CCDC32 stabilizes clathrin-coated pits and drives their invagination

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

eLife Assessment

The manuscript presents a valuable finding that CCDC32, beyond its reported role in AP2 assembly, follows AP2 to the plasma membrane and regulates clathrin-coated pit assembly and dynamics. The authors further identify an alpha-helical region within CCDC32 that is essential for its interaction with AP2 and its cellular function. While live-cell and ultrastructural imaging data are solid, future biochemical studies will be needed to confirm the proposed CCDC32-AP2 interaction.

[Editors' note: this paper was reviewed by Review Commons.]

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

- Evaluated articles (Review Commons)

Abstract

Clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) is essential for maintaining homeostasis in mammalian cells. Previous studies have reported more than 50 CME accessory proteins; however, the mechanism driving the invagination of clathrin-coated pits (CCPs) remains elusive. We show by quantitative live cell imaging that siRNA-mediated knockdown of CCDC32, a poorly characterized endocytic accessory protein, leads to the accumulation of unstable flat clathrin assemblies. CCDC32 interacts with the α-appendage domain (AD) of AP2 in vitro and with full-length AP2 complexes in cells. Deletion of aa78-98 in CCDC32, corresponding to a predicted α-helix, abrogates AP2 binding and CCDC32’s early function in CME. Furthermore, clinically observed nonsense mutations in CCDC32, which result in C-terminal truncations that lack aa78-98, are linked to the development of cardio-facio-neuro-developmental syndrome (CFNDS). Overall, our data demonstrate the function of a novel endocytic accessory protein, CCDC32, in regulating CCP stabilization and invagination, critical early stages of CME.

Article activity feed

-

-

-

-

eLife Assessment

The manuscript presents a valuable finding that CCDC32, beyond its reported role in AP2 assembly, follows AP2 to the plasma membrane and regulates clathrin-coated pit assembly and dynamics. The authors further identify an alpha-helical region within CCDC32 that is essential for its interaction with AP2 and its cellular function. While live-cell and ultrastructural imaging data are solid, future biochemical studies will be needed to confirm the proposed CCDC32-AP2 interaction.

[Editors' note: this paper was reviewed by Review Commons.]

-

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Yang et al. describes CCDC32 as a new clathrin mediated endocytosis (CME) accessory protein. The authors show that CCDC32 binds directly to AP2 via a small alpha helical region and cells depleted for this protein show defective CME. Finally, the authors show that the CCDC32 nonsense mutations found in patients with cardio-facial-neuro-developmental syndrome (CFNDS) disrupt the interaction of this protein to the AP2 complex. The results presented suggest that CCDC32 may act as both a chaperone (as recently published) and a structural component of the AP2 complex.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors responded to my previous concerns with additional arguments and discussion. While I do not object to the publication of this work, two critical experiments are still missing.Weaknesses:

First, biochemical assays using recombinant proteins should be conducted to determine whether CCDC32 binds to the full AP2 adaptor or to specific AP2 intermediates, such as hemicomplexes. The current co-IP data from mammalian cell lysates are too complex to interpret conclusively. Second, cell fractionation should be performed to assess whether, and how, CCDC32 associates with membrane-bound AP2. -

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

In this manuscript, Yang et al. characterize the endocytic accessory protein CCDC32, which has implications in cardio-facio-neuro-developmental syndrome (CFNDS). The authors clearly demonstrate that the protein CCDC32 has a role in the early stages of endocytosis, mainly through the interaction with the major endocytic adaptor protein AP2, and they identify regions taking part in this recognition. Through live cell fluorescence imaging and electron microscopy of endocytic pits, the authors characterize the lifetimes of endocytic sites, the formation rate of endocytic sites and pits and the invagination depth, in addition to transferrin receptor (TfnR) uptake experiments. Binding between CCDC32 and CCDC32 mutants to the AP2 alpha appendage domain is assessed by pull down experiments.

Together, these …

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

In this manuscript, Yang et al. characterize the endocytic accessory protein CCDC32, which has implications in cardio-facio-neuro-developmental syndrome (CFNDS). The authors clearly demonstrate that the protein CCDC32 has a role in the early stages of endocytosis, mainly through the interaction with the major endocytic adaptor protein AP2, and they identify regions taking part in this recognition. Through live cell fluorescence imaging and electron microscopy of endocytic pits, the authors characterize the lifetimes of endocytic sites, the formation rate of endocytic sites and pits and the invagination depth, in addition to transferrin receptor (TfnR) uptake experiments. Binding between CCDC32 and CCDC32 mutants to the AP2 alpha appendage domain is assessed by pull down experiments.

Together, these experiments allow deriving a phenotype of CCDC32 knock-down and CCDC32 mutants within endocytosis, which is a very robust system, in which defects are not so easily detected. A mutation of CCDC32, mimicking CFNDS mutations, is also addressed in this study and shown to have endocytic defects.

An experimental proof for the resistance of the different CCDC32 mutants to siRNA treatment would have helped to strengthen the conclusions.

In summary, the authors present a strong combination of techniques, assessing the impact of CCDC32 in clathrin mediated endocytosis and its binding to AP2.

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

This is a revision of a manuscript previously submitted to Review Commons. The authors have partially addressed my comments, mainly by expanding the introduction and discussion sections. Sandy Schmid, a leading expert on the AP2 adaptor and CME, has been added as a co-corresponding author. The main message of the manuscript remains unchanged. Through overexpression of fluorescently tagged CCDC32, the authors propose that, in addition to its established role in AP2 assembly, CCDC32 also follows AP2 to the plasma membrane and regulates CCP maturation. The manuscript presents some interesting ideas, but there are still concerns regarding data inconsistencies and gaps in the evidence.

With due respect, we would argue that a role …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

This is a revision of a manuscript previously submitted to Review Commons. The authors have partially addressed my comments, mainly by expanding the introduction and discussion sections. Sandy Schmid, a leading expert on the AP2 adaptor and CME, has been added as a co-corresponding author. The main message of the manuscript remains unchanged. Through overexpression of fluorescently tagged CCDC32, the authors propose that, in addition to its established role in AP2 assembly, CCDC32 also follows AP2 to the plasma membrane and regulates CCP maturation. The manuscript presents some interesting ideas, but there are still concerns regarding data inconsistencies and gaps in the evidence.

With due respect, we would argue that a role for CCDC32 in AP2 assembly is hardly ‘established’. Rather a single publication reporting its role as a co-chaperone for AAGAP appeared while our manuscript was under review. We find some similar and some conflicting results, which are described in our revised manuscript. However, in combination our two papers clearly show that CCDC32, a previously unrecognized endocytic accessory protein, deserves further study.

(1) eGFP-CCDC32 was expressed at 5-10 times higher levels than endogenous CCDC32. This high expression can artificially drive CCDC32 to the cell surface via binding to the alpha appendage domain (AD)-an interaction that may not occur under physiological conditions.

While we acknowledge that overexpression of eGFP-CCDC32 could result in artificially driving it to CCPs, we do not believe this is the case for the following reasons:

i. The bulk of our studies (Figures 2-4) demonstrate the effects of siRNA knockdown on CCDC32 on CCP early stages of CME, and so it is likely that these functions require the presence of endogenous CCDC32 at nascent CCPs as detected with overexpressed eGFP-CCDC32 by TIRF imaging.

ii. At these levels of overexpression eGFP-CCDC32 fully rescues the effects of siRNA KD of endogenous CCCDC32 of Tfn uptake and CCP dynamics (Figure 6F,G). If the protein was artificially recruited to the AP2 appendage domain, one would expect it to compete with the recruitment of other EAPS to CCPs and hence exhibit defects in CCP dynamics. Indeed, we see the opposite: CCPs that are positive for eGFP-CCDC32 show normal dynamics and maturation rates, while CCPs lacking eGFP-CCDC32 are short-lived and more likely to be aborted (Figure 1C).

iii. We have identified two modes of binding of CCDC32 to AP2 adaptors: one is through canonical AP2-AD binding motifs, the second is through an a-helix in CCDC32 that, by modeling, docks only to the open conformation of AP2. Overexpressed CCDC32 lacking this a-helix is not recruited to CCPs (Fig. 6 D,E), indicating that the canonical AP2 binding motifs are not sufficient to recruit CCDC32 to CCPs, even when overexpressed.

(2) Which region of CCDC32 mediates alpha AD binding? Strangely, the only mutant tested in this work, Δ78-98, still binds AP2, but shifts to binding only mu and beta. If the authors claim that CCDC32 is recruited to mature AP2 via the alpha AD, then a mutant deficient in alpha AD binding should not bind AP2 at all. Such a mutant is critical for establish the model proposed in this work.

We understand the reviewer’s confusion and thus devoted a paragraph in the discussion to this issue. As revealed by AlphaFold 3.0 modeling (Figure S6) binding of CCDC32 to the alpha AD likely occurs via the 2 canonical AP2-AD binding motifs encoded in CCDC32. Given the highly divergent nature of AP2-AD binding motifs, we did not identify these motifs without the AlphaFold 3.0 modeling. While these interactions could be detected by GST-pull downs, they are apparently not of sufficient affinity to recruit CCDC32 to CCPs in cells. In the text, we now describe the a-helix we identified as being essential of CCP recruitment as ‘a’ AP2 binding site on CCDC32 rather than ‘the’ AP2 binding site. Interestingly, and also discussed, Alphafold 3.0 identifies a highly predicted docking site on a-adaptin that is only accessible in the open, cargo-bound conformation of intact AP2. This is also consistent with the inability of CCDC32(D78-99) to bind the a:µ2 hemi-complex in cell lysates.

We agree that further structural studies on CCDC32’s interactions with AP2 and its targeting to CCPs will be of interest for future work.

(3) The concept of hemicomplexes is introduced abruptly. What is the evidence that such hemicomplexes exist? If CCDC32 binds to hemicomplexes, this must occur in the cytosol, as only mature AP2 tetramers are recruited to the plasma membrane. The authors state that CCDC32 binds the AD of alpha but not beta, so how can the Δ78-98 mutant bind mu and beta?

We introduced the concept of hemicomplexes based on our unexpected (and now explicitly stated as such) finding that the CCDC32(D78-99) mutant efficiently co-IPs with a b2:µ2 hemicomplex. As stated, the efficiency of this pulldown suggests that the presumed stable AP2 heterotetramer must indeed exist in equilibrium between the two a:s2 and b2:µ2 hemicomplexes, such that CCDC32(D78-99) can sequester and efficiently co-IP with the b2:µ2 hemicomplex. A previous study, now cited, had shown that the b2:µ2 hemicomplex could partially rescue null mutations of a in C. elegans (PMID: 23482940). We do not know how CCDC32 binds to the b2:µ2 hemicomplex and we did not detect these interactions using AlphaFold 3.0. However, these interactions could be indirect and involve the AAGAB chaperone. It is also likely, based on the results of Wan et al. (PMID: 39145939), that the binding is through the µ2 subunit rather than b2. As mentioned above, and in our Discussion, further studies are needed to define the complex and multi-faceted nature of CCDC32-AP2 interactions.

(4) The reported ability of CCDC32 to pull down AP2 beta is puzzling. Beta is not found in the CCDC32 interactome in two independent studies using 293 and HCT116 cells (BioPlex). In addition, clathrin is also absent in the interactome of CCDC32, which is difficult to reconcile with a proposed role in CCPs. Can the authors detect CCDC32 binding to clathrin?

Based on the studies of Wan et al. (PMID: 39145939), it is likely that CCDC32 binds to µ2, rather than to the b2 in the b2:µ2 hemicomplex. As to clathrin being absent from the CCDC32 pull down, this is as expected since the interactions of clathrin even with AP2 are weak in solution (as shown in Figure 5C, clathrin is not detected in our AP2 pull down) so as not to have spontaneous assembly of clathrin coats in the cytosol. Rather these interactions are strengthened by both the reduction in dimensionality that occurs on the membrane and by avidity of multivalent interactions. For example, Kirchausen reported that 2 AP2 complexes are required to recruit one clathrin triskelion to the PM.

(5) Figure 5B appears unusual-is this a chimera?

Figure 5B shows an internal insertion of the eGFP tag into an unstructured region in the AP2 hinge. As we have previously shown (PMID: 32657003), this construct, unique among other commonly used AP2 tags, is fully functional. We have rearranged the text in the Figure legend to make this clearer.

Figure 5C likely reflects a mixture of immature and mature AP2 adaptor complexes.

This is possible, but mature heterotetramers are by far the dominant species, otherwise the 4 subunits would not be immuno-precipitated at near stoichiometric levels with the a subunit. Near stoichiometric IP with antibodies to the a-AD have been shown by many others in many cell types.

(6) CCDC32 is reduced by about half in siRNA knockdown. Why not use CRISPR to completely eliminate CCDC32 expression?

Fortuitously, partial knockdown was essential to reveal this second function of CCDC32, as we have emphasized in our Discussion. Wan et al, used CRISPR to knockout CCDC32 and reveal its essential role as a AAGAB co-chaperone. In the complete absence of CCDC32 mature AP2 complexes fail to form. However, under our conditions of partial CCDC32 depletion, the expression of AP2 heterotetramers is unaffected revealing a second function of CCDC32 at early stages of CME. We expect that the co-chaperone function of CCDC32 is catalytic, while its role in CME is more structural; hence the different concentration dependencies, the former being less sensitive to KD than the latter. This is one reason that many researchers are turning to CRISPRi for whole genome perturbation studies as many proteins play multiple roles that can be masked in KO studies.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Yang et al. describes CCDC32 as a new clathrin mediated endocytosis (CME) accessory protein. The authors show that CCDC32 binds directly to AP2 via a small alpha helical region and cells depleted for this protein show defective CME. Finally, the authors show that the CCDC32 nonsense mutations found in patients with cardio-facial-neuro-developmental syndrome (CFNDS) disrupt the interaction of this protein to the AP2 complex. The results presented suggest that CCDC32 may act as both a chaperone (as recently published) and a structural component of the AP2 complex.

Strengths:

The conclusions presented are generally well supported by experimental data and the authors carefully point out the differences between their results and the results by Wan et al. (PNAS 2024).

Weaknesses:

The experiments regarding the role of CCDC32 in CFNDS still require some clarifications to make them clearer to scientists working on this disease. The authors fail to describe that the CCDC32 isoform they use in their studies is different from the one used when CFNDS patient mutations were described. This may create some confusion. Also, the authors did not discuss that the frame-shift mutations in patients may be leading to nonsense mediated decay.

As requested we have more clearly described our construct with regard to the human mutations and added the possibility of NMD in the context of the human mutations.

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

In this manuscript, Yang et al. characterize the endocytic accessory protein CCDC32, which has implications in cardio-facio-neuro-developmental syndrome (CFNDS). The authors clearly demonstrate that the protein CCDC32 has a role in the early stages of endocytosis, mainly through the interaction with the major endocytic adaptor protein AP2, and they identify regions taking part in this recognition. Through live cell fluorescence imaging and electron microscopy of endocytic pits, the authors characterize the lifetimes of endocytic sites, the formation rate of endocytic sites and pits and the invagination depth, in addition to transferrin receptor (TfnR) uptake experiments. Binding between CCDC32 and CCDC32 mutants to the AP2 alpha appendage domain is assessed by pull down experiments. While interaction between CCDC32 and the alpha appendage domain of AP2 is clearly described, a discussion of potential association with other AP2 domains would be beneficial to understand the impact of CCDC32 in endocytosis.

The reviewer is correct. That CCDC32 also interacts with other subunits of AP2, is evident from the findings of Wan et al. and by the fact that the CCDC32(D78-99) mutant efficiently co-IPs with the b2:µ2 hemicomplex. We expanded our discussion around this point. CCDC32 remains an, as yet, poorly characterized, but we now believe very interesting EAP worth further study.

Together, these experiments allow deriving a phenotype of CCDC32 knock-down and CCDC32 mutants within endocytosis, which is a very robust system, in which defects are not so easily detected. A mutation of CCDC32, mimicking CFNDS mutations, is also addressed in this study and shown to have endocytic defects.

In summary, the authors present a strong combination of techniques, assessing the impact of CCDC32 in clathrin mediated endocytosis and its binding to AP2.

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors):

(1) The authors must be clear about the differences between the CCDC32 isoform they used in their manuscript and the one used to describe the patient mutations. This could be done, for example, in the methods. This is essential for the capacity of other labs to reproduce, follow up and correctly cite these results.

We have added this information to the Methods.

(2) I believe the authors have misunderstood what nonsense mediated decay is. NMD occurs at the mRNA level and requires a full genome context to occur (introns and exons). The fact that a mutant protein is expressed normally from a construct by no means prove that it does not happen. I believe that adding the possibility of NMD occurring would enrich the discussion.

Thank you, we have now done more homework and have added this possibility into our discussion of the mutant phenotype. However, if a robust NMD mechanism resulted in a complete loss of CCDC42 protein, then the essential co-chaperone function reported by Wan et al, would result in complete loss of AP2. A more detailed characterization of the cellular phenotype of these mutations, including assessing the expression levels of AP2 would be informative.

Reviewer #3 (Recommendations for the authors):

- It is not clear what the authors mean by '~30s lifetime cohort' (line 159). They refer to Figure 2H, which shows the % of CCPs. Can the authors explain exactly what kind of tracks they used for this analysis, for example which lifetime variations were accepted? Do they refer to the cohorts in Figure S4? In Figure S4, the most frequent tracks have lifetimes < 20 s (in contrast to what is stated in the main text). Why was this cohort not used?

The ‘30s cohort’ refers to CCPs with lifetimes between 25-35s which encompasses the most abundant species in control cells and CCDC32 KD cells, as shown by the probability curves in Figure 2H. Given the large number of CCPs analyzed we still have large numbers for our analyses n=5998 and 4418, for control and siRNA treated conditions, respectively. Figure 2H shows the frequency of CCPs in cells treated with CCDC32 siRNA are shifted to shorter lifetimes. We have clarified this in the text.

- Figure S1: It is now clear, why the mutant versions of CCDC32 are not detected in this western blot. However, data that show the resistance of these proteins to siCCDC32 is still missing (S1 A is in the absence of siCCSC32 I assume, as the legend suggests). A western blot using an anti-GFP antibody, as the one used in Figure S1, after siRNA knock-known would provide clarity.

That these constructs all contain the same mutation in the siRNA target sequence gives us confidence that they are indeed resistant to siRNA.

- Note that the anti-CCDC32 antibody does not detect the eGFP-CCDC32(∆78-98) as well as full-length and is unable to detect eGFP-CCDC32(1-54)'. This phrase should belong to Figure S1 (B), not (A)

Corrected.

- The immunoprecipitations of CCDC32 and its mutants with AP2 and its subunits are partially confusing. In Figure 5, the authors show that CCDC32 interacts specifically with the alpha-AD, but not with the beta-AD of AP2. In Figure 6B and C, on the other hand, Co-IPs are shown also with the beta and the mu domain of AP2. This is understandable in the context of the full AP2. However, when interaction with the alpha domain (and sigma) is abolished through mutation of helix 78-98, why would beta and mu still interact, when the beta-AD cannot interact with CCDC32 on its own. Are there interaction sites expected outside the ADs in the beta or mu domains?

See responses to reviewer 1 above. This result likely reflects the co-chaperone activity of CCDC32 as reported by Wan et al it likely due to their reported interactions of CCDC32 with the µ2 subnit of b2:µ2 hemicomplexes.

- Figure S6 D, E and F: How much confidence do the authors have on the AlphaFold predictions? Have the same binding poses been obtained repeatedly by independent predictions?

We provide, with a color scale, the confidence score for each interaction, which is very high (>90%). Of course, this is still a prediction that will need to be verified by further structural studies as we have stated.

-

eLife Assessment

The manuscript presents a valuable finding that CCDC32, beyond its reported role in AP2 assembly, follows AP2 to the plasma membrane and regulates clathrin-coated pit assembly and dynamics. The authors further suggest that the alpha-helical region of CCDC32 interacts with AP2 via the alpha appendage domain to mediate this function. While live-cell and ultrastructural imaging data are solid, future biochemical studies will be needed to confirm the proposed CCDC32-AP2 interaction.

[Editors' note: this paper was reviewed by Review Commons.]

-

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

This is a revision of a manuscript previously submitted to Review Commons. The authors have partially addressed my comments, mainly by expanding the introduction and discussion sections. Sandy Schmid, a leading expert on the AP2 adaptor and CME, has been added as a co-corresponding author. The main message of the manuscript remains unchanged. Through overexpression of fluorescently tagged CCDC32, the authors propose that, in addition to its established role in AP2 assembly, CCDC32 also follows AP2 to the plasma membrane and regulates CCP maturation. The manuscript presents some interesting ideas, but there are still concerns regarding data inconsistencies and gaps in the evidence.

(1) eGFP-CCDC32 was expressed at 5-10 times higher levels than endogenous CCDC32. This high expression can artificially drive …

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

This is a revision of a manuscript previously submitted to Review Commons. The authors have partially addressed my comments, mainly by expanding the introduction and discussion sections. Sandy Schmid, a leading expert on the AP2 adaptor and CME, has been added as a co-corresponding author. The main message of the manuscript remains unchanged. Through overexpression of fluorescently tagged CCDC32, the authors propose that, in addition to its established role in AP2 assembly, CCDC32 also follows AP2 to the plasma membrane and regulates CCP maturation. The manuscript presents some interesting ideas, but there are still concerns regarding data inconsistencies and gaps in the evidence.

(1) eGFP-CCDC32 was expressed at 5-10 times higher levels than endogenous CCDC32. This high expression can artificially drive CCDC32 to the cell surface via binding to the alpha appendage domain (AD)-an interaction that may not occur under physiological conditions.

(2) Which region of CCDC32 mediates alpha AD binding? Strangely, the only mutant tested in this work, Δ78-98, still binds AP2, but shifts to binding only mu and beta. If the authors claim that CCDC32 is recruited to mature AP2 via the alpha AD, then a mutant deficient in alpha AD binding should not bind AP2 at all. Such a mutant is critical for establish the model proposed in this work.

(3) The concept of hemicomplexes is introduced abruptly. What is the evidence that such hemicomplexes exist? If CCDC32 binds to hemicomplexes, this must occur in the cytosol, as only mature AP2 tetramers are recruited to the plasma membrane. The authors state that CCDC32 binds the AD of alpha but not beta, so how can the Δ78-98 mutant bind mu and beta?

(4) The reported ability of CCDC32 to pull down AP2 beta is puzzling. Beta is not found in the CCDC32 interactome in two independent studies using 293 and HCT116 cells (BioPlex). In addition, clathrin is also absent in the interactome of CCDC32, which is difficult to reconcile with a proposed role in CCPs. Can the authors detect CCDC32 binding to clathrin?

(5) Figure 5B appears unusual-is this a chimera? Figure 5C likely reflects a mixture of immature and mature AP2 adaptor complexes.

(6) CCDC32 is reduced by about half in siRNA knockdown. Why not use CRISPR to completely eliminate CCDC32 expression?

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Yang et al. describes CCDC32 as a new clathrin mediated endocytosis (CME) accessory protein. The authors show that CCDC32 binds directly to AP2 via a small alpha helical region and cells depleted for this protein show defective CME. Finally, the authors show that the CCDC32 nonsense mutations found in patients with cardio-facial-neuro-developmental syndrome (CFNDS) disrupt the interaction of this protein to the AP2 complex. The results presented suggest that CCDC32 may act as both a chaperone (as recently published) and a structural component of the AP2 complex.

Strengths:

The conclusions presented are generally well supported by experimental data and the authors carefully point out the differences between their results and the results by Wan et al. (PNAS 2024).Weaknesses:

The experiments regarding the role …Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Yang et al. describes CCDC32 as a new clathrin mediated endocytosis (CME) accessory protein. The authors show that CCDC32 binds directly to AP2 via a small alpha helical region and cells depleted for this protein show defective CME. Finally, the authors show that the CCDC32 nonsense mutations found in patients with cardio-facial-neuro-developmental syndrome (CFNDS) disrupt the interaction of this protein to the AP2 complex. The results presented suggest that CCDC32 may act as both a chaperone (as recently published) and a structural component of the AP2 complex.

Strengths:

The conclusions presented are generally well supported by experimental data and the authors carefully point out the differences between their results and the results by Wan et al. (PNAS 2024).Weaknesses:

The experiments regarding the role of CCDC32 in CFNDS still require some clarifications to make them clearer to scientists working on this disease. The authors fail to describe that the CCDC32 isoform they use in their studies is different from the one used when CFNDS patient mutations were described. This may create some confusion. Also, the authors did not discuss that the frame-shift mutations in patients may be leading to nonsense mediated decay. -

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

In this manuscript, Yang et al. characterize the endocytic accessory protein CCDC32, which has implications in cardio-facio-neuro-developmental syndrome (CFNDS). The authors clearly demonstrate that the protein CCDC32 has a role in the early stages of endocytosis, mainly through the interaction with the major endocytic adaptor protein AP2, and they identify regions taking part in this recognition. Through live cell fluorescence imaging and electron microscopy of endocytic pits, the authors characterize the lifetimes of endocytic sites, the formation rate of endocytic sites and pits and the invagination depth, in addition to transferrin receptor (TfnR) uptake experiments. Binding between CCDC32 and CCDC32 mutants to the AP2 alpha appendage domain is assessed by pull down experiments. While interaction between …

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

In this manuscript, Yang et al. characterize the endocytic accessory protein CCDC32, which has implications in cardio-facio-neuro-developmental syndrome (CFNDS). The authors clearly demonstrate that the protein CCDC32 has a role in the early stages of endocytosis, mainly through the interaction with the major endocytic adaptor protein AP2, and they identify regions taking part in this recognition. Through live cell fluorescence imaging and electron microscopy of endocytic pits, the authors characterize the lifetimes of endocytic sites, the formation rate of endocytic sites and pits and the invagination depth, in addition to transferrin receptor (TfnR) uptake experiments. Binding between CCDC32 and CCDC32 mutants to the AP2 alpha appendage domain is assessed by pull down experiments. While interaction between CCDC32 and the alpha appendage domain of AP2 is clearly described, a discussion of potential association with other AP2 domains would be beneficial to understand the impact of CCDC32 in endocytosis.

Together, these experiments allow deriving a phenotype of CCDC32 knock-down and CCDC32 mutants within endocytosis, which is a very robust system, in which defects are not so easily detected. A mutation of CCDC32, mimicking CFNDS mutations, is also addressed in this study and shown to have endocytic defects.

In summary, the authors present a strong combination of techniques, assessing the impact of CCDC32 in clathrin mediated endocytosis and its binding to AP2.

-

Author response:

(1) General Statements

As you will see in our attached rebuttal to the reviewers, we have added several new experiments and revised manuscript to fully address their concerns.

(2) Point-by-point description of the revisions

Reviewer #1:

Evidence, reproducibility and clarity

Summary:

The manuscript by Yang et al. describes a new CME accessory protein. CCDC32 has been previously suggested to interact with AP2 and in the present work the authors confirm this interaction and show that it is a bona fide CME regulator. In agreement with its interaction with AP2, CCDC32 recruitment to CCPs mirrors the accumulation of clathrin. Knockdown of CCDC32 reduces the amount of productive CCPs, suggestive of a stabilisation role in early clathrin assemblies. Immunoprecipitation experiments mapped the interaction of CCDC42 to the …

Author response:

(1) General Statements

As you will see in our attached rebuttal to the reviewers, we have added several new experiments and revised manuscript to fully address their concerns.

(2) Point-by-point description of the revisions

Reviewer #1:

Evidence, reproducibility and clarity

Summary:

The manuscript by Yang et al. describes a new CME accessory protein. CCDC32 has been previously suggested to interact with AP2 and in the present work the authors confirm this interaction and show that it is a bona fide CME regulator. In agreement with its interaction with AP2, CCDC32 recruitment to CCPs mirrors the accumulation of clathrin. Knockdown of CCDC32 reduces the amount of productive CCPs, suggestive of a stabilisation role in early clathrin assemblies. Immunoprecipitation experiments mapped the interaction of CCDC42 to the α-appendage of the AP2 complex α-subunit. Finally, the authors show that the CCDC32 nonsense mutations found in patients with cardio-facial-neuro-developmental syndrome disrupt the interaction of this protein to the AP2 complex. The manuscript is well written and the conclusions regarding the role of CCDC32 in CME are supported by good quality data. As detailed below, a few improvements/clarifications are needed to reinforce some of the conclusions, especially the ones regarding CFNDS.

We thank the referee for their positive comments. In light of a recently published paper describing CCDC32 as a co-chaperone required for AP2 assembly (Wan et al., PNAS, 2024, see reviewer 2), we have added several additional experiments to address all concerns and consequently gained further insight into CCDC32-AP2 interactions and the important dual role of CCDC32 in regulating CME.

Major comments:

(1) Why did the protein could just be visualized at CCPs after knockdown of the endogenous protein? This is highly unusual, especially on stable cell lines. Could this be that the tag is interfering with the expressed protein function rendering it incapable of outcompeting the endogenous? Does this points to a regulated recruitment?

The reviewer is correct, this would be unusual; however, it is not the case. We misspoke in the text (although the figure legend was correct) these experiments were performed without siRNA knockdown and we can indeed detect eGFP-CCDC32 being recruited to CCPs in the presence of endogenous protein. Nonetheless, we repeated the experiment to be certain (see Author response image 1).

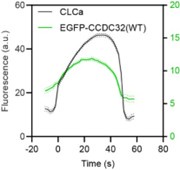

Author response image 1.

Cohort-averaged fluorescence intensity traces of CCPs (marked with mRuby-CLCa) and CCP-enriched eGFPCCDC32(FL).

(2) The disease mutation used in the paper does not correspond to the truncation found in patients. The authors use an 1-54 truncation, but the patients described in Harel et al. have frame shifts at the positions 19 (Thr19Tyrfs*12) and 64 (Glu64Glyfs*12), while the patient described in Abdalla et al. have the deletion of two introns, leading to a frameshift around amino acid 90. Moreover, to be precisely test the function of these disease mutations, one would need to add the extra amino acids generated by the frame shift. For example, as denoted in the mutation description in Harel et al., the frameshift at position 19 changes the Threonine 19 to a Tyrosine and ads a run of 12 extra amino acids (Thr19Tyrfs*12).

The label of the disease mutant p.(Thr19Tyrfs12) and p.(Glu64Glyfs12) is based on a 194aa polypeptide version of CCDC32 initiated at a nonconventional start site that contains a 9 aa peptide (VRGSCLRFQ) upstream of the N-terminus we show. Thus, we are indeed using the appropriate mutation site (see: https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/Q9BV29/entry). The reviewer is correct that we have not included the extra 12 aa in our construct; however as these residues are not present in the other CFNDS mutants, we think it unlikely that they contribute to the disease phenotype. Rather, as neither of the clinically observed mutations contain the 78-98 aa sequence required for AP2 binding and CME function, we are confident that this defect contributed to the disease. Thus, we are including the data on the CCDC32(1-54) mutant, as we believe these results provide a valuable physiological context to our studies.

(3) The frameshift caused by the CFNDS mutations (especially the one studied) will likely lead to nonsense mediated RNA decay (NMD). The frameshift is well within the rules where NMD generally kicks in. Therefore, I am unsure about the functional insights of expressing a diseaserelated protein which is likely not present in patients.

We thank the reviewer for bringing up this concern. However, as shown in new Figure S1, the mutant protein is expressed at comparable levels as the WT, suggesting that NMD is not occurring.

(4) Coiled coils generally form stable dimers. The typically hydrophobic core of these structures is not suitable for transient interactions. This complicates the interpretation of the results regarding the role of this region as the place where the interaction to AP2 occurs. If the coiled coil holds a stable CCDC32 dimer, disrupting this dimer could reduce the affinity to AP2 (by reduced avidity) to the actual binding site. A construct with an orthogonal dimeriser or a pulldown of the delta78-98 protein with of the GST AP2a-AD could be a good way to sort this issue.

We were unable to model a stable dimer (or other oligomer) of this protein with high confidence using Alphafold 3.0. Moreover, we were unable to detect endogenous CCDC32 coimmunoprecipitating with eGFP-CCDC32 (Fig. S6C). Thus, we believe that the moniker, based solely on the alpha-helical content of the protein is a misnomer. We have explained this in the main text.

Minor comments:

(1) The authors interchangeably use the term "flat CCPs" and "flat clathrin lattices". While these are indeed related, flat clathrin lattices have been also used to refer to "clathrin plaques". To avoid confusion, I suggest sticking to the term "flat CCPs" to refer to the CCPs which are in their early stages of maturation.

Agreed. Thank you for the suggestion. We have renamed these structures flat clathrin assemblies, as they do not acquire the curvature needed to classify them as pits, and do not grow to the size that would classify then as plaques.

Significance

General assessment:

CME drives the internalisation of hundreds of receptors and surface proteins in practically all tissues, making it an essential process for various physiological processes. This versatility comes at the cost of a large number of molecular players and regulators. To understand this complexity, unravelling all the components of this process is vital. The manuscript by Yang et al. gives an important contribution to this effort as it describes a new CME regulator, CCDC32, which acts directly at the main CME adaptor AP2. The link to disease is interesting, but the authors need to refine their experiments. The requirement for endogenous knockdown for recruitment of the tagged CCDC32 is unusual and requires further exploration.

Advance:

The increased frequency of abortive events presented by CCDC32 knockdown cells is very interesting, as it hints to an active mechanism that regulates the stabilisation and growth of clathrin coated pits. The exact way clathrin coated pits are stabilised is still an open question in the field.

Audience:

This is a basic research manuscript. However, given the essential role of CME in physiology and the growing number of CME players involved in disease, this manuscript can reach broader audiences.

We thank the referee for recognizing the ‘interesting’ advances our studies have made and for considering these studies as ‘an important contribution’ to ‘an essential process for various physiological processes’ and able ‘to reach broader audiences’. We have addressed and reconciled the reviewer’s concerns in our revised manuscript.

Field of expertise of the reviewer:

Clathrin mediated endocytosis, cell biology, microscopy, biochemistry.

Reviewer #2:

Evidence, reproducibility and clarity

In this manuscript, the authors demonstrate that CCDC32 regulates clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME). Some of the findings are consistent with a recent report by Wan et al. (2024 PNAS), such as the observation that CCDC32 depletion reduces transferrin uptake and diminishes the formation of clathrin-coated pits. The primary function of CCDC32 is to regulate AP2 assembly, and its depletion leads to AP2 degradation. However, this study did not examine AP2 expression levels. CCDC32 may bind to the appendage domain of AP2 alpha, but it also binds to the core domain of AP2 alpha.

We thank the reviewer for drawing our attention to the Wan et al. paper, that appeared while this work was under review. However, our in vivo data are not fully consistent with the report from Wan et al. The discrepancies reveal a dual function of CCDC32 in CME that was masked by complete knockout vs siRNA knockdown of the protein, and also likely affected by the position of the GFP-tag (C- vs N-terminal) on this small protein. Thus:

- Contrary to Wan et al., we do not detect any loss of AP2 expression (see new Figure S3A-B) upon siRNA knockdown. Most likely the ~40% residual CCDC32 present after siRNA knockdown is sufficient to fulfill its catalytic chaperone function but not its structural role in regulating CME beyond the AP2 assembly step.

- Contrary to Wan et al., we have shown that CCDC32 indeed interacts with intact AP2 complex (Figure S3C and 6B,C) showing that all 4 subunits of the AP2 complex co-IP with full length eGFP-CCDC32. Interestingly, whereas the full length CCDC32 pulls down the intact AP2 complex, co-IP of the ∆78-98 mutant retains its ability to pull down the β2-µ2 hemicomplex, its interactions with α:σ2 are severely reduced. While this result is consistent with the report of Wan et al that CCDC32 binds to the α:σ2 hemi-complex, it also suggests that the interactions between CCDC32 and AP2 are more complex and will require further studies.

- Contrary to Wan et al., we provide strong evidence that CCDC32 is recruited to CCPs. Interestingly, modeling with AlphaFold 3.0 identifies a highly probably interaction between alpha helices encoded by residues 66-91 on CCDC32 and residues 418-438 on α. The latter are masked by µ2-C in the closed confirmation of the AP2 core, but exposed in the open confirmation triggered by cargo binding, suggesting that CCDC32 might only bind to membrane-bound AP2.

Thus, our findings are indeed novel and indicate striking multifunctional roles for CCDC32 in CME, making the protein well worth further study.

(1) Besides its role in AP2 assembly, CCDC32 may potentially have another function on the membrane. However, there is no direct evidence showing that CCDC32 associates with the plasma membrane.

We disagree, our data clearly shows that CCDC32 is recruited to CCPs (Fig. 1B) and that CCPs that fail to recruit CCDC32 are short-lived and likely abortive (Fig. 1C). Wan et al. did not observe any colocalization of C-terminally tagged CCDC32 to CCPs, whereas we detect recruitment of our N-terminally tagged construct, which we also show is functional (Fig. 6F). Further, we have demonstrated the importance of the C-terminal region of CCDC32 in membrane association (see new Fig. S7). Thus, we speculate that a C-terminally tagged CCDC32 might not be fully functional. Indeed, SIM images of the C-terminally-tagged CCDC32 in Wan et al., show large (~100 nm) structures in the cytosol, which may reflect aggregation.

(2) CCDC32 binds to multiple regions on AP2, including the core domain. It is important to distinguish the functional roles of these different binding sites.

We have localized the AP2-ear binding region to residues 78-99 and shown these to be critical for the functions we have identified. As described above we now include data that are complementary to those of Wan et al. However, our data also clearly points to additional binding modalities. We agree that it will be important and map these additional interactions and identify their functional roles, but this is beyond the scope of this paper.

(3) AP2 expression levels should be examined in CCDC32 depleted cells. If AP2 is gone, it is not surprising that clathrin-coated pits are defective.

Agreed and we have confirmed this by western blotting (Figure S3A-B) and detect no reduction in levels of any of the AP2 subunits in CCDC32 siRNA knockdown cells. As stated above this could be due to residual CCDC32 present in the siRNA KD vs the CRISPR-mediated gene KO.

(4) If the authors aim to establish a secondary function for CCDC32, they need to thoroughly discuss the known chaperone function of CCDC32 and consider whether and how CCDC32 regulates a downstream step in CME.

Agreed. We have described the Wan et al paper, which came out while our manuscript was in review, in our Introduction. As described above, there are areas of agreement and of discrepancies, which are thoroughly documented and discussed throughout the revised manuscript.

(5) The quality of Figure 1A is very low, making it difficult to assess the localization and quantify the data.

The low signal:noise in Fig. 1A the reviewer is concerned about is due to a diffuse distribution of CCDC32 on the inner surface of the plasma membrane. We now, more explicitly describe this binding, which we believe reflects a specific interaction mediated by the C-terminus of CCDC32; thus the degree of diffuse membrane binding we observe follows: eGFP-CCDC32(FL)> eGFPCCDC32(∆78-98)>eGFP-CCDC32(1-54)~eGFP/background (see new Fig. S7). Importantly, the colocalization of CCDC32 at CCPs is confirmed by the dynamic imaging of CCPs (Fig 1B).

(6) In Figure 6, why aren't AP2 mu and sigma subunits shown?

Agreed. Not being aware of CCDC32’s possible dual role as a chaperone, we had assumed that the AP2 complex was intact. We have now added this data in Figure 6 B,C and Fig. S3C, as discussed above.

Page 5, top, this sentence is confusing: "their surface area (~17 x 10 nm2) remains significantly less than that required for the average 100 nm diameter CCV (~3.2 x 103 nm2)."

Thank you for the criticism. We have clarified the sentence and corrected a typo, which would definitely be confusing. The section now reads, “While the flat CCSs we detected in CCDC32 knockdown cells were significantly larger than in control cells (Fig. 4D, mean diameter of 147 nm vs. 127 nm, respectively), they are much smaller than typical long-lived flat clathrin lattices (d≥300 nm)(Grove et al., 2014). Indeed, the surface area of the flat CCSs that accumulate in CCDC32 KD cells (mean ~1.69 x 104 nm2) remains significantly less than the surface area of an average 100 nm diameter CCV (~3.14 x 104 nm2). Thus, we refer to these structures as ‘flat clathrin assemblies’ because they are neither curved ‘pits’ nor large ‘lattices’. Rather, the flat clathrin assemblies represent early, likely defective, intermediates in CCP formation.”

Significance

Overall, while this work presents some interesting ideas, it remains unclear whether CCDC32 regulates AP2 beyond the assembly step.

Our responses above argue that we have indeed established that CCDC32 regulates AP2 beyond the assembly step. We have also identified several discrepancies between our findings and those reported by Wan et al., most notably binding between CCDC32 and mature AP2 complexes and the AP2-dependent recruitment of CCDC32 to CCPs. It is possible that these discrepancies may be due to the position of the GFP tag (ours is N-terminal, theirs is C-terminal; we show that the N-terminal tagged CCDC32 rescues the knockdown phenotype, while Wan et al., do not provide evidence for functionality of the C-terminal construct).

Reviewer #3:

Evidence, reproducibility and clarity (Required):

In this manuscript, Yang et al. characterize the endocytic accessory protein CCDC32, which has implications in cardio-facio-neuro-developmental syndrome (CFNDS). The authors clearly demonstrate that the protein CCDC32 has a role in the early stages of endocytosis, mainly through the interaction with the major endocytic adaptor protein AP2, and they identify regions taking part in this recognition. Through live cell fluorescence imaging and electron microscopy of endocytic pits, the authors characterize the lifetimes of endocytic sites, the formation rate of endocytic sites and pits and the invagination depth, in addition to transferrin receptor (TfnR) uptake experiments. Binding between CCDC32 and CCDC32 mutants to the AP2 alpha appendage domain is assessed by pull down experiments. Together, these experiments allow deriving a phenotype of CCDC32 knock-down and CCDC32 mutants within endocytosis, which is a very robust system, in which defects are not so easily detected. A mutation of CCDC32, known to play a role in CFNDS, is also addressed in this study and shown to have endocytic defects.

We thank the reviewer for their positive remarks regarding the quality of our data and the strength of our conclusions.

In summary, the authors present a strong combination of techniques, assessing the impact of CCDC32 in clathrin mediated endocytosis and its binding to AP2, whereby the following major and minor points remain to be addressed:

- The authors show that CCDC32 depletion leads to the formation of brighter and static clathrin coated structures (Figure 2), but that these were only prevalent to 7.8% and masked the 'normal' dynamic CCPs. At the same time, the authors show that the absence of CCDC32 induces pits with shorter life times (Figure 1 and Figure 2), the 'majority' of the pits.

Clarification is needed as to how the authors arrive at these conclusions and these numbers. The authors should also provide (and visualize) the corresponding statistics. The same statement is made again later on in the manuscript, where the authors explain their electron microscopy data. Was the number derived from there?

These points are critical to understanding CCDC32's role in endocytosis and is key to understanding the model presented in Figure 8. The numbers of how many pits accumulate in flat lattices versus normal endocytosis progression and the actual time scales could be included in this model and would make the figure much stronger.

Thank you for these comments. We understand the paradox between the visual impression and the reality of our dynamic measurements. We have been visually misled by this in previous work (Chen et al., 2020), which emphasizes the importance of unbiased image analysis afforded to us through the well-documented cmeAnalysis pipeline, developed by us (Aguet et al., 2013) and now used by many others (e.g. (He et al., 2020)).

The % of static structures was not derived from electron microscopy data, but quantified using cmeAnalysis, which automatedly provides the lifetime distribution of CCPs. We have now clarified this in the manuscript and added a histogram (Fig. S4) quantifying the fraction of CCPs in lifetime cohorts <20s, 21-60s, 61-100s, 101-150s and >150s (static).

- In relation to the above point, the statistics of Figure 2E-G and the analysis leading there should also be explained in more detail: For example, what are the individual points in the plot (also in Figures 6G and 7G)? The authors should also use a few phrases to explain software they use, for example DASC, in the main text.

Each point in these bar graphs represents a movie, where n≥12. These details have been added to the respective figure legend. We have also added a brief description of DASC analysis in the text.

- There are several questions related to the knock-down experiments that need to be addressed:

Firstly, knock-down of CCDC32 does not seem to be very strong (Figure S2B). Can the level of knock-down be quantified?

We have now quantified the KD efficiency. It is ~60%. This turns out to be fortuitous (see responses to reviewer 2), as a recent publication, which came out after we completed our study, has shown by CRISPR-mediated knockout, that CCD32 also plays an essential chaperone function required for AP2 assembly. We do not see any reduction in AP2 levels or its complex formation under our conditions (see new Supplemental Figure S3), which suggests that the effects of CCDC32 on CCP dynamics are more sensitive to CCDC32 concentration than its roles as a chaperone. Our phenotypes would have been masked by more efficient depletion of CCDC32.

In page 6 it is indicated that the eGFP-CCDC32(1-54) and eGFP-CCDC32(∆78-98) constructs are siRNA-resistant. However in Fig S2B, these proteins do not show any signal in the western blot, so it is not clear if they are expressed or simply not detected by the antibody. The presence of these proteins after silencing endogenous CCDC32 needs to be confirmed to support Figures 6 and Figures 7, which critically rely on the presence of the CCDC32 mutants.

Unfortunately, the C-terminally truncated CCDC32 proteins are not detected because they lack the antibody epitope, indeed even the ∆78-98 deletion is poorly detected (compare the GFP blot in new S1A with the anti-CCDC32 blot in S1B). However, these constructs contain the same siRNA-resistance mutation as the full length protein. That they are expressed and siRNA resistant can be seen in Fig. S2A (now Fig. S1A) blotting for GFP.

In Figures 6 and 7, siRNA knock-down of CCDC32 is only indicated for sub-figures F to G. Is this really the case? If not, the authors should clarify. The siRNA knock-down in Figure 1 is also only mentioned in the text, not in the figure legend. The authors should pay attention to make their figure legends easy to understand and unambiguous.

No, it is not the case. Thank you for pointing out the uncertainty. We have added these details to the Figure legends and checked all Figure legends to ensure that they clearly describe the data shown.

- It is not exactly clear how the curves in Figure 3C (lower panel) on the invagination depth were obtained. Can the authors clarify this a bit more? For example, what are kT and kE in Figure 3A? What is I0? And how did the authors derive the logarithmic function used to quantify the invagination depth? In the main text, the authors say that the traces were 'logarithmically transformed'. This is not a technical term. The authors should refer to the actual equation used in the figure.

This analysis was developed by the Kirchhausen lab (Saffarian and Kirchhausen, 2008). We have added these details and reference them in the Figure legend and in the text. We also now use the more accurate descriptor ‘log-transformed’.

- In the discussion, the claim 'The resulting dysregulation of AP2 inhibits CME, which further results in the development of CFNDS.' is maybe a bit too strong of a statement. Firstly, because the authors show themselves that CME is perturbed, but by no means inhibited. Secondly, the molecular link to CFNDS remains unclear. Even though CCDC32 mutants seem to be responsible for CFNDS and one of the mutant has been shown in this study to have a defect in endocytosis and AP2 binding, a direct link between CCDC32's function in endocytosis and CFNDS remains elusive. The authors should thus provide a more balanced discussion on this topic.

We have modified and softened our conclusions, which now read that the phenotypes we see likely “contribute to” rather than “cause” the disease.

- In Figure S1, the authors annotate the presence of a coiled-coil domain, which they also use later on in the manuscript to generate mutations. Could the authors specify (and cite) where and how this coiled-coil domain has been identified? Is this predicted helix indeed a coiled-coil domain, or just a helix, as indicated by the authors in the discussion?

See response to Reviewer 1, point 4. We have changed this wording to alpha-helix. The ‘coiled-coil’ reference is historical and unlikely a true reflection of CCDC32 structure. AlphaFold 3.0 predictions were unable to identify with certainly any coiled-coil structures, even if we modelled potential dimers or trimers; and we find no evidence of dimerization of CCDC32 in vivo. We have clarified this in the text.

Minor comments

- In general, a more detailed explanation of the microscopy techniques used and the information they report would be beneficial to provide access to the article also to non-expert readers in the field. This concerns particularly the analysis methods used, for example:

How were the cohort-averaged fluorescence intensity and lifetime traces obtained?

How do the tools cmeAnalysis and DASC work? A brief explanation would be helpful.

We have expanded Methods to add these details, and also described them in the main text.

- The axis label of Figure 2B is not quite clear. What does 'TfnR uptake % of surface bound' mean? Maybe the authors could explain this in more detail in the figure legend? Is the drop in uptake efficiency also accessible by visual inspection of the images? It would be interesting to see that.

This is a standard measure of CME efficiency. 'TfnR uptake % of surface bound' = Internalized TfnR/Surface bound TfnR. Again, images may be misleading as defects in CME lead to increased levels of TfnR on the cell surface, which in turn would result in more Tfn uptake even if the rate of CME is decreased.

- Figure 4: How is the occupancy of CCPs in the plasma membrane measured? What are the criteria used to divide CCSs into Flat, Dome or Sphere categories?

We have expanded Methods to add these details. Based on the degree of invagination, the shapes of CCSs were classified as either: flat CCSs with no obvious invagination; dome-shaped CCSs that had a hemispherical or less invaginated shape with visible edges of the clathrin lattice; and spherical CCSs that had a round shape with the invisible edges of clathrin lattice in 2D projection images. In most cases, the shapes were obvious in 2D PREM images. In uncertain cases, the degree of CCS invagination was determined using images tilted at ±10–20 degrees. The area of CCSs were measured using ImageJ and used for the calculation of the CCS occupancy on the plasma membrane.

- Figure 5B: Can the authors explain, where exactly the GFP was engineered into AP2 alpha? This construct does not seem to be explained in the methods section.

We have added this information. The construct, which corresponds to an insertion of GFP into the flexible hinge region of AP2, at aa649, was first described by (Mino et al., 2020) and shown to be fully functional. This information has been added to the Methods section.

- Figure S1B: The authors should indicate the colour code used for the structural model.

We have expanded our structural modeling using AlphaFold 3.0 in light of the recent publication suggesting the CCDC32 interacts with the µ2 subunit and does not bind full length AP2. These results are described in the text. The color coding now reflects certainty values given by AlphaFold 3.0 (Fig. S6B, D).

- The list of primers referred to in the materials and methods section does not exist. There is a Table S1, but this contains different data. The actual Table S1 is not referenced in the main text. This should be done.

We apologize for this error. We have now added this information in Table S2.

Significance (Required):

In this study, the authors analyse a so-far poorly understood endocytic accessory protein, CCDC32, and its implication for endocytosis. The experimental tool set used, allowing to quantify CCP dynamics and invagination is clearly a strength of the article that allows assessing the impact of an accessory protein towards the endocytic uptake mechanism, which is normally very robust towards mutations. Only through this detailed analysis of endocytosis progression could the authors detect clear differences in the presence and absence of CCDC32 and its mutants. If the above points are successfully addressed, the study will provide very interesting and highly relevant work allowing a better understanding of the early phases in CME with implication for disease.

The study is thus of potential interest to an audience interested in CME, in disease and its molecular reasons, as well as for readers interested in intrinsically disordered proteins to a certain extent, claiming thus a relatively broad audience. The presented results may initiate further studies of the so-far poorly understood and less well known accessory protein CCDC32.

We thank the reviewer for their positive comments on the significance of our findings and the importance of our detailed phenotypic analysis made possible by quantitative live cell microscopy. We also believe that our new structural modeling of CCDC32 and our findings of complex and extensive interactions with AP2 make the reviewers point regarding intrinsically disordered proteins even more interesting and relevant to a broad audience. We trust that our revisions indeed address the reviewer’s concerns.

The field of expertise of the reviewer is structural biology, biochemistry and clathrin mediated endocytosis. Expertise in cell biology is rather superficial.

References:

Aguet, F., Costin N. Antonescu, M. Mettlen, Sandra L. Schmid, and G. Danuser. 2013. Advances in Analysis of Low Signal-to-Noise Images Link Dynamin and AP2 to the Functions of an Endocytic Checkpoint. Developmental Cell. 26:279-291.

Chen, Z., R.E. Mino, M. Mettlen, P. Michaely, M. Bhave, D.K. Reed, and S.L. Schmid. 2020. Wbox2: A clathrin terminal domain–derived peptide inhibitor of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Journal of Cell Biology. 219.

Grove, J., D.J. Metcalf, A.E. Knight, S.T. Wavre-Shapton, T. Sun, E.D. Protonotarios, L.D. Griffin, J. Lippincott-Schwartz, and M. Marsh. 2014. Flat clathrin lattices: stable features of the plasma membrane. Mol Biol Cell. 25:3581-3594.

He, K., E. Song, S. Upadhyayula, S. Dang, R. Gaudin, W. Skillern, K. Bu, B.R. Capraro, I. Rapoport, I. Kusters, M. Ma, and T. Kirchhausen. 2020. Dynamics of Auxilin 1 and GAK in clathrinmediated traffic. J Cell Biol. 219.

Mino, R.E., Z. Chen, M. Mettlen, and S.L. Schmid. 2020. An internally eGFP-tagged α-adaptin is a fully functional and improved fiduciary marker for clathrin-coated pit dynamics. Traffic. 21:603-616.

Saffarian, S., and T. Kirchhausen. 2008. Differential evanescence nanometry: live-cell fluorescence measurements with 10-nm axial resolution on the plasma membrane. Biophys J. 94:23332342.

-

-

Note: This response was posted by the corresponding author to Review Commons. The content has not been altered except for formatting.

Learn more at Review Commons

Reply to the reviewers

Reviewer #1

Evidence, reproducibility and clarity

Summary: The manuscript by Yang et al. describes a new CME accessory protein. CCDC32 has been previously suggested to interact with AP2 and in the present work the authors confirm this interaction and show that it is a bona fide CME regulator. In agreement with its interaction with AP2, CCDC32 recruitment to CCPs mirrors the accumulation of clathrin. Knockdown of CCDC32 reduces the amount of productive CCPs, suggestive of a stabilisation role in early clathrin assemblies. Immunoprecipitation experiments mapped the interaction of CCDC42 to the α-appendage of the AP2 complex α-subunit. Finally, the …

Note: This response was posted by the corresponding author to Review Commons. The content has not been altered except for formatting.

Learn more at Review Commons

Reply to the reviewers

Reviewer #1

Evidence, reproducibility and clarity

Summary: The manuscript by Yang et al. describes a new CME accessory protein. CCDC32 has been previously suggested to interact with AP2 and in the present work the authors confirm this interaction and show that it is a bona fide CME regulator. In agreement with its interaction with AP2, CCDC32 recruitment to CCPs mirrors the accumulation of clathrin. Knockdown of CCDC32 reduces the amount of productive CCPs, suggestive of a stabilisation role in early clathrin assemblies. Immunoprecipitation experiments mapped the interaction of CCDC42 to the α-appendage of the AP2 complex α-subunit. Finally, the authors show that the CCDC32 nonsense mutations found in patients with cardio-facial-neuro-developmental syndrome disrupt the interaction of this protein to the AP2 complex. The manuscript is well written and the conclusions regarding the role of CCDC32 in CME are supported by good quality data. As detailed below, a few improvements/clarifications are needed to reinforce some of the conclusions, especially the ones regarding CFNDS.

Response: We thank the referee for their positive comments. In light of a recently published paper describing CCDC32 as a co-chaperone required for AP2 assembly (Wan et al., PNAS, 2024, see reviewer 2), we have added several additional experiments to address all concerns and consequently gained further insight into CCDC32-AP2 interactions and the important dual role of CCDC32 in regulating CME.

Major comments:

- Why did the protein could just be visualized at CCPs after knockdown of the endogenous protein? This is highly unusual, especially on stable cell lines. Could this be that the tag is interfering with the expressed protein function rendering it incapable of outcompeting the endogenous? Does this points to a regulated recruitment?

Response: The reviewer is correct, this would be unusual; however, it is not the case. We misspoke in the text (although the figure legend was correct) these experiments were performed without siRNA knockdown and we can indeed detect eGFP-CCDC32 being recruited to CCPs in the presence of endogenous protein. Nonetheless, we repeated the experiment to be certain.

- The disease mutation used in the paper does not correspond to the truncation found in patients. The authors use an 1-54 truncation, but the patients described in Harel et al. have frame shifts at the positions 19 (Thr19Tyrfs*12) and 64 (Glu64Glyfs*12), while the patient described in Abdalla et al. have the deletion of two introns, leading to a frameshift around amino acid 90. Moreover, to be precisely test the function of these disease mutations, one would need to add the extra amino acids generated by the frame shift. For example, as denoted in the mutation description in Harel et al., the frameshift at position 19 changes the Threonine 19 to a Tyrosine and ads a run of 12 extra amino acids (Thr19Tyrfs*12).

Response: The label of the disease mutant p.(Thr19Tyrfs∗12) and p.(Glu64Glyfs∗12) is based on a 194aa polypeptide version of CCDC32 initiated at a nonconventional start site that contains a 9 aa peptide (VRGSCLRFQ) upstream of the N-terminus we show. Thus, we are indeed using the appropriate mutation site (see: https://www.uniprot.org/uniprotkb/Q9BV29/entry). The reviewer is correct that we have not included the extra 12 aa in our construct; however as these residues are not present in the other CFNDS mutants, we think it unlikely that they contribute to the disease phenotype. Rather, as neither of the clinically observed mutations contain the 78-98 aa sequence required for AP2 binding and CME function, we are confident that this defect contributed to the disease. Thus, we are including the data on the CCDC32(1-54) mutant, as we believe these results provide a valuable physiological context to our studies.

- The frameshift caused by the CFNDS mutations (especially the one studied) will likely lead to nonsense mediated RNA decay (NMD). The frameshift is well within the rules where NMD generally kicks in. Therefore, I am unsure about the functional insights of expressing a disease-related protein which is likely not present in patients.

Response: We thank the reviewer for bringing up this concern. However, as shown in new Figure S1, the mutant protein is expressed at comparable levels as the WT, suggesting that NMD is not occurring.

- Coiled coils generally form stable dimers. The typically hydrophobic core of these structures is not suitable for transient interactions. This complicates the interpretation of the results regarding the role of this region as the place where the interaction to AP2 occurs. If the coiled coil holds a stable CCDC32 dimer, disrupting this dimer could reduce the affinity to AP2 (by reduced avidity) to the actual binding site. A construct with an orthogonal dimeriser or a pulldown of the delta78-98 protein with of the GST AP2a-AD could be a good way to sort this issue.

Response: We were unable to model a stable dimer (or other oligomer) of this protein with high confidence using Alphafold 3.0. Moreover, we were unable to detect endogenous CCDC32 co-immunoprecipitating with eGFP-CCDC32 (Fig. S6C). Thus, we believe that the moniker, based solely on the alpha-helical content of the protein is a misnomer. We have explained this in the main text.

Minor comments:

- The authors interchangeably use the term "flat CCPs" and "flat clathrin lattices". While these are indeed related, flat clathrin lattices have been also used to refer to "clathrin plaques". To avoid confusion, I suggest sticking to the term "flat CCPs" to refer to the CCPs which are in their early stages of maturation.

Response: Agreed. Thank you for the suggestion. We have renamed these structures flat clathrin assemblies, as they do not acquire the curvature needed to classify them as pits, and do not grow to the size that would classify then as plaques.

Significance

General assessment: CME drives the internalisation of hundreds of receptors and surface proteins in practically all tissues, making it an essential process for various physiological processes. This versatility comes at the cost of a large number of molecular players and regulators. To understand this complexity, unravelling all the components of this process is vital. The manuscript by Yang et al. gives an important contribution to this effort as it describes a new CME regulator, CCDC32, which acts directly at the main CME adaptor AP2. The link to disease is interesting, but the authors need to refine their experiments. The requirement for endogenous knockdown for recruitment of the tagged CCDC32 is unusual and requires further exploration.

Advance: The increased frequency of abortive events presented by CCDC32 knockdown cells is very interesting, as it hints to an active mechanism that regulates the stabilisation and growth of clathrin coated pits. The exact way clathrin coated pits are stabilised is still an open question in the field.

Audience: This is a basic research manuscript. However, given the essential role of CME in physiology and the growing number of CME players involved in disease, this manuscript can reach broader audiences.

Response: We thank the referee for recognizing the 'interesting' advances our studies have made and for considering these studies as 'an important contribution' to 'an essential process for various physiological processes' and able 'to reach broader audiences'. We have addressed and reconciled the reviewer's concerns in our revised manuscript.

Field of expertise of the reviewer: Clathrin mediated endocytosis, cell biology, microscopy, biochemistry.

Reviewer #2

Evidence, reproducibility and clarity

In this manuscript, the authors demonstrate that CCDC32 regulates clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME). Some of the findings are consistent with a recent report by Wan et al. (2024 PNAS), such as the observation that CCDC32 depletion reduces transferrin uptake and diminishes the formation of clathrin-coated pits. The primary function of CCDC32 is to regulate AP2 assembly, and its depletion leads to AP2 degradation. However, this study did not examine AP2 expression levels. CCDC32 may bind to the appendage domain of AP2 alpha, but it also binds to the core domain of AP2 alpha. Overall, while this work presents some interesting ideas, it remains unclear whether CCDC32 regulates AP2 beyond the assembly step.

Response: We thank the reviewer for drawing our attention to the Wan et al. paper, that appeared while this work was under review. However, our in vivo data are not fully consistent with the report from Wan et al. The discrepancies reveal a dual function of CCDC32 in CME that was masked by complete knockout vs siRNA knockdown of the protein, and also likely affected by the position of the GFP-tag (C- vs N-terminal) on this small protein. Thus:

- Contrary to Wan et al., we do not detect any loss of AP2 expression (see new Figure S3A-B) upon siRNA knockdown. Most likely the ~40% residual CCDC32 present after siRNA knockdown is sufficient to fulfill its catalytic chaperone function but not its structural role in regulating CME beyond the AP2 assembly step.

- Contrary to Wan et al., we have shown that CCDC32 indeed interacts with intact AP2 complex (Figure S3C and 6B,C) showing that all 4 subunits of the AP2 complex co-IP with full length eGFP-CCDC32. Interestingly, whereas the full length CCDC32 pulls down the intact AP2 complex, co-IP of the ∆78-98 mutant retains its ability to pull down the b2-µ2 hemicomplex, its interactions with α:σ2 are severely reduced. While this result is consistent with the report of Wan et al that CCDC32 binds to the α:σ2 hemi-complex, it also suggests that the interactions between CCDC32 and AP2 are more complex and will require further studies.

- Contrary to Wan et al., we provide strong evidence that CCDC32 is recruited to CCPs. Interestingly, modeling with AlphaFold 3.0 identifies a highly probably interaction between alpha helices encoded by residues 66-91 on CCDC32 and residues 418-438 on a. The latter are masked by µ2-C in the closed confirmation of the AP2 core, but exposed in the open confirmation triggered by cargo binding, suggesting that CCDC32 might only bind to membrane-bound AP2. Thus, our findings are indeed novel and indicate striking multifunctional roles for CCDC32 in CME, making the protein well worth further study.

Besides its role in AP2 assembly, CCDC32 may potentially have another function on the membrane. However, there is no direct evidence showing that CCDC32 associates with the plasma membrane.

Response: We disagree, our data clearly shows that CCDC32 is recruited to CCPs (Fig. 1B) and that CCPs that fail to recruit CCDC32 are short-lived and likely abortive (Fig. 1C). Wan et al. did not observe any colocalization of C-terminally tagged CCDC32 to CCPs, whereas we detect recruitment of our N-terminally tagged construct, which we also show is functional (Fig. 6F). Further, we have demonstrated the importance of the C-terminal region of CCDC32 in membrane association (see new Fig. S7). Thus, we speculate that a C-terminally tagged CCDC32 might not be fully functional. Indeed, SIM images of the C-terminally-tagged CCDC32 in Wan et al., show large (~100 nm) structures in the cytosol, which may reflect aggregation.

CCDC32 binds to multiple regions on AP2, including the core domain. It is important to distinguish the functional roles of these different binding sites.

Response: We have localized the AP2-ear binding region to residues 78-99 and shown these to be critical for the functions we have identified. As described above we now include data that are complementary to those of Wan et al. However, our data also clearly points to additional binding modalities. We agree that it will be important and map these additional interactions and identify their functional roles, but this is beyond the scope of this paper.

AP2 expression levels should be examined in CCDC32 depleted cells. If AP2 is gone, it is not surprising that clathrin-coated pits are defective.

Response: Agreed and we have confirmed this by western blotting (Figure S3A-B) and detect no reduction in levels of any of the AP2 subunits in CCDC32 siRNA knockdown cells. As stated above this could be due to residual CCDC32 present in the siRNA KD vs the CRISPR-mediated gene KO.

If the authors aim to establish a secondary function for CCDC32, they need to thoroughly discuss the known chaperone function of CCDC32 and consider whether and how CCDC32 regulates a downstream step in CME.

Response: Agreed. We have described the Wan et al paper, which came out while our manuscript was in review, in our Introduction. As described above, there are areas of agreement and of discrepancies, which are thoroughly documented and discussed throughout the revised manuscript.

The quality of Figure 1A is very low, making it difficult to assess the localization and quantify the data.

Response: The low signal:noise in Fig. 1A the reviewer is concerned about is due to a diffuse distribution of CCDC32 on the inner surface of the plasma membrane. We now, more explicitly describe this binding, which we believe reflects a specific interaction mediated by the C-terminus of CCDC32; thus the degree of diffuse membrane binding we observe follows: eGFP-CCDC32(FL)> eGFP-CCDC32(∆78-98)>eGFP-CCDC32(1-54)~eGFP/background (see new Fig. S7). Importantly, the colocalization of CCDC32 at CCPs is confirmed by the dynamic imaging of CCPs (Fig 1B).

In Figure 6, why aren't AP2 mu and sigma subunits shown?

Response: Agreed. Not being aware of CCDC32's possible dual role as a chaperone, we had assumed that the AP2 complex was intact. We have now added this data in Figure 6 B,C and Fig. S3C, as discussed above.

Page 5, top, this sentence is confusing: "their surface area (~17 x 10 nm2) remains significantly less than that required for the average 100 nm diameter CCV (~3.2 x 103 nm2)."