Mandrill mothers associate with infants who look like their own offspring using phenotype matching

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

Evaluation Summary:

This article is of potential interest to researchers working on primate social behaviour, as it presents a novel mechanism for how an association with non-relatives can be favoured under kin selection. In a wild mandrill population, mothers are observed to preferentially lead offspring to associate with paternal half-sibs, a potential mechanism for encouraging nepotistic interactions between their offspring and other members of their group. The authors' explanation for their results was considered to be only partially supported by the data and a more measured and nuanced presentation would be appropriate.

(This preprint has been reviewed by eLife. We include the public reviews from the reviewers here; the authors also receive private feedback with suggested changes to the manuscript. Reviewer #3 agreed to share their name with the authors.)

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

Behavioral discrimination of kin is a key process structuring social relationships in animals. In this study, we provide evidence for discrimination towards non-kin by third-parties through a mechanism of phenotype matching. In mandrills, we recently demonstrated increased facial resemblance among paternally related juvenile and adult females indicating adaptive opportunities for paternal kin recognition. Here, we hypothesize that mandrill mothers use offspring’s facial resemblance with other infants to guide offspring’s social opportunities towards similar-looking ones. Using deep learning for face recognition in 80 wild mandrill infants, we first show that infants sired by the same father resemble each other the most, independently of their age, sex or maternal origin, extending previous results to the youngest age class. Using long-term behavioral observations on association patterns, and controlling for matrilineal origin, maternal relatedness and infant age and sex, we then show, as predicted, that mothers are spatially closer to infants that resemble their own offspring more, and that this maternal behavior leads to similar-looking infants being spatially associated. We then discuss the different scenarios explaining this result, arguing that an adaptive maternal behavior is a likely explanation. In support of this mechanism and using theoretical modeling, we finally describe a plausible evolutionary process whereby mothers gain fitness benefits by promoting nepotism among paternally related infants. This mechanism, that we call ‘second-order kin selection’, may extend beyond mother-infant interactions and has the potential to explain cooperative behaviors among non-kin in other social species, including humans.

Article activity feed

-

-

Author Response:

Reviewer #1:

Charpentier et al. use facial recognition technology to show that mothers in a group of mandrills lead their offspring to associate with phenotypically similar offspring. Mandrills are a species of primate that live in large, matrilineal troops, with a single, dominant male that fathers the majority of the offspring. Male breeder turnover and extra-pair mating by females can lead to variation in relatedness between group members and the potential for kin-selected benefits from preferentially cooperating with closer relatives within the group. The authors argue that the strategy of influencing the social network of their offspring could be favoured by "second-order kin selection", a mechanism by which inclusive fitness benefits are accrued to female actors through kin-selected benefits to their offspring. …

Author Response:

Reviewer #1:

Charpentier et al. use facial recognition technology to show that mothers in a group of mandrills lead their offspring to associate with phenotypically similar offspring. Mandrills are a species of primate that live in large, matrilineal troops, with a single, dominant male that fathers the majority of the offspring. Male breeder turnover and extra-pair mating by females can lead to variation in relatedness between group members and the potential for kin-selected benefits from preferentially cooperating with closer relatives within the group. The authors argue that the strategy of influencing the social network of their offspring could be favoured by "second-order kin selection", a mechanism by which inclusive fitness benefits are accrued to female actors through kin-selected benefits to their offspring. This interpretation is supported by a theoretical model.

The paper highlights a previously unappreciated mechanism for favouring association between non-kin in social groups and also contributes a nice insight into the complexity of social interactions in a relatively understudied wild primate species. The conclusions are strengthened by data showing associations between mothers were not influenced by the facial similarity of their offspring -- this suggests that mothers are making decisions based on the appearance of offspring and not their mothers.

Some remaining questions regarding the strength of the authors' interpretation exist: Given the challenges of studying mandrills in the field, the fact that the study reports data from a single group is understandable but potential issues remain with the independence of data points. There may be an additional issue arising from the fact that this troop is semi-captive.

The study group is not semi-captive. Instead, it originated from two release events of a few captive individuals into the wild (in 2002 and 2006). The population is now composed of more than 250 individuals and all of them, except for 7 founder females (<3%), were born in the wild. In addition, the study group is not fed and occasionally wanders into a fenced protected area. Fences of the park do not represent a boundary for mandrills and most of the time (c.a. 80% of days), the study group ranges outside the park. We have clarified this misunderstanding.

Regarding the independence of data points, we would be grateful if this reviewer could clarify her/his thoughts. As a tentative response, we indeed have access to a single (although large) study group, but that’s unfortunately often the case when studying primates or other large mammals. Regarding our study questions, we have clearly demonstrated increased nepotism among paternally related mandrills in two different social groups (Charpentier et al. 2007: semi-captive mandrills; Charpentier et al. 2020: wild mandrills). More generally, we do not see any parsimonious explanations for why the studied mandrills would behave or experienced selective pressures that may have differently shaped their genetic structure and social organization compared to other wild mandrill groups.

The number of genotyped offspring is relatively small (n = 15) and paternity is inferred from the identity of the dominant male. However, the authors also refer to the fact that it's normal for female mandrills to mate with several males during ovulation.

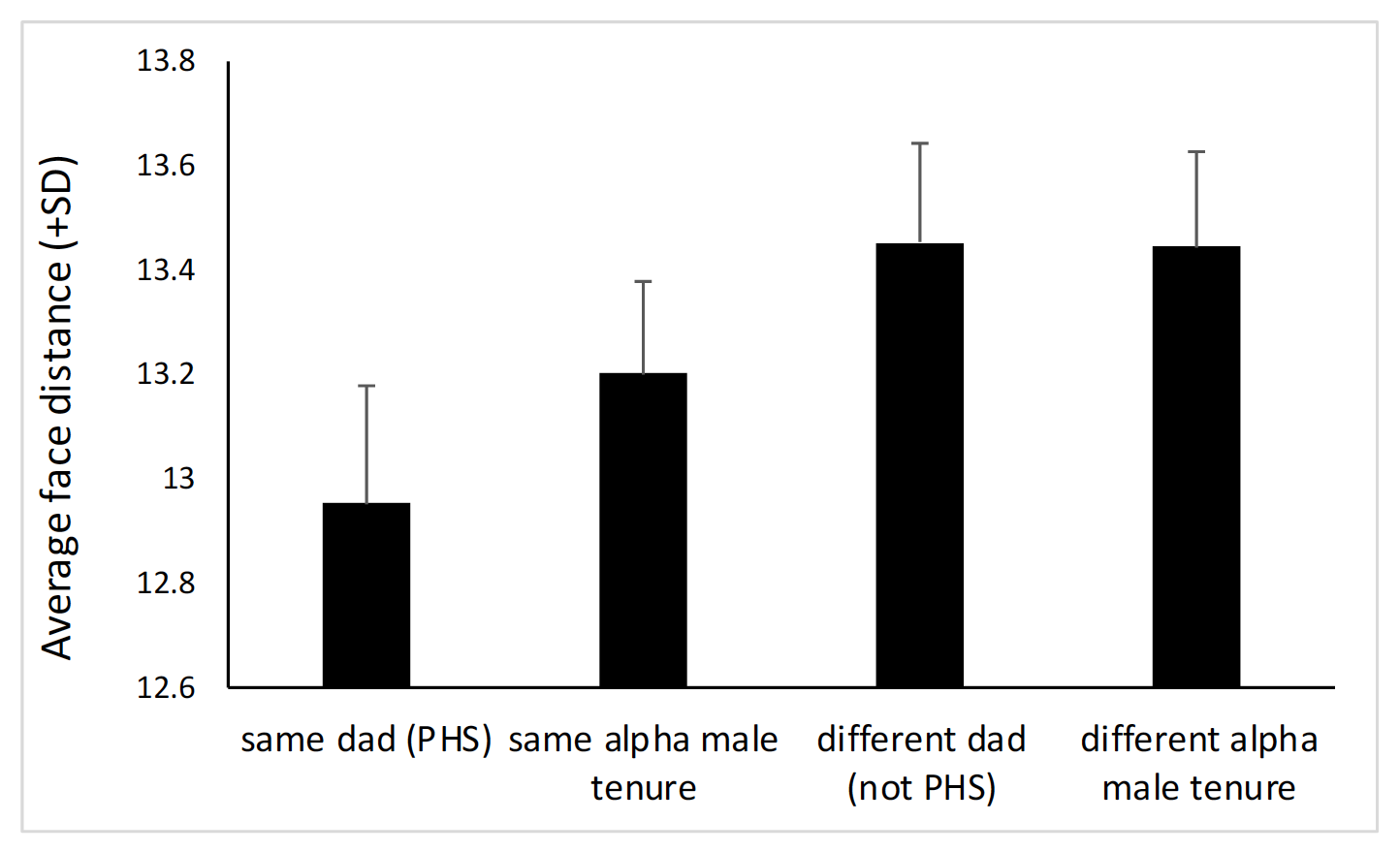

Indeed, both sexes mate promiscuously during the mating season. We have very recently (June 2022) obtained new genetic profiles for a subset of the study infants (it took two years to obtain these data). We have now increased our sample size of infants with a known father, from 15 to 32. With these new data, we were able to distinguish between four categories of infant-infant dyads: those sharing the same father (PHS), those not sharing the same father (not PHS), those conceived during the same alpha male tenure, and those that were not (both infants with unknown dads). The graph below shows the average facial distance among individuals for each of these four categories. It shows that infants conceived during the same alpha male tenure are significantly more similar to each other than infants sired by different fathers or during the tenure of different alpha males, but they are also significantly less similar to each other than infants born to the same father (the four categories are all significantly different from each other, except when comparing infants born to different fathers with those conceived during different alpha male tenures). As suggested by this reviewer, the fact that females mate predominantly with the alpha male, but to some extent also with other males, likely explains the difference between “same father” and “same alpha male tenure”. Importantly, however, considering all infants conceived during the same alpha male tenure as “PHS” is highly conservative. It is thus likely that knowing the paternity of every infant would produce even clearer effects (and indeed, increasing the data set from 15 to 32 strengthened this result). We have now updated this result (first model) based on this new sample.

What evidence is there to support a beneficial effect of nepotism in this species?

In mandrills, females who affiliate more (groom more/associate more) with their groupmates (kin or non-kin) during juvenility also reproduce 1 year earlier than those females that are poorly socially integrated (Charpentier et al. 2012). These results are similar to what is known in many mammalian species (see for review Snyder-Mackler et al. 2020). However, the positive effects of a rich social life are generally triggered by all group members, not only close kin. However, if beneficial social relationships impact the direct fitness of individuals, as reported in mandrills and other species, then kin selection theory predicts that these effects should further translate into indirect fitness benefits.

We have now added this relevant reference (Charpentier et al. 2012) in the revised version of our manuscript and present the results of this early study on mandrills.

What form could nepotism take and does it necessarily have to involve full sibs?

We are unsure why this reviewer is mentioning full-sibs here. For this reviewer information, on the 2556 study dyads (model 1 on the impact of maternal and paternal origins on facial distance), only one dyad was a full-sib pair. Full-sibs are therefore very rare in the study population due to male migration patterns and generally short alpha male tenures.

If a female did not associate with offspring as shown here, would nepotistic interactions simply arise between her offspring and offspring that were less facially similar?

We guess that facial similarity would not be a predictor of spatial association anymore. Indeed, we think that young mandrills do not use self-referent phenotype matching, precluding the self-evaluation of those infants that look like them. However, as stated below, we cannot fully exclude the possibility that other social partners, such as fathers, may also influence infant-infant relationships, although we think that this alternative mechanism is less parsimonious than the one we propose and test.

Reviewer #2:

This paper uses data on patterns of spatial association and facial similarity in mandrills to develop a new hypothesis for the evolution of kin recognition based on facial cues. Previous work on this system has shown that, among females, paternal half-sibs resemble each other visually more than maternal half-sisters do. The authors hypothesise that this paternally inherited facial similarity provides opportunities for kin selection, but it is unclear how offspring themselves could recognise kin using phenotype matching since they are unable to see their own face. One answer to this puzzle is that third parties -- mothers -- may promote social interactions between their own offspring and other offspring that resemble them since these other offspring are likely to share the same father. In support of this hypothesis, the authors find that mothers and offspring show spatial proximity to infants that are facially more similar than average. They also use an analytical evolutionary model to confirm the logic of this hypothesis. The model shows that mothers can gain inclusive fitness benefits by encouraging reciprocal social interaction among their offspring and other paternally-related offspring. They term this idea 'second-order' kin selection and identify a range of other circumstances in which it might play an important role in shaping the evolution of social behaviour.

The main strengths of the paper are the interesting mandrill data and the cutting-edge methods used to analyse facial similarity, which have stimulated the development of a theoretically interesting hypothesis about the evolution of facially based kin recognition. The theoretical model enhances the generality and rigour of the work. The paper will be of wide interest and the concept of second-order kin selection may be applicable to other social circumstances, such as interactions among in-laws in close-knit family groups. Thus, I can see that this paper will be a stimulus for future work.

We are grateful for these positive comments.

The data are, I think, rather overinterpreted in terms of the degree to which they support the hypothesis. The spatial proximity data are interesting, but on their own, they are not definitive support for the hypothesis or model. A more critical approach to the hypothesis, clearly setting out the limitations of the data, and what tests in future could be used to falsify the hypothesis or model, would make for a stronger paper.

We agree with this general comment and have addressed it by 1. Adding a model on grooming relationships between females and infants, 2. Toning down our interpretation throughout the manuscript and 3. Propose future directions of research.

Overall the authors have presented data that support a fascinating new mechanism by which natural selection can influence social interactions among the members of family groups, in potentially surprising ways. I also find it remarkable that 60 years after the development of the kin selection theory new implications of this theory are still being uncovered. The concept of second-order kin selection may prove important in understanding the evolution of social organisation and behaviour in species that live in groups containing a mixture of kin and non-kin, such as many primates and of course humans.

We are grateful to this reviewer for this very positive comment. We fully agree with the fact that 60 years after the kin selection theory has emerged, we are still discovering further implications!

Reviewer #3:

This is a very interesting and impressive manuscript. It is complex in its multiple components, and in some ways that makes it a difficult manuscript to evaluate. There is a lot in it, including empirical analyses of a face dataset and of behavioral association data, combined with a theoretical model.

We are very grateful for this positive comment and are glad that you liked our manuscript.

The three main findings are: 1) Paternal siblings look alike (similar to, and building on, a recent manuscript the authors published elsewhere); 2) Infants that are more facially similar tend to associate; and 3) mothers tend to be found in association with other unrelated infants that look more like their own infants. Such results are interesting, and indeed one potential interpretation, perhaps even the most likely, is that mothers are behaving in such a way that promotes association between their own infants and the paternal kin of their infants.

Nonetheless, the evidence provided is logically only consistent with the authors' hypothesis, rather than being strong direct evidence for it. As such, the current framing and indeed the title, "Primate mothers promote proximity between their offspring and infants who look like them", are both problematic. (In addition, the title should be about mandrills, not "primates", since this manuscript does not provide evidence from any other species.) The evidence provided is consistent with the hypothesis, but also consistent with other potential hypotheses. The evidence given to dismiss other potential hypotheses is not strong, and rests on the fact that many males are not around all year to influence things, and that "males that were present during a given reproductive cycle are not responsible for maintaining proximity with either infants or their mothers (MJEC and BRT, pers. obs.)".

We agree with this comment. Although, after examining several alternative mechanisms, in the light of the natural history of mandrills we are confident that the proposed mechanism is at work in that species, although we cannot firmly exclude some of these alternative mechanisms. To address this comment, we have changed the title of our manuscript that now reads “Mandrill mothers associate with infants who look like their own offspring using phenotype matching”. We have also included an additional model on grooming relationships (see response to R1) and have toned down the interpretation of our results throughout our revised manuscript. Finally, we have further discussed alternative scenario, in particular the one involving fathers (see details above).

My opinion is that these are really interesting analyses and data, which are being somewhat undermined by the insistence that only one hypothesis can explain the observed association patterns. It could easily be presented differently, as a demonstration that paternal siblings look alike and that they associate. The authors could then go on to explore different possible explanations for this using their association data, make the case that maternal behavior is the most plausible (but not the only) explanation, and present their model of how such behavior could bring fitness benefits.

In my view, such a presentation would be both more cautious and more appropriate, without in any way reducing the impact or importance of the data. In the current iteration, I think there are issues because the data do not provide sufficient support for the surety of the title and conclusion, as presented.

We think that the current organization of our manuscript was not that different from the one proposed here and follows a reasoning already proposed in a former manuscript (Charpentier et al. 2020). Indeed, we first start by reminding the reader what we already know from that previous studies: paternal siblings look alike and they associate. We then go on exploring different mechanisms. That being said, and as suggested, we have been more cautious in interpreting our results, that are indeed only correlative.

-

Evaluation Summary:

This article is of potential interest to researchers working on primate social behaviour, as it presents a novel mechanism for how an association with non-relatives can be favoured under kin selection. In a wild mandrill population, mothers are observed to preferentially lead offspring to associate with paternal half-sibs, a potential mechanism for encouraging nepotistic interactions between their offspring and other members of their group. The authors' explanation for their results was considered to be only partially supported by the data and a more measured and nuanced presentation would be appropriate.

(This preprint has been reviewed by eLife. We include the public reviews from the reviewers here; the authors also receive private feedback with suggested changes to the manuscript. Reviewer #3 agreed to share their …

Evaluation Summary:

This article is of potential interest to researchers working on primate social behaviour, as it presents a novel mechanism for how an association with non-relatives can be favoured under kin selection. In a wild mandrill population, mothers are observed to preferentially lead offspring to associate with paternal half-sibs, a potential mechanism for encouraging nepotistic interactions between their offspring and other members of their group. The authors' explanation for their results was considered to be only partially supported by the data and a more measured and nuanced presentation would be appropriate.

(This preprint has been reviewed by eLife. We include the public reviews from the reviewers here; the authors also receive private feedback with suggested changes to the manuscript. Reviewer #3 agreed to share their name with the authors.)

-

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Charpentier et al. use facial recognition technology to show that mothers in a group of mandrills lead their offspring to associate with phenotypically similar offspring. Mandrills are a species of primate that live in large, matrilineal troops, with a single, dominant male that fathers the majority of the offspring. Male breeder turnover and extra-pair mating by females can lead to variation in relatedness between group members and the potential for kin-selected benefits from preferentially cooperating with closer relatives within the group. The authors argue that the strategy of influencing the social network of their offspring could be favoured by "second-order kin selection", a mechanism by which inclusive fitness benefits are accrued to female actors through kin-selected benefits to their offspring. …

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Charpentier et al. use facial recognition technology to show that mothers in a group of mandrills lead their offspring to associate with phenotypically similar offspring. Mandrills are a species of primate that live in large, matrilineal troops, with a single, dominant male that fathers the majority of the offspring. Male breeder turnover and extra-pair mating by females can lead to variation in relatedness between group members and the potential for kin-selected benefits from preferentially cooperating with closer relatives within the group. The authors argue that the strategy of influencing the social network of their offspring could be favoured by "second-order kin selection", a mechanism by which inclusive fitness benefits are accrued to female actors through kin-selected benefits to their offspring. This interpretation is supported by a theoretical model.

The paper highlights a previously unappreciated mechanism for favouring association between non-kin in social groups and also contributes a nice insight into the complexity of social interactions in a relatively understudied wild primate species. The conclusions are strengthened by data showing associations between mothers were not influenced by the facial similarity of their offspring -- this suggests that mothers are making decisions based on the appearance of offspring and not their mothers.

Some remaining questions regarding the strength of the authors' interpretation exist:

Given the challenges of studying mandrills in the field, the fact that the study reports data from a single group is understandable but potential issues remain with the independence of data points. There may be an additional issue arising from the fact that this troop is semi-captive.The number of genotyped offspring is relatively small (n = 15) and paternity is inferred from the identity of the dominant male. However, the authors also refer to the fact that it's normal for female mandrills to mate with several males during ovulation.

What evidence is there to support a beneficial effect of nepotism in this species? What form could nepotism take and does it necessarily have to involve full sibs? If a female did not associate with offspring as shown here, would nepotistic interactions simply arise between her offspring and offspring that were less facially similar?

-

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

This paper uses data on patterns of spatial association and facial similarity in mandrills to develop a new hypothesis for the evolution of kin recognition based on facial cues. Previous work on this system has shown that, among females, paternal half-sibs resemble each other visually more than maternal half-sisters do. The authors hypothesise that this paternally inherited facial similarity provides opportunities for kin selection, but it is unclear how offspring themselves could recognise kin using phenotype matching since they are unable to see their own face. One answer to this puzzle is that third parties -- mothers -- may promote social interactions between their own offspring and other offspring that resemble them since these other offspring are likely to share the same father. In support of this …

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

This paper uses data on patterns of spatial association and facial similarity in mandrills to develop a new hypothesis for the evolution of kin recognition based on facial cues. Previous work on this system has shown that, among females, paternal half-sibs resemble each other visually more than maternal half-sisters do. The authors hypothesise that this paternally inherited facial similarity provides opportunities for kin selection, but it is unclear how offspring themselves could recognise kin using phenotype matching since they are unable to see their own face. One answer to this puzzle is that third parties -- mothers -- may promote social interactions between their own offspring and other offspring that resemble them since these other offspring are likely to share the same father. In support of this hypothesis, the authors find that mothers and offspring show spatial proximity to infants that are facially more similar than average. They also use an analytical evolutionary model to confirm the logic of this hypothesis. The model shows that mothers can gain inclusive fitness benefits by encouraging reciprocal social interaction among their offspring and other paternally-related offspring. They term this idea 'second-order' kin selection and identify a range of other circumstances in which it might play an important role in shaping the evolution of social behaviour.

The main strengths of the paper are the interesting mandrill data and the cutting-edge methods used to analyse facial similarity, which have stimulated the development of a theoretically interesting hypothesis about the evolution of facially based kin recognition. The theoretical model enhances the generality and rigour of the work. The paper will be of wide interest and the concept of second-order kin selection may be applicable to other social circumstances, such as interactions among in-laws in close-knit family groups. Thus, I can see that this paper will be a stimulus for future work.

The data are, I think, rather overinterpreted in terms of the degree to which they support the hypothesis. The spatial proximity data are interesting, but on their own, they are not definitive support for the hypothesis or model. A more critical approach to the hypothesis, clearly setting out the limitations of the data, and what tests in future could be used to falsify the hypothesis or model, would make for a stronger paper.

Overall the authors have presented data that support a fascinating new mechanism by which natural selection can influence social interactions among the members of family groups, in potentially surprising ways. I also find it remarkable that 60 years after the development of the kin selection theory new implications of this theory are still being uncovered. The concept of second-order kin selection may prove important in understanding the evolution of social organisation and behaviour in species that live in groups containing a mixture of kin and non-kin, such as many primates and of course humans.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

This is a very interesting and impressive manuscript. It is complex in its multiple components, and in some ways that makes it a difficult manuscript to evaluate. There is a lot in it, including empirical analyses of a face dataset and of behavioral association data, combined with a theoretical model.

The three main findings are: 1) Paternal siblings look alike (similar to, and building on, a recent manuscript the authors published elsewhere); 2) Infants that are more facially similar tend to associate; and 3) mothers tend to be found in association with other unrelated infants that look more like their own infants. Such results are interesting, and indeed one potential interpretation, perhaps even the most likely, is that mothers are behaving in such a way that promotes association between their own infants …

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

This is a very interesting and impressive manuscript. It is complex in its multiple components, and in some ways that makes it a difficult manuscript to evaluate. There is a lot in it, including empirical analyses of a face dataset and of behavioral association data, combined with a theoretical model.

The three main findings are: 1) Paternal siblings look alike (similar to, and building on, a recent manuscript the authors published elsewhere); 2) Infants that are more facially similar tend to associate; and 3) mothers tend to be found in association with other unrelated infants that look more like their own infants. Such results are interesting, and indeed one potential interpretation, perhaps even the most likely, is that mothers are behaving in such a way that promotes association between their own infants and the paternal kin of their infants.

Nonetheless, the evidence provided is logically only consistent with the authors' hypothesis, rather than being strong direct evidence for it. As such, the current framing and indeed the title, "Primate mothers promote proximity between their offspring and infants who look like them", are both problematic. (In addition, the title should be about mandrills, not "primates", since this manuscript does not provide evidence from any other species.) The evidence provided is consistent with the hypothesis, but also consistent with other potential hypotheses. The evidence given to dismiss other potential hypotheses is not strong, and rests on the fact that many males are not around all year to influence things, and that "males that were present during a given reproductive cycle are not responsible for maintaining proximity with either infants or their mothers (MJEC and BRT, pers. obs.)".

My opinion is that these are really interesting analyses and data, which are being somewhat undermined by the insistence that only one hypothesis can explain the observed association patterns. It could easily be presented differently, as a demonstration that paternal siblings look alike and that they associate. The authors could then go on to explore different possible explanations for this using their association data, make the case that maternal behavior is the most plausible (but not the only) explanation, and present their model of how such behavior could bring fitness benefits.

In my view, such a presentation would be both more cautious and more appropriate, without in any way reducing the impact or importance of the data. In the current iteration, I think there are issues because the data do not provide sufficient support for the surety of the title and conclusion, as presented.

-