Forward genetics in C. elegans reveals genetic adaptations to polyunsaturated fatty acid deficiency

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

eLife Assessment

This fundamental study investigates the role of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in physiology and membrane biology, using a unique model to perform a thorough genetic screen that demonstrates that PUFA synthesis defects cannot be compensated for by mutations in other pathways. These findings are supported by compelling evidence from a high quality genetic screen, functional validation of their hits, and lipid analyses. This study will appeal to researchers in membrane biology, lipid metabolism, and C. elegans genetics.

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) are essential for mammalian health and function as membrane fluidizers and precursors for signaling lipids, though the primary essential function of PUFAs within organisms has not been established. Unlike mammals who cannot endogenously synthesize PUFAs, C. elegans can de novo synthesize PUFAs starting with the Δ12 desaturase FAT-2, which introduces a second double bond to monounsaturated fatty acids to generate the PUFA linoleic acid. FAT-2 desaturation is essential for C. elegans survival since fat-2 null mutants are non-viable; the near-null fat-2(wa17 ) allele synthesizes only small amounts of PUFAs and produces extremely sick worms. Using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP), we found that the fat-2(wa17 ) mutant has rigid membranes and can be efficiently rescued by dietarily providing various PUFAs, but not by fluidizing treatments or mutations. With the aim of identifying mechanisms that compensate for PUFA-deficiency, we performed a forward genetics screen to isolate novel fat-2(wa17 ) suppressors and identified four internal mutations within fat-2 and six mutations within the HIF-1 pathway. The suppressors increase PUFA levels in fat-2(wa17 ) mutant worms and additionally suppress the activation of the daf-16 , UPR er and UPR mt stress response pathways that are active in fat-2(wa17 ) worms. We hypothesize that the six HIF-1 pathway mutations, found in egl-9 , ftn-2 , and hif-1, all converge on raising Fe 2+ levels and in this way boost desaturase activity, including that of the fat-2(wa17 ) allele. We conclude that PUFAs cannot be genetically replaced and that the only genetic mechanism that can alleviate PUFA-deficiency do so by increasing PUFA levels.

Article activity feed

-

-

-

eLife Assessment

This fundamental study investigates the role of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in physiology and membrane biology, using a unique model to perform a thorough genetic screen that demonstrates that PUFA synthesis defects cannot be compensated for by mutations in other pathways. These findings are supported by compelling evidence from a high quality genetic screen, functional validation of their hits, and lipid analyses. This study will appeal to researchers in membrane biology, lipid metabolism, and C. elegans genetics.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

This study addresses the roles of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in animal physiology and membrane function. A C. elegans strain carrying the fat-2(wa17) mutation possesses a very limited ability to synthesize PUFAs and there is no dietary input because the E. coli diet consumed by lab grown C. elegans does not contain any PUFAs. The fat-2 mutant strain was characterized to confirm that the worms grow slowly, have rigid membranes, and have a constitutive mitochondrial stress response. The authors showed that chemical treatments or mutations known to increase membrane fluidity did not rescue growth defects. A thorough genetic screen was performed to identify genetic changes to compensate for the lack of PUFAs. The newly isolated suppressor mutations that compensated for FAT-2 growth defects …

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

This study addresses the roles of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in animal physiology and membrane function. A C. elegans strain carrying the fat-2(wa17) mutation possesses a very limited ability to synthesize PUFAs and there is no dietary input because the E. coli diet consumed by lab grown C. elegans does not contain any PUFAs. The fat-2 mutant strain was characterized to confirm that the worms grow slowly, have rigid membranes, and have a constitutive mitochondrial stress response. The authors showed that chemical treatments or mutations known to increase membrane fluidity did not rescue growth defects. A thorough genetic screen was performed to identify genetic changes to compensate for the lack of PUFAs. The newly isolated suppressor mutations that compensated for FAT-2 growth defects included intergenic suppressors in the fat-2 gene, as well as constitutive mutations in the hypoxia sensing pathway components EGL-9 and HIF-1, and loss of function mutations in ftn-2, a gene encoding the iron storage protein ferritin. Taken together, these mutations lead to the model that increased intracellular iron, an essential cofactor for fatty acid desaturases, allows the minimally functional FAT-2(wa17) enzyme to be more active, resulting in increased desaturation and increased PUFA synthesis.

Strengths:

(1) This study provides new information further characterizing fat-2 mutants. The authors measured increased rigidity of membranes compared to wild type worms, however this rigidity is not able to be rescued with other fluidity treatments such as detergent or mutants. Rescue was only achieved with polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation.

(2) A very thorough genetic suppressor screen was performed. In addition to some internal fat-2 compensatory mutations, the only changes in pathways identified that are capable of compensating for deficient PUFA synthesis was the hypoxia pathway and the iron storage protein ferritin. Suppressor mutations included an egl-9 mutation that constitutively activates HIF-1, and Gain of function mutations in hif-1 that are dominant. This increased activity of HIF conferred by specific egl-9 and hif-1 mutations lead to decreased expression of ftn-2. Indeed, loss of ftn-2 leads to higher intracellular iron. The increased iron apparently makes the FAT-2 fatty acid desaturase enzyme more active, allowing for the production of more PUFAs.

(3) The mutations isolated in the suppressor screen show that the only mutations able to compensate for lack of PUFAs were ones that increased PUFA synthesis by the defective FAT-2 desaturase, thus demonstrating the essential need for PUFAs that cannot be overcome by changes in other pathways. This is a very novel study, taking advantage of genetic analysis of C. elegans, and it confirms the observations in humans that certain essential PUFAs are required for growth and development.

(4) Overall, the paper is well written, and the experiments were carried out carefully and thoroughly. The conclusions are well supported by the results.

Weaknesses:

Overall, there are not many weaknesses. The main one I noticed is that the lipidomic analysis shown in Figs 3C, 7C, S1 and S3. While these data are an essential part of the analysis and provide strong evidence for the conclusions of the study, it is unfortunate that the methods used did not enable the distinction between two 18:1 isomers. These two isomers of 18:1 are important in C. elegans biology, because one is a substrate for FAT-2 (18:1n-9, oleic acid) and the other is not (18:1n-7, cis vaccenic acid). Although rarer in mammals, cis-vaccenic acid is the most abundant fatty acid in C. elegans and is likely the most important structural MUFA. The measurement of these two isomers is not essential for the conclusions of the study.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors use a genetic screen in C. elegans to investigate the physiological roles of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). They screen for mutations that rescue fat-2 mutants, which have strong reductions in PUFAs. As a result, either mutations in fat-2 itself or mutations in genes involved in the HIF-1 pathway were found to rescue fat-2 mutants. Mutants in the HIF-1 pathway rescue fat-2 mutants by boosting their catalytic activity (via upregulated Fe2+). Thus, the authors show that in the context of fat-2 mutation, the sole genetic means to rescue PUFA insufficiency is to restore PUFA levels.

Strengths:

As C. elegans can produce PUFAs de novo as essential lipids, the genetic model is well-suited to study the fundamental roles of PUFAs. The genetic screen finds mutations in convergent pathways, …

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors use a genetic screen in C. elegans to investigate the physiological roles of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). They screen for mutations that rescue fat-2 mutants, which have strong reductions in PUFAs. As a result, either mutations in fat-2 itself or mutations in genes involved in the HIF-1 pathway were found to rescue fat-2 mutants. Mutants in the HIF-1 pathway rescue fat-2 mutants by boosting their catalytic activity (via upregulated Fe2+). Thus, the authors show that in the context of fat-2 mutation, the sole genetic means to rescue PUFA insufficiency is to restore PUFA levels.

Strengths:

As C. elegans can produce PUFAs de novo as essential lipids, the genetic model is well-suited to study the fundamental roles of PUFAs. The genetic screen finds mutations in convergent pathways, suggesting that it has reached near-saturation. The authors extensively validate the results of the screening and provide sufficient mechanistic insights to show how PUFA levels are restored in HIF-1 pathway mutants. As many of the mutations found to rescue fat-2 mutants are of gain-of-function, it is unlikely that similar discoveries could have been made with other approaches like genome-wide CRISPR screenings, making the current study distinctive. Consequently, the study provides important messages. First, it shows that PUFAs are essential for life. The inability to genetically rescue PUFA deficiency, except for mutations that restore PUFA levels, suggests that they have pleiotropic essential functions. In addition, the results suggest that the most essential functions of PUFAs are not in fluidity regulation, which is consistent with recent reviews proposing that the importance of unsaturation goes beyond fluidity (doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2023.08.004 and doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a041409). Thus, the study provides fundamental insights about how membrane lipid composition can be linked to biological functions.

Weaknesses:

The authors put in a lot of effort to answer the questions that arose through peer review, and now all the claims seem to be supported by experimental data. Thus, I do not see obvious weaknesses. Of course, it remains unclear what PUFAs do beyond fluidity regulation, but this is something that cannot be answered from a single study.

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

Reviewer #1:

The addition of the discussion about the two isomers of 18:1 didn't quite work in the place that the authors added. What the authors wrote on line 126 is true about 18:1 isomers in wild type worms. However, they are reporting their lipidomics results of the fat-2(wa17) mutant worms. In this case, a substantial amount of the 18:1 is the oleic acid (18:1n-9) isomer. The authors can check Table 2 in their reference [10] and see that wild type and other fat mutants indeed contain approximately 10 fold more cis vaccenic than oleic acid, the fat-2(wa17) mutants do accumulate oleic acid, because the wild type activity of FAT-2 is to convert oleic acid to linoleic acid, where it can be converted to downstream PUFAs. I suggest editing their sentence …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

Reviewer #1:

The addition of the discussion about the two isomers of 18:1 didn't quite work in the place that the authors added. What the authors wrote on line 126 is true about 18:1 isomers in wild type worms. However, they are reporting their lipidomics results of the fat-2(wa17) mutant worms. In this case, a substantial amount of the 18:1 is the oleic acid (18:1n-9) isomer. The authors can check Table 2 in their reference [10] and see that wild type and other fat mutants indeed contain approximately 10 fold more cis vaccenic than oleic acid, the fat-2(wa17) mutants do accumulate oleic acid, because the wild type activity of FAT-2 is to convert oleic acid to linoleic acid, where it can be converted to downstream PUFAs. I suggest editing their sentence on line 126 to say that the high 18:1 they observed agrees with [10], and then comment about reference 10 showing the majority of 18:1 being the cis-vaccenic isomer in most strains, but the oleic acid isomer is more abundantly in the fat-2(wa17) mutant strain.

We thank the reviewer for spotting that and sparing us a bit of embarrassment. We have now modified the text and hope we got it right this time:

"Even though the lipid analysis methods used here are not able to distinguish between different 18:1 species, a previous study showed that the majority of the 18:1 fatty acids in the fat-2(wa17) mutant is actually 18:1n9 (OA) [10] and not 18:1n7 (vaccenic acid) as in most other strains [10,23]; this is because OA is the substrate of FAT-2 and thus accumulates in the mutant."

Reviewer #2:

I still do not agree with the answer to my previous comment 6 regarding Figure S2E. The authors claim that hif-1(et69) suppresses fat-2(wa17) in a ftn-2 null background (in Figure S2 legend for example). To claim so, they would need to compare the triple mutant with fat2(wa17);ftn-2(ok404) and show some rescue. However, we see in Figure 5H that ftn2(ok404) alone rescues fat-2(wa17). Thus, by comparing both figures, I see no additional effect of hif-1(et69) in an ftn-2(ok404) background. I actually think that this makes more sense, since the authors claim that hif-1(et69) is a gain-of-function mutation that acts through suppression of ftn-2 expression. Thus, I would expect that without ftn-2 from the beginning, hif-1(et69) does not have an additional effect, and this seems to be what we see from the data. Thus, I would suggest that the authors reformulate their claims regarding the effect of hif1(et69) in the ftn-2(ok404) background, which seems to be absent (consistently with what one would expect).

We completely agree with the reviewer and indeed this is the meaning that we tried to convey all along. The text has now been modified as follows:

"Lastly, ftn-2(et68) is still a potent fat-2(wa17) suppressor when hif-1 is knocked out (S2D Fig), suggesting that no other HIF-1-dependent functions are required as long as ftn-2 is downregulated; this conclusion is supported by the observation that the potency of the ftn2(ok404) null allele to act as a fat-2(wa17) suppressor is not increased by including the hif-1(et69) allele (compare Fig 5H and S2E Fig)."

-

-

eLife Assessment

This fundamental study investigates the role of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in physiology and membrane biology, using a unique model to perform a thorough genetic screen that demonstrates that PUFA synthesis defects cannot be compensated for by mutations in other pathways. These findings are supported by compelling evidence from a high quality genetic screen, functional validation of their hits, and lipid analyses. This study will appeal to researchers in membrane biology, lipid metabolism, and C. elegans genetics.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

This study addresses the roles of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in animal physiology and membrane function. A C. elegans strain carrying the fat-2(wa17) mutation possess a very limited ability to synthesize PUFAs and there is no dietary input because the E. coli diet consumed by lab grown C. elegans does not contain any PUFAs. The fat-2 mutant strain was characterized to confirm that the worms grow slowly, have rigid membranes, and have a constitutive mitochondrial stress response. The authors showed that chemical treatments or mutations known to increase membrane fluidity did not rescue growth defects. A thorough genetic screen was performed to identify genetic changes to compensate for the lack of PUFAs. The newly isolated suppressor mutations that compensated for FAT-2 growth defects …

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

This study addresses the roles of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in animal physiology and membrane function. A C. elegans strain carrying the fat-2(wa17) mutation possess a very limited ability to synthesize PUFAs and there is no dietary input because the E. coli diet consumed by lab grown C. elegans does not contain any PUFAs. The fat-2 mutant strain was characterized to confirm that the worms grow slowly, have rigid membranes, and have a constitutive mitochondrial stress response. The authors showed that chemical treatments or mutations known to increase membrane fluidity did not rescue growth defects. A thorough genetic screen was performed to identify genetic changes to compensate for the lack of PUFAs. The newly isolated suppressor mutations that compensated for FAT-2 growth defects included intergenic suppressors in the fat-2 gene, as well as constitutive mutations in the hypoxia sensing pathway components EGL-9 and HIF-1, and loss of function mutations in ftn-2, a gene encoding the iron storage protein ferritin. Taken together, these mutations lead to the model that increased intracellular iron, an essential cofactor for fatty acid desaturases, allows the minimally functional FAT-2(wa17) enzyme to be more active, resulting in increased desaturation and increased PUFA synthesis.

Strengths:

(1) This study provides new information further characterizing fat-2 mutants. The authors measured increased rigidity of membranes compared to wild type worms, however this rigidity is not able to be rescued with other fluidity treatments such as detergent or mutants. Rescue was only achieved with polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation.

(2) A very thorough genetic suppressor screen was performed. In addition to some internal fat-2 compensatory mutations, the only changes in pathways identified that are capable of compensating for deficient PUFA synthesis was the hypoxia pathway and the iron storage protein ferritin. Suppressor mutations included an egl-9 mutation that constitutively activates HIF-1, and Gain of function mutations in hif-1 that are dominant. This increased activity of HIF conferred by specific egl-9 and hif-1 mutations lead to decreased expression of ftn-2. Indeed, loss of ftn-2 leads to higher intracellular iron. The increased iron apparently makes the FAT-2 fatty acid desaturase enzyme more active, allowing for the production of more PUFAs.

(3) The mutations isolated in the suppressor screen show that the only mutations able to compensate for lack of PUFAs were ones that increased PUFA synthesis by the defective FAT-2 desaturase, thus demonstrating the essential need for PUFAs that cannot be overcome by changes in other pathways. This is a very novel study, taking advantage of genetic analysis of C. elegans, and it confirms the observations in humans that certain essential PUFAs are required for growth and development.

(4) Overall, the paper is well written, and the experiments were carried out carefully and thoroughly. The conclusions are well supported by the results.Weaknesses:

Overall, there are not many weaknesses. The main one I noticed is that the lipidomic analysis shown in Figs 3C, 7C, S1 and S3. Whie these data are an essential part of the analysis and provide strong evidence for the conclusions of the study, it is unfortunate that the methods used did not enable the distinction between two 18:1 isomers. These two isomers of 18:1 are important in C. elegans biology, because one is a substrate for FAT-2 (18:1n-9, oleic acid) and the other is not (18:1n-7, cis vaccenic acid). Although rarer in mammals, cis-vaccenic acid is the most abundant fatty acid in C. elegans and is likely the most important structural MUFA. The measurement of these two isomers is not essential for the conclusions of the study, but the manuscript should include a comment about the abundance of oleic vs vaccenic acid in C. elegans (authors can find this information, even in the fat-2 mutant, in other publications of C. elegans fatty acid composition). Otherwise, readers who are not familiar with C. elegans might assume the 18:1 that is reported is likely to be mainly oleic acid, as is common in mammals.

Other suggestions to authors to improve the paper:

(1) The title could be less specific; it might be confusing to readers to include the allele name in the title.

(2) There are two errors in the pathway depicted in Figure 1A. The16:0-16:1 desaturation can be performed by FAT-5, FAT-6, and FAT-7. The 18:0-18:1 desaturation can only be performed by FAT-6 and FAT-7 -

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors use a genetic screen in C. elegans to investigate the physiological roles of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). They screen for mutations that rescue fat-2 mutants, which have strong reductions in PUFAs. As a result, either mutations in fat-2 itself, or mutations in genes involved in the HIF-1 pathway, were found to rescue fat-2 mutants. Mutants in the HIF-1 pathway rescue fat-2 mutants by boosting its catalytic activity (via upregulated Fe2+). Thus, the authors show that in the context of fat-2 mutation, the sole genetic means to rescue PUFA insufficiency is to restore PUFA levels.

Strengths:

As C. elegans can produce PUFAs de novo as essential lipids, the genetic model is well suited to study the fundamental roles of PUFAs. The genetic screen finds mutations in convergent pathways, …

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors use a genetic screen in C. elegans to investigate the physiological roles of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). They screen for mutations that rescue fat-2 mutants, which have strong reductions in PUFAs. As a result, either mutations in fat-2 itself, or mutations in genes involved in the HIF-1 pathway, were found to rescue fat-2 mutants. Mutants in the HIF-1 pathway rescue fat-2 mutants by boosting its catalytic activity (via upregulated Fe2+). Thus, the authors show that in the context of fat-2 mutation, the sole genetic means to rescue PUFA insufficiency is to restore PUFA levels.

Strengths:

As C. elegans can produce PUFAs de novo as essential lipids, the genetic model is well suited to study the fundamental roles of PUFAs. The genetic screen finds mutations in convergent pathways, suggesting that it has reached near-saturation. The authors extensively validate the results of the screening and provide sufficient mechanistic insights to show how PUFA levels are restored in HIF-1 pathway mutants. As many of the mutations found to rescue fat-2 mutants are of gain-of-function, it is unlikely that similar discoveries could have been made with other approaches like genome-wide CRISPR screenings, making the current study distinctive. Consequently, the study provides important messages. First, it shows that PUFAs are essential for life. The inability to genetically rescue PUFA deficiency, except for mutations that restore PUFA levels, suggests that they have pleiotropic essential functions. In addition, the results suggest that the most essential functions of PUFAs are not in fluidity regulation, which is consistent with recent reviews proposing that the importance of unsaturation goes beyond fluidity (doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2023.08.004 and doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a041409). Thus, the study provides fundamental insights about how membrane lipid composition can be linked to biological functions.

Weaknesses:

The authors did a lot of efforts to answer the questions that arose through peer review, and now all the claims seem to be supported by experimental data. Thus, I do not see obvious weaknesses. Of course, it remains still unclear what PUFAs do beyond fluidity regulation, but this is something that cannot be answered from a single study. I just have one final proposition to make.

I still do not agree with the answer to my previous comment 6 regarding Figure S2E. The authors claim that hif-1(et69) suppresses fat-2(wa17) in a ftn-2 null background (in Figure S2 legend for example). To claim so, they would need to compare the triple mutant with fat-2(wa17);ftn-2(ok404) and show some rescue. However, we see in Figure 5H that ftn-2(ok404) alone rescues fat-2(wa17). Thus, by comparing both figures, I see no additional effect of hif-1(et69) in an ftn-2(ok404) background. I actually think that this makes more sense, since the authors claim that hif-1(et69) is a gain-of-function mutation that acts through suppression of ftn-2 expression. Thus, I would expect that without ftn-2 from the beginning, hif-1(et69) does not have an additional effect, and this seems to be what we see from the data. Thus, I would suggest that the authors reformulate their claims regarding the effect of hif-1(et69) in the ftn-2(ok404) background, which seems to be absent (consistently with what one would expect).

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews

Reviewer #1:

While very positive towards our manuscript, this reviewer also points out three suggestions for improvement.

Overall, there are not many weaknesses. The main one I noticed is with the lipidomic analysis shown in Figs 3C, 7C, S1 and S3. While these data are an essential part of the analysis and provide strong evidence for the conclusions of the study, it is unfortunate that the methods used did not enable the distinction between two 18:1 isomers. These two isomers of 18:1 are important in C. elegans biology, because one is a substrate for FAT-2 (18:1n-9, oleic acid) and the other is not (18:1n-7, cis vaccenic acid). Although rarer in mammals, cisvaccenic acid is the most abundant fatty acid in C. elegans and is likely the most important …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews

Reviewer #1:

While very positive towards our manuscript, this reviewer also points out three suggestions for improvement.

Overall, there are not many weaknesses. The main one I noticed is with the lipidomic analysis shown in Figs 3C, 7C, S1 and S3. While these data are an essential part of the analysis and provide strong evidence for the conclusions of the study, it is unfortunate that the methods used did not enable the distinction between two 18:1 isomers. These two isomers of 18:1 are important in C. elegans biology, because one is a substrate for FAT-2 (18:1n-9, oleic acid) and the other is not (18:1n-7, cis vaccenic acid). Although rarer in mammals, cisvaccenic acid is the most abundant fatty acid in C. elegans and is likely the most important structural MUFA. The measurement of these two isomers is not essential for the conclusions of the study, but the manuscript should include a comment about the abundance of oleic vs vaccenic acid in C. elegans (authors can find this information, even in the fat-2 mutant, in other publications of C. elegans fatty acid composition). Otherwise, readers who are not familiar with C. elegans might assume the 18:1 that is reported is likely to be mainly oleic acid, as is common in mammals.

Excellent point. As suggested by the reviewer, we now include a clarification of this in the text: "Consistent with previous publications [10], the levels of 18:1 fatty acids were greatly increased in the fat-2(wa17) mutant. It is important to note that the majority of these 18:1 fatty acids is likely 18:1n7 (vaccenic acid) and not 18:1n9 (OA) [10,23], which is the substrate of FAT-2; the lipid analysis methods used here are not able to distinguish between the two 18:1 species."

The title could be less specific; it might be confusing to readers to include the allele name in the title.

We thank the reviewer for the suggestion, and we have now modified the title:

"Forward Genetics In C. elegans Reveals Genetic Adaptations To Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Deficiency"

There are two errors in the pathway depicted in Figure 1A. The16:0-16:1 desaturation can be performed by FAT-5, FAT-6, and FAT-7. The 18:0-18:1 desaturation can only be performed by FAT-6 and FAT-7.

We thank the reviewer for pointing out this mistake. The pathway in Fig. 1A has been corrected.

Reviewer #2:

This reviewer was also very positive towards our manuscript but also pointed out several suggestions for additional experiments or changes to the manuscript.

Major recommendations

(1) To conclude that membrane rigidification is not the major cause of defects associated with fat-2 mutations, the authors need to show that fluidity is rescued by their treatments (oleic acid or NP-40). I honestly doubt that it is the case, as oleic acid is already abundant in fat-2 mutants. It is possible that the treatments, which are effective in rescuing fluidity in paqr-2 mutants, do not have the same effects in fat-2 mutants.

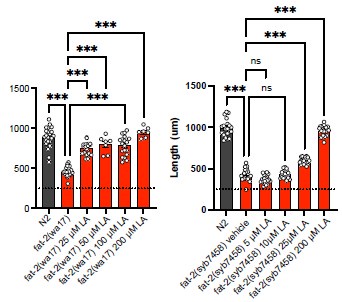

The reviewer raises an important point. In an effort to address this, we have now performed a FRAP study on fat-2(wa17) mutants with/without NP40 as a fluidizing agent (with wild-type and paqr-2 mutants as controls). The new data, now included as Fig. 2J, shows that NP40 did improve the fluidity of the intestinal cell membrane in the fat-2(wa17) mutant, though not to the same degree as in the paqr-2 mutant. This is now cited in the text as follows:

"However, cultivating the fat-2(wa17) mutant in the presence of the non-ionic detergent NP40, which improves the growth of the paqr-2(tm3410) mutant [17], did not suppress the poor growth phenotype of the fat-2(wa17) mutant even though it did improve membrane fluidity as measured using FRAP (Fig. 2I-J). Similarly, supplementing the fat-2(wa17) mutant with the MUFA oleic acid (OA, 18:1), which also suppresses paqr-2(tm3410) phenotypes [17], did not suppress the poor growth phenotype of the fat-2(wa17) mutant (Fig 2K)."

(2) It is not validated experimentally that the mutations converge into FTN-2 repression. This can be verified by analyzing mRNA or protein expression of FTN-2 in the egl-9 and hif-1 mutants obtained in the screening.

Our manuscript does lean on several publications that previously established the HIF-1 pathway in C. elegans. Additionally, we now added a qPCR experiment showing that the newly isolated hif-1(et69) allele indeed suppresses the expression of ftn-2. This was an especially valuable experiment since the hif-1(et69) is proposed to act as a gain-of-function allele that would constitutively suppress ftn-2 expression. This new result is included as Fig. 6C and mentioned in the text:

"Inhibition of egl-9 promotes HIF-1 activity [41], which we here verified for the egl-9(et60) allele using western blots (Fig 6A). Additionally, we found by qPCR that ftn-2 mRNA levels are as expected reduced by the proposed gain-of-function hif-1(et69) allele (Fig 6C). We conclude that the egl-9 and hif-1 suppressor mutations likely converge on inhibiting ftn-2 and thus act similarly to the ftn-2 loss-of-function alleles."

(3) In the hif-1(et69) and ftn-2(et68) mutants, the rescues in lipid composition seem to be minor, with eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) levels remaining low. The ftn-2 mutant data is especially concerning, as it suggests that egl-9 mutants rescue lipid composition via distinct mechanisms not including ftn-2 suppression. I suggest that the authors test the minimal doses of linoleic acid or EPA required to rescue fat-2 mutants and perform lipidomics to test which is the degree of EPA restoration that is needed. If a low level of restoration is sufficient, the hif-1 and ftn-2 mutants might indeed rescue phenotypes via a restoration of EPA levels. Otherwise, other mechanisms have to be considered.

In line with the above issue, the low level or EPA restoration in hif-1 and ftn-2 mutants raise the possibility that the mutations rescue fat-2 mutants downstream of lipid changes. The reduction in HIF-1 levels in fat-2 mutants also suggest that lipid changes affect HIF-1 expression. Thus, the "impossibility to genetically compensate PUFA deficiency" might be wrong. The above experiment would answer to this point too.

The reviewer is entirely correct to consider alternative explanations. In the lipidomics in Fig 3, we see that fat-2(wa17) worms on NGM have only ~1.5-2%mol EPA in phosphatidylcholines. When treated with 2 mM LA, the levels of EPA rise to ~10%mol, still below the ~ 25% observed in N2 but perhaps this is sufficient cause for restoring fat-2(wa17) health. Similarly, the hif-1(et69) and ftn-2(et68) mutant alleles elevate EPA levels to 5- 7% in fat-2(wa17). Thus, we have a correlation where a significant increase in EPA, obtained either through LA supplementation or through suppressor mutations (e.g. egl-9 (et60), hif-1(et69) or ftn-2(et68)), is associated with improved growth and health of the fat-2(wa17) mutant. However, correlation is of course not proof. The suggested experiment to titrate EPA to its lowest fat-2(wa17) rescuing levels and then perform lipidomics analysis was not possible in a reasonable time frame during this revision. However, preliminary experiments showed that even 25 μM LA (most of which will be converted to EPA by the worms) is enough to rescue the fat-2(wa17) or null mutant (Author response image 1), suggesting that even tiny amounts (much below the >250 μM used in our article) bring great benefits.

Author response image 1.

Nevertheless, we now acknowledge in the discussion that alternative explanations exist:

"Other mechanisms are also possible. For example, mutations in the HIF-1 pathway could somehow reduce EPA turnover rates in the fat-2(wa17) mutant and allow its levels to rise above an essential threshold. This hypothesis is consistent with the observation that the suppressors can rescue both the fat-2(wa17) mutant and fat-2 RNAi-treated worms but not the fat-2 null mutant. It is even possible, though deemed unlikely, that the fat-2(wa17) suppressors act by compensating for the PUFA shortage via some undefined separate process downstream of the lipid changes and that they only indirectly result in elevated EPA levels."

Additionally, another possible mechanism of action of the fat-2(wa17) suppressors could have been that they all cause upregulation of the FAT-2 protein. We have now explored this possibility using Western blots and found that this is an unlikely mechanism. This is presented in Fig. 6D-E and S3C-D, mentioned in the text as follows:

"We also used Western blots to evaluate the abundance of the FAT-2 protein expressed from endogenous wild-type or mutant loci but to which a HA tag was fused using CRISPR/Cas9. We found that the FAT-2::HA levels are severely reduced when the locus contains the S101F substitution present in the wa17 allele, but restored close to wild-type levels by the fat2(et65) suppressor mutation (Fig 6D-E, S3C-D Fig). The levels of FAT-2 in the HIF-1 pathway suppressors varied between experiments, with the suppressors sometimes restoring FAT-2 levels and sometimes not even when the worms were growing well (Fig 6D-E, S3C-D Fig). The fat-2(wa17) suppressors, except for the intragenic fat-2 alleles, likely do not act by increasing FAT-2 protein levels."

(4) It should be tested how Fe2+ levels are changed in the mutants, and how effective the ferric ammonium citrate treatment is. The authors might use a ftn-1::GFP reporter for this purpose.

We did obtain a strain carrying the ftn-1::GFP reporter but could not generate conclusive data with it. In particular, we saw no increase in fluorescence in fat-2(wa17) worms carrying suppressor mutations. However, we also found that even FAC treatment that rescue the fat2(wa17) mutant did not result in a measurable increased GFP levels suggesting that the reporter is not sensitive enough.

Minor comments

(1) I think that putting Figure 6A in Figure 5 would be helpful for the readers, so that they understand that the mutations converge in the same pathway.

This is now done.

(2) Page 3: While it is clear that paqr-2 regulates lipid composition, I believe that it remains unclear if it "promote the production and incorporation of PUFAs into phospholipids to restore membrane homeostasis".

A reference was missing to support that statement. Ruiz et al. (2023) is now cited for this (ref. 7).

(3) C. elegans is extremely rich in EPA (see for example DOI: 10.3390/jcm5020019), but the lipidomics data in this study rather suggest that oleic acid is predominant. I recommend to check why this discrepancy occurs.

OA (18:1n9) makes up only ~2%, but vaccenic acid (18:1n7) is ~21% in WT worms, EPA is slightly less at ~19% (Watts et al. 2002). These match with our lipidomics results although we cannot distinguish between 18:1n9 and n7. See also answer to Reviewer #1, comment 1.

(4) Abstract: The authors write that mammals do not synthesize PUFAs, which is almost correct, but they still produce the PUFA mead acid. Thus, the statement is not completely right.

Didn't know that! From literature, it is our understanding that mammals synthesize mead acid during FA deficiency but not in normal conditions, so they are not regularly producing mead acid. We have now updated the introduction:

"An exception to this exists during severe essential fatty acid deficiency when mammals can synthesize mead acid (20:3n9), though this is not a common occurrence [11]"

(5) Page 10: Eicosanoids are C20 lipid mediators, thus those produced from docosahexaenoic acid are not eicosanoids. Correct the statement.

We thank the reviewer for pointing this out. We now write:

" EPA and DHA, being long chain PUFAs should have similar fluidizing effects on membrane properties (though in vitro experiments challenge this view [78]), and both can serve as precursors of eicosanoids or docosanoids, particularly inflammatory ones [79]."

(6) Page 7: "hif-1(et69) is similarly able to suppress fat-2(wa17) when ftn-2 is knocked out" I am not sure that the data agrees with this statement, and it is unclear what we can conclude from such observation.

Fig. 2D shows that ftn-2(et68) suppresses fat-2(wa17) even in the presence of a hif-1(ok2654) null allele, showing that no HIF-1 function is required once ftn-2 is mutated. Conversely, Fig S2E shows that combining both the hif-1(et69) and the ftn-2(ok404) null allele also suppresses fat-2(wa17) (the worms do not fully reach N2 length, but they are significantly longer and were fertile adults); this is merely the expected outcome if the pathway converges on loss of ftn-2 function, though other interpretations could be possible from this experiment alone.

(7) S3 Fig: in panel B, is the last column ftn-2;egl-9 mutant? I would imagine that it is ftn2;fat-2.

We thank the reviewer for pointing this out. This has been corrected.

(8) Fig 6B, how many times has been this experiment done?

With these exact conditions (6h and 20h hypoxia) and order of strains the blot was done once, but the blot overall was done 5 times. We now added another replicate in Fig. S3A.

Note also that a few minor modifications have been made throughout the text, which can be seen in the Word file with tracked changes.

-

-

eLife Assessment

This study investigates the fundamental role of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in membrane biology, using a unique model to perform a thorough genetic screen that highlights that PUFA synthesis defects cannot be compensated for by mutations in other pathways. While the data are solid and generally support the claims, additional experimental validation or more detailed descriptions of their results would strengthen the broader conclusions. This study will appeal to researchers in membrane biology, lipid metabolism, and C. elegans genetics.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

This study addresses the roles of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in animal physiology and membrane function. A C. elegans strain carrying the fat-2(wa17) mutation possess a very limited ability to synthesize PUFAs and there is no dietary input because the E. coli diet consumed by lab grown C. elegans does not contain any PUFAs. The fat-2 mutant strain was characterized to confirm that the worms grow slowly, have rigid membranes, and have a constitutive mitochondrial stress response. The authors showed that chemical treatments or mutations known to increase membrane fluidity did not rescue growth defects. A thorough genetic screen was performed to identify genetic changes to compensate for the lack of PUFAs. The newly isolated suppressor mutations that compensated for FAT-2 growth defects …Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

This study addresses the roles of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in animal physiology and membrane function. A C. elegans strain carrying the fat-2(wa17) mutation possess a very limited ability to synthesize PUFAs and there is no dietary input because the E. coli diet consumed by lab grown C. elegans does not contain any PUFAs. The fat-2 mutant strain was characterized to confirm that the worms grow slowly, have rigid membranes, and have a constitutive mitochondrial stress response. The authors showed that chemical treatments or mutations known to increase membrane fluidity did not rescue growth defects. A thorough genetic screen was performed to identify genetic changes to compensate for the lack of PUFAs. The newly isolated suppressor mutations that compensated for FAT-2 growth defects included intergenic suppressors in the fat-2 gene, as well as constitutive mutations in the hypoxia sensing pathway components EGL-9 and HIF-1, and loss of function mutations in ftn-2, a gene encoding the iron storage protein ferritin. Taken together, these mutations lead to the model that increased intracellular iron, an essential cofactor for fatty acid desaturases, allows the minimally functional FAT-2(wa17) enzyme to be more active, resulting in increased desaturation and increased PUFA synthesis.Strengths:

(1) This study provides new information further characterizing fat-2 mutants. The authors measured increased rigidity of membranes compared to wild type worms, however this rigidity is not able to be rescued with other fluidity treatments such as detergent or mutants. Rescue was only achieved with polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation.

(2) A very thorough genetic suppressor screen was performed. In addition to some internal fat-2 compensatory mutations, the only changes in pathways identified that are capable of compensating for deficient PUFA synthesis was the hypoxia pathway and the iron storage protein ferritin. Suppressor mutations included an egl-9 mutation that constitutively activates HIF-1, and Gain of function mutations in hif-1 that are dominant. This increased activity of HIF conferred by specific egl-9 and hif-1 mutations lead to decreased expression of ftn-2. Indeed, loss of ftn-2 leads to higher intracellular iron. The increased iron apparently makes the FAT-2 fatty acid desaturase enzyme more active, allowing for the production of more PUFAs.

(3) The mutations isolated in the suppressor screen show that the only mutations able to compensate for lack of PUFAs were ones that increased PUFA synthesis by the defective FAT-2 desaturase, thus demonstrating the essential need for PUFAs that cannot be overcome by changes in other pathways. This is a very novel study, taking advantage of genetic analysis of C. elegans, and it confirms the observations in humans that certain essential PUFAs are required for growth and development.

(4) Overall, the paper is well written, and the experiments were carried out carefully and thoroughly. The conclusions are well supported by the results.Weaknesses:

Overall, there are not many weaknesses. The main one I noticed is that the lipidomic analysis shown in Figs 3C, 7C, S1 and S3. Whie these data are an essential part of the analysis and provide strong evidence for the conclusions of the study, it is unfortunate that the methods used did not enable the distinction between two 18:1 isomers. These two isomers of 18:1 are important in C. elegans biology, because one is a substrate for FAT-2 (18:1n-9, oleic acid) and the other is not (18:1n-7, cis vaccenic acid). Although rarer in mammals, cis-vaccenic acid is the most abundant fatty acid in C. elegans and is likely the most important structural MUFA. The measurement of these two isomers is not essential for the conclusions of the study, but the manuscript should include a comment about the abundance of oleic vs vaccenic acid in C. elegans (authors can find this information, even in the fat-2 mutant, in other publications of C. elegans fatty acid composition). Otherwise, readers who are not familiar with C. elegans might assume the 18:1 that is reported is likely to be mainly oleic acid, as is common in mammals.Other suggestions to authors to improve the paper:

(1) The title could be less specific; it might be confusing to readers to include the allele name in the title.

(2) There are two errors in the pathway depicted in Figure 1A. The16:0-16:1 desaturation can be performed by FAT-5, FAT-6, and FAT-7. The 18:0-18:1 desaturation can only be performed by FAT-6 and FAT-7 -

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors use a genetic screen in C. elegans to investigate the physiological roles of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). They screen for mutations that rescue fat-2 mutants, which have strong reductions in PUFAs. As a result, either mutations in fat-2 itself, or mutations in genes involved in the HIF-1 pathway, were found to rescue fat-2 mutants.Strengths:

As C. elegans can produce PUFAs de novo as essential lipids, the genetic model is well suited to study the fundamental roles of PUFAs, and the results are very interesting. The genetic screen finds mutations in convergent pathways, suggesting that it has reached near-saturation. The link between the HIF-1 pathway and lipid unsaturation is very interesting. As many of the mutations found to rescue fat-2 mutants are of gain-of-function, it is …Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors use a genetic screen in C. elegans to investigate the physiological roles of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). They screen for mutations that rescue fat-2 mutants, which have strong reductions in PUFAs. As a result, either mutations in fat-2 itself, or mutations in genes involved in the HIF-1 pathway, were found to rescue fat-2 mutants.Strengths:

As C. elegans can produce PUFAs de novo as essential lipids, the genetic model is well suited to study the fundamental roles of PUFAs, and the results are very interesting. The genetic screen finds mutations in convergent pathways, suggesting that it has reached near-saturation. The link between the HIF-1 pathway and lipid unsaturation is very interesting. As many of the mutations found to rescue fat-2 mutants are of gain-of-function, it is unlikely that similar discoveries could have been made with other approaches like genome-wide CRISPR screenings, making the current study distinctive.Weaknesses:

The authors make very important statements, but some are not sufficiently supported by data. In page 5, they conclude that membrane rigidity is a minor cause of fat-2 mutant defects, which is a relevant observation regarding why PUFAs are important. However, they use treatments that have rescued fluidity in another mutant (paqr-2), but do not test if they have the same fluidifying effects in fat-2 mutants.The screening results seem to converge into the HIF-1 pathway, which is hypothetically correct according to the literature. However, the authors do not validate this hypothesis, which is a critical limitation, especially because many of the mutations they obtained seem to be of gain-of-function. Therefore, without experimental testing, it cannot be concluded that the mutations have the expected effect on the HIF-1 pathway.

In some of the mutants, the rescues in lipid compositions seem to be weak, and it is arguable whether phenotypic rescues are really via a restoration in lipid compositions.

The hypothesis linking iron homeostasis and the rescue of fat-2 mutants is interesting, but the data of rescue by iron repletion seem to be against it. The results might be due to the inefficiency in iron repletion, as the authors suggest, but this has not been formally addressed.

Therefore, the authors propose multiple very interesting and important hypotheses, but experimental validations remain limited.

-

Author response:

We thank the editors at eLife and the reviewers for the care with which our mansucript has been reviewed and the constructive feedback that we have received. Both reviewers viewed the manuscript positively and in particular praised the merits of the forward genetic screen that led to the discovery of a new link between the HIF-1 pathway and fatty acid desaturation.

We agree with all points by Reviewer #1. We will modify our manuscript to clarify that two types of C18:1 fatty acids are present in our lipidomics, and that the majority is likely vaccenic acid that is not a FAT-2 substrate. The title will be modified and Fig. 1A corrected.

All points raised by Reviewer #2 are also valid and we will try to address most of them experimentally, though not always as suggested. In particular, we plan to use FRAP to verify that …

Author response:

We thank the editors at eLife and the reviewers for the care with which our mansucript has been reviewed and the constructive feedback that we have received. Both reviewers viewed the manuscript positively and in particular praised the merits of the forward genetic screen that led to the discovery of a new link between the HIF-1 pathway and fatty acid desaturation.

We agree with all points by Reviewer #1. We will modify our manuscript to clarify that two types of C18:1 fatty acids are present in our lipidomics, and that the majority is likely vaccenic acid that is not a FAT-2 substrate. The title will be modified and Fig. 1A corrected.

All points raised by Reviewer #2 are also valid and we will try to address most of them experimentally, though not always as suggested. In particular, we plan to use FRAP to verify that membrane-fluidizing treatments are effective in the fat-2 mutant. We also plan to use qPCR to test whether the novel egl-9(lof) and hif-1(gof) alleles lead to the expected downregulation of ftn-2. We note that the pathway connecting EGL-9, HIF-1 and FTN-2 is well supported by published work and that the alleles isolated in our screen are consistent with it, with the addition that FAT-2 is likely a regulated outcome of FTN-2 inhibition/mutation. We also plan to monitor FAT-2 protein levels using Western blots and thus provide more clarity about the mechanism of action of the novel fat-2(wa17) suppressors. The manuscript will be modified to tone down interpretations not directly supported by experiments.

-

-