Comparative proximity biotinylation implicates RAB18 in sterol mobilization and biosynthesis

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

Loss of functional RAB18 causes the autosomal recessive condition Warburg Micro syndrome. To better understand this disease, we used proximity biotinylation to generate an inventory of potential RAB18 effectors. A restricted set of 28 RAB18-interactions were dependent on the binary RAB3GAP1-RAB3GAP2 RAB18-guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) complex. 12 of these 28 interactions are supported by prior reports and we have directly validated novel interactions with SEC22A, TMCO4 and INPP5B. Consistent with a role for RAB18 in regulating membrane contact sites (MCSs), interactors included groups of microtubule/membrane-remodelling proteins, membrane-tethering and docking proteins, and lipid-modifying/transporting proteins. Two of the putative interactors, EBP and OSBPL2/ORP2, have sterol substrates. EBP (emopamil binding protein) is a Δ8-Δ7 sterol isomerase and OSBPL2/ORP2 is a lipid transport protein. This prompted us to investigate a role for RAB18 in cholesterol biosynthesis. We find that the cholesterol precursor and EBP-product lathosterol accumulates in both RAB18-null HeLa cells and RAB3GAP1-null fibroblasts derived from an affected individual. Further, de novo cholesterol biosynthesis is impaired in cells in which RAB18 is absent or dysregulated. Our data demonstrate that GEF-dependent Rab-interactions are highly amenable to interrogation by proximity biotinylation and may suggest that Micro syndrome is a cholesterol biosynthesis disorder.

Article activity feed

-

###Author Response

We thank the reviewers for their comments, which will improve the quality of our manuscript.

Our study describes a novel approach to the identification of GTPase binding-partners. We recapitulated and augmented previous protein-protein interaction data for RAB18 and presented data validating some of our findings. In aggregate, our dataset suggested that RAB18 modulates the establishment of membrane contact sites and the transfer of lipid between closely apposed membranes.

In the original version of our manuscript, we stated that we were exploring the possibility that RAB18 contributes to cholesterol biosynthesis by mobilizing substrates or products of the Δ8-Δ7 sterol isomerase emopamil binding protein (EBP). While our manuscript was under review, we profiled sterols in wild-type and RAB18-null cells and assayed …

###Author Response

We thank the reviewers for their comments, which will improve the quality of our manuscript.

Our study describes a novel approach to the identification of GTPase binding-partners. We recapitulated and augmented previous protein-protein interaction data for RAB18 and presented data validating some of our findings. In aggregate, our dataset suggested that RAB18 modulates the establishment of membrane contact sites and the transfer of lipid between closely apposed membranes.

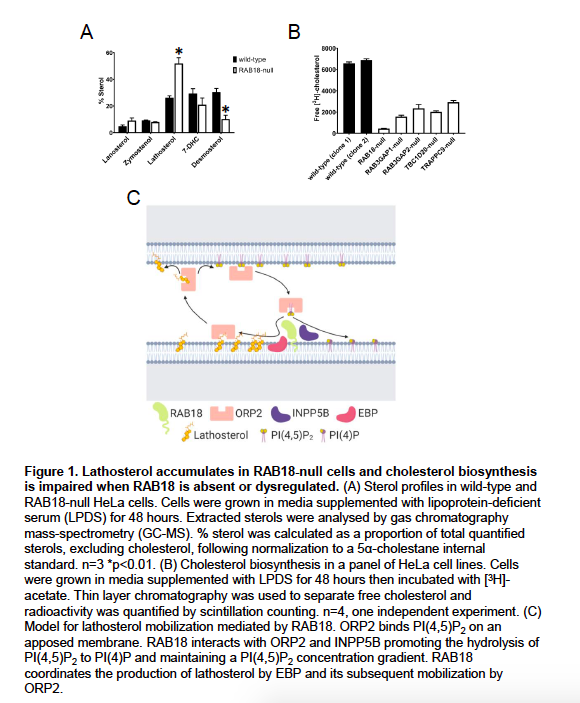

In the original version of our manuscript, we stated that we were exploring the possibility that RAB18 contributes to cholesterol biosynthesis by mobilizing substrates or products of the Δ8-Δ7 sterol isomerase emopamil binding protein (EBP). While our manuscript was under review, we profiled sterols in wild-type and RAB18-null cells and assayed cholesterol biosynthesis in a panel of cell lines (Figure 1).

Our new data show that an EBP-product, lathosterol, accumulates in RAB18-null cells (p<0.01). Levels of a downstream cholesterol intermediate, desmosterol, are reduced in these cells (p<0.01) consistent with impaired delivery of substrates to post-EBP biosynthetic enzymes (Figure 1A). Further, our preliminary data suggests that cholesterol biosynthesis is substantially reduced when RAB18 is absent or dysregulated (4 technical replicates, one independent experiment) (Figure 1B).

Because of the clinical overlap between Micro syndrome and cholesterol biosynthesis disorders including Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome (SLOS; MIM 270400) and lathosterolosis (MIM 607330), our new findings suggest that impaired cholesterol biosynthesis may partly underlie Warburg Micro syndrome pathology. Therapeutic strategies have been developed for the treatment of SLOS and lathosterolosis, and so confirmation of our findings may spur development of similar strategies for Micro syndrome.

Our new findings provide further functional validation of our methodology and support our interpretation of our protein interaction data.

##Response to Reviewer #1 Reply to point 1)

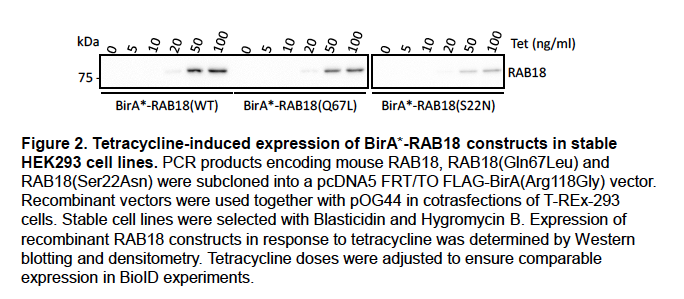

Tetracycline-induced expression of wild-type and mutant BirA*-RAB18 fusion proteins in the stable HEK293 cell lines was quantified by densitometry (Figure 2).

For the HEK293 BioID experiments, tetracycline dosage was adjusted to ensure comparable expression levels. We will include these data in supplemental material in an updated version of our manuscript.

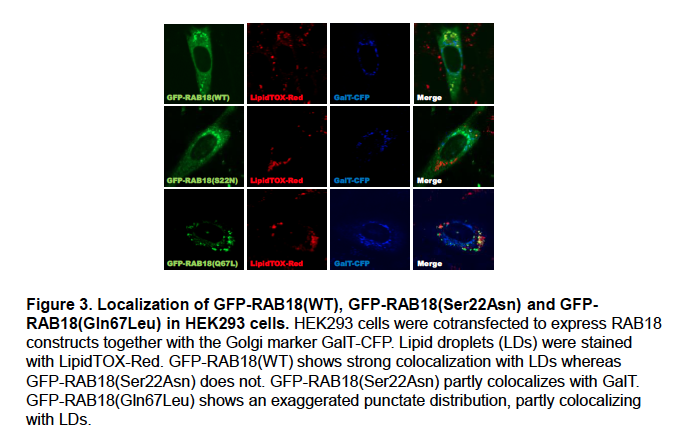

The localization of wild-type and mutant forms of RAB18 in HEK293 cells is somewhat different consistent with previous reports (Ozeki et al. 2005)(Figure 3).

We feel that this may reflect the differential localization of ‘active’ and ‘inactive’ RAB18, with wild-type RAB18 corresponding to a mixture of the two. We will include these data in supplemental material in an updated version of our manuscript.

We acknowledge that the differential localization of wild-type and mutant BirA*-RAB18 might influence the compliment of proteins labeled by these constructs. Nevertheless, we feel that the RAB18(S22N):RAB18(WT) ratios are useful since they distinguish a number of previously-identified RAB18-interactors (manuscript, Figure 1B).

Reply to point 2)

For the HEK293 dataset, spectral counts are provided and for the HeLa dataset LFQ intensities were provided in the manuscript (manuscript, Tables S1 and S2 respectively). However, we did not find that these were useful classifiers for ranking functional interactions when used in isolation.

The extent of labelling produced in a BioID experiment is not wholly determined by the kinetics of protein-protein associations. It is also influenced by, for example, protein abundance, the number and location of exposed surface lysine residues, and protein stability over the timcourse of labelling. We feel that RAB18(S22N):RAB18(WT) and GEF-null:wild-type ratios were helpful in controlling for these factors. Further, that our comparative approach was effective in highlighting known RAB18-interactors and in identifying novel ones.

We acknowledge that our approach may omit some bona fide functional RAB18-interactions, but would argue that our aims were to augment existing functional RAB18-interaction data and avoid false-positives, rather than to emphasise completeness.

Reply to point 3)

We will include representative fluorescence images for the SEC22A, NBAS and ZW10 knockdown experiments in an updated version of our manuscript.

Unfortunately, a suitable antibody for determining knockdown efficiency of SEC22A at the protein level is not commercially available. We will determine SEC22A knockdown efficiency at the mRNA level using qPCR.

Reply to point 4)

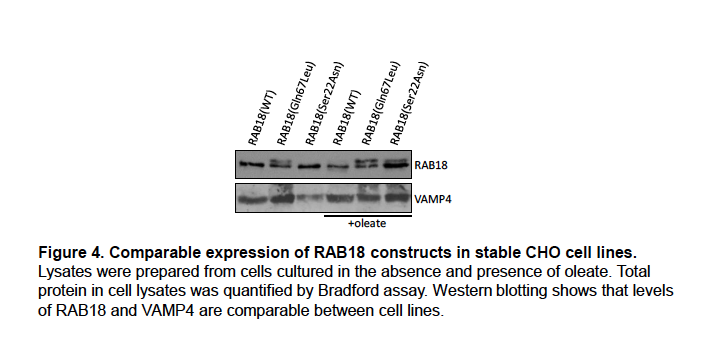

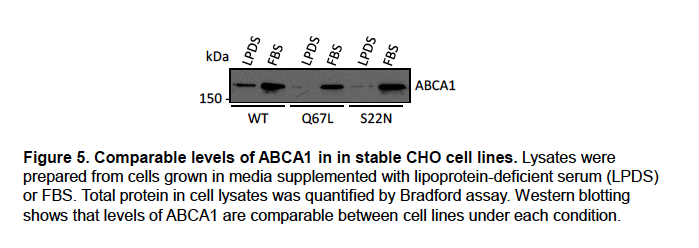

Expression levels of wild-type and mutant RAB18 in the stable CHO cell lines generated for this study were determined by Western blotting and found to be comparable (Figure 4).

We will include these data in supplemental material in an updated version of our manuscript.

The levels of [14C]-CE were higher in RAB18(Gln67Leu) cells than in the other cell lines following loading with [14C]-oleate for 24 hours. We will amend the text to make this explicit. Our interpretation of the data is that ‘active’ RAB18 facilitates the mobilization of cholesterol. When cells are loaded with oleate, this promotes generation and storage of CE. Conversely, when cells are treated with HDL, it promotes more rapid efflux.

Our new data implicating RAB18 in the mobilization of lathosterol supports our interpretation of our loading and efflux experiments. In the light of our new data showing that de novo cholesterol biosynthesis is impaired when RAB18 is absent or dysregulated, it will be interesting to determine whether cholesterol synthesis is increased in the RAB18(Gln67Leu) cells.

##Response to Reviewer #2 Reply to point 1)

We anticipate that the approach of comparative proximity biotinylation in GEF-null and wild-type cell lines will be broadly useful in small GTPase research.

While RAB18 has previously been implicated in regulating membrane contacts, the identification of SEC22A as a RAB18-interactor adds to the previous model for their assembly.

While ORP2 and INPP5B have previously been shown to mediate cholesterol mobilization, the novel finding that they both interact with RAB18 adds to this work. We argue that RAB18-ORP2-INPP5B functions in an analogous manner to ARF1-OSBP-SAC1 in mediating sterol exchange. The broad Rab-binding specificity of multiple OSBP-homologs, and that of multiple phosphoinositide phosphatase enzymes, suggests that this may be a common conserved relationship.

Our new data indicating that RAB18 coordinates generation of sterol intermediates by EBP and their delivery to post-EBP biosynthetic enzymes reveals a new role for Rab proteins in lipid biogenesis. Most importantly, our new findings that RAB18 deficiency is associated with impaired cholesterol biogenesis suggest that Warburg Micro syndrome is a cholesterol biogenesis disorder. Further, that it may be amenable to therapeutic intervention.

Reply to point 2)

Recognising that the effect of RAB18 on cholesterol esterification and efflux could arise from various causes, we previously carried out Western blotting of the CHO cell lines for ABCA1 to determine whether this protein was involved (Figure 5).

Similar levels of ABCA1 expression in these lines suggests it is not. We will include these data in supplemental material in an updated version of our manuscript.

We feel that our new data implicating RAB18 in lathosterol mobilization provides important insight into its role in cholesterol biogenesis. Further, it supports our previous suggestion that RAB18 mediates cholesterol mobilization.

Reply to point 3)

We agree that the established roles for ORP2, TMEM24/C2CD2L and PIP2 at the plasma membrane make this an extremely interesting area for future research; it is one we are actively investigating. However, we respectfully feel that to comprehensively explore the subcellular locations of RAB18-mediated sterol/PIP2 exchange requires another study and is beyond the scope of the present report.

##Response to Reviewer #3 Reply to point 1)

The RAB18-SPG20 interaction has already been validated with a co-immunoprecipitation experiment (Gillingham et al. 2014). We will update the text of our manuscript to make this more explicit, but do not feel it is necessary to recapitulate this work.

We argue in the manuscript that RAB18 may coordinate the assembly of a non-canonical SNARE complex incorporating SEC22A, STX18, BNIP1 and USE1. However, this role may be mediated through prior interaction with the NBAS-RINT1-ZW10 (NRZ) tethering complex and the SM-protein SCFD2 rather than through a direct interaction. We therefore feel that a RAB18-SEC22A interaction may be difficult to validate by conventional means.

The reciprocal experiments with BioID2(Gly40S)-SEC22A did provide tentative confirmation of the interaction together with evidence that a subset of SEC22A-interactions are attenuated when RAB18 is absent or dysregulated. In the light of our new findings reinforcing a role for RAB18 in sterol mobilization at membrane contact sites, it is interesting that one of these is DHRS7, an enzyme with steroids among its putative substrates.

Reply to point 2)

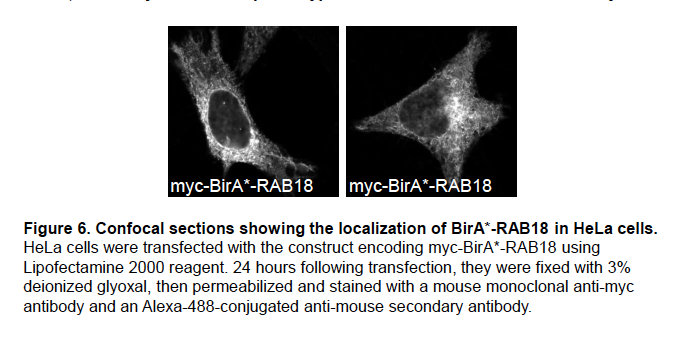

We previously analysed the localization of the BirA*-RAB18 fusion protein in HeLa cells (Figure 6).

It shows a reticular staining pattern consistent with the reported localization of RAB18 to the ER (Gerondopoulos et al. 2014; Ozeki et al. 2005). We will include these data in supplemental material in an updated version of our manuscript.

Heterologous expression of the BirA*-RAB18 fusion protein in HeLa cells identified the interactions between RAB18 and EBP, ORP2 and INPP5B, for which we now have supportive functional evidence. Since the evidence for impaired lathosterol mobilization and cholesterol biosynthesis was derived from experiments on null-cells, in which endogenous protein expression is absent, we feel that rescue experiments are not necessary in the present study. However, such experiments could be highly useful in future studies.

Reply to point 3)

Our screening approach did use both a RAB3GAP-null:wild-type comparison (manuscript, Figure 2, Table S2) and also a RAB18(S22N):RAB18(WT) comparison (manuscript, Figure 1, Table S1). Differences should be expected between these datasets, since they used different cell lines and slightly different methodologies. Nevertheless, proteins identified in both datasets included the known RAB18 effectors NBAS, RINT1, ZW10 and SCFD2, and the novel potential effectors CAMSAP1 and FAM134B.

There is prior evidence for 12 of the 25 RAB3GAP-dependent RAB18 interactions we identified (manuscript, Figure 2D). Among the 6 lipid modifying/mobilizing proteins found exclusively in our HeLa dataset, we previously presented direct evidence for the interaction of RAB18 with TMCO4. We now also have strong functional evidence for its interaction with EBP, ORP2 and INPP5B.

Reply to point 4)

It has been reported that knockdown of SEC22B does not affect the size distribution of lipid droplets (Xu et al. 2018) Figure 8H). Nevertheless, we will carry out qPCR experiments to determine whether the SEC22A siRNAs used in our study affect SEC22B expression. We have found that exogenous expression of SEC22A can cause cellular toxicity. Rescue experiments would therefore be difficult to perform.

Reply to point 5)

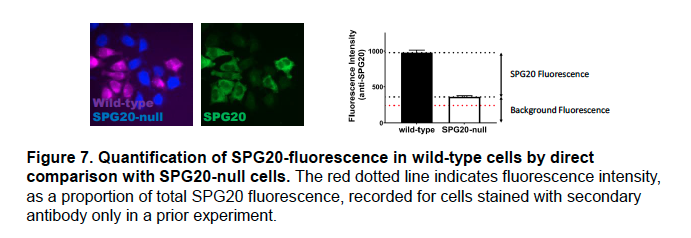

The background fluorescence measured in SPG20-null cells and presented in Figure 4B in the manuscript does not imply that the SPG20 antibody shows significant cross-reactivity. Rather, it reflects the fact that fluorescence intensity is recorded by our Operetta microscope in arbitrary units.

Above (Figure 7), is a version of the panel in which fluorescence from staining cells with only the secondary antibody is included (recorded in a previous experiment and expressed as a proportion of total SPG20 fluorescence in this experiment).

We have found that comparative fluorescence microscopy is more sensitive than immunoblotting. The SPG20 antibody we used to stain the HeLa cells has previously been used in quantitative fluorescence microscopy (Nicholson et al. 2015).

Furthermore, we showed corresponding, significantly reduced, expression of SPG20 in RAB18- and TBC1D20-null RPE1 cells, using quantitative proteomics (manuscript, Table S3).

We acknowledge that quantification of SPG20 transcript levels would clarify the level at which it is downregulated and will carry out qPCR experiments accordingly.

Reply to point 6)

We interpret both the enhanced CE-synthesis following oleate-loading and the rapid efflux upon incubation with HDL (manuscript, Figure 7A) as resulting from increased cholesterol mobilization. Our new data implicating RAB18 in the mobilization of lathosterol support this interpretation.

In the [3H]-cholesterol efflux assay (manuscript, Figure 7B) total [3H]-cholesterol loading at t=0 was 156392±8271 for RAB18(WT) cells, 168425±9103 for RAB18(Gln67Leu) cells and 148867±7609 (cpm determined through scintillation counting). Normalizing to total cellular radioactivity assured that differences in loading between replicates did not skew the results.

The candidate effector likely to directly mediate cholesterol mobilization is ORP2. It has been shown that ORP2 overexpression drives cholesterol to the plasma membrane (Wang et al. 2019). Further, there is evidence for reduced plasma membrane cholesterol in ORP2-null cells (Wang et al. 2019).

We previously carried out Western blotting of the CHO cell lines for ABCA1 to determine whether this protein was involved in altered efflux (Figure 5, above). Similar levels of ABCA1 expression in these lines suggests it is not. We will include these data in supplemental material in an updated version of our manuscript.

References

Gerondopoulos, A., R. N. Bastos, S. Yoshimura, R. Anderson, S. Carpanini, I. Aligianis, M. T. Handley, and F. A. Barr. 2014. 'Rab18 and a Rab18 GEF complex are required for normal ER structure', J Cell Biol, 205: 707-20.

Gillingham, A. K., R. Sinka, I. L. Torres, K. S. Lilley, and S. Munro. 2014. 'Toward a comprehensive map of the effectors of rab GTPases', Dev Cell, 31: 358-73.

Nicholson, J. M., J. C. Macedo, A. J. Mattingly, D. Wangsa, J. Camps, V. Lima, A. M. Gomes, S. Doria, T. Ried, E. Logarinho, and D. Cimini. 2015. 'Chromosome mis-segregation and cytokinesis failure in trisomic human cells', eLife, 4.

Ozeki, S., J. Cheng, K. Tauchi-Sato, N. Hatano, H. Taniguchi, and T. Fujimoto. 2005. 'Rab18 localizes to lipid droplets and induces their close apposition to the endoplasmic reticulum-derived membrane', J Cell Sci, 118: 2601-11.

Wang, H., Q. Ma, Y. Qi, J. Dong, X. Du, J. Rae, J. Wang, W. F. Wu, A. J. Brown, R. G. Parton, J. W. Wu, and H. Yang. 2019. 'ORP2 Delivers Cholesterol to the Plasma Membrane in Exchange for Phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-Bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2)', Mol Cell, 73: 458-73 e7.

Xu, D., Y. Li, L. Wu, Y. Li, D. Zhao, J. Yu, T. Huang, C. Ferguson, R. G. Parton, H. Yang, and P. Li. 2018. 'Rab18 promotes lipid droplet (LD) growth by tethering the ER to LDs through SNARE and NRZ interactions', J Cell Biol, 217: 975-95.

-

###Reviewer #3:

This study by Kiss and colleagues reports the findings of proximity biotinylation experiments for the discovery of novel RAB18 effectors. The authors perform careful proteomic analysis that appears well-controlled and successful in recapitulating known interactions. That small GTPase interactions can be identified with this approach has been previously demonstrated, though the application of this approach to RAB18 is novel and of interest to the field. A number of intriguing findings with potentially important implications are reported. However, this manuscript has several weaknesses.

Major concerns and questions:

As the authors report, proximity biotinylation may not reflect direct protein-protein interactions but simply colocalization of bait and prey proteins. A true protein-protein interaction ideally would be …

###Reviewer #3:

This study by Kiss and colleagues reports the findings of proximity biotinylation experiments for the discovery of novel RAB18 effectors. The authors perform careful proteomic analysis that appears well-controlled and successful in recapitulating known interactions. That small GTPase interactions can be identified with this approach has been previously demonstrated, though the application of this approach to RAB18 is novel and of interest to the field. A number of intriguing findings with potentially important implications are reported. However, this manuscript has several weaknesses.

Major concerns and questions:

As the authors report, proximity biotinylation may not reflect direct protein-protein interactions but simply colocalization of bait and prey proteins. A true protein-protein interaction ideally would be further supported by ancillary experiments such as in vitro binding or co-immunoprecipitation, including an assessment of whether the interaction is affected by the GTP- or GDP-bound state. While co-IP in WT and GEF-deficient cells was performed for 1 candidate interactor (TMC04, Figure 6C), protein-protein interactions were not tested for the other 2, with the latter relying on either repeat BioID (SPG20, Figure 3A) or reciprocal BioID (SEC22A, Figure 5B).

Putative RAB18 interactions may be affected by the BioID fusion itself or by heterologous expression. While it is reassuring that known interactors were detected with this approach, the conclusions would be better supported by testing the localization of the fusion protein in comparison to endogenous RAB18, and/or by rescue of a phenotype associated with RAB18-deficiency.

Conclusions about the dependence of RAB18 interactions on its GTP or GDP-bound state rely on differences observed in cells with deficiency of RAB18 GEFs. It is certainly possible however that RAB3GAP may serve as a GEF for other GTPases, or have other functions, that cause the observed differences in labeling. The conclusions would be strengthened by additional experiments showing a direct effect - e.g. reproducing the disrupted labeling of candidate effectors with a GDP-locked RAB18 point mutant, or showing that RAB3GAP deficiency reduces binding of a candidate effector to RAB18.

The putative role of SEC22A in regulating lipid droplet morphology relies on siRNA perturbations that are prone to off-target effects. This is especially concerning given the high degree of sequence similarity between SEC22A and SEC22B, the latter of which has a known role in regulating LD morphology. Rescue of this phenotype with a siRNA-resistant SEC22A cDNA would rule out this possibility.

The finding of SPG20 protein abundance being affected by RAB18-deficiency relies on immunofluorescence with an antibody exhibiting cross-reactivity. While the authors do attempt to adjust for this non-specific background fluorescence, this conclusion would be strengthened by immunoblotting for a change in abundance of the specific band corresponding to SPG20. If confirmed, measurement of SPG20 transcripts levels would also help clarify the level of regulation for the altered protein abundance.

The influence of stable expression of a RAB18 GTP-locked point mutant on cholesterol metabolism is intriguing but the experimentation appears perfunctory. For 14C-CE cellular levels in 14C-oleate-loaded cells (Figure 7A), the most striking difference is the greatly enhanced synthesis level of CE at t=0. Is the subsequent drop due to an effect of RAB18 on efflux, or simply a consequence of the higher starting level at t=0? For efflux assays on 3H-cholesterol-loaded cells (Figure 7B), the data is only presented as a ratio of 3H activity in media relative to lysates after a 5 hr incubation with HDL. Interpretation of these results would be aided by a more detailed analysis. How does 3H-cholesterol uptake compare after 24 hr incubation but prior to addition of HDL (t=0)? After the 5 hr HDL chase, are the differences in the ratio driven by an increase in extracellular activity, a decrease in intracellular activity, or both? Ultimately these conclusions would be better supported by a more detailed analysis. Does disruption of the candidate effectors phenocopy the effect of RAB18 disruption? Are any known mediators of cholesterol efflux affected by RAB18 disruption? While a comprehensive mechanism may be reasonably considered beyond the scope of this paper, some additional descriptive analysis would be useful in interpreting these findings.

-

###Reviewer #2:

This study used WT and mutant RAB18 to look for interacting proteins in normal and GEF-deficient cells. A catalog of interactions that are regulated by nucleotide binding and/or GEF activity were uncovered. Among identified proteins, there are known/established ones and there are some new ones. Initial validation was carried out for some newly identified effectors such as TMCO4 and Sec22A.

Major concerns and questions:

While the addition of new RAB18 effectors is useful to researchers who are interested in RAB18, the overall conclusion that RAB18 may regulate membrane contacts and lipid metabolism is not new.

Figure 7: the effect of RAB18 on cholesterol esterification and efflux may arise from multiple causes. This set of experiments do not provide any real insights into RAB18's role in cholesterol metabolism.

Given …

###Reviewer #2:

This study used WT and mutant RAB18 to look for interacting proteins in normal and GEF-deficient cells. A catalog of interactions that are regulated by nucleotide binding and/or GEF activity were uncovered. Among identified proteins, there are known/established ones and there are some new ones. Initial validation was carried out for some newly identified effectors such as TMCO4 and Sec22A.

Major concerns and questions:

While the addition of new RAB18 effectors is useful to researchers who are interested in RAB18, the overall conclusion that RAB18 may regulate membrane contacts and lipid metabolism is not new.

Figure 7: the effect of RAB18 on cholesterol esterification and efflux may arise from multiple causes. This set of experiments do not provide any real insights into RAB18's role in cholesterol metabolism.

Given RAB18's interaction with ORP2, TMEM24 and OCRL, perhaps the authors may examine plasma membrane PIP2. The results would be more specific and novel.

-

###Reviewer #1:

This manuscript used proximity biotinylation to discriminate functional RAB18 interactions. The authors provide some evidence for several of the interactors and some functional data supporting a role for RAB18 in modulating cholesterol mobilization.

Major concerns and questions:

Based on the spectral counts, the author calculated a mutant:WT ratios as a readout to identify nucleotide-binding-dependent effectors. But it is important to show that WT protein and mutant protein have similar expression level to begin with. And the intracellular localization of the mutation and WT should also be determined. Do they show the similar intracellular localization?

The ratio of mutation:WT is useful to remove some background. But this may omit some very highly interacting proteins just because their fold change is low. The converse …

###Reviewer #1:

This manuscript used proximity biotinylation to discriminate functional RAB18 interactions. The authors provide some evidence for several of the interactors and some functional data supporting a role for RAB18 in modulating cholesterol mobilization.

Major concerns and questions:

Based on the spectral counts, the author calculated a mutant:WT ratios as a readout to identify nucleotide-binding-dependent effectors. But it is important to show that WT protein and mutant protein have similar expression level to begin with. And the intracellular localization of the mutation and WT should also be determined. Do they show the similar intracellular localization?

The ratio of mutation:WT is useful to remove some background. But this may omit some very highly interacting proteins just because their fold change is low. The converse is true for rare proteins. It would be better to have a list of candidate effectors based on the absolute counts.

Sec22A knockdown will change the morphology of lipid droplets. A knockdown efficiency test and some representative fluorescence images here would make this data more compelling.

Same comment for the cholesterol mobilization experiment. Expression level of the protein is needed. Figure 7A is rather confusing, as the Gln67Leu mutation already has higher CE before loading HDL. Why is this this? Better uptake or reduced efflux? What is the de novo cholesterol synthesis activity in this cell line?

-

##Preprint Review

This preprint was reviewed using eLife’s Preprint Review service, which provides public peer reviews of manuscripts posted on bioRxiv for the benefit of the authors, readers, potential readers, and others interested in our assessment of the work. This review applies only to Version 1 of the preprint: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/871517v1

###Summary: As a possible path to better understand and develop treatments for Warburg Micro Syndrome (WMS), the authors have investigated the networks of protein-protein interactions involving genes mutated in this rare genetic disease. The goals of the work are to identify new proteins involved in the pathophysiology of the disease and to better understand the molecular and cellular effects of disease-causing mutations. The data will likely be of interest to researchers …

##Preprint Review

This preprint was reviewed using eLife’s Preprint Review service, which provides public peer reviews of manuscripts posted on bioRxiv for the benefit of the authors, readers, potential readers, and others interested in our assessment of the work. This review applies only to Version 1 of the preprint: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/871517v1

###Summary: As a possible path to better understand and develop treatments for Warburg Micro Syndrome (WMS), the authors have investigated the networks of protein-protein interactions involving genes mutated in this rare genetic disease. The goals of the work are to identify new proteins involved in the pathophysiology of the disease and to better understand the molecular and cellular effects of disease-causing mutations. The data will likely be of interest to researchers studying WMS and RAB18, the protein focused on here, but reviewers expressed some concerns about the validation and interpretation of the presented protein interaction data.

-