In silico design and validation of high-affinity RNA aptamers for SARS-CoV-2 comparable to neutralizing antibodies

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

eLife Assessment

This valuable study introduces CAAMO, a computational framework that combines structure prediction, in silico mutagenesis, molecular simulations, and energy calculations to design RNA aptamers with improved binding affinity. The computational methodology is solid, demonstrating strong theoretical foundations and systematic integration of multiple prediction techniques. However, the experimental validation is incomplete, with methodological weaknesses that limit the strength of support for the computational predictions.

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

Nucleic acid aptamers hold promise for clinical applications, yet understanding their molecular binding mechanisms to target proteins and efficiently optimizing their binding affinities remain challenging. Here, we present CAAMO (Computer-Aided Aptamer Modeling and Optimization), which integrates in silico aptamer design with experimental validation to accelerate the development of aptamer-based RNA therapeutics. Starting from the sequence information of a reported RNA aptamer, Ta, for the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, our CAAMO method first determines its binding mode with the spike protein’s receptor binding domain (RBD) through a multi-strategy computational approach. We then optimize its binding affinity via structure-based rational design. Among the six designed candidates, five were experimentally verified and exhibited enhanced binding affinities compared to the original Ta sequence. Furthermore, we directly compared the binding properties of the RNA aptamers to neutralizing antibodies, and found that the designed aptamer TaG34C demonstrated a comparable binding affinity to the RBD compared to all tested neutralizing antibodies. This highlights its potential as an alternative to existing COVID-19 antibodies. Our work provides a robust approach for the efficient design of a relatively large number of high-affinity aptamers with complicated topologies. This approach paves the way for the development of aptamer-based RNA diagnostics and therapeutics.

Article activity feed

-

eLife Assessment

This valuable study introduces CAAMO, a computational framework that combines structure prediction, in silico mutagenesis, molecular simulations, and energy calculations to design RNA aptamers with improved binding affinity. The computational methodology is solid, demonstrating strong theoretical foundations and systematic integration of multiple prediction techniques. However, the experimental validation is incomplete, with methodological weaknesses that limit the strength of support for the computational predictions.

-

Reviewer #4 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors demonstrate a computational rational design approach for developing RNA aptamers with improved binding to the Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. They demonstrate the ability of their approach to improve binding affinity using a previously identified RNA aptamer, RBD-PB6-Ta, which binds to the RBD. They also computationally estimate the binding energies of various RNA aptamers with the RBD and compare against RBD binding energies for a few neutralizing antibodies from the literature. Finally, experimental binding affinities are estimated by electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) for various RNA aptamers and a single commercially available neutralizing antibody to support the conclusions from computational studies on binding. The authors conclude that …

Reviewer #4 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors demonstrate a computational rational design approach for developing RNA aptamers with improved binding to the Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. They demonstrate the ability of their approach to improve binding affinity using a previously identified RNA aptamer, RBD-PB6-Ta, which binds to the RBD. They also computationally estimate the binding energies of various RNA aptamers with the RBD and compare against RBD binding energies for a few neutralizing antibodies from the literature. Finally, experimental binding affinities are estimated by electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) for various RNA aptamers and a single commercially available neutralizing antibody to support the conclusions from computational studies on binding. The authors conclude that their computational framework, CAAMO, can provide reliable structure predictions and effectively support rational design of improved affinity for RNA aptamers towards target proteins. Additionally, they claim that their approach achieved design of high affinity RNA aptamer variants that bind to the RBD as well or better than a commercially available neutralizing antibody.

Strengths:

The thorough computational approaches employed in the study provide solid evidence of the value of their approach for computational design of high affinity RNA aptamers. The theoretical analysis using Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) to estimate relative binding energies supports the claimed improvement of affinity for RNA aptamers and provides valuable insight into the binding model for the tested RNA aptamers in comparison to previously studied neutralizing antibodies. The multimodal structure prediction in the early stages of the presented CAAMO framework, combined with the demonstrated outcome of improved affinity using the structural predictions as a starting point for rational design, provide moderate confidence in the structure predictions.

Weaknesses:

The experimental characterization of RBD affinities for the antibody and RNA aptamers in this study present serious concerns regarding the methods used and the data presented in the manuscript, which call into question the major conclusions regarding affinity towards the RBD for their aptamers compared to antibodies. The claim that structural predictions from CAAMO are reasonable is rational, but this claim would be significantly strengthened by experimental validation of the structure (i.e. by chemical footprinting or solving the RBD-aptamer complex structure).

The conclusions in this work are somewhat supported by the data, but there are significant issues with experimental methods that limit the strength of the study's conclusions.

(1) The EMSA experiments have a number of flaws that limit their interpretability. The uncropped electrophoresis images, which should include molecular size markers and/or positive and negative controls for bound and unbound complex components to support interpretation of mobility shifts, are not presented. In fact, a spliced image can be seen for Figure 4E, which limits interpretation without the full uncropped image. Additionally, he volumes of EMSA mixtures are not presented when a mass is stated (i.e. for the methods used to create Figure 3D), which leaves the reader without the critical parameter, molar concentration, and therefore leaves in question the claim that the tested antibody is high affinity under the tested conditions. Additionally, protein should be visualized in all gels as a control to ensure that lack of shifts is not due to absence/aggregation/degradation of the RBD protein. In the case of Figure 3E, for example, it can be seen that there are degradation products included in the RBD-only lane, introducing a reasonable doubt that the lack of a shift in RNA tests (i.e. Figure 2F) is conclusively due to a lack of binding. Finally, there is no control for nonspecific binding, such as BSA or another non-target protein, which fails to eliminate the possibility of nonspecific interactions between their designed aptamers and proteins in general. A nonspecific binding control should be included in all EMSA experiments.

(2) The evidence supporting claims of better binding to RBD by the aptamer compared to the commercial antibody is flawed at best. The commercial antibody product page indicates an affinity in low nanomolar range, whereas the fitted values they found for the aptamers in their study are orders of magnitude higher at tens of micromolar. Moreover, the methods section is lacking in the details required to appropriately interpret the competitive binding experiments. With a relatively short 20-minute equilibration time, the order of when the aptamer is added versus the antibody makes a difference in which is apparently bound. The issue with this becomes apparent with the lack of internal consistency in the presented results, namely in comparing Fig 3E (which shows no interference of Ta binding with 5uM antibody) and Fig 5D (which shows interference of Ta binding with 0.67-1.67uM antibody). The discrepancy between these figures calls into question the methods used, and it necessitates more details regarding experimental methods used in this manuscript.

(3) The utility of the approach for increasing affinity of RNA aptamers for their targets is well supported through computational and experimental techniques demonstrating relative improvements in binding affinity for their G34C variant compared to the starting Ta aptamer. While the EMSA experiments do have significant flaws, the observations of relative relationships in equilibrium binding affinities among the tested aptamer variants can be interpreted with reasonable confidence, given that they were all performed in a consistent manner.

(4) The claim that the structure of the RBD-Aptamer complex predicted by the CAAMO pipeline is reliable is tenuous. The success of their rational design approach based on the structure predicted by several ensemble approaches supports the interpretation of the predicted structure as reasonable, however, no experimental validation is undertaken to assess the accuracy of the structure. This is not a main focus of the manuscript, given the applied nature of the study to identify Ta variants with improved binding affinity, however the structural accuracy claim is not strongly supported without experimental validation (i.e. chemical footprinting methods).

(5) Throughout the manuscript, the phrasing of "all tested antibodies" was used, despite there being only one tested antibody in experimental methods and three distinct antibodies in computational methods. While this concern is focused on specific language, the major conclusion that their designed aptamers are as good or better than neutralizing antibodies in general is weakened by only testing only three antibodies through computational binding measurements and a fourth single antibody for experimental testing. The contact residue mapping furthermore lacks clarity in the number of structures that were used, with a vague description of structures from the PDB including no accession numbers provided nor how many distinct antibodies were included for contact residue mapping.

Overall, the manuscript by Yang et al presents a valuable tool for rational design of improved RNA aptamer binding affinity toward target proteins, which the authors call CAAMO. Notably, the method is not intended for de novo design, but rather as a tool for improving aptamers that have been selected for binding affinity by other methods such as SELEX. While there are significant issues in the conclusions made from experiments in this manuscript, the relative relationships of observed affinities within this study provide solid evidence that the CAAMO framework provides a valuable tool for researchers seeking to use rational design approaches for RNA aptamer affinity maturation.

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the current reviews.

Reviewer #4 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors demonstrate a computational rational design approach for developing RNA aptamers with improved binding to the Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. They demonstrate the ability of their approach to improve binding affinity using a previously identified RNA aptamer, RBD-PB6-Ta, which binds to the RBD. They also computationally estimate the binding energies of various RNA aptamers with the RBD and compare against RBD binding energies for a few neutralizing antibodies from the literature. Finally, experimental binding affinities are estimated by electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) for various RNA aptamers and a single commercially available neutralizing antibody to support the …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the current reviews.

Reviewer #4 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors demonstrate a computational rational design approach for developing RNA aptamers with improved binding to the Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. They demonstrate the ability of their approach to improve binding affinity using a previously identified RNA aptamer, RBD-PB6-Ta, which binds to the RBD. They also computationally estimate the binding energies of various RNA aptamers with the RBD and compare against RBD binding energies for a few neutralizing antibodies from the literature. Finally, experimental binding affinities are estimated by electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) for various RNA aptamers and a single commercially available neutralizing antibody to support the conclusions from computational studies on binding. The authors conclude that their computational framework, CAAMO, can provide reliable structure predictions and effectively support rational design of improved affinity for RNA aptamers towards target proteins. Additionally, they claim that their approach achieved design of high affinity RNA aptamer variants that bind to the RBD as well or better than a commercially available neutralizing antibody.

Strengths:

The thorough computational approaches employed in the study provide solid evidence of the value of their approach for computational design of high affinity RNA aptamers. The theoretical analysis using Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) to estimate relative binding energies supports the claimed improvement of affinity for RNA aptamers and provides valuable insight into the binding model for the tested RNA aptamers in comparison to previously studied neutralizing antibodies. The multimodal structure prediction in the early stages of the presented CAAMO framework, combined with the demonstrated outcome of improved affinity using the structural predictions as a starting point for rational design, provide moderate confidence in the structure predictions.

We thank the reviewer for this accurate summary and for recognizing the strength of our integrated computational–experimental workflow in improving aptamer affinity.

Weaknesses:

The experimental characterization of RBD affinities for the antibody and RNA aptamers in this study present serious concerns regarding the methods used and the data presented in the manuscript, which call into question the major conclusions regarding affinity towards the RBD for their aptamers compared to antibodies. The claim that structural predictions from CAAMO are reasonable is rational, but this claim would be significantly strengthened by experimental validation of the structure (i.e. by chemical footprinting or solving the RBD-aptamer complex structure).

The conclusions in this work are somewhat supported by the data, but there are significant issues with experimental methods that limit the strength of the study's conclusions.

(1) The EMSA experiments have a number of flaws that limit their interpretability. The uncropped electrophoresis images, which should include molecular size markers and/or positive and negative controls for bound and unbound complex components to support interpretation of mobility shifts, are not presented. In fact, a spliced image can be seen for Figure 4E, which limits interpretation without the full uncropped image.

Thank you for your valuable comments and careful review.

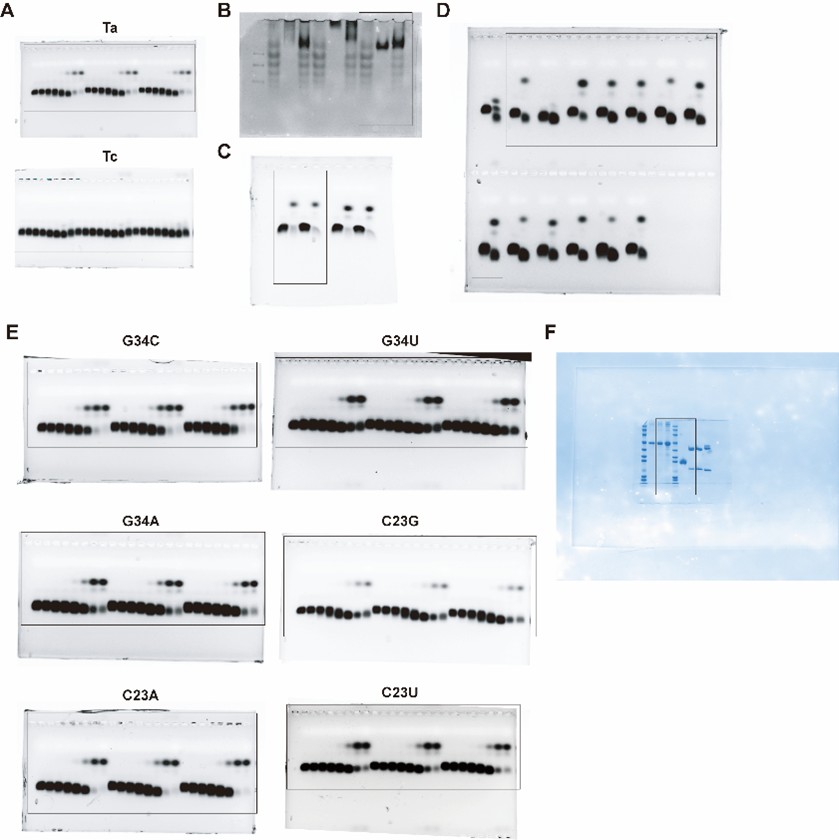

In response to your suggestion, we will provide all uncropped electrophoresis raw images corresponding to the results in the main figures and supplementary figures (Figure 2F, 3D, 3E, 4E, S9A and S10 of the original manuscript) in the revised version. Regarding the spliced image in Figure 4E, the uncropped raw gel image clearly shows that the two C23U samples were run on an adjacent lane of the same gel due to the total number of samples exceeding the well capacity of a single lane. All samples were electrophoresed and signal-detected under identical experimental conditions in one single experiment, ensuring the validity of direct signal intensity comparison across all samples. These complete uncropped raw images will be supplemented in the revised manuscript as Figure S12 (also see Author response image 1).

Author response image 1.

Uncropped electrophoresis images corresponding to Figures 2F, 3D, 3E, 4E, S9A and S10 of the original manuscript.

Additionally, he volumes of EMSA mixtures are not presented when a mass is stated (i.e. for the methods used to create Figure 3D), which leaves the reader without the critical parameter, molar concentration, and therefore leaves in question the claim that the tested antibody is high affinity under the tested conditions.

Thank you for your valuable comment on this oversight.

For the EMSA assay in Figure 3D, the reaction mixture (10 μL total volume) contained 3 μg of RBD protein and 3 μg of antibody (40592-R001), either individually or in combination, with incubation at room temperature for 20 minutes. Based on the molecular weights (35 kDa for RBD and 150 kDa for the IgG antibody), the corresponding molar concentrations in the mixture were calculated as 8.57 μM for RBD and 2 μM for the antibody. To ensure consistency, clarity and provide the critical molar concentration parameter, we will revise the legend of Figure 3D, replacing the mass values with the calculated molar concentrations as you suggested in the revised manuscript.

Additionally, protein should be visualized in all gels as a control to ensure that lack of shifts is not due to absence/aggregation/degradation of the RBD protein. In the case of Figure 3E, for example, it can be seen that there are degradation products included in the RBD-only lane, introducing a reasonable doubt that the lack of a shift in RNA tests (i.e. Figure 2F) is conclusively due to a lack of binding.

We sincerely appreciate your careful evaluation of our work, which helps us further clarify the experimental details and data reliability.

First, we would like to clarify the nature of the gel electrophoresis in Figure 3E: the RBD protein was separated by native-PAGE rather than denaturing SDS-PAGE. The RBD protein used in all experiments was purchased from HUABIO (Cat. No. HA210064) with guaranteed quality, and its integrity and purity were independently verified in our laboratory via denaturing SDS-PAGE (see Author response image 2), which showed a single, intact band without any degradation products. The ladder-like bands observed in the RBD-only lane of the native-PAGE gel are not a result of protein degradation. Instead, they arise from two well-characterized properties of recombinant SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD protein expressed in human cells: intrinsic conformational heterogeneity (the RBD domain exists in multiple dynamic conformations due to its structural flexibility) (Cai et al., Science, 2020; Wrapp et al., Science, 2020) and heterogeneity in N-glycosylation modification (variable glycosylation patterns at the conserved N-glycosylation sites of RBD) (Casalino et al., ACS Cent. Sci., 2020; Ives et al., eLife, 2024), both of which could cause distinct migration bands in native-PAGE under non-denaturing conditions.

Second, to ensure the reliability of the RNA-binding results, the EMSA experiments for determining the binding affinity (Kd) of RBD to Ta, Tc and Ta variants were performed with three independent biological replicates (the original manuscript includes all replicate data in Figure 2F and S9). Consistent results were obtained across all replicates, which effectively rules out false-negative outcomes caused by accidental absence or loss of functional RBD protein in the reaction system. In addition, our gel images (Figure 2F and S9 in the original manuscript) and uncropped raw images of all EMSA gels (see Author response image 1) show no significant signal accumulation in the sample wells, confirming the absence of RBD protein aggregation in the binding reactions—an issue that would otherwise interfere with RNA-protein interaction and band shift detection.

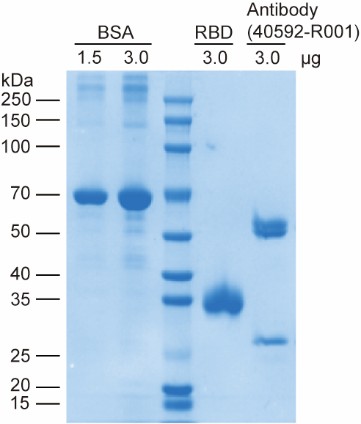

New results for RBD analysis by denaturing SDS-PAGE, along with the associated discussion, will be added to the revised manuscript as Figure S10 (also see Author response image 2).

Author response image 2.

SDS-PAGE analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD protein, neutralizing antibody (40592-R001) and BSA reference. This gel validates the high purity and structural integrity of the commercially sourced RBD protein and neutralizing antibody used in this study.

References

Cai, Y. et al. Distinct conformational states of SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins. Science 369, 1586-1592 (2020).

Casalino, L. et al. Beyond shielding: the roles of glycans in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. ACS Cent. Sci. 6, 1722-1734 (2020).

Ives, C.M. et al. Role of N343 glycosylation on the SARS-CoV-2 S RBD structure and co-receptor binding across variants of concern. eLife 13, RP95708 (2024).

Wrapp, D. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 367, 1260-1263 (2020).

Finally, there is no control for nonspecific binding, such as BSA or another non-target protein, which fails to eliminate the possibility of nonspecific interactions between their designed aptamers and proteins in general. A nonspecific binding control should be included in all EMSA experiments.

Thank you for this constructive comment.

Following your recommendation, we are currently supplementing the EMSA assays with BSA as a non-target protein control to rigorously exclude potential non-specific binding between our designed aptamers (Ta and Ta variants) and exogenous proteins. These additional experiments are designed to directly assess whether the aptamers exhibit unintended interactions with unrelated proteins and to further validate the protein specificity of the RBD–aptamer interaction observed in our study.

The resulting nonspecific binding control data will be formally incorporated into the revised manuscript as Figure S11, and the corresponding Results and Discussion sections will be updated accordingly to reflect this critical validation once the experiments are completed.

(2) The evidence supporting claims of better binding to RBD by the aptamer compared to the commercial antibody is flawed at best. The commercial antibody product page indicates an affinity in low nanomolar range, whereas the fitted values they found for the aptamers in their study are orders of magnitude higher at tens of micromolar. Moreover, the methods section is lacking in the details required to appropriately interpret the competitive binding experiments. With a relatively short 20-minute equilibration time, the order of when the aptamer is added versus the antibody makes a difference in which is apparently bound. The issue with this becomes apparent with the lack of internal consistency in the presented results, namely in comparing Fig 3E (which shows no interference of Ta binding with 5uM antibody) and Fig 5D (which shows interference of Ta binding with 0.67-1.67uM antibody). The discrepancy between these figures calls into question the methods used, and it necessitates more details regarding experimental methods used in this manuscript.

Thank you for your insightful comments, which have helped us refine the rigor of our study. We address each of your concerns in detail below:

First, we agree with your observation that the commercial neutralizing antibody (Sino Biological, Cat# 40592-R001) is reported to bind Spike RBD with low nanomolar affinity on its product page. However, this discrepancy in affinity values (nanomolar vs. micromolar) stems from the use of distinct analytical methods. The product page affinity was determined via the Octet RED System, a technique analogous to Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) that offers high sensitivity for kinetic and affinity measurements. In contrast, our study employed EMSA, a method primarily optimized for semi-quantitative assessment of binding interactions. The inherent differences in sensitivity and principle between these two techniques—with Octet RED System enabling real-time monitoring of biomolecular interactions and EMSA relying on gel separation—account for the observed variation in affinity values.

Second, regarding the competitive binding experiments, we appreciate your note on the critical role of reagent addition order and equilibration time. To eliminate potential biases from sequential addition, we clarify that Cy3-labeled RNAs, RBD proteins, and the neutralizing antibody were added simultaneously to the reaction system. We will revise the Methods section in the revised manuscript to provide a detailed protocol for the EMSA experiments, to ensure full reproducibility and appropriate interpretation of the results.

Third, we acknowledge and apologize for a critical error in the figure legends of Figure 3E: the concentrations reported (5 μM aptamer and antibody 40592-R001) refer to stock solutions, not the final concentrations in the EMSA reaction mixture. The correct final concentrations are 0.5 μM for aptamer Ta, and 0.5 μM for the antibody. This correction resolves the apparent inconsistency between Figure 3E and Figure 5D, as the final antibody concentration in Figure 3E is now consistent with the concentration range used in Figure 5D. We will update the figure legends for Figure 3E and revise the Methods section to explicitly distinguish between stock and final reaction concentrations, ensuring clarity and internal consistency of the results.

We sincerely thank you for highlighting these issues, which will prompt important revisions to improve the clarity, accuracy, and rigor of our manuscript.

(3) The utility of the approach for increasing affinity of RNA aptamers for their targets is well supported through computational and experimental techniques demonstrating relative improvements in binding affinity for their G34C variant compared to the starting Ta aptamer. While the EMSA experiments do have significant flaws, the observations of relative relationships in equilibrium binding affinities among the tested aptamer variants can be interpreted with reasonable confidence, given that they were all performed in a consistent manner.

We sincerely appreciate your valuable concerns and constructive feedback, which have greatly facilitated the improvement of our manuscript. Regarding the flaws of the EMSA experiments you pointed out, we have provided a detailed response to clarify the related issues and supplemented necessary experimental details to enhance the rigor and reproducibility of our work (see corresponding response above). It is worth noting that EMSA remains a classic and widely used technique for studying biomolecular interactions, and its reliability in qualitative and semi-quantitative analysis of binding events has been well recognized in the field. Furthermore, we fully agree with and are grateful for your view that, since all tested aptamer variants were analyzed using a consistent experimental protocol, the observations on the relative relationships of their equilibrium binding affinities can be interpreted with reasonable confidence. This recognition reinforces the validity of the relative affinity improvements we observed for the G34C variant compared to the parental Ta aptamer, which is a key finding of our study.

(4) The claim that the structure of the RBD-Aptamer complex predicted by the CAAMO pipeline is reliable is tenuous. The success of their rational design approach based on the structure predicted by several ensemble approaches supports the interpretation of the predicted structure as reasonable, however, no experimental validation is undertaken to assess the accuracy of the structure. This is not a main focus of the manuscript, given the applied nature of the study to identify Ta variants with improved binding affinity, however the structural accuracy claim is not strongly supported without experimental validation (i.e. chemical footprinting methods).

We thank the reviewer for this comment and agree that experimental validation would be required to establish the structural accuracy of the predicted RBD–aptamer complex. We note, however, that the primary aim of this study is not structural determination, but the development of a general computational framework for aptamer affinity maturation. In most practical applications, experimentally resolved structures of aptamer–protein complexes are unavailable. Accordingly, CAAMO is designed to operate under such conditions, using computationally generated binding models as working hypotheses to guide rational optimization rather than as definitive structural descriptions. In this context, the predicted structure is evaluated by its utility for affinity improvement, rather than by direct structural validation. We will revise the manuscript accordingly to further clarify this scope.

(5) Throughout the manuscript, the phrasing of "all tested antibodies" was used, despite there being only one tested antibody in experimental methods and three distinct antibodies in computational methods. While this concern is focused on specific language, the major conclusion that their designed aptamers are as good or better than neutralizing antibodies in general is weakened by only testing only three antibodies through computational binding measurements and a fourth single antibody for experimental testing. The contact residue mapping furthermore lacks clarity in the number of structures that were used, with a vague description of structures from the PDB including no accession numbers provided nor how many distinct antibodies were included for contact residue mapping.

We thank the reviewer for this important comment regarding language precision, experimental scope, and clarity of the antibody dataset used in this study. We agree that the phrase “all tested antibodies” was imprecise and could lead to overgeneralization. We will carefully revise the manuscript to use more accurate and explicit wording throughout, clearly distinguishing between experimentally tested antibodies, computationally analyzed antibodies, and antibody structures used for large-scale contact analysis.

Specifically, the experimental comparison in this study was performed using one commercially available SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody, whereas free energy–based computational analyses were conducted on three representative neutralizing antibodies with available structural data. We will revise the manuscript to explicitly state these distinctions and avoid general statements referring to neutralizing antibodies as a class.

Importantly, the residue-level contact frequency analysis was not based solely on these individual antibodies. Instead, this analysis leveraged a comprehensive set of experimentally resolved SARS-CoV-2 RBD–antibody complex structures curated from the Coronavirus Antibody Database (CoV-AbDab), a publicly available and actively maintained resource developed by the Oxford Protein Informatics Group. CoV-AbDab aggregates all published coronavirus-binding antibodies with associated PDB structures and provides a systematic and unbiased structural foundation for antibody–RBD interaction analysis. All available high-resolution RBD–antibody complex structures indexed in CoV-AbDab at the time of analysis were included to compute contact residue frequencies across the structural ensemble. We will explicitly state this data source, clarify the number and nature of structures used, and add the appropriate citation (Raybould et al., Bioinformatics, 2021, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa739).

Finally, we will revise the conclusions to avoid claims that extend beyond the scope of the data. The comparison between aptamers and antibodies is now framed in terms of representative antibodies and consensus interaction patterns derived from a large structural ensemble, rather than as a general statement about all neutralizing antibodies. These revisions will improve the clarity, rigor, and reproducibility of the manuscript, while preserving the core conclusion that the CAAMO framework enables effective structure-guided affinity maturation of RNA aptamers.

Overall, the manuscript by Yang et al presents a valuable tool for rational design of improved RNA aptamer binding affinity toward target proteins, which the authors call CAAMO. Notably, the method is not intended for de novo design, but rather as a tool for improving aptamers that have been selected for binding affinity by other methods such as SELEX. While there are significant issues in the conclusions made from experiments in this manuscript, the relative relationships of observed affinities within this study provide solid evidence that the CAAMO framework provides a valuable tool for researchers seeking to use rational design approaches for RNA aptamer affinity maturation.

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

In this study, the authors attempt to devise general rules for aptamer design based on structure and sequence features. The main system they are testing is an aptamer targeting a viral sequence.

Strengths:

The method combines a series of well-established protocols, including docking, MD, and a lot of system-specific knowledge, to design several new versions of the Ta aptamer with improved binding affinity.

We thank the reviewer for this accurate summary and for recognizing the strength of our integrated computational–experimental workflow in improving aptamer affinity.

Weaknesses:

The approach requires a lot of existing knowledge and, importantly, an already known aptamer, which presumably was found with SELEX. In addition, although the aptamer may have a stronger binding affinity, it is not clear if any of it has any additional useful properties such as stability, etc.

Thanks for these critical comments.

(1) On the reliance on a known aptamer: We agree that our CAAMO framework is designed as a post-SELEX optimization platform rather than a tool for de novo discovery. Its primary utility lies in rationally enhancing the affinity of existing aptamers that may not yet be sequence-optimal, thereby complementing experimental technologies such as SELEX. The following has been added to “Introduction” of the revised manuscript. (Page 5, line 108 in the revised manuscript)

‘Rather than serving as a de novo aptamer discovery tool, CAAMO is designed as a post-SELEX optimization platform that rationally improves the binding capability of existing aptamers.’

(2) On stability and developability: We also appreciate the reviewer’s important reminder that affinity alone is not sufficient for therapeutic development. We acknowledge that the present study has focused mainly on affinity optimization, and properties such as nuclease resistance, structural stability, and overall developability were not evaluated. The following has been added to “Discussion and conclusion” of the revised manuscript. (Page 25, line 595 in the revised manuscript)

‘While the present study primarily focused on affinity optimization, we acknowledge that other key developability traits—such as nuclease resistance, structural and thermodynamic stability, and in vivo persistence—are equally critical for advancing aptamers toward therapeutic applications. These properties were not evaluated here but will be systematically addressed in future iterations of the CAAMO framework to enable comprehensive optimization of aptamer candidates.’

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

This manuscript proposes a workflow for discovering and optimizing RNA aptamers, with application in the optimization of a SARS-CoV-2 RBD. The authors took a previously identified RNA aptamer, computationally docked it into one specific RBD structure, and searched for variants with higher predicted affinity. The variants were subsequently tested for RBD binding using gel retardation assays and competition with antibodies, and one was found to be a stronger binder by about three-fold than the founding aptamer.

Overall, this would be an interesting study if it were performed with truly high-affinity aptamers, and specificity was shown for RBD or several RBD variants.

Strengths:

The computational workflow appears to mostly correctly find stronger binders, though not de novo binders.

We thank the reviewer for the clear summary and for acknowledging that our workflow effectively prioritizes stronger binders.

Weaknesses:

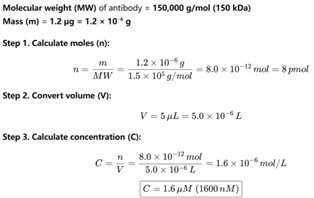

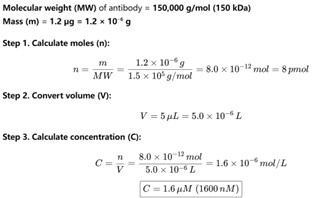

(1) Antibody competition assays are reported with RBD at 40 µM, aptamer at 5 µM, and a titration of antibody between 0 and 1.2 µg. This approach does not make sense. The antibody concentration should be reported in µM. An estimation of the concentration is 0-8 pmol (from 0-1.2 µg), but that's not a concentration, so it is unknown whether enough antibody molecules were present to saturate all RBD molecules, let alone whether they could have displaced all aptamers.

Thanks for your insightful comment. We have calculated that 0–1.2 µg antibody corresponds to a final concentration range of 0–1.6 µM (see Author response image 1). In practice, 1.2 µg was the maximum amount of commercial antibody that could be added under the conditions of our assay. In the revised manuscript, all antibody amounts previously reported in µg have been converted to their corresponding molar concentrations in Fig. 1F and Fig. 5D. In addition, the exact antibody concentrations used in the EMSA assays are now explicitly stated in the Materials and Methods section under “EMSA experiments.” The following has been added to “EMSA experiments” of the revised manuscript. (Page 30 in the revised manuscript)

‘For competitive binding experiments, 40 μM of RBP proteins, 5 μM of annealed Cy3-labelled RNAs and increasing concentrations of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody 40592-R001 (0–1.67 μM) were mixed in the EMSA buffer and incubated at room temperature for 20 min.’

Author response image 1.

Estimation of antibody concentration. Assuming a molecular weight of 150 kDa, dissolving 1.2 µg of antibody in a 5 µL reaction volume results in a final concentration of 1.6 µM.

As shown in Figure 5D, the purpose of the antibody–aptamer competition assay was not to achieve full saturation but rather to compare the relative competitive binding of the optimized aptamer (TaG34C) versus the parental aptamer (Ta). Molecular interactions at this scale represent a dynamic equilibrium of binding and dissociation. While the antibody concentration may not have been sufficient to saturate all available RBD molecules, the experimental results clearly reveal the competitive binding behavior that distinguishes the two aptamers. Specifically, two consistent trends emerged:

(1) Across all antibody concentrations, the free RNA band for Ta was stronger than that of TaG34C, while the RBD–RNA complex band of the latter was significantly stronger, indicating that TaG34C bound more strongly to RBD.

(2) For Ta, increasing antibody concentration progressively reduced the RBD–RNA complex band, consistent with antibody displacing the aptamer. In contrast, for TaG34C, the RBD–RNA complex band remained largely unchanged across all tested antibody concentrations, suggesting that the antibody was insufficient to displace TaG34C from the complex.

Together, these observations support the conclusion that TaG34C exhibits markedly stronger binding to RBD than the parental Ta aptamer, in line with the predictions and objectives of our CAAMO optimization framework.

(2) These are not by any means high-affinity aptamers. The starting sequence has an estimated (not measured, since the titration is incomplete) Kd of 110 µM. That's really the same as non-specific binding for an interaction between an RNA and a protein. This makes the title of the manuscript misleading. No high-affinity aptamer is presented in this study. If the docking truly presented a bound conformation of an aptamer to a protein, a sub-micromolar Kd would be expected, based on the number of interactions that they make.

In fact, our starting sequence (Ta) is a high-affinity aptamer, and then the optimized sequences (such as TaG34C) with enhanced affinity are undoubtedly also high-affinity aptamers. See descriptions below:

(1) Origin and prior characterization of Ta. The starting aptamer Ta (referred to as RBD-PB6-Ta in the original publication by Valero et al., PNAS 2021, doi:10.1073/pnas.2112942118) was selected through multiple positive rounds of SELEX against SARS-CoV-2 RBD, together with counter-selection steps to eliminate non-specific binders. In that study, Ta was reported to bind RBD with an IC₅₀ of ~200 nM as measured by biolayer interferometry (BLI), supporting its high affinity and specificity. The following has been added to “Introduction” of the revised manuscript. (Page 4 in the revised manuscript)

‘This aptamer was originally identified through SELEX and subsequently validated using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and biolayer interferometry (BLI), which confirmed its high affinity (sub-nanomolar) and high specificity toward the RBD. Therefore, Ta provides a well-characterized and biologically relevant starting point for structure-based optimization.’

(2) Methodological differences between EMSA and BLI measurements. We acknowledge that the discrepancy between our obtained binding affinity (Kd = 110 µM) and the previously reported one (IC50 ~ 200 nM) for the same Ta sequence arises primarily from methodological and experimental differences between EMSA and BLI. Namely, different experimental measurement methods can yield varied binding affinity values. While EMSA may have relatively low measurement precision, its relatively simple procedures were the primary reason for its selection in this study. Particularly, our framework (CAAMO) is designed not as a tool for absolute affinity determination, but as a post-SELEX optimization platform that prioritizes relative changes in binding affinity under a consistent experimental setup. Thus, the central aim of our work is to demonstrate that CAAMO can reliably identify variants, such as TaG34C, that bind more strongly than the parental sequence under identical assay conditions. The following has been added to “Discussion and conclusion” of the revised manuscript. (Page 24 in the revised manuscript)

‘Although the absolute Kd values determined by EMSA cannot be directly compared with surface-based methods such as SPR or BLI, the relative affinity trends remain highly consistent. While EMSA provides semi-quantitative affinity estimates, the close agreement between experimental EMSA trends and FEP-calculated ΔΔG values supports the robustness of the relative affinity changes reported here. In future studies, additional orthogonal biophysical techniques (e.g., filter-binding, SPR, or BLI) will be employed to further validate and refine the protein–aptamer interaction models.’

(3) Evidence of specific binding in our assays. We emphasize that the binding observed in our EMSA experiments reflects genuine aptamer–protein interactions. As shown in Figure 2G, a control RNA (Tc) exhibited no detectable binding to RBD, whereas Ta produced a clear binding curve, confirming that the interaction is specific rather than non-specific.

(3) The binding energies estimated from calculations and those obtained from the gel-shift experiments are vastly different, as calculated from the Kd measurements, making them useless for comparison, except for estimating relative affinities.

Author Reply: We thank the reviewer for raising this important point. CAAMO was developed as a post-SELEX optimization tool with the explicit goal of predicting relative affinity changes (ΔΔG) rather than absolute binding free energies (ΔG). Empirically, CAAMO correctly predicted the direction of affinity change for 5 out of 6 designed variants (e.g., ΔΔG < 0 indicates enhanced binding free energy relative to WT); such predictive power for relative ranking is highly valuable for prioritizing candidates for experimental testing. Our prior work on RNA–protein interactions likewise supports the reliability of relative affinity predictions (see: Nat Commun 2023, doi:10.1038/s41467-023-39410-8). The following has been added to “Discussion and conclusion” of the revised manuscript. (Page 24 in the revised manuscript)

‘While EMSA provides semi-quantitative affinity estimates, the close agreement between experimental EMSA trends and FEP-calculated ΔΔG values supports the robustness of the relative affinity changes reported here.’

Recommendations for the Authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for the authors)

(1) Overall, the paper is well-written and, in the opinion of this reviewer, could remain as it is.

We thank the reviewer for the positive evaluation and supportive comments regarding our manuscript. We are grateful for the endorsement of its quality and suitability for publication.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors)

(1) All molecules present in experiments need to be reported with their final concentrations (not µg).

We thank the reviewer for raising this important point. In the revised manuscript, all antibody amounts previously reported in µg have been converted to their corresponding molar concentrations in Fig. 1F and Fig. 5D. In addition, the exact antibody concentrations used in the EMSA assays are now explicitly stated in the Materials and Methods section under “EMSA experiments.” The following has been added to “EMSA experiments” of the revised manuscript. (Page 30 in the revised manuscript)

‘For competitive binding experiments, 40 μM of RBP proteins, 5 μM of annealed Cy3-labelled RNAs and increasing concentrations of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody 40592-R001 (0–1.67 μM) were mixed in the EMSA buffer and incubated at room temperature for 20 min.’

(2) An independent Kd measurement, for example, using a filter binding assay, would greatly strengthen the results.

We thank the reviewer for this constructive suggestion and agree that an orthogonal biophysical measurement (e.g., a filter-binding assay, SPR or BLI) would further strengthen confidence in the reported dissociation constants. Unfortunately, all available SARS-CoV-2 RBD protein used in this study has been fully consumed and, due to current supply limitations, we were unable to perform new orthogonal binding experiments for the revised manuscript. We regret this limitation and have documented it in the Discussion as an item for future work.

Importantly, although we could not perform a new filter-binding experiment at this stage, we have multiple independent lines of evidence that support the reliability of the EMSA-derived affinity trends reported in the manuscript:

(1) Rigorous EMSA design and reproducibility. All EMSA binding curves reported in the manuscript (e.g., Figs. 2F–G, 4E–F, 5A and Fig. S9) are derived from three independent biological replicates and include standard deviations; the measured binding curves show good reproducibility across replicates.

(2) Appropriate positive and negative controls. Our gel assays include clear internal controls. The literature-reported strong binder Ta forms a distinct aptamer–RBD complex band under our conditions, whereas the negative-control aptamer Tc shows no detectable binding under identical conditions (see Fig. 2F). These controls demonstrate that the EMSA system discriminates specific from non-binding sequences with high sensitivity.

(3) Orthogonal computational validation (FEP) that agrees with experiment. The central strength of the CAAMO framework is the integration of rigorous physics-based calculations with experiments. We performed FEP calculations for the selected single-nucleotide mutations and computed ΔΔG values for each mutant. The direction and rank order of binding changes predicted by FEP are in good agreement with the EMSA measurements: five of six FEP-predicted improved mutants (TaG34C, TaG34U, TaG34A, TaC23A, TaC23U) were experimentally confirmed to have stronger apparent affinity than wild-type Ta (see Fig. 4D–F, Table S2), yielding a success rate of 83%. The concordance between an independent, rigorous computational method and our experimental measurements provides strong mutual validation.

(4) Independent competitive binding experiments. We additionally performed competitive EMSA assays against a commercial neutralizing monoclonal antibody (40592-R001). These competition experiments show that TaG34C–RBD complexes are resistant to antibody displacement under conditions that partially displace the wild-type Ta–RBD complex (see Fig. 5D). This result provides an independent, functionally relevant line of evidence that TaG34C binds RBD with substantially higher affinity and specificity than WT Ta under our assay conditions.

Given these multiple, independent lines of validation (rigorous EMSA replicates and controls, FEP agreement, and antibody competition assays), we are confident that the relative affinity improvements reported in the manuscript are robust, even though the absolute Kd values measured by EMSA are not directly comparable to surface-based methods (EMSA typically reports larger apparent Kd values than SPR/BLI due to methodological differences). The following has been added to “Discussion and conclusion” of the revised manuscript. (Page 24 in the revised manuscript)

‘Although the absolute Kd values determined by EMSA cannot be directly compared with surface-based methods such as SPR or BLI, the relative affinity trends remain highly consistent. While EMSA provides semi-quantitative affinity estimates, the close agreement between experimental EMSA trends and FEP-calculated ΔΔG values supports the robustness of the relative affinity changes reported here. In future studies, additional orthogonal biophysical techniques (e.g., filter-binding, SPR, or BLI) will be employed to further validate and refine the protein–aptamer interaction models.’

(3) The project would really benefit from a different aptamer-target system. Starting with a 100 µM aptamer is really not adequate.

We thank the reviewer for this important suggestion and for highlighting the value of testing the CAAMO framework in additional aptamer–target systems.

First, we wish to clarify the rationale for selecting the Ta–RBD system as the proof-of-concept. The Ta aptamer is not an arbitrary or weak binder: it was originally identified by independent SELEX experiments and subsequently validated by rigorous biophysical assays (SPR and BLI) (see: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2021, doi: 10.1073/pnas.2112942118). That study confirmed that Ta exhibits high-affinity and high-specificity binding to the SARS-CoV-2 RBD, which is why it serves as a well-characterized and biologically relevant system for method validation and optimization. We have added a brief clarification to the “Introduction” to emphasize these points. The following has been added to “Introduction” of the revised manuscript. (Page 4 in the revised manuscript)

‘This aptamer was originally identified through SELEX and subsequently validated using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and biolayer interferometry (BLI), which confirmed its high affinity and high specificity toward the RBD. Therefore, Ta provides a well-characterized and biologically relevant starting point for structure-based optimization.’

Second, we agree that apparent discrepancies in absolute Kd values can arise from different experimental platforms. Surface-based methods (SPR/BLI) and gel-shift assays (EMSA) have distinct measurement principles; EMSA yields semi-quantitative, solution-phase, apparent Kd values that are not directly comparable in absolute magnitude to surface-based measurements. Crucially, however, our study focuses on relative affinity change. EMSA is well suited for parallel, comparative measurements across multiple variants when all samples are assayed under identical conditions, and thus provides a reliable readout for ranking and validating designed mutations. We have added a short statement in the “Discussion and conclusion”. The following has been added to “Discussion and conclusion” of the revised manuscript. (Page 24 in the revised manuscript)

‘Although the absolute Kd values determined by EMSA cannot be directly compared with surface-based methods such as SPR or BLI, the relative affinity trends remain highly consistent. While EMSA provides semi-quantitative affinity estimates, the close agreement between experimental EMSA trends and FEP-calculated ΔΔG values supports the robustness of the relative affinity changes reported here. In future studies, additional orthogonal biophysical techniques (e.g., filter-binding, SPR, or BLI) will be employed to further validate and refine the protein–aptamer interaction models.’

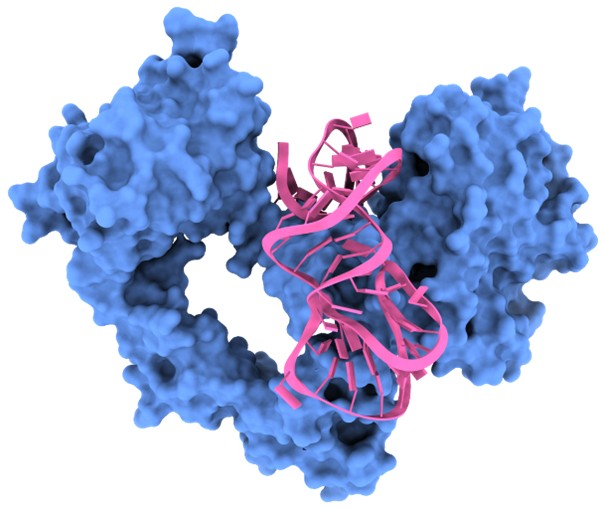

Third, and importantly, CAAMO is inherently generalizable. In addition to the Ta–RBD application presented here, we have already begun applying CAAMO to other aptamer–target systems. In particular, we have successfully deployed the framework in preliminary optimization studies of RNA aptamers targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (see: Gastroenterology 2021, doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2021.05.055) (see Author response image 2). These preliminary results support the transferability of the CAAMO pipeline beyond the SARS-CoV-2 RBD system. We have added a short statement in the “Discussion and conclusion”. The following has been added to “Discussion and conclusion” of the revised manuscript. (Page 259 in the revised manuscript)

‘In addition to the Ta–RBD system, the CAAMO framework itself is inherently generalizable. More work is currently underway to apply CAAMO to optimize aptamers targeting other therapeutically relevant proteins, such as the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [45], in order to further explore its potential for broader aptamer engineering.’

Author response image 2.

Overview of the predicted binding model of the EGFR–aptamer complex generated using the CAAMO framework.

(4) Several RBD variants should be tested, as well as other proteins, for specificity. At such weak affinities, it is likely that these are non-specific binders.

We thank the reviewer for this important concern. Below we clarify the basis for selecting Ta and its engineered variants, summarize the experimental controls that address specificity, and present the extensive in silico variant analysis we performed to assess sensitivity and breadth of binding.

(1) Origin and validation of Ta. As noted in our response to “Comment (3)”, the Ta aptamer was not chosen arbitrarily. Ta was identified by independent SELEX with both positive and negative selection and subsequently validated using surface-based biophysical assays (SPR and BLI), which reported low-nanomolar affinity and high specificity for the SARS-CoV-2 RBD. Thus, Ta is a well-characterized, experimentally validated starting lead for method development and optimization.

(2) Experimental specificity controls. We appreciate the concern that weak apparent affinities can reflect non-specific binding. As noted in our response to “Comment (2)”, we applied multiple experimental controls that argue against non-specificity: (i) a literature-reported weak binder (Tc) was used as a negative control and produced no detectable complex under identical EMSA conditions (see Figs. 2F–G), demonstrating the assay’s ability to discriminate non-binders from specific binders; (ii) competitive EMSA assays with a commercial neutralizing monoclonal antibody (40592-R001) show that both Ta and TaG34C engage the same or overlapping RBD site as the antibody, and that TaG34C is substantially more resistant to antibody displacement than WT Ta (see Figs. 3D–E, 5D). Together, these wet-lab controls support that the observed aptamer-RBD bands reflect specific interactions rather than general, non-specific adsorption.

(3) Variant and specificity analysis by rigorous FEP calculations. To address the reviewer’s request to evaluate variant sensitivity, we performed extensive free energy perturbation combined with Hamiltonian replica-exchange molecular dynamics (FEP/HREX) for improved convergence efficiency and increased simulation time to estimate relative binding free energy changes (ΔΔG) of both WT Ta and the optimized TaG34C against a panel of RBD variants. Results are provided in Tables S4 and S5. Representative findings include: For WT Ta versus early lineages, FEP reproduces the experimentally observed trends: Alpha (B.1.1.7; N501Y) yields ΔΔGFEP = −0.42 ± 0.07 kcal/mol (ΔΔGexp = −0.24), while Beta (B.1.351; K417N/E484K/N501Y) gives ΔΔGFEP = 0.64 ± 0.25 kcal/mol (ΔΔGexp = 0.36) (see Table S4). The agreement between the computational and experimental results supports the fidelity of our computational model for variant assessment. For the engineered TaG34C, calculations across a broad panel of variants indicate that TaG34C retains or improves binding (ΔΔG < 0) for the majority of tested variants, including Alpha, Beta, Gamma and many Omicron sublineages. Notable examples: BA.1 (ΔΔG = −3.00 ± 0.52 kcal/mol), BA.2 (ΔΔG = −2.54 ± 0.60 kcal/mol), BA.2.75 (ΔΔG = −5.03 ± 0.81 kcal/mol), XBB (ΔΔG = −3.13 ± 0.73 kcal/mol) and XBB.1.5 (ΔΔG = −2.28 ± 0.96 kcal/mol). A minority of other Omicron sublineages (e.g., BA.4 and BA.5) show modest positive ΔΔG values (2.11 ± 0.67 and 2.27 ± 0.68 kcal/mol, respectively), indicating a predicted reduction in affinity for those specific backgrounds. Overall, these data indicate that the designed TaG34C aptamer can maintain its binding ability with most SARS-CoV-2 variants, showing potential for broad-spectrum antiviral activity (see Table S5). The following has been added to “Results” of the revised manuscript. (Page 22 in the revised manuscript)

‘2.6 Binding performance of Ta and TaG34C against SARS-CoV-2 RBD variants

To further evaluate the binding performance and specificity of the designed aptamer TaG34C toward various SARS-CoV-2 variants [39], we conducted extensive free energy perturbation combined with Hamiltonian replica-exchange molecular dynamics (FEP/HREX) [40–42] for both the wild-type aptamer Ta and the optimized TaG34C against a series of RBD mutants. The representative variants include the early Alpha (B.1.1.7) and Beta (B.1.351) lineages, as well as a panel of Omicron sublineages (BA.1–BA.5, BA.2.75, BQ.1, XBB, XBB.1.5, EG.5.1, HK.3, JN.1, and KP.3) carrying multiple mutations within the RBD region (residues 333–527). For each variant, mutations within 5 Å of the bound aptamer were included in the FEP to accurately estimate the relative binding free energy change (ΔΔG).

For the wild-type Ta aptamer, the FEP-predicted binding affinities toward the Alpha and Beta RBD variants were consistent with the previous experimental results, further validating the reliability of our model (see Table S4). Specifically, Ta maintained comparable or slightly enhanced binding to the Alpha variant and showed only marginally reduced affinity for the Beta variant.

In contrast, the optimized aptamer TaG34C exhibited markedly improved and broad-spectrum binding capability toward most tested variants (see Table S5). For early variants such as Alpha, Beta, and Gamma, TaG34C maintained enhanced affinities (ΔΔG < 0). Notably, for multiple Omicron sublineages—including BA.1, BA.2, BA.2.12.1, BA.2.75, XBB, XBB.1.5, XBB.1.16, XBB.1.9, XBB.2.3, EG.5.1, XBB.1.5.70, HK.3, BA.2.86, JN.1 and JN.1.11.1—the calculated binding free energy changes ranged from −1.89 to −7.58 kcal/mol relative to the wild-type RBD, indicating substantially stronger interactions despite the accumulation of multiple mutations at the aptamer–RBD interface. Only in a few other Omicron sublineages, such as BA.4, BA.5, and KP.3, a slight reduction in binding affinity was observed (ΔΔG > 0).

These computational findings demonstrate that the TaG34C aptamer not only preserves high affinity for the RBD but also exhibits improved tolerance to the extensive mutational landscape of SARS-CoV-2. Collectively, our results suggest that TaG34C holds promise as a high-affinity and potentially cross-variant aptamer candidate for targeting diverse SARS-CoV-2 spike protein variants, showing potential for broad-spectrum antiviral activity.’

The following has been added to “Materials and Methods” of the revised manuscript. (Page 29 in the revised manuscript)

‘4.7 FEP/HREX

To evaluate the binding sensitivity of the optimized aptamer TaG34C toward SARS-CoV-2 RBD variants, we employed free energy perturbation combined with Hamiltonian replica-exchange molecular dynamics (FEP/HREX) simulations for enhanced sampling efficiency and improved convergence. The relative binding free energy changes (ΔΔG) upon RBD mutations were estimated as:

ΔΔ𝐺 = Δ𝐺bound − Δ𝐺free

where ΔGbound and ΔGfree represent the RBD mutations-induced free energy changes in the complexed and unbound states, respectively. All simulations were performed using GROMACS 2021.5 with the Amber ff14SB force field. For each mutation, dual-topology structures were generated in a pmx-like manner, and 32 λ-windows (0.0, 0.01, 0.02, 0.03, 0.06, 0.09, 0.12, 0.16, 0.20, 0.24, 0.28, 0.32, 0.36, 0.40, 0.44, 0.48, 0.52, 0.56, 0.60, 0.64, 0.68, 0.72, 0.76, 0.80, 0.84, 0.88, 0.91, 0.94, 0.97, 0.98, 0.99, 1.0) were distributed uniformly between 0.0 and 1.0. To ensure sufficient sampling, each window was simulated for 5 ns, with five independent replicas initiated from distinct velocity seeds. Replica exchange between adjacent λ states was attempted every 1 ps to enhance phase-space overlap and sampling convergence. The van der Waals and electrostatic transformations were performed simultaneously, employing a soft-core potential (α = 0.3) to avoid singularities. For each RBD variant system, this setup resulted in an accumulated simulation time of approximately 1600 ns (5 ns × 32 windows × 5 replicas × 2 states). The Gromacs bar analysis tool was used to estimate the binding free energy changes.’

Tables S4 and S5 have been added to Supplementary Information of the revised manuscript.

-

-

-

-

eLife Assessment

This study presents a computational-experimental workflow for optimizing RNA aptamers targeting SARS-CoV-2 RBD. While the integrated approach combining docking, molecular dynamics, and experimental validation shows some promise, the useful findings are limited by the extremely weak binding affinities (>100 µM KD) and restriction to a single target system. The evidence is incomplete, with experimental design issues in the antibody competition assays and a lack of specificity testing undermining confidence in the conclusions.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

In this study, the authors attempt to devise general rules for aptamer design based on structure and sequence features. The main system they are testing is an aptamer targeting a viral sequence.

Strengths:

The method combines a series of well-established protocols, including docking, MD, and a lot of system-specific knowledge, to design several new versions of the Ta aptamer with improved binding affinity.

Weaknesses:

The approach requires a lot of existing knowledge and, importantly, an already known aptamer, which presumably was found with Selex. In addition, although the aptamer may have a stronger binding affinity, it is not clear if any of it has any additional useful properties such as stability, etc.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

This manuscript proposes a workflow for discovering and optimizing RNA aptamers, with application in the optimization of a SARS-CoV-2 RBD. The authors took a previously identified RNA aptamer, computationally docked it into one specific RBD structure, and searched for variants with higher predicted affinity. The variants were subsequently tested for RBD binding using gel retardation assays and competition with antibodies, and one was found to be a stronger binder by about three-fold than the founding aptamer.

Overall, this would be an interesting study if it were performed with truly high-affinity aptamers, and specificity was shown for RBD or several RBD variants.

Strengths:

The computational workflow appears to mostly correctly find stronger binders, though not de novo binders.

Weaknesses:

(1) …

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

This manuscript proposes a workflow for discovering and optimizing RNA aptamers, with application in the optimization of a SARS-CoV-2 RBD. The authors took a previously identified RNA aptamer, computationally docked it into one specific RBD structure, and searched for variants with higher predicted affinity. The variants were subsequently tested for RBD binding using gel retardation assays and competition with antibodies, and one was found to be a stronger binder by about three-fold than the founding aptamer.

Overall, this would be an interesting study if it were performed with truly high-affinity aptamers, and specificity was shown for RBD or several RBD variants.

Strengths:

The computational workflow appears to mostly correctly find stronger binders, though not de novo binders.

Weaknesses:

(1) Antibody competition assays are reported with RBD at 40 µM, aptamer at 5 µM, and a titration of antibody between 0 and 1.2 µg. This approach does not make sense. The antibody concentration should be reported in µM. An estimation of the concentration is 0-8 pmol (from 0-1.2 µg), but that's not a concentration, so it is unknown whether enough antibody molecules were present to saturate all RBD molecules, let alone whether they could have displaced all aptamers.

(2) These are not by any means high-affinity aptamers. The starting sequence has an estimated (not measured, since the titration is incomplete) KD of 110 µM. That's really the same as non-specific binding for an interaction between an RNA and a protein. This makes the title of the manuscript misleading. No high-affinity aptamer is presented in this study. If the docking truly presented a bound conformation of an aptamer to a protein, a sub-micromolar Kd would be expected, based on the number of interactions that they make.

(3) The binding energies estimated from calculations and those obtained from the gel-shift experiments are vastly different, as calculated from the Kd measurements, making them useless for comparison, except for estimating relative affinities.

-

Author response:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

In this study, the authors attempt to devise general rules for aptamer design based on structure and sequence features. The main system they are testing is an aptamer targeting a viral sequence.

Strengths:

The method combines a series of well-established protocols, including docking, MD, and a lot of system-specific knowledge, to design several new versions of the Ta aptamer with improved binding affinity.

We thank the reviewer for this accurate summary and for recognizing the strength of our integrated computational–experimental workflow in improving aptamer affinity. We will emphasize this contribution more clearly in the revised Introduction.

Weaknesses:

The approach requires a lot of existing knowledge and, impo rtantly, an already known aptamer, which presumably was found …

Author response:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

In this study, the authors attempt to devise general rules for aptamer design based on structure and sequence features. The main system they are testing is an aptamer targeting a viral sequence.

Strengths:

The method combines a series of well-established protocols, including docking, MD, and a lot of system-specific knowledge, to design several new versions of the Ta aptamer with improved binding affinity.

We thank the reviewer for this accurate summary and for recognizing the strength of our integrated computational–experimental workflow in improving aptamer affinity. We will emphasize this contribution more clearly in the revised Introduction.

Weaknesses:

The approach requires a lot of existing knowledge and, impo rtantly, an already known aptamer, which presumably was found with SELEX. In addition, although the aptamer may have a stronger binding affinity, it is not clear if any of it has any additional useful properties such as stability, etc.

Thanks for these critical comments.

(1) On the reliance on a known aptamer: We agree that our CAAMO framework is designed as a post-SELEX optimization platform rather than a tool for de novo discovery. Its primary utility lies in rationally enhancing the affinity of existing aptamers that may not yet be sequence-optimal, thereby complementing experimental technologies such as SELEX. In the revised manuscript, we plan to clarify this point more explicitly in both the Introduction and Discussion sections, emphasizing that the propose CAAMO framework is intended to serve as a complementary strategy that accelerates the iterative optimization of lead aptamers.

(2) On stability and developability: We also appreciate the reviewer’s important reminder that affinity alone is not sufficient for therapeutic development. We acknowledge that the present study has focused mainly on affinity optimization, and properties such as nuclease resistance, structural stability, and overall developability were not evaluated. In the revised manuscript, we will add a dedicated section highlighting the critical importance of these characteristics and outlining them as key priorities for our future research efforts.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

This manuscript proposes a workflow for discovering and optimizing RNA aptamers, with application in the optimization of a SARS-CoV-2 RBD. The authors took a previously identified RNA aptamer, computationally docked it into one specific RBD structure, and searched for variants with higher predicted affinity. The variants were subsequently tested for RBD binding using gel retardation assays and competition with antibodies, and one was found to be a stronger binder by about three-fold than the founding aptamer. Overall, this would be an interesting study if it were performed with truly high-affinity aptamers, and specificity was shown for RBD or several RBD variants.

Strengths:

The computational workflow appears to mostly correctly find stronger binders, though not de novo binders.

We thank the reviewer for the clear summary and for acknowledging that our workflow effectively prioritizes stronger binders.

Weaknesses:

(1) Antibody competition assays are reported with RBD at 40 µM, aptamer at 5 µM, and a titration of antibody between 0 and 1.2 µg. This approach does not make sense. The antibody concentration should be reported in µM. An estimation of the concentration is 0-8 pmol (from 0-1.2 µg), but that's not a concentration, so it is unknown whether enough antibody molecules were present to saturate all RBD molecules, let alone whether they could have displaced all aptamers.

Thanks for your insightful comment. We have calculated that 0–1.2 µg antibody corresponds to a final concentration range of 0–1.6 µM (see Author response image 1). In practice, 1.2 µg was the maximum amount of commercial antibody that could be added under the conditions of our assay. In the revised manuscript, we plan to report all antibody quantities in molar concentrations in the Materials and Methods section for clarity and rigor.

Author response image 1.

Estimation of antibody concentration. Assuming a molecular weight of 150 kDa, dissolving 1.2 µg of antibody in a 5 µL reaction volume results in a final concentration of 1.6 µM.

As shown in Figure 5D of the main text, the purpose of the antibody–aptamer competition assay was not to achieve full saturation but rather to compare the relative competitive binding of the optimized aptamer (TaG34C) versus the parental aptamer (Ta). Molecular interactions at this scale represent a dynamic equilibrium of binding and dissociation. While the antibody concentration may not have been sufficient to saturate all available RBD molecules, the experimental results clearly reveal the competitive binding behavior that distinguishes the two aptamers. Specifically, two consistent trends emerged:

(1) Across all antibody concentrations, the free RNA band for Ta was stronger than that of TaG34C, while the RBD–RNA complex band of the latter was significantly stronger, indicating that TaG34Cbound more strongly to RBD.

(2) For Ta, increasing antibody concentration progressively reduced the RBD–RNA complex band, consistent with antibody displacing the aptamer. In contrast, for TaG34C, the RBD–RNA complex band remained largely unchanged across all tested antibody concentrations, suggesting that the antibody was insufficient to displace TaG34C from the complex.

Together, these observations support the conclusion that TaG34C exhibits markedly stronger binding to RBD than the parental Ta aptamer, in line with the predictions and objectives of our CAAMO optimization framework.

(2) These are not by any means high-affinity aptamers. The starting sequence has an estimated (not measured, since the titration is incomplete) KD of 110 µM. That's really the same as non-specific binding for an interaction between an RNA and a protein. This makes the title of the manuscript misleading. No high-affinity aptamer is presented in this study. If the docking truly presented a bound conformation of an aptamer to a protein, a sub-micromolar Kd would be expected, based on the number of interactions that they make.

In fact, our starting sequence (Ta) is a high-affinity aptamer, and then the optimized sequences (such as TaG34C) with enhanced affinity are undoubtedly also high-affinity aptamers. See descriptions below:

(1) Origin and prior characterization of Ta. The starting aptamer Ta (referred to as RBD-PB6-Ta in the original publication by Valero et al., PNAS 2021, doi:10.1073/pnas.2112942118) was selected through multiple positive rounds of SELEX against SARS-CoV-2 RBD, together with counter-selection steps to eliminate non-specific binders. In that study, Ta was reported to bind RBD with an IC₅₀ of ~200 nM as measured by biolayer interferometry (BLI), supporting its high affinity and specificity.

(2) Methodological differences between EMSA and BLI measurements. We acknowledge that the discrepancy between our obtained binding affinity (Kd = 110 µM) and the previously reported one (IC₅₀ ~ 200 nM) for the same Ta sequence arises primarily from methodological and experimental differences between EMSA and BLI. Namely, different experimental measurement methods can yield varied binding affinity values. While EMSA may have relatively low measurement precision, its relatively simple procedures were the primary reason for its selection in this study. Particularly, our framework (CAAMO) is designed not as a tool for absolute affinity determination, but as a post-SELEX optimization platform that prioritizes relative changes in binding affinity under a consistent experimental setup. Thus, the central aim of our work is to demonstrate that CAAMO can reliably identify variants, such as TaG34C, that bind more strongly than the parental sequence under identical assay conditions.

(3) Evidence of specific binding in our assays. We emphasize that the binding observed in our EMSA experiments reflects genuine aptamer–protein interactions. As shown in Figure 2G of the main text, a control RNA (Tc) exhibited no detectable binding to RBD, whereas Ta produced a clear binding curve, confirming that the interaction is specific rather than non-specific.

(3) The binding energies estimated from calculations and those obtained from the gel-shift experiments are vastly different, as calculated from the Kd measurements, making them useless for comparison, except for estimating relative affinities.

We thank the reviewer for raising this important point. CAAMO was developed as a post-SELEX optimization tool with the explicit goal of predicting relative affinity changes (ΔΔG) rather than absolute binding free energies (ΔG). Empirically, CAAMO correctly predicted the direction of affinity change for 5 out of 6 designed variants (e.g., ΔΔG < 0 indicates enhanced binding free energy relative to WT); such predictive power for relative ranking is highly valuable for prioritizing candidates for experimental testing. Our prior work on RNA–protein interactions likewise supports the reliability of relative affinity predictions (see: Nat Commun 2023, doi:10.1038/s41467-023-39410-8). In the revised manuscript we will explicitly state that the primary utility of CAAMO is to accurately predict affinity trends and to rank variants for follow-up, and we will moderate any statements that could be interpreted as claims about precise absolute ΔΔG values.

-