PA28γ promotes the malignant progression of tumor by elevating mitochondrial function via C1QBP

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

eLife Assessment

This manuscript determines how PA28g, a proteasome regulator that is overexpressed in tumors, and C1QBP, a mitochondrial protein for maintaining oxidative phosphorylation that plays a role in tumor progression, interact in tumor cells to promote their growth, migration and invasion. Additional experiments and analyses that supported the theoretical models for the interaction have been performed in response to the reviews. The overall findings and conceptual framework are important and the evidence is solid. A logical extrapolation of this work is to test the C1QBP mutants using functional assays to determine whether the mutations can decrease the protein stability mediated by the interaction with PA28g.

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

Proteasome activator 28γ (PA28γ) plays a critical role in malignant progression of various tumors, however, its role and regulation are not well understood. Here, using oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) as the main research model, and combining co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP), proximity ligation assays (PLA), AlphaFold 3-based molecular docking, and truncation constructs, we discovered that PA28γ interacted with complement 1q binding protein (C1QBP). This interaction is dependent on the C1QBP N-terminus (aa 1–167) rather than the known functional domain. Point mutation in C1QBP (T76A/G78N) disrupting predicted hydrogen bonding with PA28γ-D177 significantly reduced their binding. Notably, we found that PA28γ enhances C1QBP protein stability in OSCC. Functionally, PA28γ and C1QBP co-localized in mitochondria, promoting fusion (via upregulation of OPA1, MFN1/2), respiratory complex expression, oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS), ATP production, and ROS generation. Crucially, PA28γ-enhanced OSCC cell migration, invasion, and proliferation in vitro were dependent on C1QBP. In vivo, orthotopic OSCC models showed Pa28γ overexpression increased tumor growth and elevated C1qbp levels, correlating with elevated ATP and ROS. Using transgenic Psme3 -/- mice and subcutaneous tumor grafts, we confirmed that silencing of Pa28γ suppresses tumor growth, reduces C1qbp levels, and dampens mitochondrial metabolism—specifically in knockout hosts. Clinically, PA28γ and C1QBP expression were positively correlated during oral carcinogenesis and in metastatic OSCC tissues across cohorts. High co-expression predicted poor prognosis in OSCC patients. Thus, PA28γ stabilizes C1QBP via N-terminal interaction to drive mitochondrial OXPHOS and tumor progression, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target.

Article activity feed

-

-

-

eLife Assessment

This manuscript determines how PA28g, a proteasome regulator that is overexpressed in tumors, and C1QBP, a mitochondrial protein for maintaining oxidative phosphorylation that plays a role in tumor progression, interact in tumor cells to promote their growth, migration and invasion. Additional experiments and analyses that supported the theoretical models for the interaction have been performed in response to the reviews. The overall findings and conceptual framework are important and the evidence is solid. A logical extrapolation of this work is to test the C1QBP mutants using functional assays to determine whether the mutations can decrease the protein stability mediated by the interaction with PA28g.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors tried to determine how PA28g functions in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cells. They hypothesized it may act through metabolic reprogramming in the mitochondria.

Strengths:

They found that the genes of PA28g and C1QBP are in an overlapping interaction network after an analysis of a genome database. They also found that the two proteins interact in coimmunoprecipitation and pull-down assays using the lysate from OSCC cells with or without expression of the exogenous genes. They used truncated C1QBP proteins to map the interaction site to the N-terminal 167 residues of C1QBP protein. They observed the levels of the two proteins are positively correlated in the cells. They provided evidence for the colocalization of the two proteins in the mitochondria and the effect on mitochondrial …

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors tried to determine how PA28g functions in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cells. They hypothesized it may act through metabolic reprogramming in the mitochondria.

Strengths:

They found that the genes of PA28g and C1QBP are in an overlapping interaction network after an analysis of a genome database. They also found that the two proteins interact in coimmunoprecipitation and pull-down assays using the lysate from OSCC cells with or without expression of the exogenous genes. They used truncated C1QBP proteins to map the interaction site to the N-terminal 167 residues of C1QBP protein. They observed the levels of the two proteins are positively correlated in the cells. They provided evidence for the colocalization of the two proteins in the mitochondria and the effect on mitochondrial form and function in vitro and in vivo OSCC models, and the correlation of the protein expression with the prognosis of cancer patients.

Comments on revision:

The third revision added data from two point mutations of C1QBP that would disrupt a hydrogen bond network with PA28g protein. As one would expect from the structural models obtained with AlphaFold, the interaction between the two proteins as detected by co-immunoprecipitation of cell lysate was reduced by both mutations. Therefore, the theoretical models for the interaction were supported by the experimental data. Moving forward, the home run experiments would be to test the C1QBP mutants in functional assays to determine whether the mutations can decrease the protein stability afforded by the interaction with PA28g, which in turn decrease the effect of PA28g on mitochondria and tumor cells via C1QBP. Success of these experiments will conclude this manuscript that presents a novel finding for tumor cell biology which could be a launch pad for therapeutic intervention of tumor development.

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

This manuscript determines how PA28g, a proteasome regulator that is overexpressed in tumors, and C1QBP, a mitochondrial protein for maintaining oxidative phosphorylation that plays a role in tumor progression, interact in tumor cells to promote their growth, migration and invasion. Evidence for the interaction and its impact on mitochondrial form and function was provided although it is not particularly strong.

The revised manuscript corrected mislabeled data in figures and provides more details in figure legends. Misleading sentences and typos were corrected. However, key experiments that were suggested in previous reviews were not done, such as making point mutations to disrupt the protein interactions and …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

This manuscript determines how PA28g, a proteasome regulator that is overexpressed in tumors, and C1QBP, a mitochondrial protein for maintaining oxidative phosphorylation that plays a role in tumor progression, interact in tumor cells to promote their growth, migration and invasion. Evidence for the interaction and its impact on mitochondrial form and function was provided although it is not particularly strong.

The revised manuscript corrected mislabeled data in figures and provides more details in figure legends. Misleading sentences and typos were corrected. However, key experiments that were suggested in previous reviews were not done, such as making point mutations to disrupt the protein interactions and assess the consequence on protein stability and function. Results from these experiments are critical to determine whether the major conclusions are fully supported by the data.

The second revision of the manuscript included the proximity ligation data to support the PA28g-C1QBP interaction in cells. However, the method and data were not described in sufficient detail for readers to understand. The revision also includes the structural models of the PA28g-C1QBP complex predicted by AlphaFold. However, the method and data were not described with details for readers to understand how this structural modeling was done, what is the quality of the resulting models, and the physical nature of the protein-protein interaction such as what kind of the non-covalent interactions exist in the interface of the protein complexes. Furthermore, while the interactions mediated by the protein fragments were tested by pull-down experiments, the interactions mediated by the three residues were not tested by mutagenesis and pull-down experiments. In summary, the revision was improved, but further improvement is needed.

Thank you very much for your comments.

(1) Based on your suggestion, we predicted the possible interaction sites using AlphaFold 3 and found that mutations in amino acids 76 and 78 of C1QBP affect the interaction with PA28γ (Revised Appendix Figure 1J). Subsequently, pulldown experiment also found that after mutating the amino acids at the two aforementioned sites (T76A, G78N), C1QBP that could bind to PA28γ decreased (Revised Figure 1J). The above results confirm that PA28γ could interacts with C1QBP, in a manner dependent on the N-terminus of C1QBP. These findings are now included in the revised manuscript “In addition, we employed AlphaFold 3 to perform energy minimization and predict hydrogen bonds between the C1QBP N-terminus (amino acids 1-167) and the PA28γ protein interaction region. The results suggest that the T76 and G78 residues of C1QBP may be key contributors to the interaction. Consistently, coimmunoprecipitation analysis demonstrated that mutations at these sites (C1QBPT76A and C1QBPG78N) significantly reduced the binding ability to PA28γ (Fig. 1J and Appendix Fig. 1J)”, specifically in results section. We believe this additional validation strengthens the robustness of our findings.

(2) According to your suggestion, we have added a description of the results of PLA in the figure legend (Revised Figure 1C) and the method of PLA in the appendix file (Revised Appendix file, Part “Proximity Ligation Assay”). The revised text reads as follows: (C) PLA image of UM1 cells shows the interaction between C1QBP and PA28γ in both cytoplasm and nucleus (red fluorescence).

(3) In the light of your suggestion, we have enriched the description of AlphaFold 3 analysis in the appendix file (Revised Appendix file, Page 10-11). The revised text reads as follows:

“Prediction and Analysis of Protein Interactions

Protein Sequence Retrieval and Structure Prediction

The protein sequences of C1QBP and PA28γ were obtained from the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database. Structural predictions of the protein-protein interaction between C1QBP and PA28γ were conducted using AlphaFold 3. The plDDT (predicted local distance difference test) values were utilized to assess the confidence of the predicted models. Models with a plDDT score above 70 were considered confident, while those with a score above 90 were categorized as very high confidence. These values were annotated in the figures to indicate the reliability of the structural predictions.”

“Protein Preparation and Structure Optimization

The best-scored model for the C1QBP-PA28γ interaction predicted by AlphaFold 3 was selected for further analysis. The model was imported into MOE 2022 (Molecular Operating Environment) software for protein preparation. This process included the removal of water molecules and other heteroatoms, followed by the addition of hydrogen atoms to the structure. This step was essential for optimizing the protein’s 3D conformation and ensuring the correctness of the protonation states at physiological pH.”

“Energy Minimization and Hydrogen Bond Prediction

The protein structure was subjected to energy minimization using the Amber10: EHT (Effective Hamiltonian Theory) force field, with R-field 1: 80 settings to refine the model’s geometry. The minimization process was performed to optimize the protein’s internal energy and ensure stable conformation, followed by calculation of hydrogen bond interactions. The interaction energies and hydrogen bonds were analyzed to identify potential binding sites and stabilize the predicted protein-protein complex.”

-

-

-

eLife Assessment

This work attempts to demonstrate an ATP-independent non-canonical role of proteasomal component PA28y in the promotion of oral squamous cell carcinoma growth, migration, and invasion. Although the authors have addressed some concerns, uncertainties regarding the PA28g-C1QBP direct interaction still exist. The overall findings of the manuscript are useful, but the validation evidence is incomplete.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

This manuscript determines how PA28g, a proteasome regulator that is overexpressed in tumors, and C1QBP, a mitochondrial protein for maintaining oxidative phosphorylation that plays a role in tumor progression, interact in tumor cells to promote their growth, migration and invasion. Evidence for the interaction and its impact on mitochondrial form and function was provided although it is not particularly strong.

The revised manuscript corrected mislabeled data in figures and provides more details in figure legends. Misleading sentences and typos were corrected. However, key experiments that were suggested in previous reviews were not done, such as making point mutations to disrupt the protein interactions and assess the consequence on protein stability and function. Results from these experiments are …

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

This manuscript determines how PA28g, a proteasome regulator that is overexpressed in tumors, and C1QBP, a mitochondrial protein for maintaining oxidative phosphorylation that plays a role in tumor progression, interact in tumor cells to promote their growth, migration and invasion. Evidence for the interaction and its impact on mitochondrial form and function was provided although it is not particularly strong.

The revised manuscript corrected mislabeled data in figures and provides more details in figure legends. Misleading sentences and typos were corrected. However, key experiments that were suggested in previous reviews were not done, such as making point mutations to disrupt the protein interactions and assess the consequence on protein stability and function. Results from these experiments are critical to determine whether the major conclusions are fully supported by the data.

The second revision of the manuscript included the proximity ligation data to support the PA28g-C1QBP interaction in cells. However, the method and data were not described in sufficient detail for readers to understand. The revision also includes the structural models of the PA28g-C1QBP complex predicted by AlphaFold. However, the method and data were not described with details for readers to understand how this structural modeling was done, what is the quality of the resulting models, and the physical nature of the protein-protein interaction such as what kind of the non-covalent interactions exist in the interface of the protein complexes. Furthermore, while the interactions mediated by the protein fragments were tested by pull-down experiments, the interactions mediated by the three residues were not tested by mutagenesis and pull-down experiments. In summary, the revision was improved, but further improvement is needed

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Comment of Review of Revised Version:

Although the authors have partly corrected the manuscript by removing the mislabeling in their Co-IP experiments, my primary concern on the actual functional connotations and direct interaction between PA28y and C1QBP still remains unaddressed. As already mentioned in my previous review, since the core idea of the work is PA28y's direct interaction with C1QBP, stabilizing it, the same should be demonstrated in a more convincing manner.

My other observation on the detection of C1QBP as a doublet has been addressed by usage of anti-C1QBP Monoclonal antibody against the polyclonal one used before. C1QBP doublets have not been observed in the present case.

The authors have also …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the previous reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Comment of Review of Revised Version:

Although the authors have partly corrected the manuscript by removing the mislabeling in their Co-IP experiments, my primary concern on the actual functional connotations and direct interaction between PA28y and C1QBP still remains unaddressed. As already mentioned in my previous review, since the core idea of the work is PA28y's direct interaction with C1QBP, stabilizing it, the same should be demonstrated in a more convincing manner.

My other observation on the detection of C1QBP as a doublet has been addressed by usage of anti-C1QBP Monoclonal antibody against the polyclonal one used before. C1QBP doublets have not been observed in the present case.

The authors have also worked on the presentation of the background by suitably modifying the statements and incorporating appropriate citations.

However, the authors are requested to follow the recommendations provided to them by the reviewers to address the major concerns.

Thank you very much for your comments. We appreciate your concerns regarding the need for more direct evidence to support the stabilizing interaction between PA28γ and C1QBP. In response to your feedback, we have taken additional steps to provide more convincing evidence of this interaction.

To complement our existing pull-down and Co-IP experiments, we utilized AlphaFold 3 to predict the three-dimensional structure of the PA28γ-C1QBP complex. The predicted model reveals specific residues and interfaces that are likely involved in the direct interaction between PA28γ and C1QBP. Our analysis indicates that this interaction may depend on amino acids 1-167 and 1-213 of C1QBP (Revised Appendix Figure 1E-H). Furthermore, aspartate (ASP), as the 177th amino acids of PA28γ, was predicted to interact with the 76th amino acid threonine (THR) and the 78th amino acid glycine (GLY) of C1QBP (Revised Appendix Figure 1I). This structural insight was further validated by our immunoprecipitation experiments (Revised Figure 1J). These findings provide a molecular basis for the observed stabilizing effect and suggest potential mechanisms by which PA28γ influences C1QBP stability. Specifically, the identified interaction sites offer clues into how PA28γ may stabilize C1QBP at the molecular level.

Furthermore, we performed proximity ligation assays (PLA) to detect in situ interactions between PA28γ and C1QBP at the single-cell level. PLA results clearly demonstrate the presence of PA28γ-C1QBP complexes within cells, providing direct evidence of their physical interaction (Revised Figure 1D). This approach overcomes some of the limitations associated with traditional IP experiments and confirms the direct nature of the interaction.

In summary, the integration of AlphaFold 3 predictions, PLA data, and our previous Pull-down and Co-IP experiments provides robust and direct evidence for a stable interaction between PA28γ and C1QBP. We believe that these additional findings significantly reinforce our conclusions and effectively address the concerns raised by the reviewers. Once again, thank you for your valuable feedback, which has been instrumental in refining and enhancing our study.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Comment of Review of Revised Version:

Weaknesses:

Many data sets are shown in figures that cannot be understood without more descriptions either in the text or the legend, e.g., Fig. 1A. Similarly, many abbreviations are not defined.

The revision addressed these issues.

Some of the pull-down and coimmunoprecipitation data do not support the conclusion about the PA28g-C1QBP interaction. For example, in Appendix Fig. 1B the Flag-C1QBP was detected in the Myc beads pull-down when the protein was expressed in the 293T cells without the Myc-PA28g, suggesting that the pull-down was not due to the interaction of the C1QBP and PA28g proteins. In Appendix Fig. 1C, assume the SFB stands for a biotin tag, then the SFB-PA28g should be detected in the cells expressing this protein after pull-down by streptavidin; however, it was not. The Western blot data in Fig. 1E and many other figures must be quantified before any conclusions about the levels of proteins can be drawn.

The revision addressed these problems.

The immunoprecipitation method is flawed as it is described. The antigen (PA28g or C1QBP) should bind to the respective antibody that in turn should binds to Protein G beads. The resulting immunocomplex should end up in the pellet fraction after centrifugation, and analyzed further by Western blot for coprecipitates. However, the method in the Appendix states that the supernatant was used for the Western blot.

The revision corrected this method.

To conclude that PA28g stabilizes C1QBP through their physical interaction in the cells, one must show whether a protease inhibitor can substitute PA28q and prevent C1QBP degradation, and also show whether a mutation that disrupt the PA28g-C1QBP interaction can reduce the stability of C1QBP. In Fig. 1F, all cells expressed Myc-PA28g. Therefore, the conclusion that PA28g prevented C1QBP degradation cannot be reached. Instead, since more Myc-PA28g was detected in the cells expressing Flag-C1QBP compared to the cells not expressing this protein, a conclusion would be that the C1QBP stabilized the PA28g. Fig. 1G is a quantification of a Western blot data that should be shown.

The binding site for PA28g in C1QBP was mapped to the N-terminal 167 residues using truncated proteins. One caveat would be that some truncated proteins did not fold correctly in the absence of the sequence that was removed. Thus, the C-terminal region of the C1QBP with residues 168-283 may still bind to the PA29g in the context of full-length protein. In Fig. 1I, more Flag-C1QBP 1-167 was pull-down by Myc-PA28g than the full-length protein or the Flag-C1QBP 1-213. Why?

The interaction site in PA28g for C1QBP was not mapped, which prevents further analysis of the interaction. Also, if the interaction domain can be determined, structural modeling of the complex would be feasible using AlphaFold2 or other programs. Then, it is possible to test point mutations that may disrupt the interaction and if so, the functional effect.

The revision added AlphaFold models for the protein interaction. However, the models were not analyzed and potential mutations that would disrupt the interact were not predicted, made and tested. The revision did not addressed the request for the protease inhibitor.

Thank you for your insightful comments regarding the binding site of PA28γ in C1QBP. We appreciate your concern about the potential misfolding of truncated proteins and the possible interaction between the C-terminal region (residues 168-283) of C1QBP and PA28γ in the context of full-length protein.

To address these concerns, we have conducted additional analyses and experiments to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the interaction between PA28γ and C1QBP. Using AlphaFold 3, we predicted the three-dimensional structure of the PA28γ-C1QBP complex. The model reveals specific residues and interfaces that are likely involved in the direct interaction between PA28γ and C1QBP. Notably, our structural analysis indicates that the interaction may primarily depend on amino acids 1-167 and 1-213 of C1QBP (Revised Appendix Figure 1E-H). Furthermore, aspartate (ASP), as the 177th amino acids of PA28γ, was predicted to interact with the 76th amino acid threonine (THR) and the 78th amino acid glycine (GLY) of C1QBP (Revised Appendix Figure 1I). This prediction supports the idea that the N-terminal region of C1QBP is crucial for its interaction with PA28γ. Regarding the observation in old Figure 1I (Revised Figure 1J), where more Flag-C1QBP 1-167 was pulled down by Myc-PA28γ compared to the full-length protein or Flag-C1QBP 1-213, we believe this can be explained by several factors:

A. The truncation of C1QBP to residues 1-167 may expose key interaction sites that are partially obscured in the full-length protein. This enhanced accessibility could lead to stronger binding affinity and higher pull-down efficiency.

B. While it is possible that some truncated proteins do not fold correctly, our data suggest that the N-terminal fragment (1-167) retains sufficient structural integrity to interact effectively with PA28γ. The increased pull-down of this fragment suggests that it captures the essential elements required for binding.

C. The C-terminal region (168-283) might exert steric hindrance or allosteric effects on the N-terminal binding site in the context of the full-length protein. This interference could reduce the overall binding efficiency, leading to less pull-down of full-length C1QBP compared to the truncated version.

Compared with the control group, the presence of Myc-PA28γ significantly increased the expression level of Flag-C1QBP (r Revised Figure 1G). Gray value analysis showed that in cells transfected with Myc-PA28γ, the decay rate of Flag-C1QBP was significantly slower than that of the control group (Revised Figure 1H), suggesting that PA28γ can delay the protein degradation of C1QBP and stabilize its protein level. This indicates that an increase in the level of PA28γ protein can significantly enhance the expression level of C1QBP protein, while PA28γ can slow down the degradation rate of C1QBP and improve its stability. In addition, our western blot analysis also proved that PA28γ could still prevent the degradation of C1QBP under the action of proteasome inhibitor MG-132 (Revised Appendix Figure 1D). Moreover, PA28γ could not stabilize the mutation of C-terminus of C1QBP (amino acids 94-282), which was not the interaction domain of PA28γ-C1QBP (Revised Figure 1K).

-

-

eLife Assessment

This work attempts to demonstrate an ATP-independent non-canonical role of proteasomal component PA28y in the promotion of oral squamous cell carcinoma growth, migration, and invasion. The evidence remains incomplete and the work would benefit from further experimental work. The authors have not adequately addressed the reviewers' comments.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

The manuscript the authors have tried to dissect the functions of Proteasome activator 28γ (PA28γ) which is known to activate proteosomal function in an ATP independent manner. Although there are multiple works that have highlighted the role of this protein in tumour, this study specifically tried to develop a correlate with Complement C1q binding protein (C1QBp) that is associated with immune response and energy homeostasis.

Strengths:

The observations of the authors hint that beyond PA28y association with proteasome, it might also stabilize certain proteins such as C1QBP which influences the energy metabolism.

Weaknesses:

The strength of the work also becomes its main drawback. That is, how PA28y stabilizes C1QBP or how C1QBP elicits its pro-tumourigenic role under PA28y OE.

In most of the …

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

The manuscript the authors have tried to dissect the functions of Proteasome activator 28γ (PA28γ) which is known to activate proteosomal function in an ATP independent manner. Although there are multiple works that have highlighted the role of this protein in tumour, this study specifically tried to develop a correlate with Complement C1q binding protein (C1QBp) that is associated with immune response and energy homeostasis.

Strengths:

The observations of the authors hint that beyond PA28y association with proteasome, it might also stabilize certain proteins such as C1QBP which influences the energy metabolism.

Weaknesses:

The strength of the work also becomes its main drawback. That is, how PA28y stabilizes C1QBP or how C1QBP elicits its pro-tumourigenic role under PA28y OE.

In most of the experiments the authors have been dependent on the parallel changes in the expression of both the proteins to justify their stabilizing interaction. However, this approach is indirect at best and does not confirm the direct stabilizing effect of this interaction. IP experiments do not indicate direct interaction and have some quality issues. The upregulation of C1QBP might be indirect at best. It is quite possible that PA28y might be degrading some secondary protein/complex which is responsible for C1QBP expression. Since the core idea of the work is PA28y direct interaction with C1QBP stabilizing it, the same should be demonstrated in more convincing manner.

In all of the assays C1QBP has been detected as doublet. However, the expression pattern of the two bands vary depending on the experiment. In some cases the upper band is intensely stained and in some the lower bands. Does C1QBP isoforms exist and whether they are differentially regulated depending on experiment conditions/tissue types?

Problems with the background of the work: Line 76. This statement is far-fetched. There are presently a number of literatures that have dealt with metabolic programming of OSCC including identification of specific metabolites. Moreover, beyond estimation of OCR, the authors have not conducted any experiments related to metabolism. In the Introduction, significance of this study and how it will extend our understanding of OSCC needs to be elaborated.

Review of Revised Version:

Although the authors have partly corrected the manuscript by removing the mislabeling in their Co-IP experiments, my primary concern on the actual functional connotations and direct interaction between PA28y and C1QBP still remains unaddressed. As already mentioned in my previous review, since the core idea of the work is PA28y's direct interaction with C1QBP, stabilizing it, the same should be demonstrated in a more convincing manner.

My other observation on the detection of C1QBP as a doublet has been addressed by usage of anti-C1QBP Monoclonal antibody against the polyclonal one used before. C1QBP doublets have not been observed in the present case.

The authors have also worked on the presentation of the background by suitably modifying the statements and incorporating appropriate citations.

However, the authors are requested to follow the recommendations provided to them by the reviewers to address the major concerns.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors tried to determine how PA28g functions in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cells. They hypothesized it may act through metabolic reprogramming in the mitochondria.

Strengths:

They found that the genes of PA28g and C1QBP are in an overlapping interaction network after an analysis of a genome database. They also found that the two proteins interact in coimmunoprecipitation and pull-down assays using the lysate from OSCC cells with or without expression of the exogenous genes. They used truncated C1QBP proteins to map the interaction site to the N-terminal 167 residues of C1QBP protein. They observed the levels of the two proteins are positively correlated in the cells. They provided evidence for the colocalization of the two proteins in the mitochondria and the effect on mitochondrial …

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors tried to determine how PA28g functions in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cells. They hypothesized it may act through metabolic reprogramming in the mitochondria.

Strengths:

They found that the genes of PA28g and C1QBP are in an overlapping interaction network after an analysis of a genome database. They also found that the two proteins interact in coimmunoprecipitation and pull-down assays using the lysate from OSCC cells with or without expression of the exogenous genes. They used truncated C1QBP proteins to map the interaction site to the N-terminal 167 residues of C1QBP protein. They observed the levels of the two proteins are positively correlated in the cells. They provided evidence for the colocalization of the two proteins in the mitochondria and the effect on mitochondrial form and function in vitro and in vivo OSCC models, and the correlation of the protein expression with the prognosis of cancer patients.

Weaknesses:

Many data sets are shown in figures that cannot be understood without more descriptions either in the text or the legend, e.g., Fig. 1A. Similarly, many abbreviations are not defined.

The revision addressed these issues.

Some of the pull-down and coimmunoprecipitation data do not support the conclusion about the PA28g-C1QBP interaction. For example, in Appendix Fig. 1B the Flag-C1QBP was detected in the Myc beads pull-down when the protein was expressed in the 293T cells without the Myc-PA28g, suggesting that the pull-down was not due to the interaction of the C1QBP and PA28g proteins. In Appendix Fig. 1C, assume the SFB stands for a biotin tag, then the SFB-PA28g should be detected in the cells expressing this protein after pull-down by streptavidin; however, it was not. The Western blot data in Fig. 1E and many other figures must be quantified before any conclusions about the levels of proteins can be drawn.

The revision addressed these problems.

The immunoprecipitation method is flawed as it is described. The antigen (PA28g or C1QBP) should bind to the respective antibody that in turn should binds to Protein G beads. The resulting immunocomplex should end up in the pellet fraction after centrifugation, and analyzed further by Western blot for coprecipitates. However, the method in the Appendix states that the supernatant was used for the Western blot.

The revision corrected this method.

To conclude that PA28g stabilizes C1QBP through their physical interaction in the cells, one must show whether a protease inhibitor can substitute PA28q and prevent C1QBP degradation, and also show whether a mutation that disrupt the PA28g-C1QBP interaction can reduce the stability of C1QBP. In Fig. 1F, all cells expressed Myc-PA28g. Therefore, the conclusion that PA28g prevented C1QBP degradation cannot be reached. Instead, since more Myc-PA28g was detected in the cells expressing Flag-C1QBP compared to the cells not expressing this protein, a conclusion would be that the C1QBP stabilized the PA28g. Fig. 1G is a quantification of a Western blot data that should be shown.

The binding site for PA28g in C1QBP was mapped to the N-terminal 167 residues using truncated proteins. One caveat would be that some truncated proteins did not fold correctly in the absence of the sequence that was removed. Thus, the C-terminal region of the C1QBP with residues 168-283 may still bind to the PA29g in the context of full-length protein. In Fig. 1I, more Flag-C1QBP 1-167 was pull-down by Myc-PA28g than the full-length protein or the Flag-C1QBP 1-213. Why?

The interaction site in PA28g for C1QBP was not mapped, which prevents further analysis of the interaction. Also, if the interaction domain can be determined, structural modeling of the complex would be feasible using AlphaFold2 or other programs. Then, it is possible to test point mutations that may disrupt the interaction and if so, the functional effect.

The revision added AlphaFold models for the protein interaction. However, the models were not analyzed and potential mutations that would disrupt the interact were not predicted, made and tested. The revision did not addressed the request for the protease inhibitor.

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

In this manuscript, the authors have tried to dissect the functions of Proteasome activator 28γ (PA28γ) which is known to activate proteasomal function in an ATP-independent manner. Although there are multiple works that have highlighted the role of this protein in tumours, this study specifically tried to develop a correlation with Complement C1q binding protein (C1QBp) that is associated with immune response and energy homeostasis.

Strengths:

The observations of the authors hint that beyond PA28y's association with the proteasome, it might also stabilize certain proteins such as C1QBP which influences energy metabolism.

Weaknesses:

The strength of the work also becomes its main drawback. That is, how …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews.

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

In this manuscript, the authors have tried to dissect the functions of Proteasome activator 28γ (PA28γ) which is known to activate proteasomal function in an ATP-independent manner. Although there are multiple works that have highlighted the role of this protein in tumours, this study specifically tried to develop a correlation with Complement C1q binding protein (C1QBp) that is associated with immune response and energy homeostasis.

Strengths:

The observations of the authors hint that beyond PA28y's association with the proteasome, it might also stabilize certain proteins such as C1QBP which influences energy metabolism.

Weaknesses:

The strength of the work also becomes its main drawback. That is, how PA28y stabilizes C1QBP or how C1QBP elicits its pro-tumourigenic role under PA28y OE.

In most of the experiments, the authors have been dependent on the parallel changes in the expression of both the proteins to justify their stabilizing interaction. However, this approach is indirect at best and does not confirm the direct stabilizing effect of this interaction. IP experiments do not indicate direct interaction and have some quality issues. The upregulation of C1QBP might be indirect at best. It is quite possible that PA28y might be degrading some secondary protein/complex that is responsible for C1QBP expression. Since the core idea of the work is PA28y direct interaction with C1QBP stabilizing it, the same should be demonstrated in a more convincing manner.Thank you very much for the important comments. Using AlphaFold 3, we found that interaction between PA28γ and C1QBP may depend on amino acids 1-167 and 1-213 (Revised Appendix Figure 1D-H), which was confirmed by our immunoprecipitation (Revised Figure 1I). In the future, we will use nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy to analyze protein-protein interaction between PA28γ and C1QBP and demonstrate it by GST pull down in vitro experiments.

In all of the assays, C1QBP has been detected as doublet. However, the expression pattern of the two bands varies depending on the experiment. In some cases, the upper band is intensely stained and in some the lower bands. Do C1QBP isoforms exist and are they differentially regulated depending on experiment conditions/tissue types?

Thank you very much for the important comments. We have rechecked the experimental results with two bands, which may have been caused by using polyclonal antibody of C1QBP (Abcam: ab101267). Therefore, we conducted the experiment with monoclonal antibody of C1QBP (Cell Signaling Technology: #6502) and replaced the corresponding images in revised figure (Revised Figure 1E and Revised Appendix Figure 3D).

Problems with the background of the work: Line 76. This statement is far-fetched. There are presently a number of works of literature that have dealt with the metabolic programming of OSCC including identification of specific metabolites. Moreover, beyond the estimation of OCR, the authors have not conducted any experiments related to metabolism. In the Introduction, the significance of this study and how it will extend our understanding of OSCC needs to be elaborated.

Thank you very much for the important comments. Based on your suggestion, we have revised the content and updated the references (“Introduction”, Paragraph 2, Line 13-17 and Paragraph 4, Line 5-8). In addition, we plan to conduct experiments to investigate the regulation of metabolism by PA28γ and C1QBP and update our data in the future.

The modified content is as follows:

“Current research on metabolic reprogramming in OSCC primarily focused on mechanism of glycolytic metabolism and metabolic shift from glycolysis to oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) of oral squamous cell carcinoma, which lays the groundwork for novel therapeutic interventions to counteract OSCC (Chen et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2020).”

“It is the first study to describe the undiscovered role of PA28γ in promoting the malignant progression of OSCC by elevating mitochondrial function, providing new clinical insights for the treatment of OSCC.”

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors tried to determine how PA28g functions in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cells. They hypothesized it may act through metabolic reprogramming in the mitochondria.

Strengths:

They found that the genes of PA28g and C1QBP are in an overlapping interaction network after an analysis of a genome database. They also found that the two proteins interact in coimmunoprecipitation and pull-down assays using the lysate from OSCC cells with or without expression of the exogenous genes. They used truncated C1QBP proteins to map the interaction site to the N-terminal 167 residues of C1QBP protein. They observed the levels of the two proteins are positively correlated in the cells. They provided evidence for the colocalization of the two proteins in the mitochondria, the effect on mitochondrial form and function in vitro and in vivo OSCC models, and the correlation of the protein expression with the prognosis of cancer patients.

Weaknesses:

Many data sets are shown in figures that cannot be understood without more descriptions, either in the text or the legend, e.g., Figure 1A. Similarly, many abbreviations are not defined.

Thank you very much for the important comments. We have revised the descriptions in the legend to make it easier to understand.

Some of the pull-down and coimmunoprecipitation data do not support the conclusion about the PA28g-C1QBP interaction. For example, in Appendix Figure 1B the Flag-C1QBP was detected in the Myc beads pull-down when the protein was expressed in the 293T cells without the Myc-PA28g, suggesting that the pull-down was not due to the interaction of the C1QBP and PA28g proteins. In Appendix Figure 1C, assume the SFB stands for a biotin tag, then the SFB-PA28g should be detected in the cells expressing this protein after pull-down by streptavidin; however, it was not. The Western blot data in Figure 1E and many other figures must be quantified before any conclusions about the levels of proteins can be drawn.

Thank you very much for the meticulous review. We have rechecked the experimental results, and we made a mistake in the labeling of the image. Therefore, we have corrected it in the revised figure (Revised Appendix Figure 1B, C). In addition, we have conducted a quantitative analysis of gray values to confirm the results of western blot data are accurate by Image J software.

The immunoprecipitation method is flawed as it is described. The antigen (PA28g or C1QBP) should bind to the respective antibody that in turn should binds to Protein G beads. The resulting immunocomplex should end up in the pellet fraction after centrifugation and be analyzed further by Western blot for coprecipitates. However, the method in the Appendix states that the supernatant was used for the Western blot.

Thank you very much for the careful review. We have corrected it in the revised appendix file (“Supplemental Materials and Methods”, Part“Immunoprecipitation assay”, Line 4-6).

The modified content is as follows:

The sample was shaken on a horizontal shaker for 4 h, after which the deposit was collected for western blotting.

To conclude that PA28g stabilizes C1QBP through their physical interaction in the cells, one must show whether a protease inhibitor can substitute PA28q and prevent C1QBP degradation, and show whether a mutation that disrupts the PA28g-C1QBP interaction can reduce the stability of C1QBP. In Figure 1F, all cells expressed Myc-PA28g. Therefore, the conclusion that PA28g prevented C1QBP degradation cannot be reached. Instead, since more Myc-PA28g was detected in the cells expressing Flag-C1QBP compared to the cells not expressing this protein, a conclusion would be that the C1QBP stabilized the PA28g. Figure 1G is a quantification of Western blot data that should be shown.

Thank you very much for the meticulous review. We have rechecked the experimental results, and we made a mistake in the labeling of the image. Therefore, we have corrected it in the revised figure. Compared with the control group, the presence of Myc-PA28γ significantly increased the expression level of Flag-C1QBP (Revised Figure 1F). Gray value analysis showed that in cells transfected with Myc-PA28γ, the decay rate of Flag-C1QBP was significantly slower than that of the control group (Revised Figure 1G), suggesting that PA28γ can delay the protein degradation of C1QBP and stabilize its protein level. This indicates that an increase in the level of PA28γ protein can significantly enhance the expression level of C1QBP protein, while PA28γ can slow down the degradation rate of C1QBP and improve its stability. In addition, we plan to conduct experiments to investigate the effects of protease inhibitors and PA28γ mutants on the stability of C1QBP and update our data in the future.

The binding site for PA28g in C1QBP was mapped to the N-terminal 167 residues using truncated proteins. One caveat would be that some truncated proteins did not fold correctly in the absence of the sequence that was removed. Thus, the C-terminal region of the C1QBP with residues 168-283 may still bind to the PA29g in the context of full-length protein. In Figure 1I, more Flag-C1QBP 1-167 was pulled down by Myc-PA28g than the full-length protein or the Flag-C1QBP 1-213. Why?

Thank you very much for the important comments. Immunoprecipitation is a qualitative experiment. Using AlphaFold 3, we found that interaction between PA28γ and C1QBP may depend on amino acids 1-167 and 1-213 (Revised Appendix Figure 1D-H), which was confirmed by our immunoprecipitation (Revised Figure 1I).

The interaction site in PA28g for C1QBP was not mapped, which prevents further analysis of the interaction. Also, if the interaction domain can be determined, structural modeling of the complex would be feasible using AlphaFold2 or other programs. Then, it is possible to test point mutations that may disrupt the interaction and if so, the functional effect.

Thank you very much for the important comments. Based on your suggestion, we have added relevant content to the revised appendix figure. (Revised Appendix Figure 1D-H).

Recommendations for the authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendations for the authors):

(1) There are a lot of typos in the figure and manuscript that need to be addressed.

Thank you very much for the important comments. We have corrected the typos in the revised figure and manuscript.

(2) Figure 1A: The amount of protein that has been immunoprecipitated is more than the actual amount present in the lysate. The authors should calculate the efficiency of the precipitation to support their results.

Thank you very much for the important comments. Immunoprecipitation is a qualitative experiment. Moreover, it can enrich specific proteins and their binding partners, increase their concentration in the sample, and thus improve the sensitivity of detection.

(3) Figure 1D: The relative expression levels of C1QBP look similar in almost all cell lines except for HN12. It seems that the relation of PA28y with C1QBP is more of a cell type-specific effect. It would be better if the blots were quantified, and the differences were statistically determined.

Thank you very much for the important comments. We have conducted a quantitative analysis of gray values to confirm the results of western blot data are accurate by Image J software.

(4) Figure 1E: How do the authors quantify the expression of the protein in absolute terms? From the methods, it is understood that the flag-tagged construct is stably expressed. Under such conditions, how the authors observed the variable expression of the protein should be elaborated.

Thank you very much for the important comments. We transfected Flag-PA28γ plasmids at 0ug, 0.5ug, 1ug, and 2ug in 293T cells. After collecting the protein for Western Blot, we found that the protein expression of Flag-PA28γ gradually increased. Moreover, the increased protein expression of C1QBP is consistent with the expression of Flag-PA28γ, which indicated a dose-dependent relationship between the two proteins.

(5) Figures 1F, G: The data does not correlate with the arguments presented in the text. The authors propose that interaction with PA28y increases the stability of C1QBP. However, the experiment lacks appropriate controls. Ideally, the expression of C1QBP should be tested in the presence and absence of PA28y. Moreover, the observed difference in expression between lanes 1-4 and 5-8 for myc-PA28y needs to be explained. Are the samples from different sources with variable PA28y expression? Figure 1G quantification for C1QBP does not correlate with the figure presented in F since the expression of the protein in the first four lanes is undetectable.

Thank you very much for the meticulous review. We have rechecked the experimental results, and we made a mistake in the labeling of the image. Therefore, we have corrected it in the revised figure. Compared with the control group, the presence of Myc-PA28γ significantly increased the expression level of Flag-C1QBP (Revised Figure 1F). Gray value analysis showed that in cells transfected with Myc-PA28γ, the decay rate of Flag-C1QBP was significantly slower than that of the control group (Revised Figure 1G), suggesting that PA28γ can delay the protein degradation of C1QBP and stabilize its protein level. This indicates that an increase in the level of PA28γ protein can significantly enhance the expression level of C1QBP protein, while PA28γ can slow down the degradation rate of C1QBP and improve its stability. In addition, we plan to conduct experiments to investigate the effects of protease inhibitors and PA28γ mutants on the stability of C1QBP and update our data in the future.

(6) Appendix Figure 1B: Lane 1 does not express Myc-tagged protein but pull-down has been performed using Myc beads. Then how come flag-C1qbp is getting pulled down in lane 1 if there is no PA28y? This indicates a non-specific interaction of C1qbp with the substrata under the experimental conditions used. Similarly, in Figure 1C SFB-PA28y is expressed in both lanes but is reflected only in lane 2 and not in lane 1 even when pull-down is being performed using SFB beads, again reflecting the non-specificity of the interactions shown through immunoprecipitated.

Thank you very much for the meticulous review. We have rechecked the experimental results, and we made a mistake in the labeling of the image. Therefore, we have corrected it in the revised figure (Revised Appendix Figure 1B, C).

(7) Figure 2A: Figure 2A the co-localization of P28y with C1QBP in mitochondria is not very convincing. The authors are urged to provide high-resolution images for the same along with quantification of co-localization coefficients.

Thank you very much for the important comments. We plan to obtain high-resolution images of co-localization of PA28γ with C1QBP in mitochondria and add the quantification analysis. We will update our data in the future.

(8) Figure 2C: Mitochondria dynamics is an interplay of multiple factors. From the images, it seems that PA28y OE elevates mitochondria biogenesis in general which is having an umbrella effect on mitochondria fusion/fission and OCR. Images also do not convincingly indicate changes in mitochondrial length. The role of PA28y on mitochondria dynamics requires further justification. However, the presented data does not underline whether the changes in mitochondria behaviour are a consequence of PA28y and C1QBP interaction. Correlating higher mitochondria respiration with ROS generation is a far-fetched conclusion since, at present, there are multiple reports that suggest otherwise.

Thank you very much for the important comments. We plan to knock out the interaction regions between PA28γ and C1QBP (like amino acids 1-167 and 1-213) to confirm whether PA28γ affects mitochondrial function through C1QBP and update our data in the future.

(9) Line 157: The presented data does not substantiate the claims made that Pa28y regulates mitochondrial function through C1QBP.

Thank you very much for the important comments. Based on your suggestion, we have made some modifications to make it more accurate (“Results”, Part “PA28γ and C1QBP colocalize in mitochondria and affect mitochondrial functions”, Paragraph 3, Line 1-2).

The modified content is as follows:

“Collectively, these data suggest that PA28γ, which co-localizes with C1QBP in mitochondria, may involve in regulating mitochondrial morphology and function.”

(10) Line 159: From the past data it is not very clear how PA28y upregulates C1QBP, hence the statement is not well supported. The presented data indicates the presence of a functional association between the two proteins.

Thank you very much for the important comments. We detected the expression of C1QBP in two PA28γ-overexpressing OSCC cells (UM1 and 4MOSC2) and found an increase in C1QBP expression (Revised Figure 4B). Based on the results of the protein levels of the mitochondrial respiratory chain complex and other mitochondrial functional proteins, we believe that PA28γ regulates mitochondrial function by upregulating C1QBP.

(11) Figure 4A, B: Given the mitochondrial role of C1QBP, the lesser levels of mitochondrial proteins upon C1QBP silencing are expected. Does it get phenocopied upon PA28y silencing? Similarly, all the subsequent mitochondrial phenotypes in D should be seen in a PA28y-depleted background.

Thank you very much for the important comments. We plan to detect the mitochondrial protein expressions and OCRs of PA28γ-silenced OSCC cells. We will update our data in the future.

(12) Line 198: The presented data do indicate a functional association between these two proteins but it does not provide a solid evidence for the same.

Thank you very much for the important comments. Based on your suggestion, we have made some modifications to make it more accurate (“Discussion”, Paragraph 1, Line 9-10).

The modified content is as follows:

“Excitingly, we found the evidence that PA28γ interacts with and stabilizes C1QBP.”

(13) Line 218-220: In this work, the authors highlight the non-degradome role of PA28y and hence, this fact should be treated appropriately in discussion in line with the presented data.

Thank you very much for the important comments. Based on your suggestion, we have added relevant content to the revised manuscript (“Discussion”, Paragraph 2, Line 16-19).

The modified content is as follows:

“In addition, PA28γ can also play as a non-degradome role on tumor angiogenesis. For example, PA28γ can regulate the activation of NF-κB to promote the secretion of IL-6 and CCL2 in OSCC cells, thus promoting the angiogenesis of endothelial cells ( S. Liu et al., 2018).”

(14) Line 236-240: Although the authors' statement on organ heterogeneity being the cause for getting the contrasting result is justifiable but here there is no direct evidence of PA28y involvement in regulation of OXPHOS and its impact on cellular metabolism (glycolysis, metabolic signalling, etc).

Thank you very much for the important comments. Based on your suggestion, we have made some modifications to make it more accurate (“Discussion”, Paragraph 3, Line 7-9).

The modified content is as follows:

“Therefore, PA28γ's regulation of OXPHOS may impact cellular energy metabolism.”

(15) Line 249: No conclusive data supporting this statement.

Thank you very much for the important comments. Based on your suggestion, we have made some modifications to make it more accurate (“Discussion”, Paragraph 5, Line 1-3).

The modified content is as follows:

“Furthermore, our study reveals that PA28γ can regulate C1QBP and influence mitochondrial morphology and function by enhancing the expression of OPA1, MFN1, MFN2 and the mitochondrial respiratory complex.”

Reviewer #2 (Recommendations for the authors):

(1) The images shown in Figure 2A need to be quantified before the conclusion about the mitochondrial colocalization of the two proteins can be drawn. In Figure 2B and Appendix Figure 2A, the mitochondrial vacuoles and ridge should be indicated for general readers, and quantification should be performed before the conclusion is drawn.

Thank you very much for the important comments. We will update our data in the future.

(2) The OCR data from two cell lines are shown in Figure 2E and F. Which is which? The sentence, "The results indicated ... compared to control cells" in lines 130-132, was confusing; perhaps, it would be clear if "were significantly greater" could be deleted.

Thank you very much for the important comments. We have re-labeled the Figure 2E and F to make it clearly (Revised Figure 2E, F). Based on your suggestion, we have deleted the words in revised manuscript. (“Results”, Part “PA28γ and C1QBP colocalize in mitochondria and affect mitochondrial functions”, Paragraph 1, Line 9-11).

The modified content is as follows:

“The results indicated significantly higher basal respiration, maximal OCRs and ATP production in PA28γ-overexpressing cells compared to control cells (Fig. 2G-I and Appendix Fig. 2B-D).”

(3) Figures 4E-H show the migration, invasive, and proliferation capabilities of the cells. Which for which?

Thank you very much for the important comments. We have re-labeled the Figure 4F-H to make it clearly (Revised Figure 4F-H).

(4) In the Discussion, lines 198-201, it states that "C1QBP enhances ... function of OPA1, MNF1, MFN2..." What is the evidence? In lines 222-224, it says that "the binding sites ... may mask the specific ... modification sites". Please justify. In lines 253-254, "fuse" and fuses" are misleading, Did the authors mean "localize" and "localizes"?

Thank you very much for the important comments. Based on your suggestion, we have made some modifications to make it more accurate (“Discussion”, Paragraph 1, Line 9-13, Paragraph 2, Line 20-23, and Paragraph 5, Line 3-6).

The modified content is as follows:

“Excitingly, we found the evidence that PA28γ interacts with and stabilizes C1QBP. We speculate that aberrantly accumulated C1QBP enhances the function of mitochondrial OXPHOS and leads to the production of additional ATP and ROS by activating the expression and function of OPA1, MNF1, MFN2 and mitochondrial respiratory chain complex proteins.”

“Our study reveals that PA28γ interacts with C1QBP and stabilizes C1QBP at the protein level. Therefore, we speculate that the binding sites of PA28γ and C1QBP may mask the specific post-translational modification sites of C1QBP and inhibit its degradation.”

“Mitochondrial fusion, crucial for oxidative metabolism and cell proliferation, is regulated by MFN1, MFN2, and OPA1. The first two fuse with the outer mitochondrial membrane, while the last fuses with the inner mitochondrial membrane (Westermann, 2010).”

(5) Figure 6 was not referred to in the text. In this figure, PA28g and C1QBP are located in the inner membrane and matrix. Has this been determined? What is the blue ovals that are intermediaries of PA28g/C1QBP and OPA1/MFN1/MFN2?

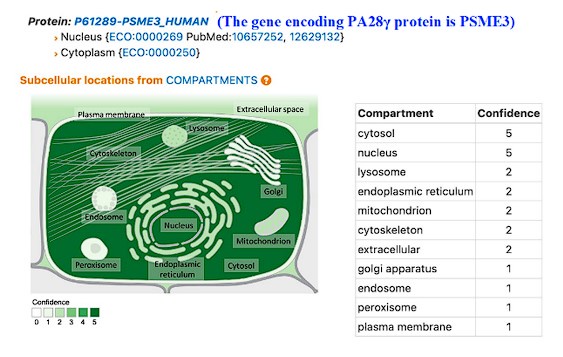

Thank you very much for the important comments. According to our immunofluorescence assay (Figure 2A), PA28γ is in both the nucleus and cytoplasm. A recent study has demonstrated that PA28γ can shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm, participating in various cellular processes. Furthermore, GeneCard information indicates that the subcellular localization of PA28γ includes the nucleus, cytoplasm and mitochondria (Author response image 1). In this article, we mainly focus on the functions of PA28γ and C1QBP located in the cytoplasm. Therefore, figure 6 mainly displays PA28γ and C1QBP in the cytoplasm. Based on your suggestion, we have made some modifications to make it more accurate in revised figure (Revised Figure 6).

Author response image 1.

-

eLife Assessment

This work attempts to demonstrate an ATP-independent non-canonical role of proteasomal component PA28y in the promotion of oral squamous cell carcinoma growth, migration, and invasion. The evidence around the following two areas remains incomplete and would benefit from further experimental work: 1) the stabilisation of the complement C1q binding protein (C1QBp) by PA28y, and 2) the impact of the PA28y-C1QBp interaction on mitochondrial function.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

In this manuscript, the authors have tried to dissect the functions of Proteasome activator 28γ (PA28γ) which is known to activate proteasomal function in an ATP-independent manner. Although there are multiple works that have highlighted the role of this protein in tumours, this study specifically tried to develop a correlation with Complement C1q binding protein (C1QBp) that is associated with immune response and energy homeostasis.

Strengths:

The observations of the authors hint that beyond PA28y's association with the proteasome, it might also stabilize certain proteins such as C1QBP which influences energy metabolism.

Weaknesses:

The strength of the work also becomes its main drawback. That is, how PA28y stabilizes C1QBP or how C1QBP elicits its pro-tumourigenic role under PA28y OE.

In most of …Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

In this manuscript, the authors have tried to dissect the functions of Proteasome activator 28γ (PA28γ) which is known to activate proteasomal function in an ATP-independent manner. Although there are multiple works that have highlighted the role of this protein in tumours, this study specifically tried to develop a correlation with Complement C1q binding protein (C1QBp) that is associated with immune response and energy homeostasis.

Strengths:

The observations of the authors hint that beyond PA28y's association with the proteasome, it might also stabilize certain proteins such as C1QBP which influences energy metabolism.

Weaknesses:

The strength of the work also becomes its main drawback. That is, how PA28y stabilizes C1QBP or how C1QBP elicits its pro-tumourigenic role under PA28y OE.

In most of the experiments, the authors have been dependent on the parallel changes in the expression of both the proteins to justify their stabilizing interaction. However, this approach is indirect at best and does not confirm the direct stabilizing effect of this interaction. IP experiments do not indicate direct interaction and have some quality issues. The upregulation of C1QBP might be indirect at best. It is quite possible that PA28y might be degrading some secondary protein/complex that is responsible for C1QBP expression. Since the core idea of the work is PA28y direct interaction with C1QBP stabilizing it, the same should be demonstrated in a more convincing manner.In all of the assays, C1QBP has been detected as doublet. However, the expression pattern of the two bands varies depending on the experiment. In some cases, the upper band is intensely stained and in some the lower bands. Do C1QBP isoforms exist and are they differentially regulated depending on experiment conditions/tissue types?

Problems with the background of the work: Line 76. This statement is far-fetched. There are presently a number of works of literature that have dealt with the metabolic programming of OSCC including identification of specific metabolites. Moreover, beyond the estimation of OCR, the authors have not conducted any experiments related to metabolism. In the Introduction, the significance of this study and how it will extend our understanding of OSCC needs to be elaborated.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors tried to determine how PA28g functions in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cells. They hypothesized it may act through metabolic reprogramming in the mitochondria.

Strengths:

They found that the genes of PA28g and C1QBP are in an overlapping interaction network after an analysis of a genome database. They also found that the two proteins interact in coimmunoprecipitation and pull-down assays using the lysate from OSCC cells with or without expression of the exogenous genes. They used truncated C1QBP proteins to map the interaction site to the N-terminal 167 residues of C1QBP protein. They observed the levels of the two proteins are positively correlated in the cells. They provided evidence for the colocalization of the two proteins in the mitochondria, the effect on mitochondrial form …

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors tried to determine how PA28g functions in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) cells. They hypothesized it may act through metabolic reprogramming in the mitochondria.

Strengths:

They found that the genes of PA28g and C1QBP are in an overlapping interaction network after an analysis of a genome database. They also found that the two proteins interact in coimmunoprecipitation and pull-down assays using the lysate from OSCC cells with or without expression of the exogenous genes. They used truncated C1QBP proteins to map the interaction site to the N-terminal 167 residues of C1QBP protein. They observed the levels of the two proteins are positively correlated in the cells. They provided evidence for the colocalization of the two proteins in the mitochondria, the effect on mitochondrial form and function in vitro and in vivo OSCC models, and the correlation of the protein expression with the prognosis of cancer patients.

Weaknesses:

Many data sets are shown in figures that cannot be understood without more descriptions, either in the text or the legend, e.g., Figure 1A. Similarly, many abbreviations are not defined.

Some of the pull-down and coimmunoprecipitation data do not support the conclusion about the PA28g-C1QBP interaction. For example, in Appendix Figure 1B the Flag-C1QBP was detected in the Myc beads pull-down when the protein was expressed in the 293T cells without the Myc-PA28g, suggesting that the pull-down was not due to the interaction of the C1QBP and PA28g proteins. In Appendix Figure 1C, assume the SFB stands for a biotin tag, then the SFB-PA28g should be detected in the cells expressing this protein after pull-down by streptavidin; however, it was not. The Western blot data in Figure 1E and many other figures must be quantified before any conclusions about the levels of proteins can be drawn.

The immunoprecipitation method is flawed as it is described. The antigen (PA28g or C1QBP) should bind to the respective antibody that in turn should binds to Protein G beads. The resulting immunocomplex should end up in the pellet fraction after centrifugation and be analyzed further by Western blot for coprecipitates. However, the method in the Appendix states that the supernatant was used for the Western blot.

To conclude that PA28g stabilizes C1QBP through their physical interaction in the cells, one must show whether a protease inhibitor can substitute PA28q and prevent C1QBP degradation, and also show whether a mutation that disrupts the PA28g-C1QBP interaction can reduce the stability of C1QBP. In Figure 1F, all cells expressed Myc-PA28g. Therefore, the conclusion that PA28g prevented C1QBP degradation cannot be reached. Instead, since more Myc-PA28g was detected in the cells expressing Flag-C1QBP compared to the cells not expressing this protein, a conclusion would be that the C1QBP stabilized the PA28g. Figure 1G is a quantification of Western blot data that should be shown.

The binding site for PA28g in C1QBP was mapped to the N-terminal 167 residues using truncated proteins. One caveat would be that some truncated proteins did not fold correctly in the absence of the sequence that was removed. Thus, the C-terminal region of the C1QBP with residues 168-283 may still bind to the PA29g in the context of full-length protein. In Figure 1I, more Flag-C1QBP 1-167 was pulled down by Myc-PA28g than the full-length protein or the Flag-C1QBP 1-213. Why?

The interaction site in PA28g for C1QBP was not mapped, which prevents further analysis of the interaction. Also, if the interaction domain can be determined, structural modeling of the complex would be feasible using AlphaFold2 or other programs. Then, it is possible to test point mutations that may disrupt the interaction and if so, the functional effect

-

-