Enhanced bacterial chemotaxis in confined microchannels: Optimal performance in lane widths matching circular swimming radius

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

eLife Assessment

This important work examines the effects of side-wall confinement on chemotaxis of swimming bacteria in a shallow microfluidic channel. The authors present convincing experimental evidence, combined with geometric analysis and numerical simulations of simplified models, showing that chemotaxis is enhanced when the distance between the side walls is comparable to the intrinsic radius of chiral circular swimming near open surfaces. This study should be of interest to scientists specializing in bacteria-surface interactions.

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

Understanding bacterial behavior in confined environments is helpful for elucidating microbial ecology and developing strategies to manage bacterial infections. While extensive research has focused on bacterial motility on surfaces and in porous media, chemotaxis in confined spaces remains poorly understood. Here, we investigate the chemotaxis of Escherichia coli within microfluidic lanes under a linear concentration gradient of L-aspartate. We demonstrate that E. coli exhibits significantly enhanced chemotaxis in lanes with sidewalls compared to open surfaces. We attribute this phenomenon primarily to the intrinsic clockwise circular motion of surface-swimming bacteria and the subsequent alignment effect upon collision with the sidewalls. By varying lane widths, we identify that an 8 μm width—approximating the radius of bacterial circular swimming on surfaces—maximizes chemotactic drift velocity. These results are supported by both experimental observations and stochastic simulations, establishing a clear proportional relationship between optimal lane width and the radius of bacterial circular swimming. Further geometric analysis provides an intuitive understanding of this phenomenon. Our results may offer insights into bacterial navigation in complex biological environments such as host tissues and biofilms, providing a preliminary step toward exploring microbial ecology in confined habitats and potential strategies for controlling bacterial infections.

Article activity feed

-

eLife Assessment

This important work examines the effects of side-wall confinement on chemotaxis of swimming bacteria in a shallow microfluidic channel. The authors present convincing experimental evidence, combined with geometric analysis and numerical simulations of simplified models, showing that chemotaxis is enhanced when the distance between the side walls is comparable to the intrinsic radius of chiral circular swimming near open surfaces. This study should be of interest to scientists specializing in bacteria-surface interactions.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

The authors show experimentally that, in 2D, bacteria swim up a chemotactic gradient much more effectively when they are in the presence of lateral walls. Systematic experiments identify an optimum for chemotaxis for a channel width of ~8µm, a value close to the average radius of the circle trajectories of the unconfined bacteria in 2D. These chiral circles impose that the bacteria swim preferentially along the right-side wall, which indeed yields chemotaxis in the presence of a chemotactic gradient. These observations are backed by numerical simulations and a geometrical analysis.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

This paper addresses, through experiment and simulation, the combined effects of bacterial circular swimming near no-slip surfaces and chemotaxis in simple linear gradients. The authors have constructed a microfluidic device in which a gradient of L-aspartate is established, to which bacteria respond while swimming while confined in channels of different widths. There is a clear effect that the chemotactic drift velocity reaches a maximum in channel widths of about 8 microns, similar in size to the circular orbits that would prevail in the absence of side walls. Numerical studies of simplified models confirm this connection.

The experimental aspects of this study are well executed. The design of the microfluidic system is clever in that it allows a kind of "multiplexing" in which all the different channel …

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

This paper addresses, through experiment and simulation, the combined effects of bacterial circular swimming near no-slip surfaces and chemotaxis in simple linear gradients. The authors have constructed a microfluidic device in which a gradient of L-aspartate is established, to which bacteria respond while swimming while confined in channels of different widths. There is a clear effect that the chemotactic drift velocity reaches a maximum in channel widths of about 8 microns, similar in size to the circular orbits that would prevail in the absence of side walls. Numerical studies of simplified models confirm this connection.

The experimental aspects of this study are well executed. The design of the microfluidic system is clever in that it allows a kind of "multiplexing" in which all the different channel widths are available to a given sample of bacteria.

The authors have included a useful intuitive explanation of their results via a geometric model of the trajectories. In future work it would be interesting to analyze further the voluminous data on the trajectories of cells by formulating the mathematical problem in terms of a suitable Fokker-Planck equation for the probability distribution of swimming directions. In particular, this might help understand how incipient circular trajectories are interrupted by collisions with the walls and how this relates to enhanced chemotaxis.The authors argue that these findings may have relevance to a number of physiological and ecological contexts. As these would be characterized by significant heterogeneity in pore sizes and geometries, further work will be necessary to translate the present results to those situations.

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

This article deals with the chemotactic behavior of E coli bacteria in thin channels (a situation close to 2D). It combines experiments and simulations.

The authors show experimentally that, in 2D, bacteria swim up a chemotactic gradient much more effectively when they are in the presence of lateral walls. Systematic experiments identify an optimum for chemotaxis for a channel width of ~8µm, close to the average radius of the circle trajectories of the unconfined bacteria in 2D. It is known that these circles are chiral and impose that the bacteria swim preferentially along the right-side wall when there is no chemotactic gradient. In the presence of a chemotactic gradient, this larger proportion of bacteria …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

This article deals with the chemotactic behavior of E coli bacteria in thin channels (a situation close to 2D). It combines experiments and simulations.

The authors show experimentally that, in 2D, bacteria swim up a chemotactic gradient much more effectively when they are in the presence of lateral walls. Systematic experiments identify an optimum for chemotaxis for a channel width of ~8µm, close to the average radius of the circle trajectories of the unconfined bacteria in 2D. It is known that these circles are chiral and impose that the bacteria swim preferentially along the right-side wall when there is no chemotactic gradient. In the presence of a chemotactic gradient, this larger proportion of bacteria swimming on the right wall yields chemotaxis. This effect is backed by numerical simulations and a geometrical analysis.

If the conclusions drawn from the experiments presented in this article seem clear and interesting, I find that the key elements of the mechanism of this wall-directed chemotaxis are not sufficiently emphasized. Moreover, the paper would be clearer with more details on the hypotheses and the essential ingredients of the analyses.

We thank the reviewer for these constructive suggestions. We agree that emphasizing the underlying mechanism is crucial for the clarity of our findings. In the revised manuscript, we have now explicitly highlighted the critical roles of chiral circular motion and the alignment effect following side-wall collisions in both the Abstract (lines 25-27) and the Discussion (lines 391-393). Furthermore, we have added a new analysis of bacterial trajectories post-collision (Fig. S2), which demonstrates that cells predominantly align with and swim along the sidewalls. We have also clarified the assumptions in our numerical simulations, specifically how the radius of circular trajectories and the alignment effect are incorporated into the equations of motion. Please refer to our detailed responses in the "Recommendations for the authors" section for further specifics.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

In this study, the authors investigated the chemotaxis of E. coli swimming close to the bottom surface in gradients of attractant in channels of increasingly smaller width but fixed height = 30 µm and length ~160 µm. In relatively large channels, they find that on average the cells drift in response to the gradient, despite cells close to the surface away from the walls being known to not be chemotactic because they swim in circles.

They find that this average drift is due to the cell localization close to the side walls, where they slide along the wall. Whereas the bacteria away from the walls have no chemotaxis (as shown before), the ones on the left side wall go down-gradient on average, but the ones on the right-side wall go up-gradient faster, hence the average drift. They then study the effect of reducing channel width. They find that chemotaxis is higher in channels with a width of about 8 µm, which approximately corresponds to the radius of the circular swimming R. This higher chemotactic drift is concomitant to an increased density of cells on the RSW. They do simulations and modeling to suggest that the disruption of circular swimming upon collision with the wall increases the density of cells on the RSW, with a maximal effect at w = ~ 2/3 R, which is a good match for their experiments.

Strengths:

The overall result that confinement at the edge stabilises bacterial motion and allows chemotaxis is very interesting although not entirely unexpected. It is also important for understanding bacterial motility and chemotaxis under ecologically relevant conditions, where bacteria frequently swim under confinement (although its relevance for controlling infections could be questioned). The experimental part of the study is nicely supported by the model.

Weaknesses:

Several points of this study, in particular the interpretation of the width effect, need better clarification:

(1) Context:

There are a number of highly relevant previous publications that should have been acknowledged and discussed in relation to the current work:

https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2023/sm/d3sm00286a

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1140/epje/s10189-024-00450-7

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2022.04.008

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1816315116

https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.0907542106

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15711-0

We appreciate the reviewer bringing these important publications to our attention. We have now cited and discussed these works in the Introduction (lines 55-62 and 76-85) to better contextualize our study regarding bacterial motility and chemotaxis in confined geometries.

(2) Experimental setup:

a) The channels are built with asymmetric entrances (Figure 1), which could trigger a ratchet effect (because bacteria swim in circle) that could bias the rate at which cells enter into the channel, and which side they follow preferentially, especially for the narrow channel. Since the channel is short (160 µm), that would reflect on the statistics of cell distribution. Controls with straight entrances or with a reversed symmetry of the channel need to be performed to ensure that the reported results are not affected by this asymmetry.

We appreciate the reviewer's insight regarding the potential ratchet effect caused by asymmetric entrances. To rule this out, we fabricated a control device with straight entrances and repeated the measurements. As shown in Figure S3, the chemotactic drift velocity follows the same trend as observed in the original setup, confirming an optimal width of ~9 mm. These results demonstrate that the entrance geometry does not bias the reported statistics. We have updated the manuscript text at lines 233-235.

b) The authors say the motile bacteria accumulate mostly at the bottom surface. This is strange, for a small height of 30 µm, the bacteria should be more-or-less evenly spread between the top and bottom surface. How can this be explained?

We apologize for not explaining this clearly in the text. As shown by Wei et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 135, 188401 (2025), significant surface accumulation occurs in channels with heights exceeding 20 µm. In our specific experimental setup, we did not use Percoll to counteract gravity. Therefore, the bacteria accumulated mostly at the bottom surface under the combined influence of gravity and hydrodynamic attraction. This bottom-surface localization is supported by our observation that the bacterial trajectories were predominantly clockwise (characteristic of the bottom surface) rather than counter-clockwise (characteristic of the top surface). We have added this explanation to Line 141.

c) At the edge, some of the bacteria could escape up in the third dimension (http://doi.org/10.1039/c5sm00939a). What is the magnitude of this phenomenon in the current setup? Does it have an effect?

We thank the reviewer for raising this important point regarding 3D escape. We have quantified this phenomenon and found the escape rate from the edge into the third dimension to be 0.127 s-1. This corresponds to a mean residence time that allows a cell moving at 20 mm/s to travel approximately 157.5 mm along the edge. Since this distance is comparable to the full length of our lanes (~160 mm), most cells traverse the entire edge without escaping. Furthermore, our analysis is based on the average drift of the surface trajectories per unit of time; this metric is independent of the absolute number of cells present. Therefore, the escape phenomenon does not significantly impact our conclusions. We have added a statement clarifying this at line 154.

d) What is the cell density in the device? Should we expect cell-cell interactions to play a role here? If not, I would suggest to de-emphasize the connection to chemotaxis in the swarming paper in the introduction and discussion, which doesn't feel very relevant here, and rather focus on the other papers mentioned in point 1.

The cell density in our experiments was approximately 1.3×10-3 μm-2. Given this low density, we do not expect cell-cell interactions to play a role in the observed behaviors.

Regarding the connection to swarming chemotaxis: We agree that our low-density setup differs from a high-density swarm; however, we believe the comparison remains relevant for two reasons. First, it provides a necessary contrast to studies showing surface inhibition of chemotaxis. Second, while we eliminate cell-cell interactions, we isolate the geometric aspect of swarming. In a swarm, cells move within narrow lanes created by their neighbors. Our device mimics this specific physical confinement by replacing neighboring cells with PDMS sidewalls. This allows us to decouple the effects of physical confinement from cell-cell interactions. We have added the text (Line 370) to clarify this rationale and have incorporated the additional references in introduction as suggested in point 1.

e) We are not entirely convinced by the interpretation of the results in narrow channels. What is the causal relationship between the increased density on the RSW and the higher chemotactic drift? The authors seem to attribute higher drift to this increased RSW density, which emerges due to the geometric reasons. But if there is no initial bias, the same geometric argument would induce the same increased density of down-gradient swimmers on the LSW, and so, no imbalance between RSW and LSW density. Could it be the opposite that the increased RSW density results from chemotaxis (and maybe reinforces it), not the other way around? Confinement could then deplete one wall due to the proximity of the other, and/or modify the swimming pattern - 8 µm is very close to the size of the body + flagellum. To clarify this point, we suggest measuring the bacterial distributions in the absence of a gradient for all channel widths as a control.

We thank the reviewer for this insightful comment regarding the causal relationship between cell density and chemotactic drift. We apologize if the initial explanation was unclear.

Regarding the no-gradient control: Without an attractant gradient (and no initial bias), there is no breaking of symmetry and the labels of "LSW" and "RSW" are arbitrary. Therefore, there will be no asymmetry in the bacterial distributions on both sides (within experimental fluctuations) in the absence of a gradient for any channel width.

Regarding the causality and density imbalance: We agree that the increased RSW density is a result of chemotaxis, which is then reinforced by the lane geometry especially at narrow lane width. The mechanism relies on the coupling of chemotactic bias with surface circularity. The angle ranges that lead to RSW-UG accumulation (Fig. 6A-C) coincide with the up-gradient direction. Because these cells experience suppressed tumbling (longer runs), they can maintain the steady circular trajectories required to reach and align with the RSW. Conversely, while pure geometric analysis suggests a similar potential for LSW-DG accumulation, these trajectories coincide with the down-gradient direction. These cells experience enhanced tumbling, which distorts the circular trajectories. This prevents them from effectively reaching the LSW and also increases the probability of them leaving the wall. Therefore, the causality is indeed a positive feedback loop: the attractant gradient creates an initial bias that allows the RSW-UG fraction to form stable trajectories; the optimal lane width (matching the swimming radius) then maximizes this capture efficiency, further enriching the RSW fraction and enhancing the overall drift.

We have added clarifications regarding these points in the revised manuscript (the last paragraph of “Results”).

(3) Simulations:

The simulations treat the wall interaction very crudely. We would suggest treating it as a mechanical object that exerts elastic or "hard sphere" forces and torques on the bacteria for more realistic modeling.

We appreciate the reviewer's suggestion to incorporate more detailed mechanical interactions, such as elastic or hard-sphere forces, for the wall collisions. While we agree that a full hydrodynamic or mechanical model would offer higher fidelity, our experimental observations suggest that a simplified kinematic approach is sufficient for the specific phenomena studied here.

As shown in the new Fig. S2, our analysis of cell trajectories in the 44-µm-wide channels reveals that cells colliding with the sidewalls tend to align with the surface almost instantaneously. The timescale required for this alignment is negligible compared to the typical wall residence time (see also Ref. 6). Consequently, to maintain computational efficiency without sacrificing the essential physics of the accumulation effect, we employed a coarse-grained phenomenological model where a bacterium immediately aligns parallel to the wall upon contact, similar to approaches used previously (Ref. 43). We have added relevant text to the manuscript on lines 168-171.

Notably, the simulations have a constant (chemotaxis independent) rate of wall escape by tumbling. We would expect that reduced tumbling due to up-gradient motility induces a longer dwell time at the wall.

We apologize for the confusion. The chemotaxis effect is indeed fully integrated into our simulation. Specifically, the simulated cells sense the chemical gradient and adjust their motor CW bias (B) accordingly. This adjustment directly modulates the tumble rate (k), calculated as k = B/0.31 s-1. Consequently, the wall escape rate is not constant but varies with the chemotactic response. We also imposed a maximum detention time limit which, when combined with the variable tumble rate, results in an average wall residence time of approximately 2 s, consistent with our experimental observations (Fig. S6B). We have clarified these details in the final section of 'Materials and Methods'.

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

This paper addresses through experiment and simulation the combined effects of bacterial circular swimming near no-slip surfaces and chemotaxis in simple linear gradients. The authors have constructed a microfluidic device in which a gradient of L-aspartate is established to which bacteria respond while swimming while confined in channels of different widths. There is a clear effect that the chemotactic drift velocity reaches a maximum in channel widths of about 8 microns, similar in size to the circular orbits that would prevail in the absence of side walls. Numerical studies of simplified models confirm this connection.

The experimental aspects of this study are well executed. The design of the microfluidic system is clever in that it allows a kind of "multiplexing" in which all the different channel widths are available to a given sample of bacteria.

While the data analysis is reasonably convincing, I think that the authors could make much better use of what must be voluminous data on the trajectories of cells by formulating the mathematical problem in terms of a suitable Fokker-Planck equation for the probability distribution of swimming directions. In particular, I would like to see much more analysis of how incipient circular trajectories are interrupted by collisions with the walls and how this relates to enhanced chemotaxis. In essence, there needs to be a much clearer control analysis of trajectories without sidewalls to understand the mechanism in their presence.

We thank the reviewer for this insightful suggestion. We agree that understanding how circular trajectories are interrupted by wall collisions is central to explaining the enhanced chemotaxis. While we did not explicitly formulate a Fokker-Planck equation, we have addressed the reviewer's core point by employing two complementary mathematical approaches that model the probability distribution of swimming directions and wall interactions:

(1) Stochastic simulations (Langevin approach): As detailed in the "Simulation of E. coli chemotaxis within lane confinements" subsection of “Results” and Figure 5, we modeled cells as self-propelled particles performing random walks. This model explicitly accounts for the "interruption" of circular trajectories by incorporating a constant angular velocity (circular swimming) and an alignment effect upon collision with sidewalls. These simulations successfully reproduced the experimental trends, confirming that the interplay between circular radius and lane width determines the optimal drift velocity.

(2) Geometric probability analysis: To provide the "intuitive understanding", we included a specific Geometrical Analysis section (the last subsection of “Results”) and Figure 6. This analysis mathematically formulates the problem by calculating the exact proportion of swimming angles that allow a cell to transition from a circular trajectory in the bulk to an up-gradient trajectory along the Right Sidewall (RSW). By integrating over the possible swimming directions, we derived the probability of wall interception as a function of lane width (w) and swimming radius (r). This analysis reveals that the interruption of circular paths is most favorable for chemotaxis when w » (0.7-0.8)´r.

(3) Control analysis: regarding the "control analysis of trajectories without sidewalls," we utilized the cells in the Middle Area (MA) of the wide lanes as an internal control. As shown in Fig. 2B and 4A, these cells exhibit typical surface-associated circular swimming (Fig. 3B) but generate zero net drift. This serves as the baseline "no sidewall" condition, demonstrating that the chemotactic enhancement is strictly driven by the rectification of circular swimming into wall-aligned motion at the boundaries.

The authors argue that these findings may have relevance to a number of physiological and ecological contexts. Yet, each of these would be characterized by significant heterogeneity in pore sizes and geometries, and thus it is very unclear whether or how the findings in this work would carry over to those situations.

We thank the reviewer for this important observation regarding environmental heterogeneity. We agree that we should be cautious about directly extrapolating to complex ecological contexts without qualification. We have revised the last sentence of the abstract to adopt a more measured tone: "Our results may offer insights into bacterial navigation in complex biological environments such as host tissues and biofilms, providing a preliminary step toward exploring microbial ecology in confined habitats and potential strategies for controlling bacterial infections."

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for the authors):

Key elements of the mechanism of wall-directed chemotaxis are not sufficiently emphasized:

For instance, the chirality of the trajectories is an essential part of the analysis but is mentioned only briefly in the introduction. In the geometrical analysis, I understand that one of the critical parameters is the angle at which bacteria "collide" with the walls. But, again, this remains largely implicit in the discussion. This comes to the point that these ideas are not even mentioned in the abstract which doesn't provide any hint of a mechanism. An analysis of the actual trajectories of the cells after they hit the walls, as a function of their initial angle would be helpful in comparison with the simulations and the geometrical analysis.

We appreciate the reviewer's insightful comment regarding the need to better emphasize the mechanism of wall-directed chemotaxis. We agree that the chirality of trajectories and the geometry of wall collisions are central to our analysis and were previously under-emphasized.

To address this, we have made the following revisions:

(1) We have revised the Abstract (lines 25-27) and the Discussion (lines 391-393) to explicitly highlight the crucial role of chiral circular motion and the alignment effect following sidewall collisions.

(2) We further analyzed bacterial trajectories at different collision angles. Typical examples are shown in Supplementary Fig. S2. We observed that cells tend to align with and swim along the sidewalls regardless of their initial collision angles. This finding is now described in the main text at lines 168-171.

The motion of the bacteria is modelled as run-and-tumble at several places in the manuscript, and in particular in the simulations. Yet, the trajectories of the bacteria seem to be smooth in this almost 2D geometry, except of course when they directly interact with the walls (I hardly see tumbles in the MA region in Figure 1B). Can the authors elaborate on the assumptions made in the numerical simulations? In particular, how is the radius of the trajectories included in these equations of motion (line 514)?

We apologize for the lack of clarity regarding the bacterial motion model. It has been established that while bacteria do tumble near solid surfaces, they exhibit a smaller reorientation angle compared to bulk fluids; in fact, the most probable reorientation angle on a surface is zero (Ref. 41). Consequently, tumbles are often difficult to distinguish from runs with the naked eye. Additionally, the trajectories in Figure 1B are plotted on a 44 mm ´ 150 mm canvas with unequal coordinate scales, which may further obscure the visual distinctness of tumbling events.

Regarding the equations of motion: We modeled the bacteria as self-propelled particles governed by the internal chemotaxis pathway, alternating between run and tumble states. As noted in the equations on lines 286 & 578, we incorporated the circular motion by introducing a constant angular velocity, −ν0/r, during the run state. Here, ν0 represents the swimming speed, r denotes the radius of circular swimming, and the negative sign indicates clockwise chirality. Furthermore, to model the hydrodynamic interaction with the boundaries, we assumed that when a cell collides with a sidewall, its velocity vector instantly aligns parallel to that wall.

The comparison of Figure 5B (simulations) with Figure 4B (experiments) does not strike me as so "similar". Why are the points at small widths so noisy (Figure 5AB)? Figure 5C is cut at these widths, it should be plotted over the entire scale.

We acknowledge that the agreement between simulation and experiment is less robust in the narrowest channels. The discrepancy and "noise" at small widths in Figure 5 arise from the limitations of the self-propelled particle model in highly confined geometries. Specifically, our simulation treats bacteria as point particles and does not explicitly calculate the physical exclusion (steric effects) caused by the finite size of the flagella and cell body.

In the experimental setup, steric constraints within narrow channels (comparable to the cell size) restrict the cells' ability to turn freely, effectively stabilizing their motion. However, because our model allows particles to reorient more freely than actual cells would in such confined spaces, it produces fluctuations and an overestimation of the drift velocity at small widths. If these confinement effects were fully incorporated, the cell density mismatch between the left and right sidewalls would be reduced, leading to lower drift velocities that match the experimental data more closely.

Regarding Figure 5C: Since the "active particle" assumption loses physical validity in channels narrower than the scale of the bacterium, the simulation results in this regime are not representative of biological reality. Plotting these non-physical points would distort the analysis. Therefore, we have maintained the truncation of Figure 5C at 4 mm to ensure the data presented is physically meaningful. We have added a clear discussion of these model limitations to the manuscript at lines 310-314.

These important precisions should be added to the text or in a supplementary section. A validated mechanism describing in detail the impact of the walls on the cell trajectories would greatly improve the conclusions.

We thank the reviewer for the suggestions. As noted in the responses above, we have incorporated the details concerning the simulation assumptions and the model limitations at narrow widths into the revised manuscript. We have performed further analysis of the collision trajectories between bacteria and the sidewalls. As illustrated in the new Fig. S2, the data confirms that cells tend to align with and swim along the sidewalls following a collision, regardless of the initial impact angle.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors):

Minor points

(1) Related to swimming in 3D: The authors should specify the depth of field of the objective in their setup.

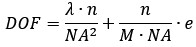

We thank the reviewer for pointing this out. We have calculated the depth of field (DOF) of our objective to be approximately 3.7 µm. This estimate is based on the standard formula:

where l = 610 nm (emission wavelength), n = 1.0 (refractive index), NA = 0.45 (numeric aperture), M = 20 (magnification), and e = 6.5 µm (camera resolution). We have added this specification to the "Microscopy and Data Acquisition" section of “Materials and Methods”.

(2) Related to the interpretation of the width effect: We think plotting the cell enrichment, ie the probabilities P in Figure 4B normalized to the expected value if cells were homogeneously distributed ((3µm)/w for the side walls, (w - 6µm)/w for the middle) would help understand the strength of the wall 'siphoning' effect.

We thank the reviewer for the suggestion. We have calculated the cell enrichment by normalizing the observed probabilities against the expected values for a homogeneous distribution, as suggested. The resulting relationship between cell enrichment and lane width is presented in Figure S4.

Related to simulations:

(1) Showing vd for the 3 regions in Figure S5 would be helpful also to understand the underlying mechanism.

We thank the reviewer for the suggestion. The Vd values for the three regions are shown in Fig. S5.

(2) Figure 5B vs 4B: There is a mismatch in the right vs left side density at w=6µm in the simulations that is not here in the experiments. What could explain this difference?

We appreciate the reviewer pointing this out. The mismatch in the simulations is due to the simplified treatment of cells as self-propelled particles, which overlooks the physical volume of the cell body and flagella. In narrow channels (w=6 mm), these physical constraints would restrict the cells' ability to change direction freely - a factor not fully captured in the simulation. Accounting for these steric effects would trap cells more effectively against the walls, reducing the density asymmetry between the LSW and RSW and lowering the drift velocity. This would bring the simulation results closer to the experimental observations. We have added a discussion of these limitations and effects to the revised manuscript (lines 310-314).

(3) The simulations essentially assume that the density of motile cells is homogeneous and equal at both x=0 and x=L open ends of the channel. Is it the case in the experiments, even with the gradient, and the walls creating some cell transport?

We thank the reviewer for pointing this out. The simulation assumption is consistent with our experimental observations. Our data were recorded within 160-μm-long lanes located in the center of the wider (400 μm) cell channel. In this central region, the cells maintain a continuous flux. Furthermore, experiments were performed within 8 min of flow, limiting the time for significant cell density gradients to establish. As illustrated in Author response image 11, the inhomogeneity in the measured cell density distribution is insignificant across the length of the observation window, indicating that the walls and gradient do not create significant heterogeneity at the boundaries of the region of interest.

Author response image 1.

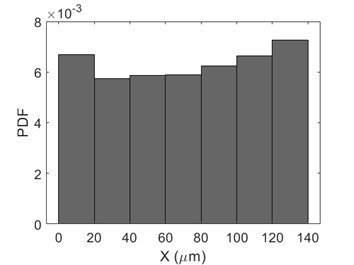

The cell density distribution along the gradient field from the data of 44-μm-wide lane.

(4) Line 506: There is something strange with the definition of the bias. B cannot be the tumbling bias if k=B/0.31 s-1 and the tumble-to-run rate is 5/s, because then the tumbling bias is B/0.31 / (B/0.31 + 5). Please clarify.

We apologize for the confusion caused by the notation. In our model, B represents the CW bias of the individual flagellar motor, not the macroscopic tumbling bias of the cell. We assume the run-to-tumble rate is equivalent to the motor CCW-to-CW switching rate (k). Previous studies have shown that this rate increases linearly with the motor CW bias according to k=B/t, where t is a characteristic time (Ref. 50).

Based on experimental data for wildtype cells, the average run time in the near-surface region is ~2.0 s (corresponding to a run-to-tumble rate of ~0.5 s-1) (Ref. 11), and the steady-state wildtype CW bias is ~0.15. Using these values, we determined t ~ 0.31 s. Consequently, the switching rate is defined as k=B/0.31 s-1. Since the tumble duration is constant (0.2 s) (Ref. 51), the tumble-to-run rate is fixed at 5 s-1. We have clarified these definitions and parameter values in lines 569-573.

Other minor comments:

(1) Line 20 and lines 34-35: We think that the connection to infection is questionable here and should be toned down.

Thank you for the suggestion. We have revised Line 20 to read: “Understanding bacterial behavior in confined environments is helpful to elucidating microbial ecology and developing strategies to manage bacterial infections.” Additionally, we modified lines 34-35 to state: “Our results may offer insights into bacterial navigation in complex biological environments such as host tissues and biofilms, providing a preliminary step toward exploring microbial ecology in confined habitats and potential strategies for controlling bacterial infections.”

(2) Line 49: Consider highlighting the change in the sense of rotation at the air-liquid interface.

Thank you for the suggestion. We have now highlighted the difference in chirality between trajectories at the air-liquid interface and those at the liquid-solid interface. The text has been updated to read: “For example, E. coli swim clockwise when observed from above a solid surface, whereas Caulobacter crescentus move in tight, counter-clockwise circles when viewed from the liquid side.”

(3) Lines 58-59: The sentence should be better formulated, explaining what is CheY-P and that its concentration changes because of a change in phosphorylation (P).

Thank you for the suggestion. We have reformulated this section to explicitly define CheY-P and explain how its concentration is regulated through phosphorylation. The revised text reads: “The transmembrane chemoreceptors detect attractants or repellents and transmit signals into the cell by modulating the autophosphorylation of the histidine kinase CheA. Attractant binding suppresses CheA autophosphorylation, while repellent binding promotes it. This modulation alters the concentration of the phosphorylated response regulator protein, CheY-P.”

(4) Lines 63-64: CheR CheB do a bit more than "facilitating" adaptation, they mediate it. The notation CheB(p) may be confusing, since "-P" was used above for CheY.

Thank you for pointing this out. We have corrected the notation and strengthened the description of the enzymes' roles. The revised text is: “The adaptation enzymes CheR and CheB methylate and demethylate the receptors, respectively, mediating sensory adaptation.”

(5) Line 130: there must be a typo in the formula.

We have replaced the ambiguous lag time variable in Fig. 1C with nΔt to ensure mathematical consistency.

(6) Additionally, \Delta t is both the time between the frame here and the lag time in Figure 1.

Thank you for highlighting this ambiguity. We have updated the notation to distinguish these two values. The lag time in Figure 1 is now explicitly denoted as nΔt, while Δt remains the time interval between individual frames.

(7) Line 162: "Consistent with previous reports," a reference to said reports is missing.

Thank you for pointing this out. We have now added the reference (Ref. 41) to support this statement.

(8) Figure 1B: Are these tracks in the presence of a gradient? Same as used in panel C? This needs to be explained.

Response: Thank you for this question. We confirm that the tracks shown in Figure 1B were indeed recorded in the presence of a gradient and represent a subset of the data used in Figure 1C. We have clarified this in the figure legend as follows: "Thirty bacterial trajectories selected from the data of the 44-mm-wide lane in gradient assays. These represent a subset of the trajectories analyzed in panel C."

(9) Simulations: the equation for x(t) should also be given for completeness.

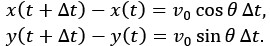

Thank you for the suggestion. For completeness, we have added the position updating equations for the run state to the Materials and Methods section (lines 579-580). The equations are defined as:

(10) Figure S2: For the swimming directions that are more unstable due to the surface friction torque, RSW-DG, and LSW-UG, one would have expected that the Up-gradient motion is more persistent than the down gradient one. It seems to be the opposite. Is it significant, and what could be the reason for this?

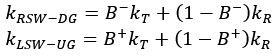

We apologize for the lack of clarity in our original explanation. While we would generally expect up-gradient motion to be more persistent than down-gradient motion in bulk fluid, our measurements near the surface show a different trend due to the specific contributions of run and tumble states to the escape rate. Cells swimming up-gradient (UG) in the LSW experience higher probability of running. Consequently, they are subjected to the destabilizing surface friction torque for a greater proportion of time compared to cells swimming down-gradient (DG) in the RSW. This can be explained mathematically. The escape rates for RSW-DG and LSW-UG can be expressed as:

Where B+ and B− represent the tumble bias (probability of tumbling) when swimming up-gradient and down-gradient, respectively, and kT and kR denote the escape rates during a tumble and a run, respectively. Due to the chemotactic response, 0≤ B+< B− ≤1. Crucially, our system is characterized by kR>kT (the escape rate is higher during a run than a tumble). Therefore, the lower tumble bias during up-gradient swimming (B+< B−) increases the weight of the run-state escape term((1−B+)kR), leading to a higher overall escape rate for LSW-UG compared to RSW-DG. We have added an intuitive understanding of kR>kT in the Supplemental text.

-

-

-

eLife Assessment

This valuable study examines the effects of side-wall confinement on the chemotaxis of swimming bacteria in a shallow microfluidic channel. The authors present solid experimental evidence, combined with geometric analysis and numerical simulations of simplified models, showing that chemotaxis is enhanced when the distance between the side walls is comparable to the intrinsic radius of circular swimming near open surfaces. This study should be of interest to scientists specializing in bacteria-surface interactions.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

This article deals with the chemotactic behavior of E coli bacteria in thin channels (a situation close to 2D). It combines experiments and simulations.

The authors show experimentally that, in 2D, bacteria swim up a chemotactic gradient much more effectively when they are in the presence of lateral walls. Systematic experiments identify an optimum for chemotaxis for a channel width of ~8µm, close to the average radius of the circle trajectories of the unconfined bacteria in 2D. It is known that these circles are chiral and impose that the bacteria swim preferentially along the right-side wall when there is no chemotactic gradient. In the presence of a chemotactic gradient, this larger proportion of bacteria swimming on the right wall yields chemotaxis. This effect is backed by numerical simulations and a …

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

This article deals with the chemotactic behavior of E coli bacteria in thin channels (a situation close to 2D). It combines experiments and simulations.

The authors show experimentally that, in 2D, bacteria swim up a chemotactic gradient much more effectively when they are in the presence of lateral walls. Systematic experiments identify an optimum for chemotaxis for a channel width of ~8µm, close to the average radius of the circle trajectories of the unconfined bacteria in 2D. It is known that these circles are chiral and impose that the bacteria swim preferentially along the right-side wall when there is no chemotactic gradient. In the presence of a chemotactic gradient, this larger proportion of bacteria swimming on the right wall yields chemotaxis. This effect is backed by numerical simulations and a geometrical analysis.

If the conclusions drawn from the experiments presented in this article seem clear and interesting, I find that the key elements of the mechanism of this wall-directed chemotaxis are not sufficiently emphasized. Moreover, the paper would be clearer with more details on the hypotheses and the essential ingredients of the analyses.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

In this study, the authors investigated the chemotaxis of E. coli swimming close to the bottom surface in gradients of attractant in channels of increasingly smaller width but fixed height = 30 µm and length ~160 µm. In relatively large channels, they find that on average the cells drift in response to the gradient, despite cells close to the surface away from the walls being known to not be chemotactic because they swim in circles.

They find that this average drift is due to the cell localization close to the side walls, where they slide along the wall. Whereas the bacteria away from the walls have no chemotaxis (as shown before), the ones on the left side wall go down-gradient on average, but the ones on the right side wall go up-gradient faster, hence the average drift. They then study the effect …

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

In this study, the authors investigated the chemotaxis of E. coli swimming close to the bottom surface in gradients of attractant in channels of increasingly smaller width but fixed height = 30 µm and length ~160 µm. In relatively large channels, they find that on average the cells drift in response to the gradient, despite cells close to the surface away from the walls being known to not be chemotactic because they swim in circles.

They find that this average drift is due to the cell localization close to the side walls, where they slide along the wall. Whereas the bacteria away from the walls have no chemotaxis (as shown before), the ones on the left side wall go down-gradient on average, but the ones on the right side wall go up-gradient faster, hence the average drift. They then study the effect of reducing channel width. They find that chemotaxis is higher in channels with a width of about 8 µm, which approximately corresponds to the radius of the circular swimming R. This higher chemotactic drift is concomitant to an increased density of cells on the RSW. They do simulations and modeling to suggest that the disruption of circular swimming upon collision with the wall increases the density of cells on the RSW, with a maximal effect at w = ~ 2/3 R, which is a good match for their experiments.

Strengths:

The overall result that confinement at the edge stabilises bacterial motion and allows chemotaxis is very interesting although not entirely unexpected. It is also important for understanding bacterial motility and chemotaxis under ecologically relevant conditions, where bacteria frequently swim under confinement (although its relevance for controlling infections could be questioned). The experimental part of the study is nicely supported by the model.

Weaknesses:

Several points of this study, in particular the interpretation of the width effect, need better clarification:

(1) Context:

There are a number of highly relevant previous publications that should have been acknowledged and discussed in relation to the current work:

https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2023/sm/d3sm00286a

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1140/epje/s10189-024-00450-7

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2022.04.008

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1816315116

https://www.pnas.org/doi/full/10.1073/pnas.0907542106

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15711-0

http://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15711-0

http://doi.org/10.1039/c5sm00939a(2) Experimental setup:

a) The channels are built with asymmetric entrances (Figure 1), which could trigger a ratchet effect (because bacteria swim in circle) that could bias the rate at which cells enter into the channel, and which side they follow preferentially, especially for the narrow channel. Since the channel is short (160 µm), that would reflect on the statistics of cell distribution. Controls with straight entrances or with a reversed symmetry of the channel need to be performed to ensure that the reported results are not affected by this asymmetry.

b) The authors say the motile bacteria accumulate mostly at the bottom surface. This is strange, for a small height of 30 µm, the bacteria should be more-or-less evenly spread between the top and bottom surface. How can this be explained?

c) At the edge, some of the bacteria could escape up in the third dimension (http://doi.org/10.1039/c5sm00939a). What is the magnitude of this phenomenon in the current setup? Does it have an effect?

d) What is the cell density in the device? Should we expect cell-cell interactions to play a role here? If not, I would suggest to de-emphasize the connection to chemotaxis in the swarming paper in the introduction and discussion, which doesn't feel very relevant here, and rather focus on the other papers mentioned in point 1.

e) We are not entirely convinced by the interpretation of the results in narrow channels. What is the causal relationship between the increased density on the RSW and the higher chemotactic drift? The authors seem to attribute higher drift to this increased RSW density, which emerges due to the geometric reasons. But if there is no initial bias, the same geometric argument would induce the same increased density of down-gradient swimmers on the LSW, and so, no imbalance between RSW and LSW density. Could it be the opposite that the increased RSW density results from chemotaxis (and maybe reinforces it), not the other way around? Confinement could then deplete one wall due to the proximity of the other, and/or modify the swimming pattern - 8 µm is very close to the size of the body + flagellum. To clarify this point, we suggest measuring the bacterial distributions in the absence of a gradient for all channel widths as a control.

(3) Simulations:

The simulations treat the wall interaction very crudely. We would suggest treating it as a mechanical object that exerts elastic or "hard sphere" forces and torques on the bacteria for more realistic modeling. Notably, the simulations have a constant (chemotaxis independent) rate of wall escape by tumbling. We would expect that reduced tumbling due to up-gradient motility induces a longer dwell time at the wall.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

This paper addresses through experiment and simulation the combined effects of bacterial circular swimming near no-slip surfaces and chemotaxis in simple linear gradients. The authors have constructed a microfluidic device in which a gradient of L-aspartate is established to which bacteria respond while swimming while confined in channels of different widths. There is a clear effect that the chemotactic drift velocity reaches a maximum in channel widths of about 8 microns, similar in size to the circular orbits that would prevail in the absence of side walls. Numerical studies of simplified models confirm this connection.

The experimental aspects of this study are well executed. The design of the microfluidic system is clever in that it allows a kind of "multiplexing" in which all the different channel …

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

This paper addresses through experiment and simulation the combined effects of bacterial circular swimming near no-slip surfaces and chemotaxis in simple linear gradients. The authors have constructed a microfluidic device in which a gradient of L-aspartate is established to which bacteria respond while swimming while confined in channels of different widths. There is a clear effect that the chemotactic drift velocity reaches a maximum in channel widths of about 8 microns, similar in size to the circular orbits that would prevail in the absence of side walls. Numerical studies of simplified models confirm this connection.

The experimental aspects of this study are well executed. The design of the microfluidic system is clever in that it allows a kind of "multiplexing" in which all the different channel widths are available to a given sample of bacteria.

While the data analysis is reasonably convincing, I think that the authors could make much better use of what must be voluminous data on the trajectories of cells by formulating the mathematical problem in terms of a suitable Fokker-Planck equation for the probability distribution of swimming directions. In particular, I would like to see much more analysis of how incipient circular trajectories are interrupted by collisions with the walls and how this relates to enhanced chemotaxis. In essence, there needs to be a much clearer control analysis of trajectories without sidewalls to understand the mechanism in their presence.

The authors argue that these findings may have relevance to a number of physiological and ecological contexts. Yet, each of these would be characterized by significant heterogeneity in pore sizes and geometries, and thus it is very unclear whether or how the findings in this work would carry over to those situations.

-

-