucocorticoid release as a negative factor, which causes "immunosuppression", "proteolysis", and "delays postoperative recovery and...leads to increased morbidity".

It is also the case that there are explicit published findings showing that mild and moderate surgical procedures in children receiving sevoflurane (which might be the closest human proxy to the brief 30 minute sevoflurane exposure used here) do not have elevated cortisol (Taylor et al, J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2013). This again raises the question of whether the enhanced grooming or elevated corticosterone observed in the mice here has any relevance to humans.

Concerns about the novelty of the findings:

The key finding here is that CRH neurons mediate measures of arousal, and arousal modulates sevoflurane anesthesia induction and recovery. However, CRH is associated with arousal in numerous studies. In fact, the authors' own work, published in eLife in 2021, showed that stimulating the hypothalamic CRH cells lead to arousal and their inhibition promoted hypersomnia. In both papers the authors use fos expression in CRH cells during a specific event to implicate the cells, then manipulate them and measure EEG responses. In the previous work, the cells were active during wakefulness; here- they were active in the awake state the follows anesthesia (Figure 1). Thus, the findings in the current work are incremental and not particularly impactful. Claims like "Here, a core hypothalamic ensemble, corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, is discovered" are overstated. PVHCRH cell populations were discovered in the 1980s. Suggesting that it is novel to identify that hypothalamic CRH cells regulate post-anesthesia stress is unfounded as well: this PVH population has been shown over four decades to regulate a plethora of different responses to stress. Anesthesia stress is no different. Their role in arousal is not being discovered in this paper. Even their role in grooming is not discovered in this paper.

The activation of CRH cells in PVH has already been shown to result in grooming by Jaideep Bains (a paper cited by the authors). Thus, the involvement of these cells in this behavior is not surprising. The authors perform elaborate manipulations of CRH cells and numerous analyses of grooming and related behaviors. For example, they compare grooming and paw licking after anesthesia with those after other stressors such as forced swim, spraying mice with water, physical attack and restraint. The authors have identified a behavioral phenomenon in a rodent model that does not have a clear correlation with a behavior state observed in humans during the use of sevoflurane as part of an anesthetic regimen. The grooming behaviors are not a model of the emergence delirium or the cognitive dysfunction observed commonly in patients receiving sevoflurane for general anesthesia. Emergence delirium is commonly seen in children after sevoflurane is used as part of general anesthesia and cognitive dysfunction is commonly observed in adults-particularly the elderly -- following general anesthesia.

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

Public reviews

This study describes a group of CRH-releasing neurons, located in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, which, in mice, affects both the state of sevoflurane anesthesia and a grooming behavior observed after it. PVHCRH neurons showed elevated calcium activity during the post-anesthesia period. Optogenetic activation of these PVHCRH neurons during sevoflurane anesthesia shifts the EEG from burst-suppression to a seemingly activated state (an apparent arousal effect), although without a behavioral correlate. Chemogenetic activation of the PVHCRH neurons delays sevoflurane-induced loss of righting reflex (another apparent arousal effect). On the other hand, chemogenetic inhibition of PVHCRH neurons delays recovery of righting reflex …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

Public reviews

This study describes a group of CRH-releasing neurons, located in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, which, in mice, affects both the state of sevoflurane anesthesia and a grooming behavior observed after it. PVHCRH neurons showed elevated calcium activity during the post-anesthesia period. Optogenetic activation of these PVHCRH neurons during sevoflurane anesthesia shifts the EEG from burst-suppression to a seemingly activated state (an apparent arousal effect), although without a behavioral correlate. Chemogenetic activation of the PVHCRH neurons delays sevoflurane-induced loss of righting reflex (another apparent arousal effect). On the other hand, chemogenetic inhibition of PVHCRH neurons delays recovery of righting reflex and decreases sevoflurane-induced stress (an apparent decrease in the arousal effect). The authors conclude that PVHCRH neurons "integrate" sevoflurane-induced anesthesia and stress. The authors also claim that their findings show that sevoflurane itself produces a post-anesthesia stress response that is independent of any surgical trauma, such as an incision. In its revised form, the article does not achieve its intended goal and will not have impact on the clinical practice of anesthesiology nor on anesthesiology research.

Thanks for the reviews. Please see our responses to the following comments.

Weaknesses:

The most significant weaknesses remain:

a) overinterpretation of the significance of their findings

b) the failure to use another anesthetic as a control,

c) a failure to compellingly link their post-sevoflurane measures in mice to anything measured in humans, and

d) limitations in the novelty of the findings. These weaknesses are related to the primary concerns described below:

Concerns about the primary conclusion that PVHCRH neurons integrate the anesthetic effects and post-anesthesia stress response of sevoflurane GA

(1) After revision, their remain multiple places where it is claimed that PVHCRH neurons mediate the anesthetic effects of sevoflurane (impact statement: we explain "how sevoflurane-induced general anesthesia works..."; introduction: "the neuronal mechanisms that mediate the anesthetic effects...of sevoflurane GA remain poorly understood" and "PVHCRH neurons may act as a crucial node integrating the anesthetic effect and stress response of sevoflurane").The manuscript simply does not support these statements. The authors show that a short duration exposure to sevoflurane inhibits PVHCRH neurons, but this is followed by hyperexcitability of these neurons for a short period after anesthesia is terminated. They show that the induction and recovery from sevoflurane anesthesia can be modulated by PVHCRH neuronal activity, most likely through changes in brain state (measured by EEG). They also show that PVHCRH neuronal activity modulates corticosterone levels and grooming behavior observed post-anesthesia (which the authors argue are two stress responses).These two things (effects during anesthesia and effects post-anesthesia)may be mechanistically unrelated to each other. None of these observations relate to the primary mechanism of action for sevoflurane. All claims relating to "anesthetic effects" should be removed. Even the term "integration" seems wrong-it implies the PVH is combining information about the anesthetic effect and post-anesthesia stress responses.

As requested, we have removed all claims related to ‘anesthetic effects’ or ‘integration’. Please see the revised manuscript.

(2) lt is important to compare the effects of sevoflurane with at least one other inhaled ether anesthetic as one step towards elevating the impact of this paper to the level required for a journal such as eLife. Isoflurane, desflurane, and enflurane are ether anesthetics that are very similar to each other, as well as being similar to sevoflurane. For example, one study cited by the authors (Marana et al.2013) concludes that there is weak evidence for differences in stress-related hormones between sevoflurane and desflurane, with lower levels of cortisol and ACTH observed during the desflurane intraoperative period. It is important to determine whether desflurane activates PVHCRH neurons in the post-anesthesia period, and whether this is accompanied by excess grooming in the mice, because this will distinguish whether the effects of sevoflurane generalize to other inhaled anesthestics, or, alternatively, relate to unique idiosyncratic properties of this gas that may not be a part of its anesthetic properties.

Thanks for your insightful comments and suggestions. Regarding your request for additional experiments, we acknowledge the value they could add to our study. However, investigating whether the effects of sevoflurane generalize to other inhaled anesthetics is beyond the scope of our current study. There is evidence indicating the prevalence of anesthetic stress caused by inhaled ether anesthetics1,2. The post-anesthesia stress-related behaviors caused by sevoflurane administration are reminiscent of delirium observed clinically. Notably, studies have shown that the use of desflurane for maintenance of anesthesia did not significantly affect the incidence or duration of delirium compared to sevoflurane administration3. This suggests that our observations likely represent a generalized response to inhaled ether anesthetic rather than being specific to sevoflurane.

Concerns about the clinical relevance of the experiments

In anesthesiology practice, perioperative stress observed in patients is more commonly related to the trauma of the surgical intervention, with inadequate levels of antinociception or unconsciousness intraoperatively and/or poor post-operative pain control. The authors seem to be suggesting that the sevoflurane itself is causing stress because their mice receive sevoflurane but no invasive procedures, but there is no evidence of sevoflurane inducing stress in human patients. It is important to know whether sevoflurane effectively produces behavioral stress in the recovery room in patients that could be related to the putative stress response (excess grooming) observed in mice. For example, in surgeries or procedures which required only a brief period of unconsciousness that could be achieved by administering sevoflurane alone (comparable to the 30 min administered to the mice), is there clinical evidence of post-operative stress? It is also important to describe a rationale for using a 30 min sevoflurane exposure. What proportion of human surgeries using sevoflurane use exposure times that are comparable to this?

It is also the case that there are explicit published findings showing that mild and moderate surgical procedures in children receiving sevoflurane (which might be the closest human proxy to the brief 30 minutes sevoflurane exposure used here) do not have elevated cortisol (Taylor et al, J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2013). This again raises the question of whether the enhanced grooming or elevated corticosterone observed in the mice here has any relevance to humans.

Thanks for the comments. Most ear, nose, and throat surgeries in children involve a short period of anesthesia with sevoflurane alone4-6, which is similar to the 30-minute exposure in our mouse study. In clinical settings, emergence delirium and agitation are common in young children undergoing sevoflurane anesthesia7, often accompanied by troublesome excitation phenomena during induction and awakening8. These clinical observations align with the post-operative stress response (e.g., excessive grooming) we identified in our study.

It is the experience of one of the reviewers that human patients who receive sevoflurane as the primary anesthetic do not wake up more stressed than if they had had one of the other GABAergic anesthetics. If there were signs of stress upon emergence (increased heart rate, blood pressure, thrashing movements) from general anesthesia, this would be treated immediately. The most likely cause of post-operative stress behaviors in humans is probably inadequate anti-nociception during the procedure, which translates into inadequate post-op analgesia and likely delirium. It is the case that children receiving sevoflurane do have a higher likelihood of post-operative delirium. Perhaps the authors' studies address a mechanism for delirium associated with sevoflurane, but this is barely mentioned. Delirium seems likely to be the closest clinical phenomenon to what was studied. As noted by the Besnier et al (2017) article cited by the authors, surgery can elevate postoperative glucocorticoidstress hormones, but it generally correlates with the intensity of the surgical procedure. Besnier et al also note the elevation of glucocorticoids is generally considered to be adaptive. Thus, reducing glucocorticoids during surgery with sevoflurane may hamper recovery, especially as it relates to tissue damage, which was not measured or considered here. This paper only considers glucocorticoid release as a negative factor, which causes "immunosuppression", "proteolysis", and "delays postoperative recovery and leads to increased morbidity".

Thanks for the comments. We agree that the post-anesthetic stress behaviors mentioned in our manuscript are similar to the clinical phenomenon of delirium, which were defined in Cheng Li’s study as ‘sevoflurane-induced post-operative delirium’9. Therefore, we conducted additional behavioral tests for cognitive function, including the Y-maze and novel object recognition test, in mice administrated 30-minute sevoflurane anesthesia. The results demonstrate that chemogenetic inhibition of PVHCRH neurons ameliorated the short-term memory impairment in mice exposed to 30-minute sevoflurane GA (Figure 7-figure supplement 9), suggesting PVHCRH neurons may involve in modulating sevoflurane-induced postoperative delirium.

Concerns about the novelty of the findings:

The key finding here is that CRH neurons mediate measures of arousal, and arousal modulates sevoflurane anesthesia induction and recovery. However, CRH is associated with arousal in numerous studies. In fact, the authors' own work, published in eLife in 2021, showed that stimulating the hypothalamic CRH cells lead to arousal and their inhibition promoted hypersomnia. In both papers the authors use fos expression in CRH cells during a specific event to implicate the cells, then manipulate them and measure EEG responses. In the previous work, the cells were active during wakefulness; here- they were active in the awake state the follows anesthesia (Figure1). Thus, the findings in the current work are incremental and not particularly impactful. Claims like "Here, a core hypothalamic ensemble, corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, is discovered" are overstated. PVHCRH cell populations were discovered in the 1980s. Suggesting that it is novel to identify that hypothalamic CRH cells regulate post-anesthesia stress is unfounded as well: this PVH population has been shown over four decades to regulate a plethora of different responses to stress. Anesthesia stress is no different. Their role in arousal is not being discovered in this paper. Even their role in grooming is not discovered in this paper.

Thanks for the comments. As requested, we have revised our manuscript by removing overstated sentences. Please see the revised manuscript. In terms of novelty, our study reveals that PVHCRH neurons are implicated not only in the induction and emergence of sevoflurane general anesthesia but also in sevoflurane-induced post-operative delirium. This finding represents a novel contribution to the field, as it has not been previously reported by other studies.

The activation of CRH cells in PVH has already been shown to result in grooming by Jaideep Bains (a paper cited by the authors). Thus, the involvement of these cells in this behavior is not surprising. The authors perform elaborate manipulations of CRH cells and numerous analyses of grooming and related behaviors. For example, they compare grooming and paw licking after anesthesia with those after other stressors such as forced swim, spraying mice with water, physical attack and restraint. The authors have identified a behavioral phenomenon in a rodent model that does not have a clear correlation with a behavior state observed in humans during the use of sevoflurane as part of an anesthetic regimen. The grooming behaviors are not a model of the emergence delirium or the cognitive dysfunction observed commonly in patients receiving sevoflurane for general anesthesia. Emergence delirium is commonly seen in children after sevoflurane is used as part of general anesthesia and cognitive dysfunction is commonly observed in adults-particularly the elderly-- following general anesthesia. No features of delirium or cognitive dysfunction are measured here.

As requested, behavioral tests for cognitive function have been conducted and displayed in Figure 7-figure supplement 9.

Other concerns:

In Figure 2, cFos was measured in the PVH at different points before, during and after sevoflurane. The greatest cFos expression was seen in Post 2, the latest time point after anesthesia. However, this may simply reflect the fact that there is a delay between activity levels and expression of cFos (as noted by the authors, 2-3 hours). Thus, sacrificing mice 30 minutes after the onset of sevoflurane application would be expected to drive minimal cFos expression, and the cFos observed at 30 minutes would not accurately reflect the activity levels during the sevoflurane. Also, the authors state that the hyperactivity, as measured by cFos, lasted "approximately 1 hours before returning to baseline", but there is no data to support this return to baseline.

Thanks for the comments. We apologize that the protocol we used for c-fos staining may not accurately reflect the activity levels, so we have removed Figure 2F. The sentence ‘lasted approximately 1 hours before returning to baseline’ refers to the calcium signal but not c-fos level.

In Figure 7, the number of animals appears to change from panel to panel even though they are supposed to show animals from the same groups. For example, cort was measured in only 3 saline-treated O2 animals (Fig 7E), but cFos and CRH were assessed in 4 (Fig C,D). Similarly, grooming time and time spent in open arms was measured in 6 saline-treated O2 controls (Fig 7F, H) but central distance was measured in 8(Fig 7G). There are other group number discrepancies in this figure--the number of data points in the plots do not match what is reported in the legend for numerous groups. Similarly, Figure 4 has a mismatch between the Ns reported in the legend and the number of points plotted per bar. For example, there were 10 animals in the hM3Di group; all are shown for the LORR and time to emergence plots, but only8 were used for time to induction. The legends reported N=7 for the mCherry group, yet 9 are shown for the time to emergence panel. No reason for exclusions is cited. These figures (and their statistics) should be corrected.

Thanks for the comments. We have rechecked and corrected our figures and illustrations in the revised manuscript.

Recommendations for the authors:

In Figure 6, the BSR pre-stim data points for panels F and H look exactly identical, even though these data are from two different sets of mice. It seems likely that one of these panels is not depicting the correct pre-stim data points. Please check this.

Thanks for the comments. We have corrected this mistake.

General anesthesia is a combination of behavioral and physiological states induced and maintained primarily by pharmacologic agents. The authors do not provide a definition of general anesthesia.

Thanks for the advice. We have added the definition of general anesthesia in the introduction part.

The first sentence of the abstract closely resembles the first sentence of the abstract of Brown,Purdon and Van Dort,Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2011,34:601-28 yet, there is no citation.

Thanks for the comments. We have revised the first sentence.

ln the Discussion, the authors cite the research on circuitry that is relevant for emergence from general anesthesia. Conspicuously missing from this section of the paper is the large body of work by Solt and colleagues which has demonstrated that dopamine agonists (such as methylphenidate), electrical stimulation of the ventral tegmental area and optogenetic stimulation of the D1 neurons in the ventral tegmental area can hasten emergence from general anesthesia. Also omitted is the work of Kelzand colleagues and a discussion of neural inertia.

Thanks for the suggestions. We have added these citations as requested.

As regards the weaknesses of p-values for reporting the results of scientific studies, l offer the following reference to the authors. Ronald L. Wasserstein & Nicole A.Lazar (2016)The ASA Statement on p-Values: Context, Process, and Purpose, The American Statistician,70:2,129- 133, DOl:10.1080/00031305.2016.1154108

Thanks for the suggestions. We have revised the manuscript as requested.

The methods for the CRF antibody are unclear. It was previously suggested that the antibody be validated (for example, show an absence of immunostaining with CRF knockdown) because the concentration of antiserum (1:800) is quite high, suggesting either the antibody is not potent or (more concerning) not specific. The methods also indicated that colchicine was infused ICV prior to perfusion for staining of cFos and CRF, but no surgical methods are described that would enable ICV infusion, and it is not clear why colchicine was used. Please clarify.

The anti-CRF antibody is validated by other studies11,12. F For CRF immunostaining, animals' brains were pre-treated with intraventricular injections of colchicine (20 μg in 500 nL saline) 24 hours before perfusion to inhibit fast axonal transport13,14. Additional details regarding these methods have been included in the Method section of the revised manuscript.

Editor's note:

Full statistical reporting including exact p-values alongside summary statistics (test statistic and df) and 95% confidence intervals is lacking.

Thanks for the suggestions. We have added full statistical reporting in the revised manuscript as requested.

Reference

(1) Marana, E. et al. Desflurane versus sevoflurane: a comparison on stress response. Minerva Anestesiol 79, 7-14 (2013).

(2) Yang, L., Chen, Z. & Xiang, D. Effects of intravenous anesthesia with sevoflurane combined with propofol on intraoperative hemodynamics, postoperative stress disorder and cognitive function in elderly patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery. Pak J Med Sci 38, 1938-1944, doi:10.12669/pjms.38.7.5763 (2022).

(3) Driscoll, J. N. et al. Comparing incidence of emergence delirium between sevoflurane and desflurane in children following routine otolaryngology procedures. Minerva Anestesiol 83, 383-391, doi:10.23736/s0375-9393.16.11362-8 (2017).

(4) Galinkin, J. L. et al. Use of intranasal fentanyl in children undergoing myringotomy and tube placement during halothane and sevoflurane anesthesia. Anesthesiology 93, 1378-1383, doi:10.1097/00000542-200012000-00006 (2000).

(5) Greenspun, J. C., Hannallah, R. S., Welborn, L. G. & Norden, J. M. Comparison of sevoflurane and halothane anesthesia in children undergoing outpatient ear, nose, and throat surgery. J Clin Anesth 7, 398-402, doi:10.1016/0952-8180(95)00071-o (1995).

(6) Messieha, Z. Prevention of sevoflurane delirium and agitation with propofol. Anesth Prog 60, 67-71, doi:10.2344/0003-3006-60.3.67 (2013).

(7) Shi, M. et al. Dexmedetomidine for the prevention of emergence delirium and postoperative behavioral changes in pediatric patients with sevoflurane anesthesia: a double-blind, randomized trial. Drug Des Devel Ther 13, 897-905, doi:10.2147/dddt.S196075 (2019).

(8) Veyckemans, F. Excitation and delirium during sevoflurane anesthesia in pediatric patients. Minerva Anestesiol 68, 402-405 (2002).

(9) Xu, Y., Gao, G., Sun, X., Liu, Q. & Li, C. ATPase Inhibitory Factor 1 Is Critical for Regulating Sevoflurane-Induced Microglial Inflammatory Responses and Caspase-3 Activation. Front Cell Neurosci 15, 770666, doi:10.3389/fncel.2021.770666 (2021).

(10) Friedman, E. B. et al. A conserved behavioral state barrier impedes transitions between anesthetic-induced unconsciousness and wakefulness: evidence for neural inertia. PLoS One 5, e11903, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0011903 (2010).

(11) Giardino, W. J. et al. Parallel circuits from the bed nuclei of stria terminalis to the lateral hypothalamus drive opposing emotional states. Nat Neurosci 21, 1084-1095, doi:10.1038/s41593-018-0198-x (2018).

(12) Yeo, S. H., Kyle, V., Blouet, C., Jones, S. & Colledge, W. H. Mapping neuronal inputs to Kiss1 neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the mouse. PLoS One 14, e0213927, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0213927 (2019).

(13) de Goeij, D. C. et al. Repeated stress-induced activation of corticotropin-releasing factor neurons enhances vasopressin stores and colocalization with corticotropin-releasing factor in the median eminence of rats. Neuroendocrinology 53, 150-159, doi:10.1159/000125712 (1991).

(14) Yuan, Y. et al. Reward Inhibits Paraventricular CRH Neurons to Relieve Stress. Curr Biol 29, 1243-1251.e1244, doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.02.048 (2019).

-

-

eLife assessment

This study presents useful findings that describe how activity in the corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVHCRH neurons) modulates sevoflurane anesthesia, as well as a phenomenon the authors term a "sevoflurane general anesthetic-elicited stress response". The technical approaches are solid, and the data presented is largely clear. However, the primary conclusion, that the PVHCRH neurons are critical for the mechanisms of sevoflurane anesthesia, is incompletely supported by the data.

-

Joint Public Review:

This study describes a group of CRH-releasing neurons, located in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, which, in mice, affects both the state of sevoflurane anesthesia and a grooming behavior observed after it. PVHCRH neurons showed elevated calcium activity during the post-anesthesia period. Optogenetic activation of these PVHCRH neurons during sevoflurane anesthesia shifts the EEG from burst-suppression to a seemingly activated state (an apparent arousal effect), although without a behavioral correlate. Chemogenetic activation of the PVHCRH neurons delays sevoflurane-induced loss of righting reflex (another apparent arousal effect). On the other hand, chemogenetic inhibition of PVHCRH neurons delays recovery of righting reflex and decreases sevoflurane-induced stress (an apparent decrease in the …

Joint Public Review:

This study describes a group of CRH-releasing neurons, located in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, which, in mice, affects both the state of sevoflurane anesthesia and a grooming behavior observed after it. PVHCRH neurons showed elevated calcium activity during the post-anesthesia period. Optogenetic activation of these PVHCRH neurons during sevoflurane anesthesia shifts the EEG from burst-suppression to a seemingly activated state (an apparent arousal effect), although without a behavioral correlate. Chemogenetic activation of the PVHCRH neurons delays sevoflurane-induced loss of righting reflex (another apparent arousal effect). On the other hand, chemogenetic inhibition of PVHCRH neurons delays recovery of righting reflex and decreases sevoflurane-induced stress (an apparent decrease in the arousal effect). The authors conclude that PVHCRH neurons "integrate" sevoflurane-induced anesthesia and stress. The authors also claim that their findings show that sevoflurane itself produces a post-anesthesia stress response that is independent of any surgical trauma, such as an incision. In its revised form, the article does not achieve its intended goal and will not have impact on the clinical practice of anesthesiology nor on anesthesiology research.

Strengths:

The manuscript uses targeted manipulation of the PVHCRH neurons with state-of-the-art methods, and is technically sound. Also, the number of experiments is substantial.

Weaknesses:

The most significant weaknesses remain: a) overinterpretation of the significance of their findings b) the failure to use another anesthetic as a control, c) a failure to compellingly link their post-sevoflurane measures in mice to anything measured in humans, and d) limitations in the novelty of the findings. These weaknesses are related to the primary concerns described below:

Concerns about the primary conclusion that PVHCRH neurons integrate the anesthetic effects and post-anesthesia stress response of sevoflurane GA:

After revision, their remain multiple places where it is claimed that PVHCRH neurons mediate the anesthetic effects of sevoflurane (impact statement: we explain "how sevoflurane-induced general anesthesia works..."; introduction: "the neuronal mechanisms that mediate the anesthetic effects...of sevoflurane GA remain poorly understood" and "PVHCRH neurons may act as a crucial node integrating the anesthetic effect and stress response of sevoflurane"). The manuscript simply does not support these statements. The authors show that a short duration exposure to sevoflurane inhibits PVHCRH neurons, but this is followed by hyperexcitability of these neurons for a short period after anesthesia is terminated. They show that the induction and recovery from sevoflurane anesthesia can be modulated by PVHCRH neuronal activity, most likely through changes in brain state (measured by EEG). They also show that PVHCRH neuronal activity modulates corticosterone levels and grooming behavior observed post-anesthesia (which the authors argue are two stress responses). These two things (effects during anesthesia and effects post-anesthesia) may be mechanistically unrelated to each other. None of these observations relate to the primary mechanism of action for sevoflurane. All claims relating to "anesthetic effects" should be removed. Even the term "integration" seems wrong-it implies the PVH is combining information about the anesthetic effect and post-anesthesia stress responses.

It is important to compare the effects of sevoflurane with at least one other inhaled ether anesthetic as one step towards elevating the impact of this paper. Isoflurane, desflurane, and enflurane are ether anesthetics that are very similar to each other, as well as being similar to sevoflurane. For example, one study cited by the authors (Marana et al. 2013) concludes that there is weak evidence for differences in stress-related hormones between sevoflurane and desflurane, with lower levels of cortisol and ACTH observed during the desflurane intraoperative period. It is important to determine whether desflurane activates PVHCRH neurons in the post-anesthesia period, and whether this is accompanied by excess grooming in the mice, because this will distinguish whether the effects of sevoflurane generalize to other inhaled anesthestics, or, alternatively, relate to unique idiosyncratic properties of this gas that may not be a part of its anesthetic properties.

Concerns about the clinical relevance of the experiments:

In anesthesiology practice, perioperative stress observed in patients is more commonly related to the trauma of the surgical intervention, with inadequate levels of antinociception or unconsciousness intraoperatively and/or poor post-operative pain control. The authors seem to be suggesting that the sevoflurane itself is causing stress because their mice receive sevoflurane but no invasive procedures, but there is no evidence of sevoflurane inducing stress in human patients. It is important to know whether sevoflurane effectively produces behavioral stress in the recovery room in patients that could be related to the putative stress response (excess grooming) observed in mice. For example, in surgeries or procedures which required only a brief period of unconsciousness that could be achieved by administering sevoflurane alone (comparable to the 30 min administered to the mice), is there clinical evidence of post-operative stress? It is also important to describe a rationale for using a 30 min sevoflurane exposure. What proportion of human surgeries using sevoflurane use exposure times that are comparable to this?

It is the experience of one of the reviewers that human patients who receive sevoflurane as the primary anesthetic do not wake up more stressed than if they had had one of the other GABAergic anesthetics. If there were signs of stress upon emergence (increased heart rate, blood pressure, thrashing movements) from general anesthesia, this would be treated immediately. The most likely cause of post-operative stress behaviors in humans is probably inadequate anti-nociception during the procedure, which translates into inadequate post-op analgesia and likely delirium. It is the case that children receiving sevoflurane do have a higher likelihood of post-operative delirium. Perhaps the authors' studies address a mechanism for delirium associated with sevoflurane, but this is barely mentioned. Delirium seems likely to be the closest clinical phenomenon to what was studied. As noted by the Besnier et al (2017) article cited by the authors, surgery can elevate postoperative glucocorticoid stress hormones, but it generally correlates with the intensity of the surgical procedure. Besnier et al also note the elevation of glucocorticoids is generally considered to be adaptive. Thus, reducing glucocorticoids during surgery with sevoflurane may hamper recovery, especially as it relates to tissue damage, which was not measured or considered here. This paper only considers glucocorticoid release as a negative factor, which causes "immunosuppression", "proteolysis", and "delays postoperative recovery and...leads to increased morbidity".

It is also the case that there are explicit published findings showing that mild and moderate surgical procedures in children receiving sevoflurane (which might be the closest human proxy to the brief 30 minute sevoflurane exposure used here) do not have elevated cortisol (Taylor et al, J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 2013). This again raises the question of whether the enhanced grooming or elevated corticosterone observed in the mice here has any relevance to humans.

Concerns about the novelty of the findings:

The key finding here is that CRH neurons mediate measures of arousal, and arousal modulates sevoflurane anesthesia induction and recovery. However, CRH is associated with arousal in numerous studies. In fact, the authors' own work, published in eLife in 2021, showed that stimulating the hypothalamic CRH cells lead to arousal and their inhibition promoted hypersomnia. In both papers the authors use fos expression in CRH cells during a specific event to implicate the cells, then manipulate them and measure EEG responses. In the previous work, the cells were active during wakefulness; here- they were active in the awake state the follows anesthesia (Figure 1). Thus, the findings in the current work are incremental and not particularly impactful. Claims like "Here, a core hypothalamic ensemble, corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, is discovered" are overstated. PVHCRH cell populations were discovered in the 1980s. Suggesting that it is novel to identify that hypothalamic CRH cells regulate post-anesthesia stress is unfounded as well: this PVH population has been shown over four decades to regulate a plethora of different responses to stress. Anesthesia stress is no different. Their role in arousal is not being discovered in this paper. Even their role in grooming is not discovered in this paper.

The activation of CRH cells in PVH has already been shown to result in grooming by Jaideep Bains (a paper cited by the authors). Thus, the involvement of these cells in this behavior is not surprising. The authors perform elaborate manipulations of CRH cells and numerous analyses of grooming and related behaviors. For example, they compare grooming and paw licking after anesthesia with those after other stressors such as forced swim, spraying mice with water, physical attack and restraint. The authors have identified a behavioral phenomenon in a rodent model that does not have a clear correlation with a behavior state observed in humans during the use of sevoflurane as part of an anesthetic regimen. The grooming behaviors are not a model of the emergence delirium or the cognitive dysfunction observed commonly in patients receiving sevoflurane for general anesthesia. Emergence delirium is commonly seen in children after sevoflurane is used as part of general anesthesia and cognitive dysfunction is commonly observed in adults-particularly the elderly-- following general anesthesia. No features of delirium or cognitive dysfunction are measured here.

Other concerns:

In Figure 2, cFos was measured in the PVH at different points before, during and after sevoflurane. The greatest cFos expression was seen in Post 2, the latest time point after anesthesia. However, this may simply reflect the fact that there is a delay between activity levels and expression of cFos (as noted by the authors, 2-3 hours). Thus, sacrificing mice 30 minutes after the onset of sevoflurane application would be expected to drive minimal cFos expression, and the cFos observed at 30 minutes would not accurately reflect the activity levels during the sevoflurane. Also, the authors state that the hyperactivity, as measured by cFos, lasted "approximately 1 hours before returning to baseline", but there is no data to support this return to baseline.

In Figure 7, the number of animals appears to change from panel to panel even though they are supposed to show animals from the same groups. For example, cort was measured in only 3 saline-treated O2 animals (Fig 7E), but cFos and CRH were assessed in 4 (Fig C,D). Similarly, grooming time and time spent in open arms was measured in 6 saline-treated O2 controls (Fig 7F,H) but central distance was measured in 8 (Fig 7G). There are other group number discrepancies in this figure-- the number of data points in the plots do not match what is reported in the legend for numerous groups. Similarly, Figure 4 has a mismatch between the Ns reported in the legend and the number of points plotted per bar. For example, there were 10 animals in the hM3Di group; all are shown for the LORR and time to emergence plots, but only 8 were used for time to induction. The legends reported N=7 for the mCherry group, yet 9 are shown for the time to emergence panel. No reason for exclusions is cited. These figures (and their statistics) should be corrected.

-

Author Response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

eLife assessment

This study presents potentially useful findings describing how activity in the corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus modulates sevoflurane anesthesia, as well as a phenomenon the authors term a "general anesthetic stress response". The technical approaches are solid and the data presented are largely clear. However, the primary conclusion, that the PVHCRH neurons are a mechanism of sevoflurane anesthesia, is inadequately supported.

We appreciate the editors and reviewers for their thorough assessment and constructive feedback. We have provided clarifications and updated the manuscripts to better interpret our results, please see below. As for the primary conclusion, we revised it as …

Author Response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

eLife assessment

This study presents potentially useful findings describing how activity in the corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus modulates sevoflurane anesthesia, as well as a phenomenon the authors term a "general anesthetic stress response". The technical approaches are solid and the data presented are largely clear. However, the primary conclusion, that the PVHCRH neurons are a mechanism of sevoflurane anesthesia, is inadequately supported.

We appreciate the editors and reviewers for their thorough assessment and constructive feedback. We have provided clarifications and updated the manuscripts to better interpret our results, please see below. As for the primary conclusion, we revised it as PVH CRH neurons potently modulate states of anaesthesia in sevoflurane general anesthesia, being a part of anaesthesia regulatory network of sevoflurane.

Combined Public Review:

This study describes a group of CRH-releasing neurons, located in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, which, in mice, affects both the state of sevoflurane anesthesia and a grooming behavior observed after it. PVH-CRH neurons showed elevated calcium activity during the post-anesthesia period. Optogenetic activation of these PVH-CRH neurons during sevoflurane anesthesia shifts the EEG from burst-suppression to a seemingly activated state (an apparent arousal effect), although without a behavioral correlate. Chemogenetic activation of the PVH-CRH neurons delays sevoflurane-induced loss of righting reflex (another apparent arousal effect). On the other hand, chemogenetic inhibition of PVH-CRH neurons delays recovery of the righting reflex and decreases sevoflurane-induced stress (an apparent decrease in the arousal effect). The authors conclude that PVH-CRH neurons are a common substrate for sevoflurane-induced anesthesia and stress. The PVH-CRH neurons are related to behavioral stress responses, and the authors claim that these findings provide direct evidence for a relationship between sevoflurane anesthesia and sevoflurane-mediated stress that might exist even when there is no surgical trauma, such as an incision. In its current form, the article does not achieve its intended goal.

Thank you for the detailed review. We have carefully considered your comments and have revised the manuscript to provide a clearer interpretation of our findings. Our findings indicate that PVH CRH neurons integrate the anesthetic effect and post-anesthesia stress response of sevoflurane (GA), providing new evidence for understanding the neuronal regulation of sevoflurane GA and identifying a potential brain target for further investigation into modulating the post-anesthesia stress response. However, we did not propose that there was a direct relationship between sevoflurane anesthesia and sevoflurane-mediated stress in the absence of incision. Our results mainly concluded that PVH CRH neurons integrate the anaesthetic effect and post-anaesthesia stress response of sevoflurane GA, which offers new evidence for the neuronal regulation of sevoflurane GA and provides an important but ignored potential cause of the post-anesthesia stress response.

Strengths:

The manuscript uses targeted manipulation of the PVH-CRH neurons, and is technically sound. Also, the number of experiments is substantial.

Thank you.

Weaknesses:

The most significant weaknesses are a) the lack of consideration and measurement of GABAergic mechanisms of sevoflurane anesthesia, b) the failure to use another anesthetic as a control, c) a failure to document a compelling post-anesthesia stress response to sevoflurane in humans, d) limitations in the novelty of the findings. These weaknesses are related to the primary concerns described below:

Concerns about the primary conclusion, that PVH-CRH neurons mediate "the anesthetic effects and post-anesthesia stress response of sevoflurane GA".

Thanks for the advice. Our responses are as below:

- Just because the activity of a given neural cell type or neural circuit alters an anesthetic's response, this does not mean that those neurons play a role in how the anesthetic creates its anesthetic state. For example, sevoflurane is commonly used in children. Its primary mechanism of action is through enhancement of GABA-mediated inhibition. Children with ADHD on Ritalin (a dopamine reuptake inhibitor) who take it on the day of surgery can often require increased doses of sevoflurane to achieve the appropriate anesthetic state. The mesocortical pathway through which Ritalin acts is not part of the mechanism of action of sevoflurane. Through this pathway, Ritalin is simply increasing cortical excitability making it more challenging for the inhibitory effects of sevoflurane at GABAergic synapses to be effective. Similarly, here, altering the activity of the PVHCRH neurons and seeing a change in anesthetic response to sevoflurane does not mean that these neurons play a role in the fundamental mechanism of this anesthetic's action. With the current data set, the primary conclusions should be tempered.

Thank you for your comments. Our results adequately uncover PVH CRH neurons that modulate the state of consciousness as well as the stress response in sevoflurane GA, but are insufficient to demonstrate that these neurons play a role in the underlying mechanism of sevoflurane anesthesia. We will revise our conclusions and make them concrete. The primary conclusion has been revised as PVH CRH neurons potently modulate states of anaesthesia in sevoflurane GA, being a part of the anaesthesia regulatory network of sevoflurane.

- It is important to compare the effects of sevoflurane with at least one other inhaled ether anesthetic. Isoflurane, desflurane, and enflurane are ether anesthetics that are very similar to each other, as well as being similar to sevoflurane. It is important to distinguish whether the effects of sevoflurane pertain to other anesthetics, or, alternatively, relate to unique idiosyncratic properties of this gas that may not be a part of its anesthetic properties.

For example, one study cited by the authors (Marana et al.. 2013) concludes that there is weak evidence for differences in stress-related hormones between sevoflurane and desflurane, with lower levels of cortisol and ACTH observed during the desflurane intraoperative period. It is not clear that this difference in some stress-related hormones is modeled by post-sevoflurane excess grooming in the mice, but using desflurane as a control could help determine this.

Thank you for your suggestions. We completely agree on the importance of determining whether the effects of sevoflurane apply to other anesthetics or arise from unique idiosyncratic attributes separate from its anesthetic properties. However, it is challenging to definitively conclude whether the effects of sevoflurane observed in our study extend to other inhaled anesthetics, even with desflurane as a control. While sevoflurane shares many common anesthetic properties with other inhalation agents, it also exhibits distinct characteristics and potential idiosyncrasies that set it apart from its counterparts. Regarding studies related to desflurane's impact on hormone levels or stress-like behaviors, one study involving 20 women scheduled for elective total abdominal hysterectomy demonstrated that there was no significant correlation between the intra-operative depth of anesthesia achieved with desflurane and the extent of the endocrine-metabolic stress response (as indicated by the concentrations of plasma cortisol, glucose, and lactate)1. Besides, a study conducted with mice suggested the abilities related to sensorimotor functions, anxiety and depression did not undergo significant changes after 7 days of anesthesia administered with 8.0% desflurane for 6 h2. Furthermore, a study involving 50 Caucasian women undergoing laparoscopic surgery for benign ovarian cysts demonstrated that in low stress surgery, desflurane, when compared to sevoflurane, exhibited superior control over the intraoperative cortisol and ACTH response 3. Based on these findings, we propose that the effect we observed in this study is likely attributed to the unique idiosyncratic properties of sevoflurane. We will conduct additional experiments to investigate this proposal with other commonly used anaesthetics in our future studies.

Concerns about the clinical relevance of the experiments

In anesthesiology practice, perioperative stress observed in patients is more commonly related to the trauma of the surgical intervention, with inadequate levels of antinociception or unconsciousness intraoperatively and/or poor post-operative pain control. The authors seem to be suggesting that the anesthetic itself is causing stress, but there is no evidence of this from human patients cited. We were not aware that this is a documented clinical phenomenon. It is important to know whether sevoflurane effectively produces behavioral stress in the recovery room in patients that could be related to the putative stress response (excess grooming) observed in mice. For example, in surgeries or procedures that required only a brief period of unconsciousness that could be achieved by administering sevoflurane alone (comparable to the 30 min administered to the mice), is there clinical evidence of post-operative stress?

Thank you for your question. There is currently no direct evidence available. Studies on sevoflurane in humans primarily focus on its use during surgical interventions, making it difficult to find studies that solely administer sevoflurane, as was done in our study with mice. Generally, a short anesthesia time refers to procedures that last less than one hour, while a long anesthesia time could be considered for procedures lasting several hours or more4. A study published in eLife investigated the patterns of reemerging consciousness and cognitive function in 30 healthy adults who underwent GA for three hours 5. This finding suggests that the cognitive dysfunction observed immediately and persistently after GA in healthy animals may not necessarily apply anesthesia and postoperative neurocognitive disorders could be influenced by factors other than GA, such as surgery or patient comorbidity. Therefore, further studies are needed to verify the post-operative stress in sevoflurane-only short time anesthesia.

Indeed, stress after surgeries can result from multiple factors aside from anesthesia, including pain, anxiety, inflammation, but what we want to illustrate in this study is that anesthesia could be one of these factors that we ignored in previous studies. In our current study, we did not propose that there was a direct relationship between sevoflurane anesthesia and sevoflurane-mediated stress without incision. We observed stress-related behavioural changes after exposure of sevoflurane GA in mouse model, indicating sevoflurane-mediated stress might exist without surgical trauma. Importantly, whether anesthetic administration alone will cause post-operative stress is worth studying in different species especially human.

Patients who receive sevoflurane as the primary anesthetic do not wake up more stressed than if they had had one of the other GABAergic anesthetics. If there were signs of stress upon emergence (increased heart rate, blood pressure, thrashing movements) from general anesthesia, the anesthesiologist would treat this right away. The most likely cause of post-operative stress behaviors in humans is probably inadequate anti-nociception during the procedure, which translates into inadequate post-op analgesia and likely delirium. It is the case that children receiving sevoflurane do have a higher likelihood of post-operative delirium. Perhaps the authors' studies address a mechanism for delirium associated with sevoflurane, but this is not considered. Delirium seems likely to be the closest clinical phenomenon to what was studied.

We agree with your idea. We aim to establish a connection between post-operative delirium in humans and stress-like behaviors observed in mice following sevoflurane anesthesia. Specifically, we have observed that the increased grooming behavior exhibited by mice after sevoflurane anesthesia resembles the fuzzy state of consciousness experienced during post-operative delirium6. In our discussion, we also emphasized the occurrence of sevoflurane-induced emergence agitation, a common phenomenon reported in clinical studies with an incidence of up to 80%. This state is characterized by hyperactivity, confusion, delirium, and emotional agitation 7,8. Meanwhile, in our experimental tests, namely the open field test (OFT) and elevated plus maze (EPM) test, we observed that mice exposed to sevoflurane inhalation displayed reduced movement distances during both the OFT and EPM tests (Figure 7G and I). These findings suggest a decline in behavioral activity similar to what is observed in cases of delirium.

Concerns about the novelty of the findings

CRH is associated with arousal in numerous studies. In fact, the authors' own work, published in eLife in 2021, showed that stimulating the hypothalamic CRH cells leads to arousal and their inhibition promotes hypersomnia. In both papers, the authors use fos expression in CRH cells during a specific event to implicate the cells, then manipulate them and measure EEG responses. In the previous work, the cells were active during wakefulness; here- they were active in the awake state that follows anesthesia (Figure 1). Thus, the findings in the current work are incremental.

Thank you for acknowledging our previous work focusing on the changes in the sleep-wake state of mice when PVH CRH neurons are manipulated. In this study, our primary objective was to identify the neuronal mechanisms mediating the anesthetic effects and post-anesthetic stress response of sevoflurane GA. While our study claims that activation of PVH CRH neurons leads to arousal, it provides evidence that PVH CRH neurons may play a role in the regulation of conscious states in GA. Our current findings uncover that PVH CRH neurons modulate the state of consciousness as well as the stress response in sevoflurane GA, and that the modulation of PVH CRH neurons bidirectionally altered the induction and recovery of sevoflurane GA. This identifies a new brain region involved in sevoflurane GA that goes beyond the arousal-related regions.

The activation of CRH cells in PVN has already been shown to result in grooming by Jaideep Bains (cited as reference 58). Thus, the involvement of these cells in this behavior is expected. The authors perform elaborate manipulations of CRH cells and numerous analyses of grooming and related behaviors. For example, they compare grooming and paw licking after anesthesia with those after other stressors such as forced swim, spraying mice with water, physical attack, and restraint. However, the relevance of these behaviors to humans and generalization to other types of anesthetics is not clear.

The hyperactivity of PVH CRH neurons and behavior (e.g., excessive self-grooming) in mice may partially mirror the observed agitation and underlying mechanisms during emergence from sevoflurane GA in patients. As mentioned in the Discussion section (page 16, lines 371-374), sevoflurane-induced emergence agitation represents a prevalent manifestation of the post-anesthesia stress response. It is frequently observed, with an incidence of up to 80% in clinical reports, and is characterized by hyperactivity, confusion, delirium, and emotional agitation7,8. Our aim in this study is to distinguish the excessive stress responses of patients to sevoflurane GA from stress triggered by other factors. Other stimuli, such as forced swimming, can be considered sources of both physical and emotional stress, which are associated with depression and anxiety in humans.

Regarding generalization to other types of anesthetics, we propose that the stress-related behavioral effects observed in this study might occur in cases of the administration of certain types of anesthetics. For example, one study showed that intravenous ketamine infusion (10 mg/kg, 2 hours) elevated plasma corticosterone and progesterone levels in rats, reducing locomotor activity (sedation) 9. The administration of intravenous anesthesia with propofol combined with sevoflurane caused greater postoperative stress than the single use of propofol10. However, desflurane, a common inhaled ether anesthetic, when compared to sevoflurane, was associated with better control of intraoperative cortisol and ACTH response in low-stress surgeries8. Thus, these behaviors observed after exposure to sevoflurane GA may be related to the post-anesthesia stress response in humans, which might also occur in cases of the administration of certain types of anesthetics.

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer 1

- The CRH-Cre mouse line should be validated. There are several lines of these mice, and their fidelity varies.

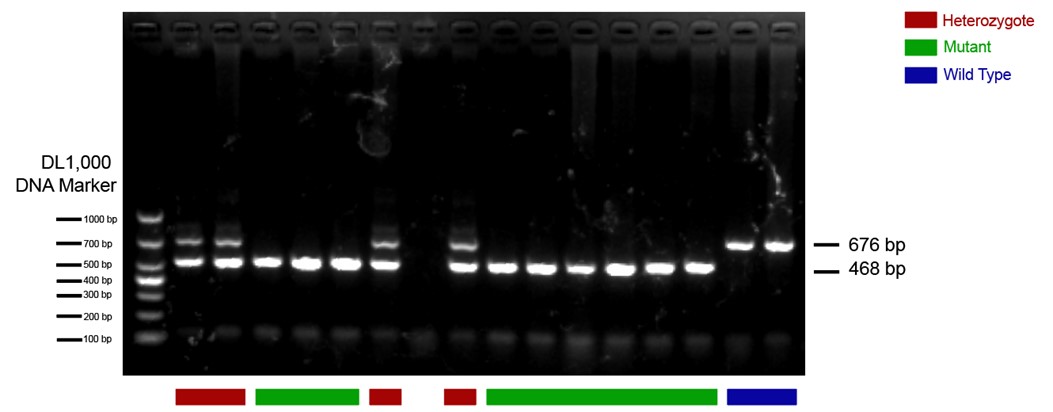

The CRH-Cre mouse line we used in this study is from The Jackson Laboratory (https://www.jax.org/strain/012704) with the name B6(Cg)-Crhtm1(cre)Zjh/J (Strain #: 012704). These CRH-ires-CRE knock-in mice have Cre recombinase expression directed to CRH positive neurons by the endogenous promoter/enhancer elements of the corticotropin releasing hormone locus (Crh). We have done standard PCR to validate the mouse line following genotyping protocols provided by the Jackson Laboratory. The protocol primers were: 10574 (SEQUENCE 5' → 3': CTT ACA CAT TTC GTC CTA GCC); 10575 (SEQUENCE 5' → 3': CAC GAC CAG GCT GCG GCT AAC); 10576 (SEQUENCE 5' → 3': CAA TGT ATC TTA TCA TGT CTG GAT CC). The 468-bp CRH-specific PCR product was amplified in mutant (CRH-Cre+/+) mice; in heterozygote (CRH-Cre+/-) mice, both the 468-bp and the 676-bp PCR products were detected; in wild type (WT) mice, only the 676-bp WT allele-specific PCR product was amplified. An example of PCR results is presented below. The heterozygote and mutant mice were included in our study.

Author response image 1.

- It would be very helpful to validate the CRH antibody. Using any antiserum at 1:800 suggests that it may not be potent or highly specific.

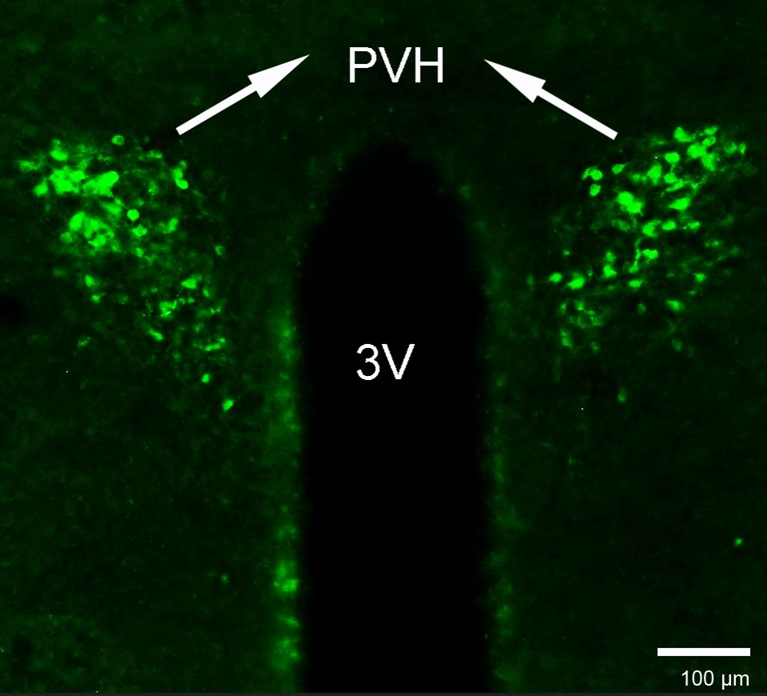

As requested, we used the same CRH antibody at a concentration of 1:800, following the methods described in the Method section. The results are displayed below.

Author response image 2.

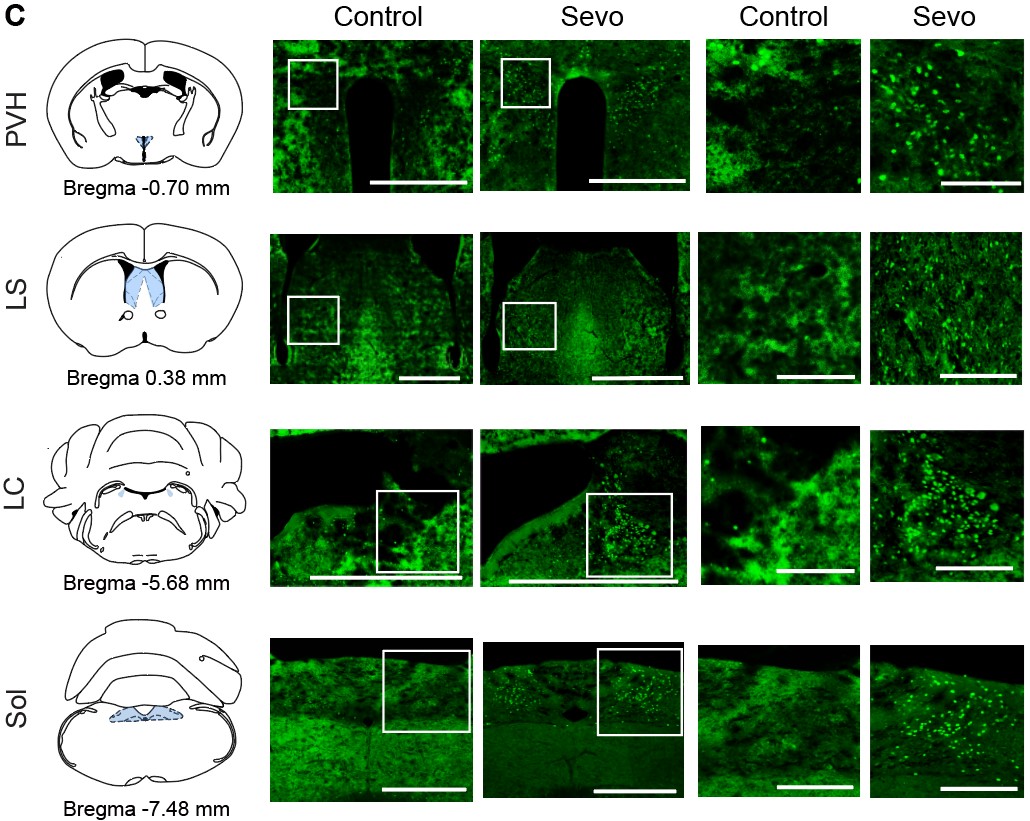

- In Figure 1C, the control sections are out of focus, any cells are blurry, reducing confidence in the analyses (locus ceruleus cells appear confluent in the control?)

Sorry for the confusing figure and we have revised the control section part of Figure 1C:

Author response image 3.

Reviewer 2

- In the Abstract, to say that "General anesthetics benefit patients undergoing surgeries without consciousness. ..." is a gross understatement of the essential role that general anesthesia plays today to make surgery not only tolerable but humane. This opening sentence should be rewritten. General anesthesia is a fundamental process required to undertake safely and humanely a high fraction of surgeries and invasive diagnostic procedures.

As requested, we rewrote this opening sentence, please see the follows:

GA is a fundamental process required to undertake surgeries and invasive diagnostic procedures safely and humanely. However, the undesired stress response associated with GA can lead to delayed recovery and even increased morbidity in clinical settings.

- In the Abstract, when discussing the response of the PVN-CRH neurons to chemogenetic inhibition, say exactly what the "opposite effect" is.

Thanks for your insights. We have rewritten our abstract as follows:

Chemogenetic activation of these neurons delayed the induction and accelerated emergence from sevoflurane GA, whereas chemogenetic inhibition of PVH CRH neurons promoted induction and prolonged emergence from sevoflurane GA.

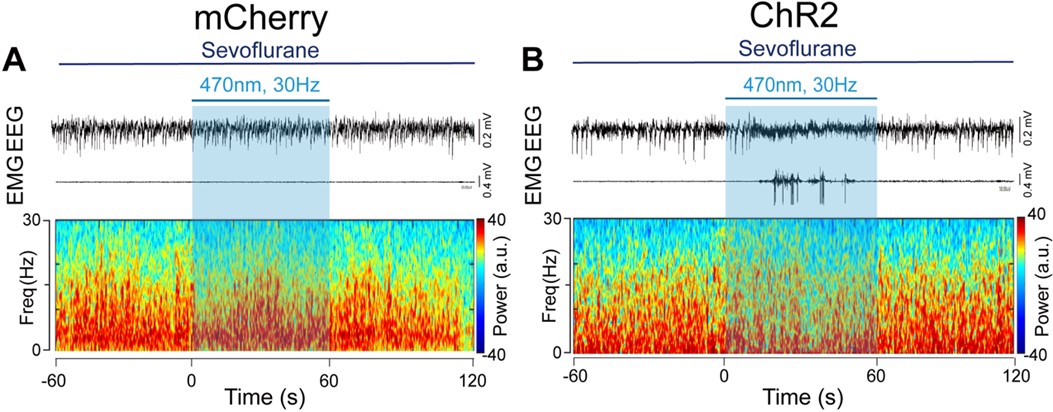

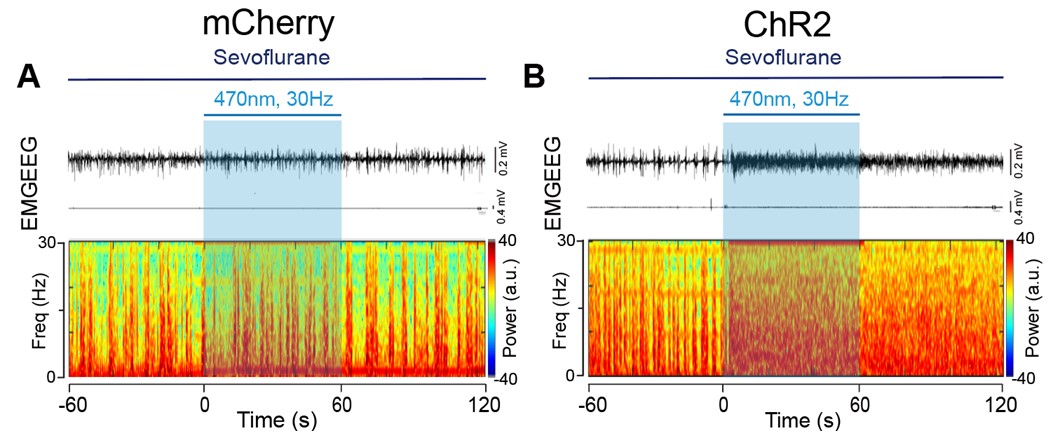

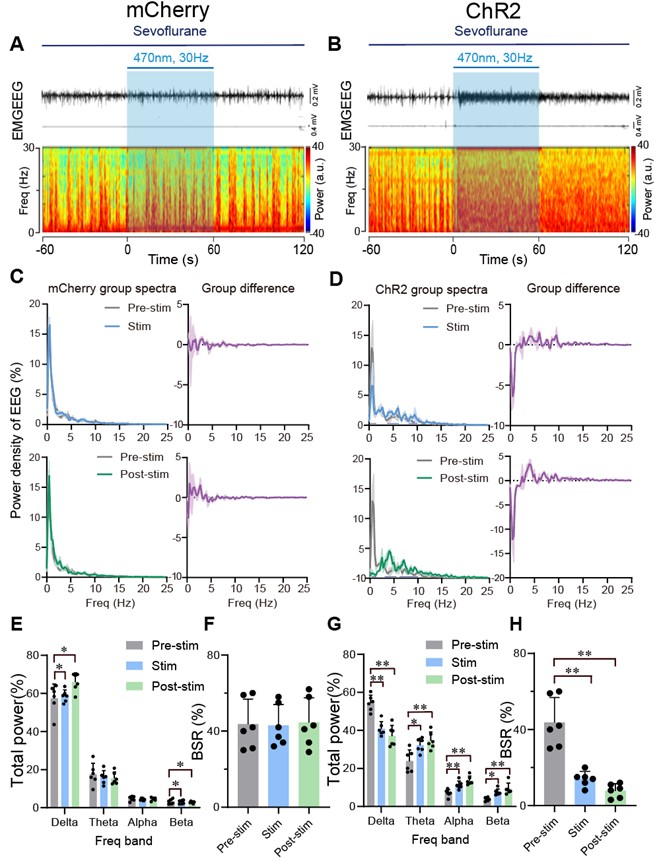

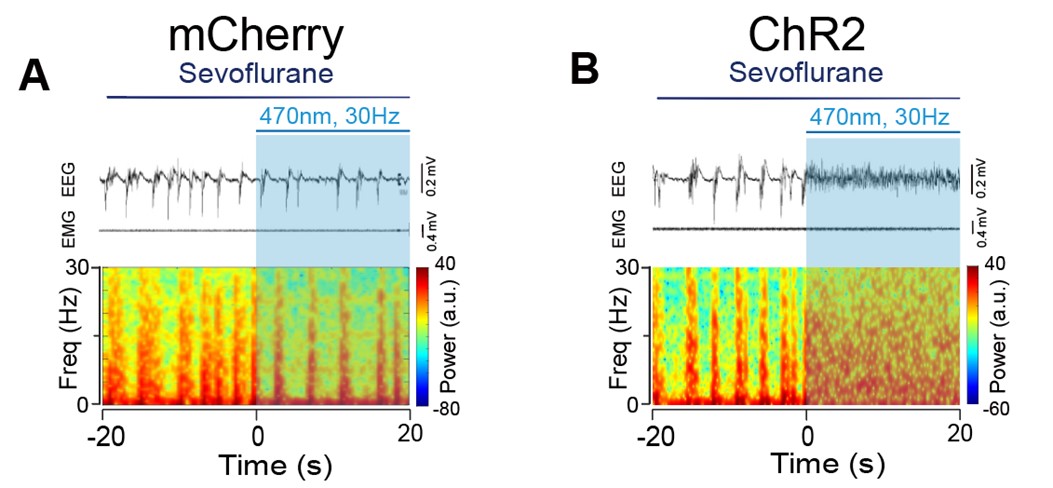

- In all spectrograms the dynamic range is compressed between 0.5 and 1. Please make use of the full range, as some details might be missed because of this compression.

We are sorry for the incorrect unit of the spectrograms. We have provided the correct one with full range, please see below:

Author response image 4.

Author response image 5.

- The spectrogram in Figure 2D has several frequency chirps that do not seem physiological.

Thank you for your comments. The frequency chips of the spectrogram during the During and Post 1 phase were caused by recording noises. To avoid confusion, we have deleted the spectrogram in Figure 2D.

- The 3D plots in Figures 3G and H are not helpful. Thanks for the comment. We'd like to keep the 3D plots as they aid visual comparison of three different features of grooming, which complements other panels in Figure 3.

- The spectrograms in Figures 5A and B are too small, while the spectra in Figures 5C and D are too large. Please invert this relationship, as it is interesting and important to see the details in the spectrograms. The same happens in Figure 6.

We adjusted the layout of the Figure 5 and Figure 6 as requested, please see below:

Author response image 6.

Author response image 7.

- In Figure 6H, the authors compute the burst-suppression ratio during a period that seemingly has no bursts or suppressions (Figure 6B).

The burst-suppression ratio was computed from data with the minimum duration of burst and suppression periods set at 0.5 s. Sorry for the confusion. We added a new supplementary figure (Figure 6-figure supplement 8) displaying a 40-second EEG with a burst suppression period to better visualize the burst suppression.

Author response image 8.

- The data analyses are done in terms of p-values. They should be reported as confidence intervals so that any effect the authors wish to establish is measured along with its uncertainty.

Thank you for your valuable suggestions regarding our manuscript. We appreciate your thoughtful consideration of our work. We understand your concern but we would like to provide some justification for our choice of reporting p-values and explain why we believe they are appropriate for our study. First, the use of p-values for hypothesis testing and significance assessment is a common practice in our field. Many previous studies in our area of research also report results in terms of p-values. For example, Wei Xu11 published in 2020 suggested sevoflurane inhibits MPB neurons through postsynaptic GABAA-Rs and background potassium channels, Ao Y12 demonstrated that activation of the TH:LC-PVT projections is helpful in facilitating the transition from isoflurane anesthesia to an arousal state, using P-value as data analyses. By adhering to this convention, we ensure that our findings are consistent with the existing body of literature. This makes it easier for readers to compare and integrate our results with previous work. Secondly, while confidence intervals can provide a measure of effect size and uncertainty, p-values offer a concise way to communicate statistical significance. They help readers quickly assess whether an effect is statistically significant or not, which is often the primary concern when interpreting research findings. We hope that by providing these reasons for our choice of reporting p-values, we can address your concern while maintaining the integrity and consistency of our study. If you believe there are specific instances where reporting confidence intervals would be more informative, please feel free to highlight those, and we will consider your suggestion on a case-by-case basis.

References

- Baldini, G., Bagry, H. & Carli, F. Depth of anesthesia with desflurane does not influence the endocrine-metabolic response to pelvic surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 52, 99-105, doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2007.01470.x (2008).

- Niikura, R. et al. Exploratory analyses of postanesthetic effects of desflurane using behavioral test battery of mice. Behav Pharmacol 31, 597-609, doi:10.1097/fbp.0000000000000567 (2020).

- Marana, E. et al. Desflurane versus sevoflurane: a comparison on stress response. Minerva Anestesiol 79, 7-14 (2013).

- Vutskits, L. & Xie, Z. Lasting impact of general anaesthesia on the brain: mechanisms and relevance. Nat Rev Neurosci 17, 705-717, doi:10.1038/nrn.2016.128 (2016).

- Mashour, G. A. et al. Recovery of consciousness and cognition after general anesthesia in humans. Elife 10, doi:10.7554/eLife.59525 (2021).

- Mattison, M. L. P. Delirium. Ann Intern Med 173, Itc49-itc64, doi:10.7326/aitc202010060 (2020).

- Dahmani, S. et al. Pharmacological prevention of sevoflurane- and desflurane-related emergence agitation in children: a meta-analysis of published studies. Br J Anaesth 104, 216-223, doi:10.1093/bja/aep376 (2010).

- Lim, B. G. et al. Comparison of the incidence of emergence agitation and emergence times between desflurane and sevoflurane anesthesia in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 95, e4927, doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000004927 (2016).

- Radford, K. D. et al. Association between intravenous ketamine-induced stress hormone levels and long-term fear memory renewal in Sprague-Dawley rats. Behav Brain Res 378, 112259, doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112259 (2020).

- Yang, L., Chen, Z. & Xiang, D. Effects of intravenous anesthesia with sevoflurane combined with propofol on intraoperative hemodynamics, postoperative stress disorder and cognitive function in elderly patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery. Pak J Med Sci 38, 1938-1944, doi:10.12669/pjms.38.7.5763 (2022).

- Xu, W. et al. Sevoflurane depresses neurons in the medial parabrachial nucleus by potentiating postsynaptic GABA(A) receptors and background potassium channels. Neuropharmacology 181, 108249, doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2020.108249 (2020).

- Ao, Y. et al. Locus Coeruleus to Paraventricular Thalamus Projections Facilitate Emergence From Isoflurane Anesthesia in Mice. Front Pharmacol 12, 643172, doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.643172 (2021).

-

-

-

-

-

eLife assessment

This study presents potentially useful findings describing how activity in the corticotropin-releasing hormone neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus modulates sevoflurane anesthesia, as well as a phenomenon the authors term a "general anesthetic stress response". The technical approaches are solid and the data presented are largely clear. However, the primary conclusion, that the PVHCRH neurons are a mechanism of sevoflurane anesthesia, is inadequately supported.

-

Joint Public Review:

This study describes a group of CRH-releasing neurons, located in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, which, in mice, affects both the state of sevoflurane anesthesia and a grooming behavior observed after it. PVH-CRH neurons showed elevated calcium activity during the post-anesthesia period. Optogenetic activation of these PVH-CRH neurons during sevoflurane anesthesia shifts the EEG from burst-suppression to a seemingly activated state (an apparent arousal effect), although without a behavioral correlate. Chemogenetic activation of the PVH-CRH neurons delays sevoflurane-induced loss of righting reflex (another apparent arousal effect). On the other hand, chemogenetic inhibition of PVH-CRH neurons delays recovery of the righting reflex and decreases sevoflurane-induced stress (an apparent decrease in …

Joint Public Review:

This study describes a group of CRH-releasing neurons, located in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, which, in mice, affects both the state of sevoflurane anesthesia and a grooming behavior observed after it. PVH-CRH neurons showed elevated calcium activity during the post-anesthesia period. Optogenetic activation of these PVH-CRH neurons during sevoflurane anesthesia shifts the EEG from burst-suppression to a seemingly activated state (an apparent arousal effect), although without a behavioral correlate. Chemogenetic activation of the PVH-CRH neurons delays sevoflurane-induced loss of righting reflex (another apparent arousal effect). On the other hand, chemogenetic inhibition of PVH-CRH neurons delays recovery of the righting reflex and decreases sevoflurane-induced stress (an apparent decrease in the arousal effect). The authors conclude that PVH-CRH neurons are a common substrate for sevoflurane-induced anesthesia and stress. The PVH-CRH neurons are related to behavioral stress responses, and the authors claim that these findings provide direct evidence for a relationship between sevoflurane anesthesia and sevoflurane-mediated stress that might exist even when there is no surgical trauma, such as an incision. In its current form, the article does not achieve its intended goal.

Strengths

The manuscript uses targeted manipulation of the PVH-CRH neurons, and is technically sound. Also, the number of experiments is substantial.Weaknesses

The most significant weaknesses are a) the lack of consideration and measurement of GABAergic mechanisms of sevoflurane anesthesia, b) the failure to use another anesthetic as a control, c) a failure to document a compelling post-anesthesia stress response to sevoflurane in humans, d) limitations in the novelty of the findings. These weaknesses are related to the primary concerns described below:Concerns about the primary conclusion, that PVH-CRH neurons mediate "the anesthetic effects and post-anesthesia stress response of sevoflurane GA".