Autotrophic growth of Escherichia coli is achieved by a small number of genetic changes

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

eLife assessment

This is an important follow-up study to a previous paper in which the authors reconstituted CO2 metabolism (autotrophy) in Escherichia coli. Here, the authors define a set of just three mutations that promote autotrophy, highlighting the malleability of E. coli metabolism. The authors make a convincing case that mutations in pgi are loss-of-function mutations that prevent metabolic efflux from the reductive pentose phosphate autocatalytic cycle, and their data suggest possible roles of mutations in two other genes - crp and rpoB. This research will be particularly interesting to synthetic biologists, systems biologists, and metabolic engineers aiming to develop synthetic autotrophic microorganisms.

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

Synthetic autotrophy is a promising avenue to sustainable bioproduction from CO 2 . Here, we use iterative laboratory evolution to generate several distinct autotrophic strains. Utilising this genetic diversity, we identify that just three mutations are sufficient for Escherichia coli to grow autotrophically, when introduced alongside non-native energy (formate dehydrogenase) and carbon-fixing (RuBisCO, phosphoribulokinase, carbonic anhydrase) modules. The mutated genes are involved in glycolysis ( pgi ), central-carbon regulation ( crp ), and RNA transcription ( rpoB ). The pgi mutation reduces the enzyme’s activity, thereby stabilising the carbon-fixing cycle by capping a major branching flux. For the other two mutations, we observe down-regulation of several metabolic pathways and increased expression of native genes associated with the carbon-fixing module ( rpiB ) and the energy module ( fdoGH ), as well as an increased ratio of NADH/NAD + - the cycle’s electron-donor. This study demonstrates the malleability of metabolism and its capacity to switch trophic modes using only a small number of genetic changes and could facilitate transforming other heterotrophic organisms into autotrophs.

Article activity feed

-

-

-

-

Author Response

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

Recommendations for the authors:

The single-mutant and double-mutant crp/rpoB strains were made by co-transduction with a nearby gene deletion (kanR-marked). I couldn't tell from the methods section whether these mutants, e.g., crp-H22N delta-chiA, were compared to wild-type cells or deletion mutants, e.g., delta chiA, in the proteomics experiments. I encourage the authors to explain this more clearly in the methods section, and to briefly mention in the Results section and relevant figure legends that the crp/rpoB mutant strains (and possibly the "wild-type" strains) also have gene deletions. If the comparison "wild-type" strains are fully wild-type (i.e., not deleted for chiA/yjaH), it is especially important to mention this in the Results section and …

Author Response

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

Recommendations for the authors:

The single-mutant and double-mutant crp/rpoB strains were made by co-transduction with a nearby gene deletion (kanR-marked). I couldn't tell from the methods section whether these mutants, e.g., crp-H22N delta-chiA, were compared to wild-type cells or deletion mutants, e.g., delta chiA, in the proteomics experiments. I encourage the authors to explain this more clearly in the methods section, and to briefly mention in the Results section and relevant figure legends that the crp/rpoB mutant strains (and possibly the "wild-type" strains) also have gene deletions. If the comparison "wild-type" strains are fully wild-type (i.e., not deleted for chiA/yjaH), it is especially important to mention this in the Results section and the figure legends since the phenotypic changes could be due to the gene deletions rather than the mutations in crp/rpoB

We appreciate and agree with the editor's suggestion to clarify this point.

Accordingly, we have made the following changes to the text:

p11 L30-34 in the main text:

"The second experiment similarly compared an engineered BW25113 (BW) strain, containing the two regulatory mutations from the compact set (i.e., crp H22N and rpoB A1245V) together with the deletions used to insert them (see methods and DataS1 file), to a “wild type” BW strain (a corresponding knockout strain without the mutations, see methods)."

p28 under Chemostat proteomics experiment L13-16 in methods:

"The starting volume of each bioreactor was 150 ml M9 media supplemented with either 30 mM and 10mM D-xylose for the evolved and ancestor samples or only 10mM D-xylose for BW including compact set mutations and/or the deletions used for their insertions (DataS1 file). The minimal media also included trace elements and vitamin B1 was omitted."

-

eLife assessment

This is an important follow-up study to a previous paper in which the authors reconstituted CO2 metabolism (autotrophy) in Escherichia coli. Here, the authors define a set of just three mutations that promote autotrophy, highlighting the malleability of E. coli metabolism. The authors make a convincing case that mutations in pgi are loss-of-function mutations that prevent metabolic efflux from the reductive pentose phosphate autocatalytic cycle, and their data suggest possible roles of mutations in two other genes - crp and rpoB. This research will be particularly interesting to synthetic biologists, systems biologists, and metabolic engineers aiming to develop synthetic autotrophic microorganisms.

-

Joint Public Review:

The authors previously showed that expressing formate dehydrogenase, rubisco, carbonic anhydrase, and phosphoribulokinase in Escherichia coli, followed by experimental evolution, led to the generation of strains that can metabolise CO2. Using two rounds of experimental evolution, the authors identify mutations in three genes - pgi, rpoB, and crp - that allow cells to metabolise CO2 in their engineered strain background. The authors make a strong case that mutations in pgi are loss-of-function mutations that prevent metabolic efflux from the reductive pentose phosphate autocatalytic cycle. The authors also use proteomic analysis to probe the role of the mutations in crp and rpoB. While they do not reach strong conclusions about how these mutations promote autotrophic growth, they provide some clues, leading to …

Joint Public Review:

The authors previously showed that expressing formate dehydrogenase, rubisco, carbonic anhydrase, and phosphoribulokinase in Escherichia coli, followed by experimental evolution, led to the generation of strains that can metabolise CO2. Using two rounds of experimental evolution, the authors identify mutations in three genes - pgi, rpoB, and crp - that allow cells to metabolise CO2 in their engineered strain background. The authors make a strong case that mutations in pgi are loss-of-function mutations that prevent metabolic efflux from the reductive pentose phosphate autocatalytic cycle. The authors also use proteomic analysis to probe the role of the mutations in crp and rpoB. While they do not reach strong conclusions about how these mutations promote autotrophic growth, they provide some clues, leading to valuable speculation.

Comments on revised version:

The authors have thoroughly addressed the reviewers' comments. The major addition to the paper is the proteomic analysis of single and double mutants of crp and rpoB. These new data provide clues as to the role of the crp and rpoB mutations in promoting autotrophic growth, which the authors discuss. The authors acknowledge that it will require additional experiments to determine whether the speculated mechanisms are correct. Nonetheless, the new data provide valuable new insight into the role of the crp and rpoB mutations. The authors have also expanded their description of the crp and rpoB mutations, making it clearer that the effects of these mutations are likely to be distinct, albeit with potential for overlap in function. -

-

Author Response

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Author response:

Reviewer #1:

The main objective of this study is to achieve the development of a synthetic autotroph using adaptive laboratory evolution. To accomplish this, the authors conducted chemostat cultivation of engineered E. coli strains under xylose-limiting conditions and identified autotrophic growth and the causative mutations. Additionally, the mutational mechanisms underlying these causative mutations were also explored with drill down assays. Overall, the authors demonstrated that only a small number of genetic changes were sufficient (i.e., 3) to construct an autotrophic E. coli when additional heterologous genes were added. While natural autotrophic microorganisms typically exhibit low genetic tractability, numerous studies have …

Author Response

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Author response:

Reviewer #1:

The main objective of this study is to achieve the development of a synthetic autotroph using adaptive laboratory evolution. To accomplish this, the authors conducted chemostat cultivation of engineered E. coli strains under xylose-limiting conditions and identified autotrophic growth and the causative mutations. Additionally, the mutational mechanisms underlying these causative mutations were also explored with drill down assays. Overall, the authors demonstrated that only a small number of genetic changes were sufficient (i.e., 3) to construct an autotrophic E. coli when additional heterologous genes were added. While natural autotrophic microorganisms typically exhibit low genetic tractability, numerous studies have focused on constructing synthetic autotrophs using platform microorganisms such as E. coli. Consequently, this research will be of interest to synthetic biologists and systems biologists working on the development of synthetic autotrophic microorganisms. The conclusions of this paper are mostly well supported by appropriate experimental methods and logical reasoning. However, further experimental validation of the mutational mechanisms involving rpoB and crp would enhance readers' understanding and provide clearer insights, despite acknowledgement that these genes impact a broad set of additional genes. Additionally, a similar study, 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001186, where pgi was deleted from the E. coli genome and evolved to reveal an rpoB mutation is relevant to this work and should be placed in the context of the presented findings.

We thank the reviewer for pointing this study out. It is very interesting that a mutation in a similar region in RpoB was observed in a related context of Pgi loss of activity. We have added a reference to this study in our text (Page 11, line 21).

he authors addressed rpoB and crp as one unit and performed validation. They cultivated the mutant strain and wild type in a minimal xylose medium with or without formate, comparing their growth and NADH levels. The authors argued that the increased NADH level in the mutant strain might facilitate autotrophic growth. Although these phenotypes appear to be closely related, their relationship cannot be definitively concluded based on the findings presented in this paper alone. Therefore, one recommendation is to explore investigating transcriptomic changes induced by the rpoB and crp mutations. Otherwise, conducting experimental verification to determine whether the NADH level directly causes autotrophic growth would provide further support for the authors' claim.

We appreciate the valuable comment and agree that the work was lacking such an analysis. Due to various reasons we have opted to use a proteomic approach which we feel fulfills the same purpose as the transcriptomics suggestion. We found interesting evidence in up-regulation of the fdoGH operon (comprising the native formate dehydrogenase O enzyme complex) which could indicate why there is an increase in NADH/NAD+ levels. We also hypothesize that this upregulation might be important more generally by drawing comparisons to natural chemo-autotrophs.

Further experimental work (which we were not able to include in the current study) could help validate this link by deleting fdoGH and observing a loss of phenotype and, on the flip side, directly overexpressing the fdoGH operon and observing an increase in the NADH/NAD+ ratio. Indeed, if this overexpression were to prove sufficient for achieving an autotrophic phenotype without the mutations in the global transcription regulators, it would be a much more transparent design.

We have added a section titled "Proteomic analysis reveals up-regulation of rPP cycle and formate-associated genes alongside down-regulation of catabolic genes" to the Results based on this analysis.

- It would be beneficial to provide a more detailed explanation of the genetic background before the evolution stage, specifically regarding the ∆pfk and ∆zwf mutations. Furthermore, it is suggested to include a figure that provides a comprehensive depiction of the reductive pentose phosphate pathway and the bypass pathway. These will help readers grasp the concept of the "metabolic scaffold" as proposed by the authors.

We agree with the reviewer that this could be helpful and we added a reference to the original paper Gleizer et al. 2019 that reported this design and also includes the relevant figure. We feel that the figure should not be added to the current manuscript as we continue to show that this design is not relevant in the context of the three reported mutations and such a figure could distract the attention of the reader from the main takeaways of the current study.

- Despite the essentiality of the rpoB mutation (A1245V) to the autotrophic phenotype in the final strain, the inclusion of this mutation in step C1 does not appear to be justified. According to line 37 on page 3, the authors chose to retain the unintended mutation in rpoB based on its essentiality to the phenotype observed in other evolved strains. However, it should be noted that the mutations found in the evolved strain I, II, and III (P552T or D866E) were entirely different from the unintended mutation (A1245V) during genetic engineering. This aspect should be revised to avoid confusion among readers.

Thank you for pointing this issue out, we added a clarification in the text (page 4 line 7) to avoid such confusion. We believe this point is much clearer now.

The rpoB mutation which was shown to be essential in the study is indeed known to be common in ALE experiments in E. coli. Thus, I searched the different rpoB mutations in ALEdb in E. coli and I was able to find a similar mutation in a study where pgi was knocked out and then evolved. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1001186 This study seems very relevant given that pgi was a key mutation in the compact set of this work and the section "Modulation of a metabolic branch-point activity increased the concentration of rPP metabolites" informs that loss of function mutations in pgi were also found. The findings of this study should thus be put in the context of the previous related ALE study. I would recommend a similar analysis of crp mutations from studies in ALEdb to see if there are similar mutations in this gene as well or if this a unique mutation.

We thank the reviewer for bringing this publication to our attention. We have addressed this observation in the main text (page 11 , line 21). We agree that it could have some connection to the pgi mutation yet we would not want to overspeculate about this role, as we also found the exact same mutation (A1245V) as an adaptation to higher temperature in another E. coli study (Tenaillon et al. 2012). We would like to bring forward the fact that the two reported rpoB mutations are always accompanied by another mutation with pleiotropic effects, either in the transcription factor Crp or in another RNA polymerase subunit (e.g RpoC). As such many epistatic effects could occur, one of which we also report here in page 13, line 18. In conclusion, although there could be a connection between the rpoB and pgi mutations, it could be a mere coincidence and the two mutations could exhibit two distinct roles in two distinct phenotypes.

We also would like to thank the reviewer for suggesting a similar analysis for crp and found another mutation at a nearby residue with strong adaptive effects and mentioned it in our main text.

Can the typical number of mutations found in a given ALE experiment be directly compared to those found in this study? It seems like a retrospective analysis of other ALE studies to show how many mutations typically occur in an ALE study and sets which were found to be causal to reproduce the phenotype of interest (through similar reverse engineering in the starting strain) should be presented. Again, the authors cite ALEdb which should provide direct numbers of mutations found in similar ALE studies with E. coli and one could then examine them to find sets of clearly causal mutations which recreate phenotypes of interest. Such an analysis would go a long way in supporting the main finding of "small number" of mutations.

Discussion, page 12, line 42. "This could serve as a promising strategy for achieving minimally perturbed genotypes in future metabolic engineering attempts". There is an entire body of work around growth-coupled production which can be predicted and evolved with a genome-scale metabolic model and ALE. Thus, if this statement is going to be made, relevant studies should be cited and placed in context.

The reviewer raises an important point which could indeed yield an interesting perspective. However, it would be difficult to perform this comparison in practice since many of the studies published on ALEdb have not isolated essential mutations from other mutation incidents nor have they determined the role of each mutation in the reported phenotypes. For example, many ALE trajectories include a hypermutator that greatly increases the number of irrelevant mutations and it is nearly impossible to sieve through them to find an essential set.

Moreover, it is hard to compare the “level of difficulty” of achieving one phenotype over another and therefore feel that even though such an analysis would be insightful, it requires an amount of work which is outside the scope of this study.

Finally, we would like to highlight our approach of using the iterative approach, isolating the relevant consensus mutations and repeating this process until no evolution process is required, we are not aware of prior studies that used this approach.

We now clarified what we mean by "promising strategy" in the discussion in order to avoid any false claims about novelty (page 16 line 32): "Using metabolic growth-coupling as a temporary 'metabolic scaffold' that can be removed, could serve as a promising strategy for achieving minimally perturbed genotypes in future metabolic engineering attempts."

Reviewer #2:

Synthetic autotrophy of biotechnologically relevant microorganisms offers exciting chances for CO2 neutral or even CO2 negative production of goods. The authors' lab has recently published an engineered and evolved Escherichia coli strain that can grow on CO2 as its only carbon source. Lab evolution was necessary to achieve growth. Evolved strains displayed tens of mutations, of which likely not all are necessary for the desired phenotype.

In the present paper the authors identify the mutations that are necessary and sufficient to enable autotrophic growth of engineered E. coli. Three mutations were identified, and their phenotypic role in enhancing growth via the introduced Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle were characterized. It was demonstrated that these mutations allow autotrophic growth of E. coli with the introduced CBB cycle without any further metabolic intervention. Autotrophic growth is demonstrated by 13C labelling with 13C CO2, measured in proteinogenic amino acids. In Figures 2B and S1, the labeling data are shown, with an interval of the "predicted range under 13CO2".

Here, the authors should describe how this interval was derived.

The methodology is clearly described and appropriate.

The present results will allow other labs to engineer E. coli and other microorganisms further to assimilate CO2 efficiently into biomass and metabolic products. The importance is evident in the opportunity to employ such strain in CO2 based biotech processes for the production of food and feed protein or chemicals, to reduce atmospheric CO2 levels and the consumption of fossil resources.

Please describe in the methodology how the interval of the predicted range of 13C labeling was derived for Figures 2B and S1. Was it calculated by the dilution factor during 4 generations, or did you predict the label incorporation individually with a metabolic model?

The text needs careful editing, some sentences are incomplete and there are frequent inconsistencies in writing metabolites and enzymes.

P2L6: unclear sentence (incomplete?)

P2L19: pastoris with lower case "p"

P2L40: incomplete sentence

P2L42: here, and at many other places, the writing of RuBisCO needs to be aligned. It is an abbreviation and should begin with a capital letter. Most commonly it is written as RuBisCO which I would suggest - please unify throughout the text.

P3L3: formate dehydrogenase ... metabolites and enzymes with lower case letter. And, no hyphen here.

P5L4: delete the : after unintentionally

P6L16: carboxylation of RuBP (it is not CO2 that is carboxylated - if any, CO2 is carboxylating)

P7L25: phosphoglucoisomerase (lower case)

P8L5: in line

P8L9: part of glycolysis/ ...

P10L4: pentose phosphates (lower case, no hyphen).

P10L4: all metabolites lower case

P12L28: incomplete sentence

P18L4: Escherichia coli in italics P18L15: Pseudomonas sp. in italics P18L16: ... promoter and with a strong ...

P20, chapter Metabolomics: put the numbers of 12C and 13C in superscript P23L9: pentose phosphates ; all metabolites in lower case (as above) P23: all 12C and 13C with superscript numbers.

Response to reviewer #2:

We thank the reviewer for their comments, and for pointing out the need to clarify how we derived the predicted range of 13C labeling. We edited the text accordingly, and added the relevant calculation to the methods section (under the “13C Isotopic labeling experiment”). We would like to also thank the reviewer for the required text improvements, which were implemented.

Reviewer #3:

The authors previously showed that expressing formate dehydrogenase, rubisco, carbonic anhydrase, and phosphoribulokinase in Escherichia coli, followed by experimental evolution, led to the generation of strains that can metabolise CO2. Using two rounds of experimental evolution, the authors identify mutations in three genes - pgi, rpoB, and crp - that allow cells to metabolise CO2 in their engineered strain background. The authors make a strong case that mutations in pgi are loss-of-function mutations that prevent metabolic efflux from the reductive pentose phosphate autocatalytic cycle. The authors also argue that mutations in crp and rpoB lead to an increase in the NADH/NAD+ ratio, which would increase the concentration of the electron donor for carbon fixation. While this may explain the role of the crp and rpoB mutations, there is good reason to think that the two mutations have independent effects, and that the change in NADH/NAD+ ratio may not be the major reason for their importance in the CO2-metabolising strain.

We thank the reviewer for their comments and constructive feedback.

We agree that there is probably a broader effect caused by the rpoB and crp mutations, besides the change in the NADH/NAD+ ratio. Hence, we performed a proteomics analysis, comparing the rpoB and crp mutations on a WT background to an autotrophic E.coli, searching for a mutual change in both strains compared to their "ancestors". We found up-regulation of rPP cycle and formate-associated genes, and a down-regulation of catabolic genes. We added a section dedicated to this matter under the title "Proteomic analysis reveals up-regulation of rPP cycle and formate-associated genes alongside down-regulation of catabolic genes".

Specific comments:

- Deleting pgi rather than using a point mutation would allow the authors to more rigorously test whether loss-off-function mutants are being selected for in their experimental evolution pipeline. The same argument applies to crp.

We appreciate this recommendation and indeed tried to delete pgi, but the genetic manipulation caused a knockout of other genes along with pgi (pepE, rluF, yjbD, lysC) so in the time available to us we cannot confidently determine whether the deletion alone is sufficient and can replace the mutation.

Regarding crp, we do not think there is a reason to believe the mutation is a loss-of-function. In any case, the proteomics-based characterization of the crp mutation is now included in the SI.

- Page 10, lines 10-11, the authors state "Since Crp and RpoB are known to physically interact in the cell (26-28), we address them as one unit, as it is hard to decouple the effect of one from the other". CRP and RpoB are connected, but the authors' description of them is misleading. CRP activates transcription by interacting with RNA polymerase holoenzyme, of which the Beta subunit (encoded by rpoB) is a part. The specific interaction of CRP is with a different RNA polymerase subunit. The functions of CRP and RpoB, while both related to transcription, are otherwise very different. The mutations in crp and rpoB are unlikely to be directly functionally connected. Hence, they should be considered separately.

Indeed, the fact that the proteins are interacting in the cell does not necessarily mean that the mutations are functionally connected. We therefore added as further justification in the new section:

"As far as we know, the mutations in the Crp and RpoB genes affect the binding of the RNA polymerase complex to DNA and/or its transcription rates. Depending on the transcribed gene target, the effect of the two mutations might be additive, antagonistic, or synergistic. Since each one of these mutations individually (in combination with the pgi mutation) is not sufficient to achieve autotrophic growth, it is reasonable to assume that only the target genes whose levels of expression change significantly in the double-mutant are the ones relevant for the autotrophic phenotype”.

In our proteomics analysis we considered each mutation separately. We found that in some cases the two mutations together have an additive effect, but in other cases we found that the two mutations together affect differently on the proteome, compared to the effect of each mutation alone. Since both mutations are essential to the phenotype, we decided to go with the approach of addressing the two mutations as one unit for the physiological and metabolic experiments.

- A Beta-galactosidase assay would provide a very simple test of CRP H22N activity. There are also simple in vivo and in vitro assays for transcription activation (two different modes of activation) and DNA-binding. H22 is not near the DNA-binding domain, but may impact overall protein structure.

The mutation is located in “Activating Region 2”, interacting with RNA polymerase. We tried an in-vivo assay to determine the CRP H22N activity and got inconclusive results, we believe the proteomics analysis serves as a good method for understanding the global effect of the mutation.

- There are many high-resolution structures of both CRP and RpoB (in the context of RNA polymerase). The authors should compare the position of the sites of mutation of these proteins to known functional regions, assuming H22N is not a loss-of-function mutation in crp.

We added a supplementary figure regarding the structural location of the two mutations, where it is demonstrated that crp H22N is located in a region interacting with the RNA polymerase and rpoB A1245V is located in proximity to regions interacting with the DNA.

- RNA-seq would provide a simple assay for the effects of the crp and rpoB mutations. While the precise effect of the rpoB mutation on RNA polymerase function may be hard to discern, the overall impact on gene expression would likely be informative.

Indeed we agree that an omics approach to infer the global effect of these mutations is beneficial, we opted to use a proteomics approach and think it serves the purpose of clarifying the final, down-stream, effect on the cell.

- Page 2, lines 40-45, the authors should more clearly explain that the deletion of pfkA, pfkB and zwf was part of the experimental evolution strategy in their earlier work (Gleizer et al., 2019), and not a new strategy in the current study.

We thank you for pointing this out, and edited the text accordingly.

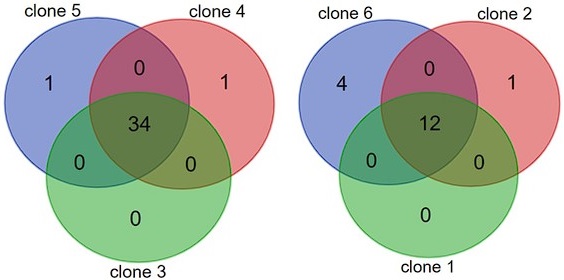

- Page 3, line 27. Why did the authors compare the newly acquired mutants to only two mutants from the earlier work, not all 6?

The 6 clones that were isolated in Gleizer et al., had 2 distinct mutation profiles. During the isolation process the lineage split into two groups. Three out of the 6 clones (clones 1,2,6) came from the same ancestor, and the other three (clones 3,4,5) came from another ancestor. Hence, these two groups shared almost all of their mutations (see Venn diagram). We decided to use for our comparison the representative with the highest number of mutations from each group (clones 5 and 6).

Author response image 1.

-

eLife assessment

This is an important follow-up study to a previous paper in which the authors reconstituted CO2 metabolism (autotrophy) in Escherichia coli. Here, the authors define a set of just three mutations that promote autotrophy, highlighting the malleability of E. coli metabolism. The authors make a convincing case that mutations in pgi are loss-of-function mutations that prevent metabolic efflux from the reductive pentose phosphate autocatalytic cycle, and their data suggest possible roles of mutations in two other genes - crp and rpoB. This research will be particularly interesting to synthetic biologists, systems biologists, and metabolic engineers aiming to develop synthetic autotrophic microorganisms.

-

Joint Public Review:

The authors previously showed that expressing formate dehydrogenase, rubisco, carbonic anhydrase, and phosphoribulokinase in Escherichia coli, followed by experimental evolution, led to the generation of strains that can metabolise CO2. Using two rounds of experimental evolution, the authors identify mutations in three genes - pgi, rpoB, and crp - that allow cells to metabolise CO2 in their engineered strain background. The authors make a strong case that mutations in pgi are loss-of-function mutations that prevent metabolic efflux from the reductive pentose phosphate autocatalytic cycle. The authors also use proteomic analysis to probe the role of the mutations in crp and rpoB. While they do not reach strong conclusions about how these mutations promote autotrophic growth, they provide some clues, leading to …

Joint Public Review:

The authors previously showed that expressing formate dehydrogenase, rubisco, carbonic anhydrase, and phosphoribulokinase in Escherichia coli, followed by experimental evolution, led to the generation of strains that can metabolise CO2. Using two rounds of experimental evolution, the authors identify mutations in three genes - pgi, rpoB, and crp - that allow cells to metabolise CO2 in their engineered strain background. The authors make a strong case that mutations in pgi are loss-of-function mutations that prevent metabolic efflux from the reductive pentose phosphate autocatalytic cycle. The authors also use proteomic analysis to probe the role of the mutations in crp and rpoB. While they do not reach strong conclusions about how these mutations promote autotrophic growth, they provide some clues, leading to valuable speculation.

Comments on revised version:

The authors have thoroughly addressed the reviewers' comments. The major addition to the paper is the proteomic analysis of single and double mutants of crp and rpoB. These new data provide clues as to the role of the crp and rpoB mutations in promoting autotrophic growth, which the authors discuss. The authors acknowledge that it will require additional experiments to determine whether the speculated mechanisms are correct. Nonetheless, the new data provide valuable new insight into the role of the crp and rpoB mutations. The authors have also expanded their description of the crp and rpoB mutations, making it clearer that the effects of these mutations are likely to be distinct, albeit with potential for overlap in function.

-

-

eLife assessment

This is an important follow-up study to a previous paper in which the authors reconstituted CO2 metabolism in Escherichia coli (autotrophy). Here, the authors define a set of three mutations that promote autotrophy, highlighting the malleability of E. coli metabolism. The authors make a convincing case that mutations in pgi are loss-of-function mutations that prevent metabolic efflux from the reductive pentose phosphate autocatalytic cycle, but claims about the role of mutations in two other genes - crp and rpoB - are currently incomplete. This research will be particularly interesting to synthetic biologists, systems biologists, and metabolic engineers aiming to develop synthetic autotrophic microorganisms.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The main objective of this study is to achieve the development of a synthetic autotroph using adaptive laboratory evolution. To accomplish this, the authors conducted chemostat cultivation of engineered E. coli strains under xylose-limiting conditions and identified autotrophic growth and the causative mutations. Additionally, the mutational mechanisms underlying these causative mutations were also explored with drill down assays. Overall, the authors demonstrated that only a small number of genetic changes were sufficient (i.e., 3) to construct an autotrophic E. coli when additional heterologous genes were added. While natural autotrophic microorganisms typically exhibit low genetic tractability, numerous studies have focused on constructing synthetic autotrophs using platform microorganisms such as E. …

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The main objective of this study is to achieve the development of a synthetic autotroph using adaptive laboratory evolution. To accomplish this, the authors conducted chemostat cultivation of engineered E. coli strains under xylose-limiting conditions and identified autotrophic growth and the causative mutations. Additionally, the mutational mechanisms underlying these causative mutations were also explored with drill down assays. Overall, the authors demonstrated that only a small number of genetic changes were sufficient (i.e., 3) to construct an autotrophic E. coli when additional heterologous genes were added. While natural autotrophic microorganisms typically exhibit low genetic tractability, numerous studies have focused on constructing synthetic autotrophs using platform microorganisms such as E. coli. Consequently, this research will be of interest to synthetic biologists and systems biologists working on the development of synthetic autotrophic microorganisms. The conclusions of this paper are mostly well supported by appropriate experimental methods and logical reasoning. However, further experimental validation of the mutational mechanisms involving rpoB and crp would enhance readers' understanding and provide clearer insights, despite acknowledgement that these genes impact a broad set of additional genes. Additionally, a similar study, 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001186, where pgi was deleted from the E. coli genome and evolved to reveal an rpoB mutation is relevant to this work and should be placed in the context of the presented findings.

The authors addressed rpoB and crp as one unit and performed validation. They cultivated the mutant strain and wild type in a minimal xylose medium with or without formate, comparing their growth and NADH levels. The authors argued that the increased NADH level in the mutant strain might facilitate autotrophic growth. Although these phenotypes appear to be closely related, their relationship cannot be definitively concluded based on the findings presented in this paper alone. Therefore, one recommendation is to explore investigating transcriptomic changes induced by the rpoB and crp mutations. Otherwise, conducting experimental verification to determine whether the NADH level directly causes autotrophic growth would provide further support for the authors' claim.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Synthetic autotrophy of biotechnologically relevant microorganisms offers exciting chances for CO2 neutral or even CO2 negative production of goods. The authors' lab has recently published an engineered and evolved Escherichia coli strain that can grow on CO2 as its only carbon source. Lab evolution was necessary to achieve growth. Evolved strains displayed tens of mutations, of which likely not all are necessary for the desired phenotype.

In the present paper the authors identify the mutations that are necessary and sufficient to enable autotrophic growth of engineered E. coli. Three mutations were identified, and their phenotypic role in enhancing growth via the introduced Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle were characterized. It was demonstrated that these mutations allow autotrophic growth of E. coli with the …

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Synthetic autotrophy of biotechnologically relevant microorganisms offers exciting chances for CO2 neutral or even CO2 negative production of goods. The authors' lab has recently published an engineered and evolved Escherichia coli strain that can grow on CO2 as its only carbon source. Lab evolution was necessary to achieve growth. Evolved strains displayed tens of mutations, of which likely not all are necessary for the desired phenotype.

In the present paper the authors identify the mutations that are necessary and sufficient to enable autotrophic growth of engineered E. coli. Three mutations were identified, and their phenotypic role in enhancing growth via the introduced Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle were characterized. It was demonstrated that these mutations allow autotrophic growth of E. coli with the introduced CBB cycle without any further metabolic intervention. Autotrophic growth is demonstrated by 13C labelling with 13C CO2, measured in proteinogenic amino acids. In Figures 2B and S1, the labeling data are shown, with an interval of the "predicted range under 13CO2". Here, the authors should describe how this interval was derived.

The methodology is clearly described and appropriate.

The present results will allow other labs to engineer E. coli and other microorganisms further to assimilate CO2 efficiently into biomass and metabolic products. The importance is evident in the opportunity to employ such strain in CO2 based biotech processes for the production of food and feed protein or chemicals, to reduce atmospheric CO2 levels and the consumption of fossil resources.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

The authors previously showed that expressing formate dehydrogenase, rubisco, carbonic anhydrase, and phosphoribulokinase in Escherichia coli, followed by experimental evolution, led to the generation of strains that can metabolise CO2. Using two rounds of experimental evolution, the authors identify mutations in three genes - pgi, rpoB, and crp - that allow cells to metabolise CO2 in their engineered strain background. The authors make a strong case that mutations in pgi are loss-of-function mutations that prevent metabolic efflux from the reductive pentose phosphate autocatalytic cycle. The authors also argue that mutations in crp and rpoB lead to an increase in the NADH/NAD+ ratio, which would increase the concentration of the electron donor for carbon fixation. While this may explain the role of the crp …

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

The authors previously showed that expressing formate dehydrogenase, rubisco, carbonic anhydrase, and phosphoribulokinase in Escherichia coli, followed by experimental evolution, led to the generation of strains that can metabolise CO2. Using two rounds of experimental evolution, the authors identify mutations in three genes - pgi, rpoB, and crp - that allow cells to metabolise CO2 in their engineered strain background. The authors make a strong case that mutations in pgi are loss-of-function mutations that prevent metabolic efflux from the reductive pentose phosphate autocatalytic cycle. The authors also argue that mutations in crp and rpoB lead to an increase in the NADH/NAD+ ratio, which would increase the concentration of the electron donor for carbon fixation. While this may explain the role of the crp and rpoB mutations, there is good reason to think that the two mutations have independent effects, and that the change in NADH/NAD+ ratio may not be the major reason for their importance in the CO2-metabolising strain.

Specific comments:

1. Deleting pgi rather than using a point mutation would allow the authors to more rigorously test whether loss-off-function mutants are being selected for in their experimental evolution pipeline. The same argument applies to crp.

2. Page 10, lines 10-11, the authors state "Since Crp and RpoB are known to physically interact in the cell (26-28), we address them as one unit, as it is hard to decouple the effect of one from the other". CRP and RpoB are connected, but the authors' description of them is misleading. CRP activates transcription by interacting with RNA polymerase holoenzyme, of which the Beta subunit (encoded by rpoB) is a part. The specific interaction of CRP is with a different RNA polymerase subunit. The functions of CRP and RpoB, while both related to transcription, are otherwise very different. The mutations in crp and rpoB are unlikely to be directly functionally connected. Hence, they should be considered separately.

3. A Beta-galactosidase assay would provide a very simple test of CRP H22N activity. There are also simple in vivo and in vitro assays for transcription activation (two different modes of activation) and DNA-binding. H22 is not near the DNA-binding domain, but may impact overall protein structure.

4. There are many high-resolution structures of both CRP and RpoB (in the context of RNA polymerase). The authors should compare the position of the sites of mutation of these proteins to known functional regions, assuming H22N is not a loss-of-function mutation in crp.

5. RNA-seq would provide a simple assay for the effects of the crp and rpoB mutations. While the precise effect of the rpoB mutation on RNA polymerase function may be hard to discern, the overall impact on gene expression would likely be informative.

-