Mechanisms and functions of respiration-driven gamma oscillations in the primary olfactory cortex

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

eLife assessment

This fundamental study employs a publicly available dataset to examine the role of gamma oscillations in the coding of olfactory information in the mouse piriform cortex. The authors convincingly show that gamma originates in the piriform cortex, is driven by feedback inhibition, and that the time course of odour decoding is most accurate when gamma oscillations are strongest. This work is relevant to a wide audience interested in the mechanisms and role of oscillations in the brain, and nicely demonstrates the benefits of well-curated, publicly available datasets.

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

Gamma oscillations are believed to underlie cognitive processes by shaping the formation of transient neuronal partnerships on a millisecond scale. These oscillations are coupled to the phase of breathing cycles in several brain areas, possibly reflecting local computations driven by sensory inputs sampled at each breath. Here, we investigated the mechanisms and functions of gamma oscillations in the piriform (olfactory) cortex of awake mice to understand their dependence on breathing and how they relate to local spiking activity. Mechanistically, we find that respiration drives gamma oscillations in the piriform cortex, which correlate with local feedback inhibition and result from recurrent connections between local excitatory and inhibitory neuronal populations. Moreover, respiration-driven gamma oscillations are triggered by the activation of mitral/tufted cells in the olfactory bulb and are abolished during ketamine/xylazine anesthesia. Functionally, we demonstrate that they locally segregate neuronal assemblies through a winner-take-all computation leading to sparse odor coding during each breathing cycle. Our results shed new light on the mechanisms of gamma oscillations, bridging computation, cognition, and physiology.

Article activity feed

-

-

Author Response

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The authors used data from extracellular recordings in mouse piriform cortex (PCx) by Bolding & Franks (2018), they examined the strength, timing, and coherence of gamma oscillations with respiration in awake mice. During "spontaneous" activity (i.e. without odor or light stimulation), they observed a large peak in gamma that was driven by respiration and aligned with the spiking of FBIs. TeLC, which blocks synaptic output from principal cells onto other principal cells and FBIs, abolishes gamma. Beta oscillations are evoked while gamma oscillations are induced. Odors strongly affect beta in PCx but have minimal (duration but not amplitude) effects on gamma. Unlike gamma, strong, odor-evoked beta oscillations are observed in TeLC. Using PCA, the authors found a small subset of neurons that …

Author Response

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The authors used data from extracellular recordings in mouse piriform cortex (PCx) by Bolding & Franks (2018), they examined the strength, timing, and coherence of gamma oscillations with respiration in awake mice. During "spontaneous" activity (i.e. without odor or light stimulation), they observed a large peak in gamma that was driven by respiration and aligned with the spiking of FBIs. TeLC, which blocks synaptic output from principal cells onto other principal cells and FBIs, abolishes gamma. Beta oscillations are evoked while gamma oscillations are induced. Odors strongly affect beta in PCx but have minimal (duration but not amplitude) effects on gamma. Unlike gamma, strong, odor-evoked beta oscillations are observed in TeLC. Using PCA, the authors found a small subset of neurons that conveyed most of the information about the odor (winner cells). Loser cells were more phase-locked to gamma, which matched the time course of inhibition. Odor decoding accuracy closely follows the time course of gamma power.

We thank the reviewer for the accurate summary of our work.

I think this is an interesting study that uses a publicly available dataset to good effect and advances the field elegantly, especially by selectively analyzing activity in identified principal neurons versus inhibitory interneurons, and by making use of defined circuit perturbations to causally test some of their hypotheses.

We thank the reviewer for the positive appraisal.

Major:

- The authors show odor-specificity at the time of the gamma peak and imply that the gamma coupling is important for odor coding. Is this because gamma oscillations are important or because gamma is strongest when activity in PCx is strongest (i.e. both excitatory and inhibitory activity, which would cancel each other in the population PSTH, which peaks earlier)? To make this claim, the authors could show that odor decoding accuracy - with a small (~10 ms sliding window) - oscillates at approx. gamma frequencies. As is, Fig. 5 just shows that cells respond at slightly different times in the sniff cycle. What time window was used for computing the Odor Specificity Index? Put another way, is it meaningful that decoding is most accurate when gamma oscillations are strongest, or is this just a reflection of total population activity, i.e., when activity is greatest there is more gamma power, and odor decoding accuracy is best?

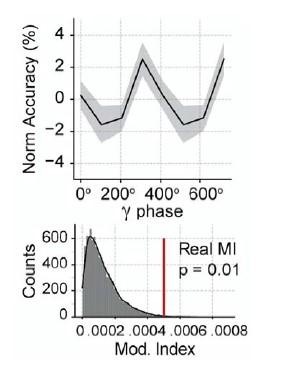

We thank the reviewer for the critical comment. Please note that the employed decoding strategy (supervised learning with cross-validation) prevents us from quantifying a time series of decoding accuracy. Nevertheless, to overcome this difficulty, we divided the spike data (0-500 ms following the inhalation start) according to the gamma cycle into four non-overlapping gamma phase bins. Then we tested whether odor decoding accuracy varied as a function of the gamma cycle phase. Using this approach, we found that decoding depended on the gamma phase, as shown below:

(The bottom plot shows the modulation of decoding accuracy within the gamma cycle [Real MI] compared to a surrogate distribution [Surr MI, obtained by circularly shifting the gamma phases by a random amount]).

We interpret this new result as indicative that gamma influences decoding accuracy directly and that our previous result was not only a reflection of total population activity. Moreover, please note that we only use the principal cell activity for computing the odor specificity index (Fig 5E) and decoding accuracy (Fig 7B). Both peak at ~150 ms following inhalation start, at a time window where the net principal cell activity is roughly similar to baseline levels (Fig 5A bottom panel).

These new panels were added to revised Figure 7 and mentioned in the revised manuscript (page 8); we now also discuss the above considerations about maximal decoding not coinciding with the peak firing rate (page 10).

Regarding the Odor Specificity Index computation, we apologize for not describing it appropriately in the corresponding Methods subsection. We employed the same sliding time window as in the population vector correlation and the decoding analyses (i.e., 100 ms window, 62.5 % overlap). This information has been added to the revised manuscript (page 15).

- The authors say, "assembly recruitment would depend on excitatory-excitatory interactions among winner cells occurring simultaneously during gamma activity." Can the authors test this prediction by examining the TeLC recordings, in which excitatory-excitatory connections are abolished?

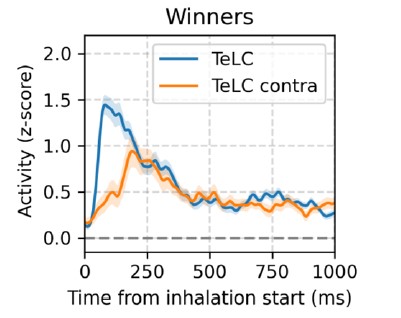

We thank the reviewer for the relevant comment. We followed the reviewer's suggestion and analyzed odor assemblies in TeLC recordings. Interestingly, we found a greater increase in the firing rate of winner cells in TeLC recordings (see figure below), which therefore does not support our previous interpretation that assembly recruitment would depend on excitatory-excitatory local interactions.

Thus, this new result suggests a much more critical role than we previously considered for the OB projections in determining winner neurons.

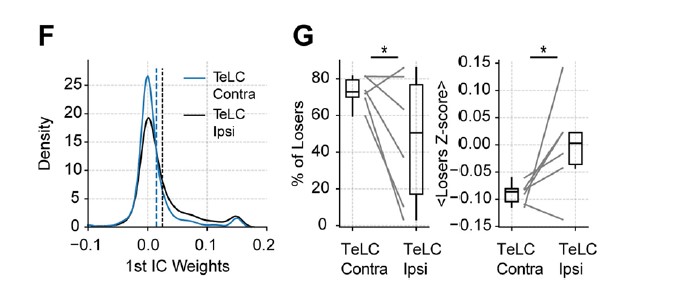

Moreover, we found significant differences in the properties of loser cells. In particular, the TeLC-infected piriform cortex showed a decreased number of losing cells, which were significantly less inhibited than their contralateral counterparts:

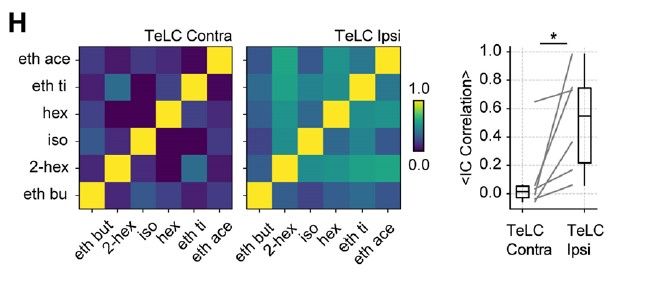

Furthermore, the reduced inhibition of losing cells was associated with an increased correlation of assembly weights across odors for the affected hemisphere:

Therefore, we believe these results highlight the role of gamma oscillations in segregating cell assemblies and generating a sparse orthogonal odor representation in the piriform cortex. These findings are now included as new panels of Figure 6 and discussed on page 8. Noteworthy, to conform with them, we modified our speculative sentence (page 9) "assembly recruitment would depend on excitatory-excitatory interactions among winner cells occurring simultaneously during gamma activity" to “(…) the assembly recruitment would depend on OB projections determining which winner cells “escape” gamma inhibition, highlighting the relevance of the OB-PCx interplay for olfaction (Chae et al., 2022; Otazu et al., 2015).”

- The authors show that gamma oscillations are abolished in the TeLC condition and use this to claim that gamma arises in the PCx. However, PCx neurons also project back to the OB, where they form excitatory connections onto granule cells. Fukunaga et al (2012) showed that granule cells are essential for generating gamma oscillations in the bulb. Can the authors be sure that gamma is generated in the PCx, per se, rather than generated in the bulb by centrifugal inputs from the PCx, and then inherited from the bulb by the PCx?

We thank the reviewer for the pertinent comment regarding gamma generation in the PCx. To address this point, we have performed current source density (CSD) analysis, which showed sink and sources of low-gamma oscillations within the PCx and also a phase reversal:

This result – shown as panel F in Figure 1 – suggests a local generation of gamma within the PCx. Along with the fact that PCx gamma tightly correlates with piriform FBI firing and that PCx gamma disappears in the TeLC ipsi hemisphere, which has intact OB projections, we deem it more parsimonious to assume that gamma does originate in the piriform circuit during feedback inhibition acting on principal cells and is not directly inherited from OB (though it depends on its drive). We have edited our text to incorporate the figure above panel (page 4). We now also relate our results with those of Fukunaga and colleagues for the OB gamma generation and discuss the alternative interpretation of inherited gamma (page 9).

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

This is a very interesting paper, in which the authors describe how respiration-driven gamma oscillations in the piriform cortex are generated. Using a published data set, they find evidence for a feedback loop between local principal cells and feedback interneurons (FBIs) as the main driver of respiration-driven gamma. Interestingly, odour-evoked gamma bursts coincide with the emergence of neuronal assemblies that activate when a given odour is presented. The results argue in favour of a winner-take-all mechanism of assembly generation that has previously been suggested on theoretical grounds.

We thank the reviewer for his/her work and accurate summary of our results.

The article is well-written and the claims are justified by the data. Overall, the manuscript provides novel key insights into the generation of gamma oscillations and a potential link to the encoding of sensory input by cell assemblies. I have only minor suggestions for additional analyses that could further strengthen the manuscript:

We thank the reviewer for the positive appraisal.

- The authors' analysis of firing rates of FFIs and FBIs combined with TeLC experiments make a compelling case for respiration-driven gamma being generated in a pyramidal cell-FBI feedback mechanism. This conclusion could be further strengthened by analyzing the gamma phase-coupling of the three neuronal populations investigated. One would expect strong coupling for FBIs but not FFIs (assuming that enough spikes of these populations could be sampled during the respiration-triggered gamma bursts). An additional analysis to strengthen this conclusion could be to extract FBI- and FFI spike-triggered gamma-filtered signals. One might expect an increase in gamma amplitude following FBI but not FFI spiking (see e.g., Pubmed ID 26890123).

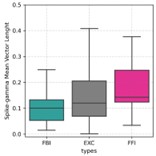

We thank the reviewer for the comment. To address this point, we first computed spike-coupling strength (by means of the Mean Vector Length – MVL) for each neuronal subtype. As shown below, we did not find major differences in MVL values across subtypes (if anything, the FBIs actually displayed the lowest MVL, though it should be cautioned that this metric is sensible to sample size, which differed among subtypes):

Of note, this result also translated to spike-triggered gamma-filtered signals, with FBIs having the lowest average. We don’t however believe these findings speak against a major role of FBIs in giving rise to field gamma, since it is expected that inhibited neurons will highly phase-lock to gamma (while more active neurons during gamma would show lower phase-locking). Nevertheless, we also computed the spike-triggered gamma amplitude envelope for all three neuronal subtypes. This analysis showed that gamma envelopes closely followed FBI spikes (and not FFIs or EXC cells), and thus this new result reinforces the idea that FBIs trigger gamma oscillations. This plot is now part of an inset of Figure 1G (described on page 5).

- The authors utilize the neurons' weight in the first PC to assign them to odour-related assemblies. This method convincingly extracts an assembly for each odour (when odours are used individually), and these seem to be virtually non-overlapping. It would be informative to test whether a similar clear separation of the individual assemblies could be achieved by running the analysis on all odours simultaneously, perhaps by employing a procedure of assembly extraction that allows to deal with overlapping assembly membership better than a pure PCA approach (as used for instance in the work cited on page 11, including the authors' previous work)? I do not doubt the validity of the authors' approach here at all, but the suggested additional analysis might allow the authors to increase their confidence that individual neurons contribute mostly to an assembly related to a single odour.

We thank the reviewer for the pertinent comment. In order to address it, we ran the ICA-based approach to detect cell assemblies (Lopes-dos-Santos et al., 2013) using the spike time series of all odors concatenated. The concatenation included time windows around the gamma peak (100-400 ms after inhalation start). We chose this window to prevent the ICA from picking temporal features of the response as different ICs instead of the spiking variations caused by the different odors. As a reference, we also calculated ICA for each odor independently during the gamma peak.

We found that the results obtained from ICA computed using concatenated data from all odors show important resemblances to those from the single ICA per odor approach. For instance, we get similar sparsity and cell assembly membership (Figure 6-figure supplement 1A), orthogonality (Figure 6-figure supplement 1B), and odor specificity (Figure 6-figure supplement 1C) in the ICs loadings through both approaches. Noteworthy, the average absolute IC correlation between the six odors (computed separately) and the six first ICs (computed from the combined odor responses) were similar across animals and showed no significant differences (Figure 6-figure supplement 1C).

We also directly tested odor selectivity and separation in the concatenated data approach by computing each odor’s mean assembly activity (i.e., “IC projection”). Regarding the former, we found that most assemblies coded for 1 or 2 odors (Figure 6-figure supplement 1D). Regarding the diversity of representations for the sampled neurons, we assessed odor separation by examining to which odor each IC is activated the most. Under this framework, we get that, on average, the first 6 ICs encode three to five different odors (Figure 6-figure supplement 1E).

We have included this result as a new Figure 6-figure supplement 1 and mention it on page 8. Of note, we have also performed all of our previous assembly analyses (i.e., Figure 6) using ICA instead of PCA to be consistent throughout the manuscript and allow the reader to compare with the new supplementary figure. This led to a new and enhanced version of Figure 6.

- Do the authors observe a slow drift in assembly membership as predicted from previous work showing slowly changing odour responses of principal neurons (Schoonover et al., 2021)? This could perhaps be quantified by looking at the expression strengths of assemblies at individual odour presentations or by running the PCA separately on the first and last third of the odour presentations to test whether the same neurons are still 'winners'.

We thank the reviewer for calling our attention to this point. We note, however, that the representation drift observed by Schoonover et al. occurred along several days of recordings, i.e., at a much slower time scale than the single-day recordings we analyzed here (of note, Schoonover et al. observed no drift within the same day [their Fig 2a]). But irrespective of this, we believe that the data at hand does not allow for a confident analysis of possible drifts. This is because each odor was only presented ~12 times; so, further subdividing the data into subsets of only 4 trials would not render a reliable analysis, unfortunately.

- Does the winner-take-all scenario involve the recruitment of specific sets of FBIs during the activation of the individual odour-selective assemblies? The authors could address this by testing whether the rate of FBIs changes differently with the activation of the extracted assemblies.

Within each recording session, the number of recorded FBIs is very low, on average 3.6 FBIs per recording session. Thus, unfortunately such interesting analysis cannot be confidently performed.

- Given the dependence on local gamma oscillations, one might expect that odour-selective assemblies do not emerge in the TeLC-expressing hemisphere. This could be directly tested in the existing data set.

We are thankful for the comment. We followed the reviewer's suggestion and analyzed odor assemblies in TeLC recordings, comparing the ipsilateral hemisphere (infected) with the contralateral one. Interestingly, we find an increased correlation of assembly weights across odors, suggesting that the formation/segregation of odor-selective assemblies is hindered when the principal cell synapses are abolished. This assembly selectivity reduction co-occurred as the number of losing neurons decreased, and the inhibition of the latter was also reduced. Consequently, decoding accuracy significantly decreased during the 150-250 ms window in the infected TeLC hemisphere compared to the contralateral cortex.

Therefore, we believe these new results support the role of gamma oscillations in segregating cell assemblies and generating a sparse orthogonal odor representation. These findings are now included as new panels of Figure 6 and Figure 7 and discussed on page 8.

-

eLife assessment

This fundamental study employs a publicly available dataset to examine the role of gamma oscillations in the coding of olfactory information in the mouse piriform cortex. The authors convincingly show that gamma originates in the piriform cortex, is driven by feedback inhibition, and that the time course of odour decoding is most accurate when gamma oscillations are strongest. This work is relevant to a wide audience interested in the mechanisms and role of oscillations in the brain, and nicely demonstrates the benefits of well-curated, publicly available datasets.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The authors used data from extracellular recordings in mouse piriform cortex (PCx) by Bolding & Franks (2018), they examined the strength, timing, and coherence of gamma oscillations with respiration in awake mice. During "spontaneous" activity (i.e. without odor or light stimulation), they observed a large peak in gamma that was driven by respiration and aligned with the spiking of FBIs. TeLC, which blocks synaptic output from principal cells onto other principal cells and FBIs, abolishes gamma. Beta oscillations are evoked while gamma oscillations are induced. Odors strongly affect beta in PCx but have minimal (duration but not amplitude) effects on gamma. Unlike gamma, strong, odor-evoked beta oscillations are observed in TeLC. Using PCA, the authors found a small subset of neurons that conveyed most of …

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The authors used data from extracellular recordings in mouse piriform cortex (PCx) by Bolding & Franks (2018), they examined the strength, timing, and coherence of gamma oscillations with respiration in awake mice. During "spontaneous" activity (i.e. without odor or light stimulation), they observed a large peak in gamma that was driven by respiration and aligned with the spiking of FBIs. TeLC, which blocks synaptic output from principal cells onto other principal cells and FBIs, abolishes gamma. Beta oscillations are evoked while gamma oscillations are induced. Odors strongly affect beta in PCx but have minimal (duration but not amplitude) effects on gamma. Unlike gamma, strong, odor-evoked beta oscillations are observed in TeLC. Using PCA, the authors found a small subset of neurons that conveyed most of the information about the odor (winner cells). Loser cells were more phase-locked to gamma, which matched the time course of inhibition. Odor decoding accuracy closely follows the time course of gamma power.

I think this is an interesting study that uses a publicly available dataset to good effect and advances the field elegantly, especially by selectively analyzing activity in identified principal neurons versus inhibitory interneurons, and by making use of defined circuit perturbations to causally test some of their hypotheses.

Major:

- The authors show odor-specificity at the time of the gamma peak and imply that the gamma coupling is important for odor coding. Is this because gamma oscillations are important or because gamma is strongest when activity in PCx is strongest (i.e. both excitatory and inhibitory activity, which would cancel each other in the population PSTH, which peaks earlier)? To make this claim, the authors could show that odor decoding accuracy - with a small (~10 ms sliding window) - oscillates at approx. gamma frequencies. As is, Fig. 5 just shows that cells respond at slightly different times in the sniff cycle. What time window was used for computing the Odor Specificity Index? Put another way, is it meaningful that decoding is most accurate when gamma oscillations are strongest, or is this just a reflection of total population activity, i.e., when activity is greatest there is more gamma power, and odor decoding accuracy is best?

- The authors say, "assembly recruitment would depend on excitatory-excitatory interactions among winner cells occurring simultaneously during gamma activity." Can the authors test this prediction by examining the TeLC recordings, in which excitatory-excitatory connections are abolished?

- The authors show that gamma oscillations are abolished in the TeLC condition and use this to claim that gamma arises in the PCx. However, PCx neurons also project back to the OB, where they form excitatory connections onto granule cells. Fukunaga et al (2012) showed that granule cells are essential for generating gamma oscillations in the bulb. Can the authors be sure that gamma is generated in the PCx, per se, rather than generated in the bulb by centrifugal inputs from the PCx, and then inherited from the bulb by the PCx?

-

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

This is a very interesting paper, in which the authors describe how respiration-driven gamma oscillations in the piriform cortex are generated. Using a published data set, they find evidence for a feedback loop between local principal cells and feedback interneurons (FBIs) as the main driver of respiration-driven gamma. Interestingly, odour-evoked gamma bursts coincide with the emergence of neuronal assemblies that activate when a given odour is presented. The results argue in favour of a winner-take-all mechanism of assembly generation that has previously been suggested on theoretical grounds.

The article is well-written and the claims are justified by the data. Overall, the manuscript provides novel key insights into the generation of gamma oscillations and a potential link to the encoding of sensory input …

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

This is a very interesting paper, in which the authors describe how respiration-driven gamma oscillations in the piriform cortex are generated. Using a published data set, they find evidence for a feedback loop between local principal cells and feedback interneurons (FBIs) as the main driver of respiration-driven gamma. Interestingly, odour-evoked gamma bursts coincide with the emergence of neuronal assemblies that activate when a given odour is presented. The results argue in favour of a winner-take-all mechanism of assembly generation that has previously been suggested on theoretical grounds.

The article is well-written and the claims are justified by the data. Overall, the manuscript provides novel key insights into the generation of gamma oscillations and a potential link to the encoding of sensory input by cell assemblies. I have only minor suggestions for additional analyses that could further strengthen the manuscript:

1. The authors' analysis of firing rates of FFIs and FBIs combined with TeLC experiments make a compelling case for respiration-driven gamma being generated in a pyramidal cell-FBI feedback mechanism. This conclusion could be further strengthened by analyzing the gamma phase-coupling of the three neuronal populations investigated. One would expect strong coupling for FBIs but not FFIs (assuming that enough spikes of these populations could be sampled during the respiration-triggered gamma bursts). An additional analysis to strengthen this conclusion could be to extract FBI- and FFI spike-triggered gamma-filtered signals. One might expect an increase in gamma amplitude following FBI but not FFI spiking (see e.g., Pubmed ID 26890123).

2. The authors utilize the neurons' weight in the first PC to assign them to odour-related assemblies. This method convincingly extracts an assembly for each odour (when odours are used individually), and these seem to be virtually non-overlapping. It would be informative to test whether a similar clear separation of the individual assemblies could be achieved by running the analysis on all odours simultaneously, perhaps by employing a procedure of assembly extraction that allows to deal with overlapping assembly membership better than a pure PCA approach (as used for instance in the work cited on page 11, including the authors' previous work)? I do not doubt the validity of the authors' approach here at all, but the suggested additional analysis might allow the authors to increase their confidence that individual neurons contribute mostly to an assembly related to a single odour.

3. Do the authors observe a slow drift in assembly membership as predicted from previous work showing slowly changing odour responses of principal neurons (Schoonover et al., 2021)? This could perhaps be quantified by looking at the expression strengths of assemblies at individual odour presentations or by running the PCA separately on the first and last third of the odour presentations to test whether the same neurons are still 'winners'.

4. Does the winner-take-all scenario involve the recruitment of specific sets of FBIs during the activation of the individual odour-selective assemblies? The authors could address this by testing whether the rate of FBIs changes differently with the activation of the extracted assemblies.

5. Given the dependence on local gamma oscillations, one might expect that odour-selective assemblies do not emerge in the TeLC-expressing hemisphere. This could be directly tested in the existing data set.

-