Pleiotropic effects of BAFF on the senescence-associated secretome and growth arrest

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

eLife assessment

Rossi et al. carry out a valuable characterization of the molecular circuitry connecting the immunomodulatory cytokine BAFF (B-cell activating factor) in the context of cellular senescence. They present solid evidence that BAFF is upregulated in response to senescence, and that this upregulation is partially driven by the immune response-regulating transcription factor (TF) IRF1, with potential cell type-specific effects during senescence. Ultimately, these results strongly suggest that BAFF plays a senomorphic role in senescence, modulating downstream senescence-associated phenotypes, and may be an interesting candidate for senomorphic therapy.

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

Senescent cells release a variety of cytokines, proteases, and growth factors collectively known as the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). Sustained SASP contributes to a pattern of chronic inflammation associated with aging and implicated in many age-related diseases. Here, we investigated the expression and function of the immunomodulatory cytokine BAFF (B-cell activating factor; encoded by the TNFSF13B gene), a SASP protein, in multiple senescence models. We first characterized BAFF production across different senescence paradigms, including senescent human diploid fibroblasts (WI-38, IMR-90) and monocytic leukemia cells (THP-1), and tissues of mice induced to undergo senescence. We then identified IRF1 (interferon regulatory factor 1) as a transcription factor required for promoting TNFSF13B mRNA transcription in senescence. We discovered that suppressing BAFF production decreased the senescent phenotype of both fibroblasts and monocyte-like cells, reducing IL6 secretion and SA-β-Gal staining. Importantly, however, the influence of BAFF on the senescence program was cell type-specific: in monocytes, BAFF promoted the early activation of NF-κB and general SASP secretion, while in fibroblasts, BAFF contributed to the production and function of TP53 (p53). We propose that BAFF is elevated across senescence models and is a potential target for senotherapy.

Article activity feed

-

-

Author Response

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

The authors examine the role of secreted BAFF in senescence phenotypes in THP1 AML cells and primary human fibroblasts. In the former, BAFF is found to potentiate the inflammatory phenotype (SASP) and in the latter to potentiate cell cycle arrest. This is an important study because the SASP is still largely considered in generic and monolithic terms, and it is necessary to deconvolute the SASP and examine its many components individually and in different contexts.

Although the results show differences for BAFF in the two cell models, there are many places where key results are missing and the results over-interpreted and/or missing controls.

- Figure 1. Test whether the upregulation of BAFF is specific to senescence, or also in reversible quiescence arrest.

We appreciate the Reviewer’s …

Author Response

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

The authors examine the role of secreted BAFF in senescence phenotypes in THP1 AML cells and primary human fibroblasts. In the former, BAFF is found to potentiate the inflammatory phenotype (SASP) and in the latter to potentiate cell cycle arrest. This is an important study because the SASP is still largely considered in generic and monolithic terms, and it is necessary to deconvolute the SASP and examine its many components individually and in different contexts.

Although the results show differences for BAFF in the two cell models, there are many places where key results are missing and the results over-interpreted and/or missing controls.

- Figure 1. Test whether the upregulation of BAFF is specific to senescence, or also in reversible quiescence arrest.

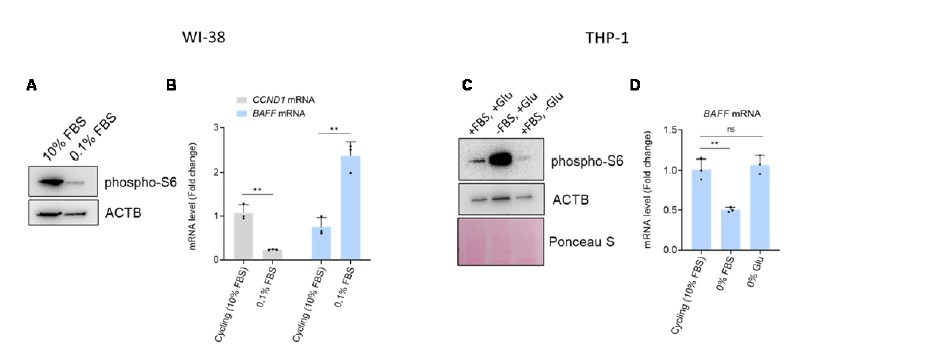

We appreciate the Reviewer’s requests. We performed the experiments in fibroblasts and THP-1 cells to assess BAFF levels in quiescence. As shown below in the figure for Reviewers, we induced quiescence in fibroblasts by serum starvation (0.1%) for 96 h and confirmed the quiescent state by measuring two markers of quiescence (reduction of CCND1 mRNA and reduction of phopho-S6, when compared to cycling cells, following markers established previously (PMID 25483060) (panel A). In this case, the level of BAFF mRNA was increased upon quiescence (panel B).

In THP-1 cells, we tried to induce quiescence by serum starvation and glutamine depletion for 96 h. Unfortunately, however, inducing quiescence in THP-1 cells was rather challenging, likely because they are cancer cells. Thus, we observed a reduction of cell proliferation in both conditions, but we observed a reduction in phospho-S6 only in the samples without glutamine (panel C). We failed to see increased BAFF mRNA levels in quiescent THP-1 cells after either serum starvation or glutamine depletion (panel D).

In summary, further studies will be necessary to fully understand if the increased expression of BAFF seen in senescent cells is also observed in other conditions of growth suppression (such as quiescence or differentiation), as well as whether this effect is specific to different cell types.

- Figure 1, Supplement 1G. Show negative control IgG for immunofluorescence.

We thank the Reviewer for this suggestion. Along with other changes during the revision, we decided to remove the immunofluorescence data in order to include more informative data.

- All results with siRNA should be validated with at least 2 individual siRNAs to eliminate the possibility of off-target effects.

We agree with the Reviewer on the importance of testing individual siRNAs. For BAFF, we originally tested two independent siRNAs (BAFF#1 and BAFF#2) individually, but we also pooled them for additional analysis (and referred to simply as “BAFFsi” along the manuscript). In the revised version of our manuscript, we included the key experiments performed with these two individual BAFF siRNAs. Upon BAFF silencing in THP-1 cells, we observed a reduction of SASP factors and SA-β-Gal activity levels with each individual siRNA (Figure 4-Figure Supplement 1D-F) and with the pooled siRNAs (Figure 4C). For WI-38 cells, we observed a reduction of p53 levels with individual and pooled siRNAs (Figure 7-Figure Supplement 1A), as well as a reduction in IL6 levels and SA-β-Gal activity (Figure 6-Figure Supplement 1D,E). After IRF1 silencing, we observed a reduction in BAFF pre-mRNA with two different pairs of CTRLsi and IRF1si pools (Figure 2I and supplementary Figure 2E). For the data on BAFF receptors, we used SMARTpools from Dharmacon, which are combinations of 4 siRNAs designed by the company to minimize off-target effects. These additions and clarifications are indicated in the revised manuscript.

- To confirm a role for IRF1 in the activation of BAFF, the authors should confirm the binding of IRF1 to the BAFF promoter by ChIP or ChIP-seq.

We thank the Reviewer for this suggestion. We performed ChIP-qPCR analysis in THP-1 cells that were either proliferating or rendered senescent after exposure to IR (Figure 2H, Materials and methods section), and we confirmed the binding of IRF1 to the proximal promoter region of BAFF. As anticipated, this interaction was stronger after inducing senescence.

- Key antibodies should be validated by siRNA knockdown of their targets, for example, TACI, BCMA, and BAFF-R in Figure 5. Note that there is an apparent discrepancy between BCMA data in Figure 5B vs 5C.

We fully agree with the Reviewer on this point and we thank him/her for helping us to improve this part of our manuscript. To address the discrepancy regarding BCMA western blot analysis and flow cytometry data, we silenced BCMA in THP-1 cells and tested two different antibodies advertised to recognize BCMA. This experiment allowed us to identify the correct band for BCMA by western blot analysis. We then confirmed that BCMA is upregulated in senescence, as observed by both western blot and flow cytometry analyses. We have modified the manuscript to reflect these changes. Please find these data in Figure 5A,B and Figure 5-Figure Supplement 1A of the revised manuscript.

- Figure 5E. Negative/specificity controls for this assay should be shown.

We thank the reviewer for this comment and regret that we were unable to provide a negative control. The kit only provides a competitive wild-type oligomer used to test the specificity of the binding. For each sample (CTRLsi, BAFFsi, CTRLsi IR, BAFFsi IR) and each antibody tested (p65, p50, p52, RelB and c-Rel), we evaluated the reductions in signal upon addition of excess competitive oligomer per well (20 pmol/well) compared to wells with an inactive oligomer. However, the negative control was performed only as single replicate, due to the limited quantity of nuclear extracts and the high number of samples and antibodies analyzed. We therefore considered this control as being ‘qualitative’ rather than fully ‘quantitative’.

- Hybridization arrays such as Figure 5H, Figure 6 - Supplement 1I, and Figure 6H should be shown as quantitated, normalized data with statistics from replicates.

We appreciate this request. We have included the quantification and statistics to the phosphoarrays used for THP-1 and WI-38 cells, which had been performed in triplicate (Figure 7A, Figure 5-Figure Supplement 1D). The original arrays are shown in the respective Source Data Files. In the interest of space, we removed the cytokine array performed on IMR-90 cells and left instead the quantitative ELISA for IL6 (Figure 6-Figure Supplement 1F). The data obtained from the cytokine array analysis in Figure 4F and Figure 4-Supplemental Figure 1C are supported by quantitative multiplex ELISA measurements (Figure 4E and Figure 4C).

- Figure 6B - Supplement 1. Controls to confirm fractionation (i.e., non-contamination by cytosolic and nuclear proteins) should be shown.

We thank the Reviewer for this suggestion. We tested the efficiency of fractionation and we did in fact observe some degree of contamination from cytosolic proteins using the earlier version of the kit (Pierce, cat. 89881). We therefore purchased an improved version of the kit (Pierce, cat. A44390) and repeated the surface fractionation assay, which this time showed improved fractionation (Figure 7-Figure Supplement 1B). Interestingly, with the improved fractionation strategy, we observed that BAFF receptors in fibroblasts were almost exclusively localized inside the cell and not on the surface, as we found in THP-1 cells. Further validation of BAFF receptor antibodies has been provided in Figure 5-Figure Supplement 1A. As described in the text, the intracellular localization of BAFF receptors was previously reported in other cell types and conditions (PMID 31137630, PMID 19258594, PMID 30333819, PMID 10903733), and thus it is possible that BAFF may act through non-canonical mechanisms in WI-38 cells. Nonetheless, we did detect a small amount of BAFFR on the cell surface, and furthermore, BAFFR silencing reduced the level of p53 in fibroblasts. Therefore, we propose that BAFFR may be the primary receptor involved in p53 regulation in fibroblasts (Figure 7-Figure Supplement 1B,C). Our data on BAFF receptors deserve deeper characterization in a future study of the functions of BAFF receptors in senescence.

- Figure 6A. Knockdown of BAFF should be shown by western blot.

Yes, definitely. We appreciate this comment and have included BAFF knockdown data in fibroblasts by western blot analysis (Figure 7B).

- Figure 6G. Although BAFF knockdown decreases the expression of p53, p21 increases. How do the authors explain this?

We thank the Reviewer for the interesting question. We too were surprised to observe that the p53-dependent transcripts regulated by BAFF did not include CDKN1A (p21) mRNA, as confirmed by western blot analysis. The accumulation of p21 in senescence can be also regulated by p53-independent pathways and in p53-/- cells, for example by p90RSK, SP1, and ZNF84 (PMID 24136223, PMID 25051367, PMID 33925586). Eventually, we removed the data relative to p21 and γ-H2AX in favor of other data and to streamline the content of this manuscript for the reader.

-

eLife assessment

Rossi et al. carry out a valuable characterization of the molecular circuitry connecting the immunomodulatory cytokine BAFF (B-cell activating factor) in the context of cellular senescence. They present solid evidence that BAFF is upregulated in response to senescence, and that this upregulation is partially driven by the immune response-regulating transcription factor (TF) IRF1, with potential cell type-specific effects during senescence. Ultimately, these results strongly suggest that BAFF plays a senomorphic role in senescence, modulating downstream senescence-associated phenotypes, and may be an interesting candidate for senomorphic therapy.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The authors set out to achieve two overarching objectives: 1) to demonstrate that BAFF is a bona fide senescence-associated factor and 2) to expand the field's understanding of senescence outcomes across cell types and models. By inducing senescence in a multitude of ways and across cell culture and animal models, the authors demonstrate that BAFF is robustly upregulated in response to senescence induction. Beyond mere association, by knocking down, overexpressing, or ectopically adding BAFF, the authors demonstrate that various senescence-associated phenotypes can be altered, suggesting that it is an effector of the senescent state. Moreover, by comparing transcriptomic and proteomic profiles in two very different types of cells-diploid WI-38 human fibroblasts and cancerous THP-1 monocytes-the authors …

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The authors set out to achieve two overarching objectives: 1) to demonstrate that BAFF is a bona fide senescence-associated factor and 2) to expand the field's understanding of senescence outcomes across cell types and models. By inducing senescence in a multitude of ways and across cell culture and animal models, the authors demonstrate that BAFF is robustly upregulated in response to senescence induction. Beyond mere association, by knocking down, overexpressing, or ectopically adding BAFF, the authors demonstrate that various senescence-associated phenotypes can be altered, suggesting that it is an effector of the senescent state. Moreover, by comparing transcriptomic and proteomic profiles in two very different types of cells-diploid WI-38 human fibroblasts and cancerous THP-1 monocytes-the authors identify two parallel trajectories, one involving p53 and one involving NF-kB.

Although trajectory differences may stem from cell type differences, it is possible that the cancerous vs non-cancerous status of the cell lines used may be a more important variable in this case. One question the reader may be left with is: would the two trajectories be different if non-cancerous monocytes with intact p53 were profiled?

Regardless, this study establishes a precedent for characterizing senescence responses in additional cell types of either healthy or diseased origin. Though a number of technical and statistical issues exist in the current version of the manuscript (i.e. use of only a single reference gene for RT-qPCR and inconsistent fold change thresholding in RNA-seq analyses), the results appear robust enough to remain statistically significant after modification. Moreover, many analyses are carried out at both the transcriptomic and proteomic levels with consistent results, highlighting the robustness of their observations.

Ultimately, the results strongly suggest that BAFF plays a senomorphic role in senescence, modulating downstream senescence-associated phenotypes, and may be an interesting candidate for senomorphic therapy.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

The study by Rossi et al. is focused on the role of the SASP factor BAFF as a key regulator of senescent cell biology. Using both in vivo and in vitro studies, the authors show that BAFF, particularly in the monocytic cell line THP-1, is a type I interferon-induced gene. The authors further showed, using both proteomics, transcriptomics, and genetic studies that while BAFF does not play a role in the cell viability or cell cycle arrest of senescent cells, BAFF does regulate other aspects of senescent cell Biology. This includes SA-B-GAL activity and inflammatory gene expression of multiple SASP genes. Lastly, the authors demonstrate that via potential autocrine/paracrine signaling mechanisms BAFF can likely bind to multiple BAFF receptors upregulated in senescent cells, and affect both the p53 and NF-kB …

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

The study by Rossi et al. is focused on the role of the SASP factor BAFF as a key regulator of senescent cell biology. Using both in vivo and in vitro studies, the authors show that BAFF, particularly in the monocytic cell line THP-1, is a type I interferon-induced gene. The authors further showed, using both proteomics, transcriptomics, and genetic studies that while BAFF does not play a role in the cell viability or cell cycle arrest of senescent cells, BAFF does regulate other aspects of senescent cell Biology. This includes SA-B-GAL activity and inflammatory gene expression of multiple SASP genes. Lastly, the authors demonstrate that via potential autocrine/paracrine signaling mechanisms BAFF can likely bind to multiple BAFF receptors upregulated in senescent cells, and affect both the p53 and NF-kB pathways to control inflammatory gene expression.

In summary, we find the manuscript to be both well written and organized, and a nice study on the role of BAFF as a key regulator of senescent cell biology. We believe this finding will be of significant interest to both the senescent cell field and the aging field in general.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

The authors examine the role of secreted BAFF in senescence phenotypes in THP1 AML cells and primary human fibroblasts. In the former, BAFF is found to potentiate the inflammatory phenotype (SASP) and in the latter to potentiate cell cycle arrest. This is an important study because the SASP is still largely considered in generic and monolithic terms, and it is necessary to deconvolute the SASP and examine its many components individually and in different contexts.

Although the results show differences for BAFF in the two cell models, there are many places where key results are missing and the results over-interpreted and/or missing controls.

1. Figure 1. Test whether the upregulation of BAFF is specific to senescence, or also in reversible quiescence arrest.

2. Figure 1, Supplement 1G. Show negative control …

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

The authors examine the role of secreted BAFF in senescence phenotypes in THP1 AML cells and primary human fibroblasts. In the former, BAFF is found to potentiate the inflammatory phenotype (SASP) and in the latter to potentiate cell cycle arrest. This is an important study because the SASP is still largely considered in generic and monolithic terms, and it is necessary to deconvolute the SASP and examine its many components individually and in different contexts.

Although the results show differences for BAFF in the two cell models, there are many places where key results are missing and the results over-interpreted and/or missing controls.

1. Figure 1. Test whether the upregulation of BAFF is specific to senescence, or also in reversible quiescence arrest.

2. Figure 1, Supplement 1G. Show negative control IgG for immunofluorescence.

3. All results with siRNA should be validated with at least 2 individual siRNAs to eliminate the possibility of off-target effects.

4. To confirm a role for IRF1 in the activation of BAFF, the authors should confirm the binding of IRF1 to the BAFF promoter by ChIP or ChIP-seq.

5. Key antibodies should be validated by siRNA knockdown of their targets, for example, TACI, BCMA, and BAFF-R in Figure 5. Note that there is an apparent discrepancy between BCMA data in Figure 5B vs 5C.

6. Figure 5E. Negative/specificity controls for this assay should be shown.

7. Hybridization arrays such as Figure 5H, Figure 6 - Supplement 1I, and Figure 6H should be shown as quantitated, normalized data with statistics from replicates.

8. Figure 6B - Supplement 1. Controls to confirm fractionation (i.e., non-contamination by cytosolic and nuclear proteins) should be shown.

9. Figure 6A. Knockdown of BAFF should be shown by western blot.

10. Figure 6G. Although BAFF knockdown decreases the expression of p53, p21 increases. How do the authors explain this?

-