Fitness advantage of Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron capsular polysaccharide in the mouse gut depends on the resident microbiota

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

eLife assessment

This study addresses whether the composition of the microbiota influences the intestinal colonization of encapsulated vs unencapsulated Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, a resident micro-organism of the colon. This is an important question because factors determining the colonization of gut bacteria remain a critical barrier in translating microbiome research into new bacterial cell-based therapies. To answer the question, the authors develop an innovative method to quantify B. theta population bottlenecks during intestinal colonization in the setting of different microbiota. Their main finding that the colonization defect of an acapsular mutant is dependent on the composition of the microbiota is valuable and this observation suggests that interactions between gut bacteria explains why the mutant has a colonization defect. The evidence supporting this claim is currently insufficient. Additionally, some of the analyses and claims are compromised because the authors do not fully explain their data and the number of animals is sometimes very small.

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

Many microbiota-based therapeutics rely on our ability to introduce a microbe of choice into an already-colonized intestine. In this study, we used genetically barcoded Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron ( B. theta ) strains to quantify population bottlenecks experienced by a B. theta population during colonization of the mouse gut. As expected, this reveals an inverse relationship between microbiota complexity and the probability that an individual wildtype B. theta clone will colonize the gut. The polysaccharide capsule of B. theta is important for resistance against attacks from other bacteria, phage, and the host immune system, and correspondingly acapsular B. theta loses in competitive colonization against the wildtype strain. Surprisingly, the acapsular strain did not show a colonization defect in mice with a low-complexity microbiota, as we found that acapsular strains have an indistinguishable colonization probability to the wildtype strain on single-strain colonization. This discrepancy could be resolved by tracking in vivo growth dynamics of both strains: acapsular B.theta shows a longer lag phase in the gut lumen as well as a slightly slower net growth rate. Therefore, as long as there is no niche competitor for the acapsular strain, this has only a small influence on colonization probability. However, the presence of a strong niche competitor (i.e., wildtype B. theta , SPF microbiota) rapidly excludes the acapsular strain during competitive colonization. Correspondingly, the acapsular strain shows a similarly low colonization probability in the context of a co-colonization with the wildtype strain or a complete microbiota. In summary, neutral tagging and detailed analysis of bacterial growth kinetics can therefore quantify the mechanisms of colonization resistance in differently-colonized animals.

Article activity feed

-

-

Author Response

eLife assessment:

This study addresses whether the composition of the microbiota influences the intestinal colonization of encapsulated vs unencapsulated Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, a resident micro-organism of the colon. This is an important question because factors determining the colonization of gut bacteria remain a critical barrier in translating microbiome research into new bacterial cell-based therapies. To answer the question, the authors develop an innovative method to quantify B. theta population bottlenecks during intestinal colonization in the setting of different microbiota. Their main finding that the colonization defect of an acapsular mutant is dependent on the composition of the microbiota is valuable and this observation suggests that interactions between gut bacteria explains why the mutant has a …

Author Response

eLife assessment:

This study addresses whether the composition of the microbiota influences the intestinal colonization of encapsulated vs unencapsulated Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, a resident micro-organism of the colon. This is an important question because factors determining the colonization of gut bacteria remain a critical barrier in translating microbiome research into new bacterial cell-based therapies. To answer the question, the authors develop an innovative method to quantify B. theta population bottlenecks during intestinal colonization in the setting of different microbiota. Their main finding that the colonization defect of an acapsular mutant is dependent on the composition of the microbiota is valuable and this observation suggests that interactions between gut bacteria explains why the mutant has a colonization defect. The evidence supporting this claim is currently insufficient. Additionally, some of the analyses and claims are compromised because the authors do not fully explain their data and the number of animals is sometimes very small.

Thank you for this frank evaluation. Based on the Reviewers’ comments, the points raised have been addressed by improving the writing (apologies for insufficient clarity), and by the addition of data that to a large extent already existed or could be rapidly generated. In particularly the following data has been added:

Increase to n>=7 for all fecal time-course experiments

Microbiota composition analysis for all mouse lines used

Data elucidating mechanisms of SPF microbiome/ host immune mechanisms restriction of acapsular B. theta

Short- versus long-term recolonization of germ-free mice with a complete SPF microbiota and assessment of the effect on B. theta colonization probability.

Challenge of B. theta monocolonized mice with avirulent Salmonella to disentangle effects of the host inflammatory response from other potential explanations of the observations.

Details of all inocula used

- Resequencing of all barcoded strains

Additionally, we have improved the clarity of the text, particularly the methods section describing mathematical modeling in the main text. Major changes in the text and particularly those replying to reviewers comment have been highlighted here and in the manuscript.

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The study addresses an important question - how the composition of the microbiota influences the intestinal colonization of encapsulated vs unencapsulated B. theta, an important commensal organism. To answer the question, the authors develop a refurbished WITS with extended mathematical modeling to quantify B. theta population bottlenecks during intestinal colonization in the setting of different microbiota. Interestingly, they show that the colonization defect of an acapsular mutant is dependent on the composition of the microbiota, suggesting (but not proving) that interactions between gut bacteria, rather than with host immune mechanisms, explains why the mutant has a colonization defect. However, it is fairly difficult to evaluate some of the claims because experimental details are not easy to find and the number of animals is very small. Furthermore, some of the analyses and claims are compromised because the authors do not fully explain their data; for example, leaving out the zero values in Fig. 3 and not integrating the effect of bottlenecks into the resulting model, undermines the claim that the acapsular mutant has a longer in vivo lag phase.

We thank the reviewer for taking time to give this details critique of our work, and apologies that the experimental details were insufficiently explained. This criticism is well taken. Exact inoculum details for experiment are now present in each figure (or as a supplement when multiple inocula are included). Exact microbiome composition analysis for OligoMM12, LCM and SPF microbiota is now included in Figure 2 – Figure supplement 1.

Of course, the models could be expanded to include more factors, but I think this comment is rather based on the data being insufficiently clearly explained by us. There are no “zero values missing” from Fig. 3 – this is visible in the submitted raw data table (excel file Source Data 1), but the points are fully overlapped in the graph shown and therefore not easily discernable from one another. Time-points where no CFU were recovered were plotted at a detection limit of CFU (50 CFU/g) and are included in the curve-fitting. However, on re-examination we noticed that the curve fit was carried out on the raw-data and not the log-normalized data which resulted in over-weighting of the higher values. Re-fitting this data does not change the conclusions but provides a better fit. These experiments have now been repeated such that we now have >=7 animals in each group. This new data is presented in Fig. 3C and D and Fig. 3 Supplement 2.

Limitations:

- The experiments do not allow clear separation of effects derived from the microbiota composition and those that occur secondary to host development without a microbiota or with a different microbiota. Furthermore, the measured bottlenecks are very similar in LCM and Oligo mice, even though these microbiotas differ in complexity. Oligo-MM12 was originally developed and described to confer resistance to Salmonella colonization, suggesting that it should tighten the bottleneck. Overall, an add-back experiment demonstrating that conventionalizing germ-free mice imparts a similar bottleneck to SPF would strengthen the conclusions.

These are excellent suggestions and have been followed. Additional data is now presented in Figure 2 – figure supplement 8 showing short, versus long-term recolonization of germ-free mice with an SPF microbiota and recovering very similar values of beta, to our standard SPF mouse colony. These data demonstrate a larger total niche size for B. theta at 2 days post-colonization which normalizes by 2 weeks post-colonization. Independent of this, the colonization probability, is already equivalent to that observed in our SPF colony at day 2 post-colonization. Therefore, the mechanisms causing early clonal loss are very rapidly established on colonization of a germ-free mouse with an SPF microbiota. We have additionally demonstrated that SPF mice do not have detectable intestinal antibody titers specific for acapsular B. theta. (Figure 2 – figure supplement 7), such that this is unlikely to be part of the reason why acapsular B. theta struggles to colonize at all in the context of an SPF microbiota. Experiments were also carried to detect bacteriophage capable of inducing lysis of B. theta and acapsular B. theta from SPF mouse cecal content (Figure 2 – figure supplement 7). No lytic phage plaques were observed. However, plaque assays are not sensitive for detection of weakly lytic phage, or phage that may require expression of surface structures that are not induced in vitro. We can therefore conclude that the restrictive activity of the SPF microbiota is a) reconstituted very fast in germ-free mice, b) is very likely not related to the activity of intestinal IgA and c) cannot be attributed to a high abundance of strongly lytic bacteriophage. The simplest explanation is that a large fraction of the restriction is due to metabolic competition with a complex microbiota, but we cannot formally exclude other factors such as antimicrobial peptides or changes in intestinal physiology.

- It is often difficult to evaluate results because important parameters are not always given. Dose is a critical variable in bottleneck experiments, but it is not clear if total dose changes in Figure 2 or just the WITS dose? Total dose as well as n0 should be depicted in all figures.

We apologized for the lack of clarity in the figures. Have added panels depicting the exact inoculum for each figure legend (or a supplementary figure where many inocula were used). Additionally, the methods section describing how barcoded CFU were calculated has been rewritten and is hopefully now clearer.

- This is in part a methods paper but the method is not described clearly in the results, with important bits only found in a very difficult supplement. Is there a difference between colonization probability (beta) and inoculum size at which tags start to disappear? Can there be some culture-based validation of "colonization probability" as explained in the mathematics? Can the authors contrast the advantages/disadvantages of this system with other methods (e.g. sequencing-based approaches)? It seems like the numerator in the colonization probability equation has a very limited range (from 0.18-1.8), potentially limiting the sensitivity of this approach.

We apologized for the lack of clarity in the methods. This criticism is well taken, and we have re-written large sections of the methods in the main text to include all relevant detail currently buried in the extensive supplement.

On the question of the colonization probability and the inoculum size, we kept the inoculum size at 107 CFU/ mouse in all experiments (except those in Fig.4, where this is explicitly stated); only changing the fraction of spiked barcoded strains. We verified the accuracy of our barcode recovery rate by serial dilution over 5 logs (new figure added: Figure 1 – figure supplement 1). “The CFU of barcoded strains in the inoculum at which tags start to disappear” is by definition closely related to the colonization probability, as this value (n0) appears in the calculation. Note that this is not the total inoculum size – this is (unless otherwise stated in Fig. 4) kept constant at 107 CFU by diluting the barcoded B. theta with untagged B. theta. Again, this is now better explained in all figure legends and the main text.

We have added an experiment using peak-to-trough ratios in metagenomic sequencing to estimate the B. theta growth rate. This could be usefully employed for wildtype B. theta at a relatively early timepoint post-colonization where growth was rapid. However, this is a metagenomics-based technique that requires the examined strain to be present at an abundance of over 0.1-1% for accurate quantification such that we could not analyze the acapsular B. theta strain in cecum content at the same timepoint. These data have been added (Figure 3 – figure supplement 3). Note that the information gleaned from these techniques is different. PTR reveals relative growth rates at a specific time (if your strain is abundant enough), whereas neutral tagging reveals average population values over quite large time-windows. We believe that both approaches are valuable. A few sentences comparing the approaches have been added to the discussion.

The actual numerator is the fraction of lost tags, which is obtained from the total number of tags used across the experiment (number of mice times the number of tags lost) over the total number of tags (number of mice times the number of tags used). Very low tag recovery (less than one per mouse) starts to stray into very noisy data, while close to zero loss is also associated with a low-information-to-noise ratio. Therefore, the size of this numerator is necessarily constrained by us setting up the experiments to have close to optimal information recovery from the WITS abundance. Robustness of these analyses is provided by the high “n” of between 10 and 17 mice per group.

- Figure 3 and the associated model is confusing and does not support the idea that a longer lag-phase contributes to the fitness defect of acapsular B.theta in competitive colonization. Figure 3B clearly indicates that in competition acapsular B. theta experiences a restrictive bottleneck, i.e., in competition, less of the initial B. theta population is contributed by the acapsular inoculum. There is no need to appeal to lag-phase defects to explain the role of the capsule in vivo. The model in Figure 3D should depict the acapsular population with less cells after the bottleneck. In fact, the data in Figure 3E-F can be explained by the tighter bottleneck experienced by the acapsular mutant resulting in a smaller acapsular founding population. This idea can be seen in the data: the acapsular mutant shedding actually dips in the first 12-hours. This cannot be discerned in Figure 3E because mice with zero shedding were excluded from the analysis, leaving the data (and conclusion) of this experiment to be extrapolated from a single mouse.

We of course completely agree that this would be a correct conclusion if only the competitive colonization data is taken into account. However, we are also trying to understand the mechanisms at play generating this bottleneck and have investigated a range of hypotheses to explain the results, taking into account all of our data.

Hypothesis 1) Competition is due to increased killing prior to reaching the cecum and commencing growth: Note that the probability of colonization for single B. theta clones is very similar for OligoMM12 mouse single-colonization by the wildtype and acapsular strains. For this hypothesis to be the reason for outcompetition of the acapsular strain, it would be necessary that the presence of wildtype would increase the killing of acapsular B. theta in the stomach or small intestine. The bacteria are at low density at this stage and stomach acid/small intestinal secretions should be similar in all animals. Therefore, this explanation seems highly unlikely

Hypothesis 2) Competition between wildtype and acapsular B. theta occurs at the point of niche competition before commencing growth in the cecum (similar to the proposal of the reviewer). It is possible that the wildtype strain has a competitive advantage in colonizing physical niches (for example proximity to bacteria producing colicins). On the basis of the data, we cannot exclude this hypothesis completely and it is challenging to measure directly. However, from our in vivo growth-curve data we observe a similar delay in CFU arrival in the feces for acapsular B. theta on single colonization as in competition, suggesting that the presence of wildtype (i.e., initial niche competition) is not the cause of this delay. Rather it is an intrinsic property of the acapsular strain in vivo,

Hypothesis 3) Competition between wildtype and acapsular B. theta is mainly attributable to differences in growth kinetics in the gut lumen. To investigate growth kinetics, we carried our time-courses of fecal collection from OligoMM12 mice single-colonized with wildtype or acapsular B. theta, i.e., in a situation where we observe identical colonization probabilities for the two strains. These date, shown now in Figure 3 C and D and Figure 3 – figure supplement 2, show that also without competition, the CFU of acapsular B. theta appear later and with a lower net growth rate than the wildtype. As these single-colonizations do not show a measurable difference between the colonization probability for the two strains, it is not likely that the delayed appearance of acapsular B. theta in feces is due to increased killing (this would be clearly visible in the barcode loss for the single-colonizations). Rather the simplest explanation for this observation is a bona fide lag phase before growth commences in the cecum. Interestingly, using only the lower net growth rate (assumed to be a similar growth rate but increased clearance rate) produces a good fit for our data on both competitive index and colonization probability in competition (Figure 3, figure supplement 5). This is slightly improved by adding in the observed lag-phase (Figure 3). It is very difficult to experimentally manipulate the lag phase in order to directly test how much of an effect this has on our hypothesis and the contribution is therefore carefully described in the new text.

Please note that all data was plotted and used in fitting in Fig 3E, but “zero-shedding” is plotted at a detection limit and overlayed, making it look like only one point was present when in fact several were used. This was clear in the submitted raw data tables. To sure-up these observations we have repeated all time-courses and now have n>=7 mice per group.

- The conclusions from Figure 4 rely on assumptions not well-supported by the data. In the high fat diet experiment, a lower dose of WITS is required to conclude that the diet has no effect. Furthermore, the authors conclude that Salmonella restricts the B. theta population by causing inflammation, but do not demonstrate inflammation at their timepoint or disprove that the Salmonella population could cause the same effect in the absence of inflammation (through non-inflammatory direct or indirect interactions).

We of course agree that we would expect to see some loss of B. theta in HFD. However, for these experiments the inoculum was ~109 CFUs/100μL dose of untagged strain spiked with approximately 30 CFU of each tagged strain. Decreasing the number of each WITS below 30 CFU leads to very high variation in the starting inocula from mouse-to-mouse which massively complicates the analysis. To clarify this point, we have added in a detection-limit calculation showing that the neutral tagging technique is not very sensitive to population contractions of less than 10-fold, which is likely in line with what would be expected for a high-fat diet feeding in monocolonized mice for a short time-span.

This is a very good observation regarding our Salmonella infection data. We have now added the fecal lipocalin 2 values, as well as a group infected with a ssaV/invG double mutant of S. Typhimurium that does not cause clinical grade inflammation (“avirulent”). This shows 1) that the attenuated S. Typhimurium is causing intestinal inflammation in B. theta colonized mice and 2) that a major fraction of the population bottleneck can be attributed to inflammation. Interestingly, we do observe a slight bottleneck in the group infected with avirulent Salmonella which could be attributable either to direct toxicity/competition of Salmonella with B. theta or to mildly increased intestinal inflammation caused by this strain. As we cannot distinguish these effects, this is carefully discussed in the manuscript.

- Several of the experiments rely on very few mice/groups.

We have increased the n to over 5 per group in all experiments (most critically those shown in Fig 3, Supplement 5). See figure legends for specific number of mice per experiment.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

The goal of this study was to understand population bottlenecks during colonization in the context of different microbial communities. Capsular polysaccharide mutants, diet, and enteric infection were also used paired to short-term monitoring of overall colonization and the levels of specific strains. The major strength of this study is the innovative approach and the significance of the overall research area.

The first major limitation is the lack of clear and novel insight into the biology of B. theta or other gut bacterial species. The title is provocative, but the experiments as is do not definitively show that the microbiota controls the relative fitness of acapsular and wild-type strains or provide any mechanistic insights into why that would be the case. The data on diet and infection seem preliminary. Furthermore, many of the experiments conflict with prior literature (i.e., lack of fitness difference between acapsular and wild-type strain and lack of impact of diet) but satisfying explanations are not provided for the lack of reproducibility.

In line with suggestions from Reviewer 1, the paper has undergone quite extensive re-writing to better explain the data presented and its consequences. Additionally, we now explicitly comment on apparent discrepancies between our reported data and the literature – for example the colonization defect of acapsular B. theta is only published for competitive colonizations, where we also observe a fitness defect so there is no actual conflict. Additionally, we have calculated detection limits for the effect of high-fat diet and demonstrate that a 10-fold reduction in the effective population size would not be robustly detected with the neutral tagging technique such that we are probably just underpowered to detect small effects, and we believe it is important to point out the numerical limits of the technique we present here. Additionally for the Figure 4 experiments, we have added data on colonization/competition with an avirulent Salmonella challenge giving some mechanistic data on the role of inflammation in the B. theta bottleneck.

Another major limitation is the lack of data on the various background gut microbiotas used. eLife is a journal for a broad readership. As such, describing what microbes are in LCM, OligoMM, or SPF groups is important. The authors seem to assume that the gut microbiota will reflect prior studies without measuring it themselves.

All gnotobiotic lines are bred as gnotobiotic colonies in our isolator facility. This is now better explained in the methods section. Additionally, 16S sequencing of all microbiotas used in the paper has been added as Figure 2 – figure supplement 1.

I also did not follow the logic of concluding that any differences between SPF and the two other groups are due to microbial diversity, which is presumably just one of many differences. For example, the authors acknowledge that host immunity may be distinct. It is essential to profile the gut microbiota by 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing in all these experiments and to design experiments that more explicitly test the diversity hypotheses vs. alternatives like differences in the membership of each community or other host phenotypes.

This is an important point. We have carried out a number of experiments to potentially address some issues here.

- We carried out B. theta colonization experiments in germ-free mice that had been colonized by gavage of SPF feces either 1 day prior to colonization of 2 weeks prior to colonization. While the shorter pre-colonization allowed B. theta to colonize to a higher population density in the cecum, the colonization probability was already reduced to levels observed in our SPF colony in the short pre-colonization. Therefore, the factors limiting B. theta establishment in the cecum are already established 1-2 days post-colonization with an SPF microbiota (Figure 2 - figure supplement 8).

- We checked for the presence of secretory IgA capable of binding to the surface of live B. theta, compared to a positive control of a mouse orally vaccinated against B. theta. (Fig. 2, Supplement 7) and could find no evidence of specific IgA targeting B. theta in the intestinal lavages of our SPF mouse colony.

- We isolated bacteriophage from the intestine of SPF mice and used this to infect lawns of B. theta wildtype and acapsular in vitro. We could not detect and plaque-forming phage coming from the intestine of SPF mice (Figure 2 – figure supplement 7).

We can therefore exclude strongly lytic phage and host IgA as dominant driving mechanisms restricting B. theta colonization. It remains possible that rapidly upregulated host factors such as antimicrobial peptide secretion could play a role, but metabolic competition from the microbiota is also a very strong candidate hypothesis. The text regarding these experiments has been slightly rewritten to point out that colonization probability inversely correlates with microbiota complexity, and the mechanisms involved may involve both direct microbe-microbe interactions as well as host factors.

Given the prior work on the importance of capsule for phage, I was surprised that no efforts are taken to monitor phage levels in these experiments. Could B. theta phage be present in SPF mice, explaining the results? Alternatively, is the mucus layer distinct? Both could be readily monitored using established molecular/imaging methods.

See above: no plaque-forming phage could be recovered from the SPF mouse cecum content. The main replicative site that we have studied here, in mice, is the cecum which does not have true mucus layers in the same way as the distal colon and is upstream of the colon so is unlikely to be affected by colon geography. Rather mucus is well mixed with the cecum content and may behave as a dispersed nutrient source. There is for sure a higher availability of mucus in the gnotobiotic mice due to less competition for mucus degradation by other strains. However, this would be challenging to directly link to the B. theta colonization phenotype as Muc2-deficient mice develop intestinal inflammation.

The conclusion that the acapsular strain loses out due to a difference of lag phase seems highly speculative. More work would be needed to ensure that there is no difference in the initial bottleneck; for example, by monitoring the level of this strain in the proximal gut immediately after oral gavage.

This is an excellent suggestion and has been carried out. At 8h post-colonization with a high inoculum (allowing easy detection) there were identical low levels of B. theta in the upper and lower small intestine, but more B. theta wildtype than B. theta acapsular in the cecum and colon, consistent with commencement of growth for B. theta wildtype but not the acapsular strain at this timepoint. We have additionally repeated the single-colonization time-courses using our standard inoculum and can clearly see the delayed detection of acapsular B. theta in feces even in the single-colonization state when no increased bottleneck is observed. This can only be reasonably explained by a bona fide lag-phase extension for acapsular B. theta in vivo. These data also reveal and decreased net growth rate of acapsular B. theta. Interestingly, our model can be quite well-fitted to the data obtained both for competitive index and for colonization probability using only the difference in net growth rate. Adding the (clearly observed) extended lag-phase generates a model that is still consistent with our observations.

Another major limitation of this paper is the reliance on short timepoints (2-3 days post colonization). Data for B. theta levels over 2 weeks or longer is essential to put these values in context. For example, I was surprised that B. theta could invade the gut microbiota of SPF mice at all and wonder if the early time points reflect transient colonization.

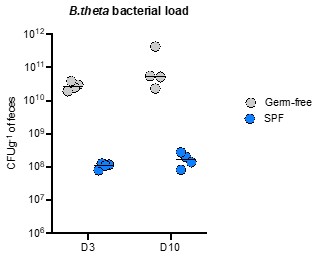

It should be noted that “SPF” defines microbiota only on missing pathogens and not on absolute composition. Therefore, the rather efficient B. theta colonization in our SPF colony is likely due to a permissive composition and this is likely to be not at all reproducible between different SPF colonies (a major confounder in reproducibility of mouse experiments between institutions. In contrast the gnotobiotic colonies are highly reproducible). We do consistently see colonization of our SPF colony by wildtype B. theta out to at least 10 days post-inoculation (latest time-point tested) at similar loads to the ones observed in this work, indicating that this is not just transient “flow-through” colonization. Data included below:

For this paper we were very specifically quantifying the early stages of colonization, also because the longer we run the experiments for, the more confounding features of our “neutrality” assumptions appear (e.g., host immunity selecting for evolved/phase-varied clones, within-host evolution of individual clones etc.). For this reason, we have used timepoints of a maximum of 2-3 days.

Finally, the number of mice/group is very low, especially given the novelty of these types of studies and uncertainty about reproducibility. Key experiments should be replicated at least once, ideally with more than n=3/group.

For all barcode quantification experiments we have between 10 and 17 mice per group. Experiments for the in vivo time-courses of colonization have been expanded to an “n” of at least 7 per group.

-

eLife assessment

This study addresses whether the composition of the microbiota influences the intestinal colonization of encapsulated vs unencapsulated Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, a resident micro-organism of the colon. This is an important question because factors determining the colonization of gut bacteria remain a critical barrier in translating microbiome research into new bacterial cell-based therapies. To answer the question, the authors develop an innovative method to quantify B. theta population bottlenecks during intestinal colonization in the setting of different microbiota. Their main finding that the colonization defect of an acapsular mutant is dependent on the composition of the microbiota is valuable and this observation suggests that interactions between gut bacteria explains why the mutant has a colonization defect. …

eLife assessment

This study addresses whether the composition of the microbiota influences the intestinal colonization of encapsulated vs unencapsulated Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, a resident micro-organism of the colon. This is an important question because factors determining the colonization of gut bacteria remain a critical barrier in translating microbiome research into new bacterial cell-based therapies. To answer the question, the authors develop an innovative method to quantify B. theta population bottlenecks during intestinal colonization in the setting of different microbiota. Their main finding that the colonization defect of an acapsular mutant is dependent on the composition of the microbiota is valuable and this observation suggests that interactions between gut bacteria explains why the mutant has a colonization defect. The evidence supporting this claim is currently insufficient. Additionally, some of the analyses and claims are compromised because the authors do not fully explain their data and the number of animals is sometimes very small.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The study addresses an important question - how the composition of the microbiota influences the intestinal colonization of encapsulated vs unencapsulated B. theta, an important commensal organism. To answer the question, the authors develop a refurbished WITS with extended mathematical modeling to quantify B. theta population bottlenecks during intestinal colonization in the setting of different microbiota. Interestingly, they show that the colonization defect of an acapsular mutant is dependent on the composition of the microbiota, suggesting (but not proving) that interactions between gut bacteria, rather than with host immune mechanisms, explains why the mutant has a colonization defect. However, it is fairly difficult to evaluate some of the claims because experimental details are not easy to find and …

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The study addresses an important question - how the composition of the microbiota influences the intestinal colonization of encapsulated vs unencapsulated B. theta, an important commensal organism. To answer the question, the authors develop a refurbished WITS with extended mathematical modeling to quantify B. theta population bottlenecks during intestinal colonization in the setting of different microbiota. Interestingly, they show that the colonization defect of an acapsular mutant is dependent on the composition of the microbiota, suggesting (but not proving) that interactions between gut bacteria, rather than with host immune mechanisms, explains why the mutant has a colonization defect. However, it is fairly difficult to evaluate some of the claims because experimental details are not easy to find and the number of animals is very small. Furthermore, some of the analyses and claims are compromised because the authors do not fully explain their data; for example, leaving out the zero values in Fig. 3 and not integrating the effect of bottlenecks into the resulting model, undermines the claim that the acapsular mutant has a longer in vivo lag phase.

Limitations:

1. The experiments do not allow clear separation of effects derived from the microbiota composition and those that occur secondary to host development without a microbiota or with a different microbiota. Furthermore, the measured bottlenecks are very similar in LCM and Oligo mice, even though these microbiotas differ in complexity. Oligo-MM12 was originally developed and described to confer resistance to Salmonella colonization, suggesting that it should tighten the bottleneck. Overall, an add-back experiment demonstrating that conventionalizing germ-free mice imparts a similar bottleneck to SPF would strengthen the conclusions.

2. It is often difficult to evaluate results because important parameters are not always given. Dose is a critical variable in bottleneck experiments, but it is not clear if total dose changes in Figure 2 or just the WITS dose? Total dose as well as n0 should be depicted in all figures.

3. This is in part a methods paper but the method is not described clearly in the results, with important bits only found in a very difficult supplement. Is there a difference between colonization probability (beta) and inoculum size at which tags start to disappear? Can there be some culture-based validation of "colonization probability" as explained in the mathematics? Can the authors contrast the advantages/disadvantages of this system with other methods (e.g. sequencing-based approaches)? It seems like the numerator in the colonization probability equation has a very limited range (from 0.18-1.8), potentially limiting the sensitivity of this approach.

4. Figure 3 and the associated model is confusing and does not support the idea that a longer lag-phase contributes to the fitness defect of acapsular B.theta in competitive colonization. Figure 3B clearly indicates that in competition acapsular B. theta experiences a restrictive bottleneck; i.e., in competition, less of the initial B. theta population is contributed by the acapsular inoculum. There is no need to appeal to lag-phase defects to explain the role of the capsule in vivo. The model in Figure 3D should depict the acapsular population with less cells after the bottleneck. In fact, the data in Figure 3E-F can be explained by the tighter bottleneck experienced by the acapsular mutant resulting in a smaller acapsular founding population. This idea can be seen in the data: the acapsular mutant shedding actually dips in the first 12-hours. This cannot be discerned in Figure 3E because mice with zero shedding were excluded from the analysis, leaving the data (and conclusion) of this experiment to be extrapolated from a single mouse.

5. The conclusions from Figure 4 rely on assumptions not well-supported by the data. In the high fat diet experiment, a lower dose of WITS is required to conclude that the diet has no effect. Furthermore, the authors conclude that Salmonella restricts the B. theta population by causing inflammation, but do not demonstrate inflammation at their timepoint or disprove that the Salmonella population could cause the same effect in the absence of inflammation (through non-inflammatory direct or indirect interactions).

6. Several of the experiments rely on very few mice/groups.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

The goal of this study was to understand population bottlenecks during colonization in the context of different microbial communities. Capsular polysaccharide mutants, diet, and enteric infection were also used paired to short-term monitoring of overall colonization and the levels of specific strains. The major strength of this study is the innovative approach and the significance of the overall research area.

The first major limitation is the lack of clear and novel insight into the biology of B. theta or other gut bacterial species. The title is provocative, but the experiments as is do not definitively show that the microbiota controls the relative fitness of acapsular and wild-type strains or provide any mechanistic insights into why that would be the case. The data on diet and infection seem …

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

The goal of this study was to understand population bottlenecks during colonization in the context of different microbial communities. Capsular polysaccharide mutants, diet, and enteric infection were also used paired to short-term monitoring of overall colonization and the levels of specific strains. The major strength of this study is the innovative approach and the significance of the overall research area.

The first major limitation is the lack of clear and novel insight into the biology of B. theta or other gut bacterial species. The title is provocative, but the experiments as is do not definitively show that the microbiota controls the relative fitness of acapsular and wild-type strains or provide any mechanistic insights into why that would be the case. The data on diet and infection seem preliminary. Furthermore, many of the experiments conflict with prior literature (i.e. lack of fitness difference between acapsular and wild-type strain and lack of impact of diet) but satisfying explanations are not provided for the lack of reproducibility.

Another major limitation is the lack of data on the various background gut microbiotas used. As such, describing what microbes are in LCM, OligoMM, or SPF groups is important. The authors seem to assume that the gut microbiota will reflect prior studies without measuring it themselves. I also did not follow the logic of concluding that any differences between SPF and the two other groups are due to microbial diversity, which is presumably just one of many differences. For example, the authors acknowledge that host immunity may be distinct. It is essential to profile the gut microbiota by 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing in all these experiments and to design experiments that more explicitly test the diversity hypotheses vs. alternatives like differences in the membership of each community or other host phenotypes.

Given the prior work on the importance of capsule for phage, I was surprised that no efforts are taken to monitor phage levels in these experiments. Could B. theta phage be present in SPF mice, explaining the results? Alternatively, is the mucus layer distinct? Both could be readily monitored using established molecular/imaging methods.

The conclusion that the acapsular strain loses out due to a difference of lag phase seems highly speculative. More work would be needed to ensure that there is no difference in the initial bottleneck; for example, by monitoring the level of this strain in the proximal gut immediately after oral gavage.

Another major limitation of this paper is the reliance on short timepoints (2-3 days post colonization). Data for B. theta levels over 2 weeks or longer is essential to put these values in context. For example, I was surprised that B. theta could invade the gut microbiota of SPF mice at all and wonder if the early time points reflect transient colonization.

Finally, the number of mice/group is very low, especially given the novelty of these types of studies and uncertainty about reproducibility. Key experiments should be replicated at least once, ideally with more than n=3/group.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

The manuscript by Hoces et al uses a small set of genetically barcoded B. theta strains to quantify population bottlenecks during colonization based on a Poisson model. They then estimate the decrease in niche size as a function of microbiota complexity. Although there was a surprising similarity between the WT and CPS mutant when colonizing separately, they showed that the competitive disadvantage during co-colonization was due to a lag before growth initiation in the gut. Overall, they make the interesting finding that capsule may be more important to deal with microbiota interactions rather than the host. In general, I find the manuscript well-constructed and interesting, using a clever method to understand an important question in microbiome biology. The titration experiments in particular led to very …

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

The manuscript by Hoces et al uses a small set of genetically barcoded B. theta strains to quantify population bottlenecks during colonization based on a Poisson model. They then estimate the decrease in niche size as a function of microbiota complexity. Although there was a surprising similarity between the WT and CPS mutant when colonizing separately, they showed that the competitive disadvantage during co-colonization was due to a lag before growth initiation in the gut. Overall, they make the interesting finding that capsule may be more important to deal with microbiota interactions rather than the host. In general, I find the manuscript well-constructed and interesting, using a clever method to understand an important question in microbiome biology. The titration experiments in particular led to very clean results.

-