A Pvr–AP-1–Mmp1 signaling pathway is activated in astrocytes upon traumatic brain injury

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

eLife assessment

This study represents a valuable finding on the neuron-glia communication and glial responses to traumatic brain injury (TBI). The data supporting the authors' conclusions on TBI analysis, RNA-seq on FACS sorted astrocytes, genetic analyses on Pvr-JNK/MMP1 are solid. However, cellular aspects of the response to TBI, statistical analysis, and molecular links between Pvr-AP1 are incomplete, which could be further strengthened in the future by more rigorous analyses.

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) caused by external mechanical forces is a major health burden worldwide, but the underlying mechanism in glia remains largely unclear. We report herein that Drosophila adults exhibit a defective blood–brain barrier, elevated innate immune responses, and astrocyte swelling upon consecutive strikes with a high-impact trauma device. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis of these astrocytes revealed upregulated expression of genes encoding PDGF and VEGF receptor-related (Pvr, a receptor tyrosine kinase), adaptor protein complex 1 (AP-1 , a transcription factor complex of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway) composed of Jun-related antigen (Jra) and kayak (kay), and matrix metalloproteinase 1 (Mmp1) following TBI. Interestingly, Pvr is both required and sufficient for AP-1 and Mmp1 upregulation, while knockdown of AP-1 expression in the background of Pvr overexpression in astrocytes rescued Mmp1 upregulation upon TBI, indicating that Pvr acts as the upstream receptor for the downstream AP-1–Mmp1 transduction. Moreover, dynamin-associated endocytosis was found to be an important regulatory step in downregulating Pvr signaling. Our results identify a new Pvr–AP-1–Mmp1 signaling pathway in astrocytes in response to TBI, providing potential targets for developing new therapeutic strategies for TBI.

Article activity feed

-

-

-

Author Response

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations For The Authors):

To resolve and further test the claim that TBI did not induce cell proliferation:

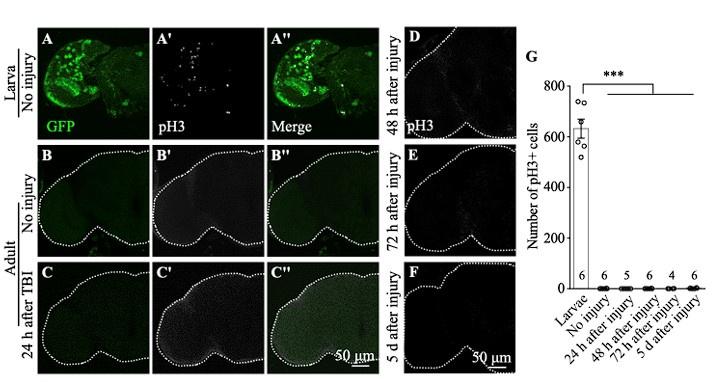

How many brains did they analyse? Sample sizes must be provided in Figure S1.

As per reviewer’s suggestion, we removed one of the unsupported claims shown in Figure S1. The original Figure S1 is shown below with the sample number added.

Author response image 1.

The authors could either improve the TBI method or the detection of cells in S-phase, mitosis or cycling. They could use PCNA-GFP or BrdU, EdU or FUCCI instead and at least provide evidence that they can detect cells in S-phase in intact brains. Timing is critical (ie cell cycle is longer than in larvae) so multiple time points …

Author Response

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations For The Authors):

To resolve and further test the claim that TBI did not induce cell proliferation:

How many brains did they analyse? Sample sizes must be provided in Figure S1.

As per reviewer’s suggestion, we removed one of the unsupported claims shown in Figure S1. The original Figure S1 is shown below with the sample number added.

Author response image 1.

The authors could either improve the TBI method or the detection of cells in S-phase, mitosis or cycling. They could use PCNA-GFP or BrdU, EdU or FUCCI instead and at least provide evidence that they can detect cells in S-phase in intact brains. Timing is critical (ie cell cycle is longer than in larvae) so multiple time points should be tested. Or they could use pH3 but test more time points and rather large sample sizes. If they are not able to provide any evidence, then their lack of evidence is no evidence. The authors should consider removing pH3 and PCNA-GFP related claims instead.

We have removed pH3 and PCNA-GFP related results and claims.

Other unsupported claims:

Figure 2A-C is not very clear what they are showing, but it is not evidence of astrocyte hypertrophy. It does not have cellular resolution and does not show the cell size, membranes, nor number

(1) We have avoided the term “hypertrophy” and changed the description throughout the text to “astrocyte swelling”.

(2) Images in the resolution of Figure 2E and 2F were able to show the enlarged soma of astrocytes, suggesting swelling.

What is the point of using RedStinger in Figure 2?

We used RedStinger to label the astrocyte nuclei.

Figure S5 is not convincing, as anti-Pvr does not look localised to specific cells. Instead, it looks like uniform background. If they really think the antibody is localised, they should do double stainings with cell type specific markers. If the antibody does not work, then remove the data and the claim. They could test with RNAi knock-down in specific cell types and qRT-PCR which cells express pvr instead.

We have removed the claim that “Pvr is predominantly expressed in astrocytes” and changed the description to “Immunostainings using the anti-Pvr antibodies revealed that endogenous Pvr expression is low in the control brains, yet significantly enhanced upon TBI. Reducing Pvr expression, but not Pvr overexpression, in astrocytes blocked the TBI-induced increase of Pvr expression (Figure S5)”.

Figure S6: it is unclear what they are trying to show, but these data do not demonstrate that astrocytes do not engulf debris after TBI, as there isn't sufficient cellular resolution to make such claim. Firstly, they analyse one single cell per treatment. Secondly, the cell projections are not visible in these images, and therefore engulfment cannot be seen. The authors could remove the claim or visualise whether astrocytes phagocytose debris or not either using clones or with TEM.

We agree with the reviewer that our images do not have the resolution to make this claim. We have removed Figure S6 and corresponding text description.

On statistics:

The statistical analysis needs revising as it is wrong in multiple places, eg Fig.1F,G,H; Figure 2D. They only use Student t-tests. These can only be used when data are continuous, distributed uniformly and only two samples are compared; if more than 2 samples, distributed uniformly, then use One-Way ANOVA and multiple comparisons tests. If data are categorical, use Chi-Square.

We have double checked and compared the experimental group to the control separately using the Student t-tests throughout the study.

Other points for improvement:

Figure 2E,F: what are GFP puncta and how are they counted?

I. Each GFP puncta looks like a little circle, likely representing a functional or dysfunctional structure. The biology of the GFP puncta is currently unkonwn.

II. We used the ImageJ to quantify the GFP puncta:

(1) Image- type-8 bits

(2) Process-subtract background (Rolling ball radio:10)

(3) Image-Adjust-Threshold-Apply

(4) Analyze-Measure-set measurements-choose “area” “limit to threshold”-OK

(5) Count the puncta number in the choosing area.

(6) Get the number of puncta per square micron.

All genotypes must be provided (including for MARCM clones), currently they are not.

We have shown the full genotype in the corresponding legend.

Figure 7O,P indicate on figure that these are RNAi

We have revised the labels to RNAi in Figure 7O,P.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations For The Authors):

Several typos are present in the text.

We have read the manuscript carefully and corrected typos throughout.

-

eLife assessment

This study represents a valuable finding on the neuron-glia communication and glial responses to traumatic brain injury (TBI). The data supporting the authors' conclusions on TBI analysis, RNA-seq on FACS sorted astrocytes, genetic analyses on Pvr-JNK/MMP1 are solid. However, cellular aspects of the response to TBI, statistical analysis, and molecular links between Pvr-AP1 are incomplete, which could be further strengthened in the future by more rigorous analyses.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Li et al report that upon traumatic brain injury (TBI), Pvr signalling in astrocytes activates the JNK pathway and up-regulates the expression of the well-known JNK target MMP1. The FACS sort astrocytes, and carry out RNAseq analysis, which identifies pvr as well as genes of the JNK pathway as particularly up-regulated after TBI. They use conventional genetics loss of function, gain of function and epistasis analysis with and without TBI to verify the involvement of the JNK-MMP1 signalling pathway downstream of PVR. They also show that blocking endocytosis prolongs the involvement of this pathway in the TBI response.

The strengths are that multiple experiments are used to demonstrate that TBI in their hands damaged the BBB, induced apoptosis and increased MMP1 levels. The RNAseq analysis on FACS sorted …

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Li et al report that upon traumatic brain injury (TBI), Pvr signalling in astrocytes activates the JNK pathway and up-regulates the expression of the well-known JNK target MMP1. The FACS sort astrocytes, and carry out RNAseq analysis, which identifies pvr as well as genes of the JNK pathway as particularly up-regulated after TBI. They use conventional genetics loss of function, gain of function and epistasis analysis with and without TBI to verify the involvement of the JNK-MMP1 signalling pathway downstream of PVR. They also show that blocking endocytosis prolongs the involvement of this pathway in the TBI response.

The strengths are that multiple experiments are used to demonstrate that TBI in their hands damaged the BBB, induced apoptosis and increased MMP1 levels. The RNAseq analysis on FACS sorted astrocytes is nice and will be valuable to scientists beyond the confines of this paper. The functional genetic analysis is conventional, yet sound, and supports claims of JNK and MMP1 functioning downstream of Pvr in the TBI context.

For this revised version the authors have removed all the unsupported claims. This renders their remaining claims more solid. However, it has resulted in the loss of important cellular aspects of the response to TBI, limiting the scope and value of the work.

The main weakness is that novelty and insight are both rather limited. Others had previously published that both JNK signalling and MMP1 were activated upon injury, in multiple contexts (as well as the articles cited by the authors, they should also see Losada-Perez et al 2021). That Pvr can regulate JNK signalling was also known (Ishimaru et al 2004). The authors claim that the novelty was investigating injury responses in astrocytes in Drosophila. However, others had investigated injury responses by astrocytes in Drosophila before. It had been previously shown that astrocytes - defined as the Prospero+ neuropile glia, and also sharing evolutionary features with mammalian NG2 glia - respond to injury both in larval ventral nerve cords and in adult brains, where they proliferate regenerating glia and induce a neurogenic response (Kato et al 2011; Losada-Perez et al 2016; Harrison et al 2021; Simoes et al 2022). The authors argue that the novelty of the work is the investigation of the response of astrocytes to TBI. However, this is of somewhat limited scope. The authors mention that MMP1 regulates tissue remodelling, the inflammatory process and cancer. Exploring these functions further would have been an interesting addition, but the authors did not investigate what consequences the up-regulation of MMP1 after injury has in repair or regeneration processes.

The statistical analysis is incorrect in places, and this could affect the validity of some claims.

Altogether, this is an interesting and valuable addition to the repertoire of articles investigating neuron-glia communication and glial responses to injury in the Drosophila central nervous system (CNS). It is good and important to see this research area in Drosophila grow. This community together is building a compelling case for using Drosophila and its unparalleled powerful genetics to investigate nervous system injury, regeneration and repair, with important implications. Thus, this paper will be of interest to scientists investigating injury responses in the CNS using Drosophila, other model organisms (eg mice, fish) and humans.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In this study, authors used the Drosophila model to characterize molecular details underlying traumatic brain injury (TBI). Authors used the transcriptomic analysis of astrocytes collected by FACS sorting of cells derived from Drosophila heads following brain injury and identified upregulation of multiple genes, such as Pvr receptor, Jun, Fos, and MMP1. Additional studies identified that Pvr positively activates AP-1 transciption factor (TF) complex consisting of Jun and Fos, of which activation leads to the induction of MMP1. Finally, authors found that disruption of endocytosis and endocytotic trafficking facilitates Pvr signaling and subsequently leads to induction of AP-1 and MMP1.

Overall, this study provides important clues to understanding molecular mechanisms underlying TBI. The identified molecules …

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In this study, authors used the Drosophila model to characterize molecular details underlying traumatic brain injury (TBI). Authors used the transcriptomic analysis of astrocytes collected by FACS sorting of cells derived from Drosophila heads following brain injury and identified upregulation of multiple genes, such as Pvr receptor, Jun, Fos, and MMP1. Additional studies identified that Pvr positively activates AP-1 transciption factor (TF) complex consisting of Jun and Fos, of which activation leads to the induction of MMP1. Finally, authors found that disruption of endocytosis and endocytotic trafficking facilitates Pvr signaling and subsequently leads to induction of AP-1 and MMP1.

Overall, this study provides important clues to understanding molecular mechanisms underlying TBI. The identified molecules linked to TBI in astrocytes could be potential targets for developing effective therapeutics. The obtained data from transcriptional profiling of astrocytes will be useful for future follow-up studies. The manuscript is well-organized and easy to read.

However, the connection suggested by the authors between Pvr and AP-1, potentially mediated through the JNK pathway, lacks strong experimental support in my view. It's important to recognize that AP-1 activity is influenced by multiple upstream signaling pathways, not just the JNK pathway, which is the most well-characterized among them. Therefore, assuming that AP-1 transcriptional activity solely reflects the activity of the JNK pathway without additional direct evidence is unwarranted. To strengthen their argument, the study could benefit from direct evidence implicating the JNK pathway in linking Pvr to AP-1. This could be achieved through genetic studies involving mutants or transgenes targeting key components of the JNK pathway, such as Bsk and Hep, the Drosophila homologues of JNK and JNKK, respectively. Alternatively, employing p-JNK antibody-based techniques like Western blotting, while considering the potential challenges associated with p-JNK immunohistochemistry, could provide further validation. This important criticism regarding the molecular link between Pvr and AP-1 has been overlooked.

-

-

eLife assessment

This study represents a valuable finding on the neuron-glia communication and glial responses to traumatic brain injury (TBI). The data supporting the authors' conclusions on TBI analysis, RNA-seq on FACS sorted astrocytes, genetic analyses on Pvr-JNK/MMP1 are solid. However, astrocyte proliferation upon TBI and some of the quantitative methods are incomplete, which could be further strengthened by more rigorous analyses.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Li et al report that upon traumatic brain injury (TBI), Pvr signalling in astrocytes activates the JNK pathway and up-regulates the expression of the well-known JNK target MMP1. The FACS sort astrocytes, and carry out RNAseq analysis, which identifies pvr as well as genes of the JNK pathway as particularly up-regulated after TBI. They use conventional genetics loss of function, gain of function and epistasis analysis with and without TBI to verify the involvement of the Pvr-JNK-MMP1 signalling pathway.

The strengths are that multiple experiments are used to demonstrate that TBI in their hands damaged the BBB, induced apoptosis and increased MMP1 levels. The RNAseq analysis on FACS sorted astrocytes is nice and will be valuable to scientists beyond the confines of this paper. The functional genetic analysis …

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Li et al report that upon traumatic brain injury (TBI), Pvr signalling in astrocytes activates the JNK pathway and up-regulates the expression of the well-known JNK target MMP1. The FACS sort astrocytes, and carry out RNAseq analysis, which identifies pvr as well as genes of the JNK pathway as particularly up-regulated after TBI. They use conventional genetics loss of function, gain of function and epistasis analysis with and without TBI to verify the involvement of the Pvr-JNK-MMP1 signalling pathway.

The strengths are that multiple experiments are used to demonstrate that TBI in their hands damaged the BBB, induced apoptosis and increased MMP1 levels. The RNAseq analysis on FACS sorted astrocytes is nice and will be valuable to scientists beyond the confines of this paper. The functional genetic analysis is conventional, yet sound, and supports claims of JNK and MMP1 functioning downstream of Pvr in the TBI context.

However, the weaknesses are that novelty and insight are both rather limited, some data are incomplete and other data do not support some claims. Some approaches used lacked resolution and some experiments lacked rigour. The authors may wish to improve some of their data as this would make their case more convincing. Alternatively, they should remove unsupported claims.

Novelty and insight:

Others had previously published that both JNK signalling and MMP1 were activated upon injury, in multiple contexts (as well as the articles cited by the authors, they should also see Losada-Perez et al 2021). That Pvr can regulate JNK signalling was also known (Ishimaru et al 2004). And it was also known that astrocytes can respond to injury by proliferating, both in larval ventral nerve cords and adult brains (Kato et al 2011; Losada-Perez et al 2016; Harrison et al 2021; Simoes et al 2022). The authors argue that the novelty of the work is the investigation of the response of astrocytes to TBI. However, this is of somewhat limited scope. The authors mention that Mmp1 regulates tissue remodelling, the inflammatory process and cancer. Exploring these functions further would have been an interesting addition, but the authors do not investigate what consequences the up-regulation of Mmp1 after injury has in repair or regeneration processes.Incomplete or unconvincing data:

The authors failed to detect PCNA-GFP and pH3 in brains after TBI and conclude that that TBI does not induce astrocyte proliferation. However, this is a surprising claim, as it would be rather different from all previous prevalent observations of cell proliferation induced by injury. Cell proliferation can be notoriously difficult to detect (ie due to timing and sample size), thus instead this raises doubts on the experimental protocol or execution.

Others have previously reported: cells in S- phase using PCNA-GFP and other reporters (eg BrdU, EdU, FUCCI) in the intact adult brain (Kato et al 2009; Foo et al 2017; Li et al 2020; Fernandez-Hernandez et al 2013; Simoes et al 2022); that injury to the adult brain and VNC induces cell proliferation that can be detected with cell proliferation markers like BrdU, Myc, FUCCI and the mitotic marker pH3 (Kato et al 2009; Fernandez-Hernandez et al 2013; Losada-Perez et al 2021; Simoes et al 2022); and that injury to the brain and CNS induces glial proliferation in adult and larval brains/CNS, specifically of astrocytes (Kato et al 2011; Losada-Perez et al 2016; Fernandez-Hernandez et al 2013; Simoes et al 2022). Thus, the fact that they did not observe PCNAGFP+ cells in control, intact adult brains nor after TBI could suggest that they had technical, experimental difficulties. Detecting mitotic cells with anti-pH3 is difficult because M phase is very brief, but others have succeeded (Simoes et al 2022). Given that in all previous reports mentioned above cells were seen to proliferate after injury in the CNS, it would be rather surprising if no cell proliferation occurred after TBI. Resolving this conflicting result is important, as it could imply that TBI induces very different cellular responses from various other lesions or injury types. It is conceivably not impossible, but the most parsimonious start point would be that multiple injury types could cause equivalent responses in cells. Thus, the authors ought to consider whether technical or experimental design problems affected their experimental outcome instead.Other claims not supported by data:

(1) astrocyte hypertrophy, as the tools used do not have the resolution to support this claim;(2) localisation of anti-Pvr to specific cells, as the images show uniform signal or background instead;

(3) astrocytes do not engulf cell debris after TBI, as the tools and images do not have the resolution to make this claim.

The authors could improve these data with alternative experiments to maintain the claims; alternatively, these unsupported claims should be removed.

Statistical analysis:

The statistical analysis needs revising as it is wrong in multiple places. Revising the statistics will also require revision of the validity of the claims and adjusting interpretations accordingly.Altogether, this is an interesting and valuable addition to the repertoire of articles investigating neuron-glia communication and glial responses to injury in the Drosophila central nervous system (CNS). It is good and important to see this research area in Drosophila grow. This community together is building a compelling case for using Drosophila and its unparalleled powerful genetics to investigate nervous system injury, regeneration and repair, with important implications. Thus, this paper will be of interest to scientists investigating injury responses in the CNS using Drosophila, other model organisms (eg mice, fish) and humans.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

In this study, Li et al. examined the involvement of astrocyte-like glia in responding to traumatic brain injury in Drosophila. Using a previously-established method that induces high-impact, whole-body trauma to flies (HIT device), the authors observed increased blood-brain-barrier permeabilization, neuronal cell death, and hypertrophy of astrocyte-like cells in the fly brain following injury. The authors provide compelling evidence implicating a signaling pathway involving the PDGF/VEGF-like Pvr receptor tyrosine kinase, the AP-1 transcription factor, and the matrix metalloprotease Mmp1 in the astrocytic cell response to TBI. The authors' data was generally high-quality data and combined multiple experimental approaches (microscopy, RNA sequencing, and transgenic), increasing the rigor of the study. The …

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

In this study, Li et al. examined the involvement of astrocyte-like glia in responding to traumatic brain injury in Drosophila. Using a previously-established method that induces high-impact, whole-body trauma to flies (HIT device), the authors observed increased blood-brain-barrier permeabilization, neuronal cell death, and hypertrophy of astrocyte-like cells in the fly brain following injury. The authors provide compelling evidence implicating a signaling pathway involving the PDGF/VEGF-like Pvr receptor tyrosine kinase, the AP-1 transcription factor, and the matrix metalloprotease Mmp1 in the astrocytic cell response to TBI. The authors' data was generally high-quality data and combined multiple experimental approaches (microscopy, RNA sequencing, and transgenic), increasing the rigor of the study. The identification of injury-induced gene expression changes in astrocytic cells helps increase our limited understanding of roles this glial subtype plays in the adult fly brain. Limitations of the study include a reliance on RNAi-mediated gene silencing without validation via genetic mutants and a limited examination of how astrocyte-like and ensheathing glia could interact following TBI, especially given that several genes identified in this study are known to mediate ensheathing glial responses to axotomy. The conclusions are generally well-supported by the presented data, however some further clarification of quantitative methods and analyses will help to strengthen the findings:

1. The significance and quantification method for the astrocytic cell body sizes in Fig. 2C, D and appearance of GFP+ accumulations in Fig. 2F should be better defined - how were cell bodies and GFP+ puncta identified relative to other astrocytic cell structures, are they homogeneous in size/intensity in different brain regions following injury, and what could the GFP+ puncta represent?

2. The relative contributions of astrocyte-like and ensheathing glia in the brain's response to TBI is unclear. RNA sequencing identified Mmp1 and Draper as genes upregulated following TBI, however, these genes have previously been implicated in ensheathing glial (and not astrocytic) responses to acute nerve injury. The authors provide convincing evidence that their transcriptomic data is devoid of neuronal genes, but what about the possibility of ensheathing glial contaminants? Figures 2I-Q suggest that the majority of Mmp1 protein co-localizes with ensheathing rather than astrocytic glial membranes following TBI. Does knockdown of Pvr, Jra, or kay in ensheathing glia affect Mmp1 upregulation following injury? A closer examination of how these two glial subtypes contribute to and interact-and what proportion of Mmp1 is cell autonomous to astrocytes-during injury responses would be valuable.

3. The authors rely on RNAi and overexpression methods to manipulate expression of candidate genes in Figures 4, 5, and 7. In most cases, only a single RNAi line is used to reduce expression of a candidate gene, increasing the possibilities of off-target effects or insufficient gene knockdown. These data could be strengthened by using multiple RNAi lines as well as mutants to validate findings for Pvr, Jra, and kay knockdown in Figures 4 and 5, and perhaps confirmation of knockdown efficiency, particularly in Fig. 7.

4. Single channel images should be included in Fig. 1L and M to help strengthen the conclusion that Dcp-1+ puncta are elav+ and repo-.

5. Sample sizes and a description of power analysis should be included in figure legends/methods. Based on the graphs, some sample sizes appear low (e.g., Fig. 1H+K and 2D+Q). -

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In this study, authors used the Drosophila model to characterize molecular details underlying traumatic brain injury (TBI). The authors used the transcriptomic analysis of astrocytes collected by FACS sorting of cells derived from Drosophila heads following brain injury and identified upregulation of multiple genes, such as Pvr receptor, Jun, Fos, and MMP1. Additional studies identified that Pvr positively activates AP-1 transciption factor (TF) complex consisting of Jun and Fos, of which activation leads to the induction of MMP1. Finally, authors found that disruption of endocytosis and endocytotic trafficking facilitates Pvr signaling and subsequently leads to induction of AP-1 and MMP1.

Overall, this study provides important clues to understanding molecular mechanisms underlying TBI. The identified …

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In this study, authors used the Drosophila model to characterize molecular details underlying traumatic brain injury (TBI). The authors used the transcriptomic analysis of astrocytes collected by FACS sorting of cells derived from Drosophila heads following brain injury and identified upregulation of multiple genes, such as Pvr receptor, Jun, Fos, and MMP1. Additional studies identified that Pvr positively activates AP-1 transciption factor (TF) complex consisting of Jun and Fos, of which activation leads to the induction of MMP1. Finally, authors found that disruption of endocytosis and endocytotic trafficking facilitates Pvr signaling and subsequently leads to induction of AP-1 and MMP1.

Overall, this study provides important clues to understanding molecular mechanisms underlying TBI. The identified molecules linked to TBI in astrocytes could be potential targets for developing effective therapeutics. The obtained data from transcriptional profiling of astrocytes will be useful for future follow-up studies. The manuscript is well-organized and easy to read. However, I would like to request the authors to address the following issue to improve the quality of their study.

It is unclear why the authors did not explore the involvement of the JNK pathway in their study. While they described the potential involvement of the JNK pathway based on previous literature, they did not include any evidence on the JNK pathway in their own study.

It is important to note that the mechanism by which JNK activates AP-1 is primarily through phosphorylation, not the quantitative control of amounts, as much as I know. This raises questions about the authors' proposed hierarchical relationship between Pvr and AP-1 and the potential involvement of the JNK pathway in mediating this relationship.

Given the significance of the mechanistic link between Pvr and AP-1 in solidifying the authors' conclusion, it would have been beneficial for them to explore the involvement of the JNK pathway in their study, even if only minimally. The lack of such exploration may weaken the overall strength of their findings and the potential implications for understanding TBI.

-