Asymmetric inheritance of centrosomes maintains stem cell properties in human neural progenitor cells

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

eLife assessment

This manuscript reports important findings in the field of developmental neurobiology, particularly in our understanding of human cortical development. The methods, data, and analyses are solid yet, the lack of clonal resolution or timelapse imaging makes it hard to assess whether the inheritance of centrosomes occurs as the authors claim.

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

During human forebrain development, neural progenitor cells (NPCs) in the ventricular zone (VZ) undergo asymmetric cell divisions to produce a self-renewed progenitor cell, maintaining the potential to go through additional rounds of cell divisions, and differentiating daughter cells, populating the developing cortex. Previous work in the embryonic rodent brain suggested that the preferential inheritance of the pre-existing (older) centrosome to the self-renewed progenitor cell is required to maintain stem cell properties, ensuring proper neurogenesis. If asymmetric segregation of centrosomes occurs in NPCs of the developing human brain, which depends on unique molecular regulators and species-specific cellular composition, remains unknown. Using a novel, recombination-induced tag exchange-based genetic tool to birthdate and track the segregation of centrosomes over multiple cell divisions in human embryonic stem cell-derived regionalised forebrain organoids, we show the preferential inheritance of the older mother centrosome towards self-renewed NPCs. Aberration of asymmetric segregation of centrosomes by genetic manipulation of the centrosomal, microtubule-associated protein Ninein alters fate decisions of NPCs and their maintenance in the VZ of human cortical organoids. Thus, the data described here use a novel genetic approach to birthdate centrosomes in human cells and identify asymmetric inheritance of centrosomes as a mechanism to maintain self-renewal properties and to ensure proper neurogenesis in human NPCs.

Article activity feed

-

-

Author Response

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The manuscript by Royall et al. builds on previous work in the mouse that indicates that neural progenitor cells (NPCs) undergo asymmetric inheritance of centrosomes and provides evidence that a similar process occurs in human NPCs, which was previously unknown.

The authors use hESC-derived forebrain organoids and develop a novel recombination tag-induced genetic tool to birthdate and track the segregation of centrosomes in NPCs over multiple divisions. The thoughtful experiments yield data that are concise and well-controlled, and the data support the asymmetric segregation of centrosomes in NPCs. These data indicate that at least apical NPCs in humans undergo asymmetric centrosome inheritance. The authors attempt to disrupt the process and present some data that there may be …

Author Response

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The manuscript by Royall et al. builds on previous work in the mouse that indicates that neural progenitor cells (NPCs) undergo asymmetric inheritance of centrosomes and provides evidence that a similar process occurs in human NPCs, which was previously unknown.

The authors use hESC-derived forebrain organoids and develop a novel recombination tag-induced genetic tool to birthdate and track the segregation of centrosomes in NPCs over multiple divisions. The thoughtful experiments yield data that are concise and well-controlled, and the data support the asymmetric segregation of centrosomes in NPCs. These data indicate that at least apical NPCs in humans undergo asymmetric centrosome inheritance. The authors attempt to disrupt the process and present some data that there may be differences in cell fate, but this conclusion would be better supported by a better assessment of the fate of these different NPCs (e.g. NPCs versus new neurons) and would support the conclusion that younger centriole is inherited by new neurons.

We thank the reviewer for their supportive comments (“…thoughtful experiments yield data that are concise and well-controlled…”).

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Royall et al. examine the asymmetric inheritance of centrosomes during human brain development. In agreement with previous studies in mice, their data suggest that the older centrosome is inherited by the self-renewing daughter cell, whereas the younger centrosome is inherited by the differentiating daughter cell. The key importance of this study is to show that this phenomenon takes place during human brain development, which the authors achieved by utilizing forebrain organoids as a model system and applying the recombination-induced tag exchange (RITE) technology to birthdate and track the centrosomes.

Overall, the study is well executed and brings new insights of general interest for cell and developmental biology with particular relevance to developmental neurobiology. The Discussion is excellent, it brings this study into the context of previous work and proposes very appealing suggestions on the evolutionary relevance and underlying mechanisms of the asymmetric inheritance of centrosomes. The main weakness of the study is that it tackles asymmetric inheritance only using fixed organoid samples. Although the authors developed a reasonable mode to assign the clonal relationships in their images, this study would be much stronger if the authors could apply time-lapse microscopy to show the asymmetric inheritance of centrosomes.

We thank the reviewer for their constructive and supportive comments (“…the study is well executed and brings new insights of general interest for cell and developmental biology with particular relevance to developmental neurobiology….”). We understand the request for clonal data or dynamic analyses in organoids (e.g., using time-lapse microscopy). We also agree that such data would certainly strengthen our findings. However, as outlined above (please refer to point #1 of the editorial summary), this is unfortunately currently not feasible. However, we have explicitly discussed this shortcoming in our revised manuscript and why future experiments (with advanced methodology) will have to do these experiments.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In this manuscript, the authors report that human cortical radial glia asymmetrically segregates newly produced or old centrosomes after mitosis, depending on the fate of the daughter cell, similar to what was previously demonstrated for mouse neocortical radial glia (Wang et al. 2009). To do this, the authors develop a novel centrosome labelling strategy in human ESCs that allows recombination-dependent switching of tagged fluorescent reporters from old to newly produced centrosome protein, centriolin. The authors then generate human cortical organoids from these hESCs to show that radial glia in the ventricular zone retains older centrosomes whereas differentiated cells, i.e. neurons, inherit the newly produced centrosome after mitosis. The authors then knock down a critical regulator of asymmetric centrosome inheritance called Ninein, which leads to a randomization of this process, similar to what was observed in mouse cortical radial glia.

A major strength of the study is the combined use of the centrosome labelling strategy with human cortical organoids to address an important biological question in human tissue. This study is similarly presented as the one performed in mice (Wang et al. 2009) and the existence of the asymmetric inheritance mechanism of centrosomes in another species grants strength to the main claim proposed by the authors. It is a well-written, concise article, and the experiments are well-designed. The authors achieve the aims they set out in the beginning, and this is one of the perfect examples of the right use of human cortical organoids to study an important phenomenon. However, there are some key controls that would elevate the main conclusions considerably.

We thank the reviewer for their overall support of our findings (“..authors achieve the aims they set out in the beginning, and this is one of the perfect examples of the right use of human cortical organoids to study an important phenomenon…”). We also understand the reviewer’s request for additional experiments/controls that “…would elevate the main conclusions considerably.”

- The lack of clonal resolution or timelapse imaging makes it hard to assess whether the inheritance of centrosomes occurs as the authors claim. The authors show that there is an increase in newly made non-ventricular centrosomes at a population level but without labelling clones and demonstrating that a new or old centrosome is inherited asymmetrically in a dividing radial glia would grant additional credence to the central conclusion of the paper. These experiments will put away any doubt about the existence of this mechanism in human radial glia, especially if it is demonstrated using timelapse imaging. Additionally, knowing the proportions of symmetric vs asymmetrically dividing cells generating old/new centrosomes will provide important insights pertinent to the conclusions of the paper. Alternatively, the authors could soften their conclusions, especially for Fig 2.

We understand the reviewer’s request. As outlined above (please refer to point #1 of the editorial summary), we had tried previously to add data using single cell timelapse imaging. However, due to the size and therefore weakness of the fluorescent signal we had failed despite extensive efforts. According to the reviewer’s suggestion we have now explicitly discussed this shortcoming and softened our conclusions.

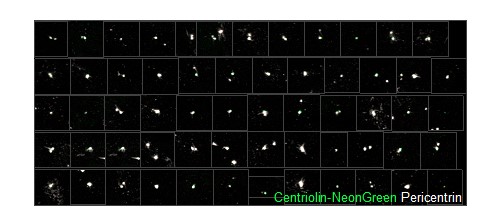

- Some critical controls are missing. In Fig. 1B, there is a green dot that does not colocalize with Pericentrin. This is worrying and providing rigorous quantifications of the number of green and tdTom dots with Pericentrin would be very helpful to validate the labelling strategy. Quantifications would put these doubts to rest. Additionally, an example pericentrin staining with the GFP/TdTom signal in figure 4 would also give confidence to the reader. For figure 4, having a control for the retroviral infection is important. Although the authors show a convincing phenotype, the effect might be underestimated due to the incomplete infection of all the analyzed cells.

We have included more rigorous quantifications in our revised manuscript.

For Figure 1: There are indeed some green speckles that might be misinterpreted as a green centrosome. However, the speckles are usually smaller and by applying a strict size requirement we exclude speckles. To check whether the classifier might interpret any speckles as centrosomes, we manually checked 60 green “dots” that were annotated as centrosome. From these images all green spots detected as centrosome co-localized with Pericentrin signal (Images shown in Author response image 1).

For Figure 4: as we are comparing cells that were either infected with a retrovirus expressing scrambled or Ninein-targeting shRNA we compare cells that experienced a similar treatment. Besides that, only cells infected with the virus express Cre-ERT2 whereby only the centrosomes of targeted cells were analyzed. Accordingly, we only compare cells expressing scrambled or Ninein-targeting shRNA, all surrounding “wt” cells are not considered.

Author response image 1.

Pictures used to test the classifier. Each of the green “dots” recognized by the classifier as a Centriolin-NeonGreen-containing centrosome (green) co-localized with Pericentrin signal (white).

- It would be helpful if the authors expand on the presence of old centrosomes in apical radial glia vs outer radial glia. Currently, in figure 3, the authors only focus on Sox2+ cells but this could be complemented with the inclusion of markers for outer radial glia and whether older centrosomes are also inherited by oRGCs. This would have important implications on whether symmetric/asymmetric division influences the segregation of new/old centrosomes.

That is an interesting question and we do agree that additional analyses, stratified by ventricular vs. oRGCs would be interesting. However, at the time points analysed there are only very few oRGCs present (if any) in human ESC-derived organoids (Qian et al., Cell, 2016). However, we have now added this point for future experiments to our discussion.

-

eLife assessment

This manuscript reports important findings in the field of developmental neurobiology, particularly in our understanding of human cortical development. The methods, data, and analyses are solid yet, the lack of clonal resolution or timelapse imaging makes it hard to assess whether the inheritance of centrosomes occurs as the authors claim.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The manuscript by Royall et al. builds on previous work in the mouse that indicates that neural progenitor cells (NPCs) undergo asymmetric inheritance of centrosomes and provides evidence that a similar process occurs in human NPCs, which was previously unknown.

The authors use hESC-derived forebrain organoids and develop a novel recombination tag-induced genetic tool to birthdate and track the segregation of centrosomes in NPCs over multiple divisions. The thoughtful experiments yield data that are concise and well-controlled, and the data support the asymmetric segregation of centrosomes in NPCs. These data indicate that at least apical NPCs in humans undergo asymmetric centrosome inheritance. The authors attempt to disrupt the process and present some data that there may be differences in cell fate, but …

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The manuscript by Royall et al. builds on previous work in the mouse that indicates that neural progenitor cells (NPCs) undergo asymmetric inheritance of centrosomes and provides evidence that a similar process occurs in human NPCs, which was previously unknown.

The authors use hESC-derived forebrain organoids and develop a novel recombination tag-induced genetic tool to birthdate and track the segregation of centrosomes in NPCs over multiple divisions. The thoughtful experiments yield data that are concise and well-controlled, and the data support the asymmetric segregation of centrosomes in NPCs. These data indicate that at least apical NPCs in humans undergo asymmetric centrosome inheritance. The authors attempt to disrupt the process and present some data that there may be differences in cell fate, but this conclusion would be better supported by a better assessment of the fate of these different NPCs (e.g. NPCs versus new neurons) and would support the conclusion that younger centriole is inherited by new neurons.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Royall et al. examine the asymmetric inheritance of centrosomes during human brain development. In agreement with previous studies in mice, their data suggest that the older centrosome is inherited by the self-renewing daughter cell, whereas the younger centrosome is inherited by the differentiating daughter cell. The key importance of this study is to show that this phenomenon takes place during human brain development, which the authors achieved by utilizing forebrain organoids as a model system and applying the recombination-induced tag exchange (RITE) technology to birthdate and track the centrosomes.

Overall, the study is well executed and brings new insights of general interest for cell and developmental biology with particular relevance to developmental neurobiology. The Discussion is excellent, it …

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Royall et al. examine the asymmetric inheritance of centrosomes during human brain development. In agreement with previous studies in mice, their data suggest that the older centrosome is inherited by the self-renewing daughter cell, whereas the younger centrosome is inherited by the differentiating daughter cell. The key importance of this study is to show that this phenomenon takes place during human brain development, which the authors achieved by utilizing forebrain organoids as a model system and applying the recombination-induced tag exchange (RITE) technology to birthdate and track the centrosomes.

Overall, the study is well executed and brings new insights of general interest for cell and developmental biology with particular relevance to developmental neurobiology. The Discussion is excellent, it brings this study into the context of previous work and proposes very appealing suggestions on the evolutionary relevance and underlying mechanisms of the asymmetric inheritance of centrosomes. The main weakness of the study is that it tackles asymmetric inheritance only using fixed organoid samples. Although the authors developed a reasonable mode to assign the clonal relationships in their images, this study would be much stronger if the authors could apply time-lapse microscopy to show the asymmetric inheritance of centrosomes.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In this manuscript, the authors report that human cortical radial glia asymmetrically segregates newly produced or old centrosomes after mitosis, depending on the fate of the daughter cell, similar to what was previously demonstrated for mouse neocortical radial glia (Wang et al. 2009). To do this, the authors develop a novel centrosome labelling strategy in human ESCs that allows recombination-dependent switching of tagged fluorescent reporters from old to newly produced centrosome protein, centriolin. The authors then generate human cortical organoids from these hESCs to show that radial glia in the ventricular zone retains older centrosomes whereas differentiated cells, i.e. neurons, inherit the newly produced centrosome after mitosis. The authors then knock down a critical regulator of asymmetric …

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

In this manuscript, the authors report that human cortical radial glia asymmetrically segregates newly produced or old centrosomes after mitosis, depending on the fate of the daughter cell, similar to what was previously demonstrated for mouse neocortical radial glia (Wang et al. 2009). To do this, the authors develop a novel centrosome labelling strategy in human ESCs that allows recombination-dependent switching of tagged fluorescent reporters from old to newly produced centrosome protein, centriolin. The authors then generate human cortical organoids from these hESCs to show that radial glia in the ventricular zone retains older centrosomes whereas differentiated cells, i.e. neurons, inherit the newly produced centrosome after mitosis. The authors then knock down a critical regulator of asymmetric centrosome inheritance called Ninein, which leads to a randomization of this process, similar to what was observed in mouse cortical radial glia.

A major strength of the study is the combined use of the centrosome labelling strategy with human cortical organoids to address an important biological question in human tissue. This study is similarly presented as the one performed in mice (Wang et al. 2009) and the existence of the asymmetric inheritance mechanism of centrosomes in another species grants strength to the main claim proposed by the authors. It is a well-written, concise article, and the experiments are well-designed. The authors achieve the aims they set out in the beginning, and this is one of the perfect examples of the right use of human cortical organoids to study an important phenomenon. However, there are some key controls that would elevate the main conclusions considerably.

- The lack of clonal resolution or timelapse imaging makes it hard to assess whether the inheritance of centrosomes occurs as the authors claim. The authors show that there is an increase in newly made non-ventricular centrosomes at a population level but without labelling clones and demonstrating that a new or old centrosome is inherited asymmetrically in a dividing radial glia would grant additional credence to the central conclusion of the paper. These experiments will put away any doubt about the existence of this mechanism in human radial glia, especially if it is demonstrated using timelapse imaging. Additionally, knowing the proportions of symmetric vs asymmetrically dividing cells generating old/new centrosomes will provide important insights pertinent to the conclusions of the paper. Alternatively, the authors could soften their conclusions, especially for Fig 2.

- Some critical controls are missing. In Fig. 1B, there is a green dot that does not colocalize with Pericentrin. This is worrying and providing rigorous quantifications of the number of green and tdTom dots with Pericentrin would be very helpful to validate the labelling strategy. Quantifications would put these doubts to rest. Additionally, an example pericentrin staining with the GFP/TdTom signal in figure 4 would also give confidence to the reader. For figure 4, having a control for the retroviral infection is important. Although the authors show a convincing phenotype, the effect might be underestimated due to the incomplete infection of all the analyzed cells.

- It would be helpful if the authors expand on the presence of old centrosomes in apical radial glia vs outer radial glia. Currently, in figure 3, the authors only focus on Sox2+ cells but this could be complemented with the inclusion of markers for outer radial glia and whether older centrosomes are also inherited by oRGCs. This would have important implications on whether symmetric/asymmetric division influences the segregation of new/old centrosomes.

-