Experience transforms crossmodal object representations in the anterior temporal lobes

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

eLife assessment

The fMRI study is important because it investigates fundamental questions about the neural basis of multimodal binding using an innovative multi-day learning approach. The results provide solid evidence for learning-related changes in the anterior temporal lobe, however, the interpretation of these changes is not straightforward, and the study does not (yet) provide direct evidence for an integrative code. This paper is of potential interest to a broad audience of neuroscientists.

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

Combining information from multiple senses is essential to object recognition, core to the ability to learn concepts, make new inferences, and generalize across distinct entities. Yet how the mind combines sensory input into coherent crossmodal representations – the crossmodal binding problem – remains poorly understood. Here, we applied multi-echo fMRI across a 4-day paradigm, in which participants learned three-dimensional crossmodal representations created from well-characterized unimodal visual shape and sound features. Our novel paradigm decoupled the learned crossmodal object representations from their baseline unimodal shapes and sounds, thus allowing us to track the emergence of crossmodal object representations as they were learned by healthy adults. Critically, we found that two anterior temporal lobe structures – temporal pole and perirhinal cortex – differentiated learned from non-learned crossmodal objects, even when controlling for the unimodal features that composed those objects. These results provide evidence for integrated crossmodal object representations in the anterior temporal lobes that were different from the representations for the unimodal features. Furthermore, we found that perirhinal cortex representations were by default biased toward visual shape, but this initial visual bias was attenuated by crossmodal learning. Thus, crossmodal learning transformed perirhinal representations such that they were no longer predominantly grounded in the visual modality, which may be a mechanism by which object concepts gain their abstraction.

Article activity feed

-

-

Author Response

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

This study used a multi-day learning paradigm combined with fMRI to reveal neural changes reflecting the learning of new (arbitrary) shape-sound associations. In the scanner, the shapes and sounds are presented separately and together, both before and after learning. When they are presented together, they can be either consistent or inconsistent with the learned associations. The analyses focus on auditory and visual cortices, as well as the object-selective cortex (LOC) and anterior temporal lobe regions (temporal pole (TP) and perirhinal cortex (PRC)). Results revealed several learning-induced changes, particularly in the anterior temporal lobe regions. First, the LOC and PRC showed a reduced bias to shapes vs sounds (presented separately) after learning. Second, the TP responded more …

Author Response

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

This study used a multi-day learning paradigm combined with fMRI to reveal neural changes reflecting the learning of new (arbitrary) shape-sound associations. In the scanner, the shapes and sounds are presented separately and together, both before and after learning. When they are presented together, they can be either consistent or inconsistent with the learned associations. The analyses focus on auditory and visual cortices, as well as the object-selective cortex (LOC) and anterior temporal lobe regions (temporal pole (TP) and perirhinal cortex (PRC)). Results revealed several learning-induced changes, particularly in the anterior temporal lobe regions. First, the LOC and PRC showed a reduced bias to shapes vs sounds (presented separately) after learning. Second, the TP responded more strongly to incongruent than congruent shape-sound pairs after learning. Third, the similarity of TP activity patterns to sounds and shapes (presented separately) was increased for non-matching shape-sound comparisons after learning. Fourth, when comparing the pattern similarity of individual features to combined shape-sound stimuli, the PRC showed a reduced bias towards visual features after learning. Finally, comparing patterns to combined shape-sound stimuli before and after learning revealed a reduced (and negative) similarity for incongruent combinations in PRC. These results are all interpreted as evidence for an explicit integrative code of newly learned multimodal objects, in which the whole is different from the sum of the parts.

The study has many strengths. It addresses a fundamental question that is of broad interest, the learning paradigm is well-designed and controlled, and the stimuli are real 3D stimuli that participants interact with. The manuscript is well written and the figures are very informative, clearly illustrating the analyses performed.

There are also some weaknesses. The sample size (N=17) is small for detecting the subtle effects of learning. Most of the statistical analyses are not corrected for multiple comparisons (ROIs), and the specificity of the key results to specific regions is also not tested. Furthermore, the evidence for an integrative representation is rather indirect, and alternative interpretations for these results are not considered.

We thank the reviewer for their careful reading and the positive comments on our manuscript. As suggested, we have conducted additional analyses of theoretically-motivated ROIs and have found that temporal pole and perirhinal cortex are the only regions to show the key experience-dependent transformations. We are much more cautious with respect to multiple comparisons, and have removed a series of post hoc across-ROI comparisons that were irrelevant to the key questions of the present manuscript. The revised manuscript now includes much more discussion about alternative interpretations as suggested by the reviewer (and also by the other reviewers).

Additionally, we looked into scanning more participants, but our scanner has since had a full upgrade and the sequence used in the current study is no longer supported by our scanner. However, we note that while most analyses contain 17 participants, we employed a within-subject learning design that is not typically used in fMRI experiments and increases our power to detect an effect. This is supported by the robust effect size of the behavioural data, whereby 17 out of 18 participants revealed a learning effect (Cohen’s D = 1.28) and which was replicated in a follow-up experiment with a larger sample size.

We address the other reviewer comments point-by-point in the below.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Li et al. used a four-day fMRI design to investigate how unimodal feature information is combined, integrated, or abstracted to form a multimodal object representation. The experimental question is of great interest and understanding how the human brain combines featural information to form complex representations is relevant for a wide range of researchers in neuroscience, cognitive science, and AI. While most fMRI research on object representations is limited to visual information, the authors examined how visual and auditory information is integrated to form a multimodal object representation. The experimental design is elegant and clever. Three visual shapes and three auditory sounds were used as the unimodal features; the visual shapes were used to create 3D-printed objects. On Day 1, the participants interacted with the 3D objects to learn the visual features, but the objects were not paired with the auditory features, which were played separately. On Day 2, participants were scanned with fMRI while they were exposed to the unimodal visual and auditory features as well as pairs of visual-auditory cues. On Day 3, participants again interacted with the 3D objects but now each was paired with one of the three sounds that played from an internal speaker. On Day 4, participants completed the same fMRI scanning runs they completed on Day 2, except now some visual-auditory feature pairs corresponded with Congruent (learned) objects, and some with Incongruent (unlearned) objects. Using the same fMRI design on Days 2 and 4 enables a well-controlled comparison between feature- and object-evoked neural representations before and after learning. The notable results corresponded to findings in the perirhinal cortex and temporal pole. The authors report (1) that a visual bias on Day 2 for unimodal features in the perirhinal cortex was attenuated after learning on Day 4, (2) a decreased univariate response to congruent vs. incongruent visual-auditory objects in the temporal pole on Day 4, (3) decreased pattern similarity between congruent vs. incongruent pairs of visual and auditory unimodal features in the temporal pole on Day 4, (4) in the perirhinal cortex, visual unimodal features on Day 2 do not correlate with their respective visual-auditory objects on Day 4, and (5) in the perirhinal cortex, multimodal object representations across Days 2 and 4 are uncorrelated for congruent objects and anticorrelated for incongruent. The authors claim that each of these results supports the theory that multimodal objects are represented in an "explicit integrative" code separate from feature representations. While these data are valuable and the results are interesting, the authors' claims are not well supported by their findings.

We thank the reviewer for the careful reading of our manuscript and positive comments. Overall, we now stay closer to the data when describing the results and provide our interpretation of these results in the discussion section while remaining open to alternative interpretations (as also suggested by Reviewer 1).

(1) In the introduction, the authors contrast two theories: (a) multimodal objects are represented in the co-activation of unimodal features, and (b) multimodal objects are represented in an explicit integrative code such that the whole is different than the sum of its parts. However, the distinction between these two theories is not straightforward. An explanation of what is precisely meant by "explicit" and "integrative" would clarify the authors' theoretical stance. Perhaps we can assume that an "explicit" representation is a new representation that is created to represent a multimodal object. What is meant by "integrative" is more ambiguous-unimodal features could be integrated within a representation in a manner that preserves the decodability of the unimodal features, or alternatively the multimodal representation could be completely abstracted away from the constituent features such that the features are no longer decodable. Even if the object representation is "explicit" and distinct from the unimodal feature representations, it can in theory still contain featural information, though perhaps warped or transformed. The authors do not clearly commit to a degree of featural abstraction in their theory of "explicit integrative" multimodal object representations which makes it difficult to assess the validity of their claims.

Due to its ambiguity, we removed the term “explicit” and now make it clear that our central question was whether crossmodal object representations require only unimodal feature-level representations (e.g., frogs are created from only the combination of shape and sound) or whether crossmodal object representations also rely on an integrative code distinct from the unimodal features (e.g., there is something more to “frog” than its original shape and sound). We now clarify this in the revised manuscript.

“One theoretical view from the cognitive sciences suggests that crossmodal objects are built from component unimodal features represented across distributed sensory regions.8 Under this view, when a child thinks about “frog”, the visual cortex represents the appearance of the shape of the frog whereas the auditory cortex represents the croaking sound. Alternatively, other theoretical views predict that multisensory objects are not only built from their component unimodal sensory features, but that there is also a crossmodal integrative code that is different from the sum of these parts.9,10,11,12,13 These latter views propose that anterior temporal lobe structures can act as a polymodal “hub” that combines separate features into integrated wholes.9,11,14,15” – pg. 4

For this reason, we designed our paradigm to equate the unimodal representations, such that neural differences between the congruent and incongruent conditions provide evidence for a crossmodal integrative code different from the unimodal features (because the unimodal features are equated by default in the design).

“Critically, our four-day learning task allowed us to isolate any neural activity associated with integrative coding in anterior temporal lobe structures that emerges with experience and differs from the neural patterns recorded at baseline. The learned and non-learned crossmodal objects were constructed from the same set of three validated shape and sound features, ensuring that factors such as familiarity with the unimodal features, subjective similarity, and feature identity were tightly controlled (Figure 2). If the mind represented crossmodal objects entirely as the reactivation of unimodal shapes and sounds (i.e., objects are constructed from their parts), then there should be no difference between the learned and non-learned objects (because they were created from the same three shapes and sounds). By contrast, if the mind represented crossmodal objects as something over and above their component features (i.e., representations for crossmodal objects rely on integrative coding that is different from the sum of their parts), then there should be behavioral and neural differences between learned and non-learned crossmodal objects (because the only difference across the objects is the learned relationship between the parts). Furthermore, this design allowed us to determine the relationship between the object representation acquired after crossmodal learning and the unimodal feature representations acquired before crossmodal learning. That is, we could examine whether learning led to abstraction of the object representations such that it no longer resembled the unimodal feature representations.” – pg. 5

Furthermore, we agree with the reviewer that our definition and methodological design does not directly capture the structure of the integrative code. With experience, the unimodal feature representations may be completely abstracted away, warped, or changed in a nonlinear transformation. We suggest that crossmodal learning forms an integrative code that is different from the original unimodal representations in the anterior temporal lobes, however, we agree that future work is needed to more directly capture the structure of the integrative code that emerges with experience.

“In our task, participants had to differentiate congruent and incongruent objects constructed from the same three shape and sound features (Figure 2). An efficient way to solve this task would be to form distinct object-level outputs from the overlapping unimodal feature-level inputs such that congruent objects are made to be orthogonal from the representations before learning (i.e., measured as pattern similarity equal to 0 in the perirhinal cortex; Figure 5b, 6, Supplemental Figure S5), whereas non-learned incongruent objects could be made to be dissimilar from the representations before learning (i.e., anticorrelation, measured as patten similarity less than 0 in the perirhinal cortex; Figure 6). Because our paradigm could decouple neural responses to the learned object representations (on Day 4) from the original component unimodal features at baseline (on Day 2), these results could be taken as evidence of pattern separation in the human perirhinal cortex.11,12 However, our pattern of results could also be explained by other types of crossmodal integrative coding. For example, incongruent object representations may be less stable than congruent object representations, such that incongruent objects representation are warped to a greater extent than congruent objects (Figure 6).” – pg. 18

“As one solution to the crossmodal binding problem, we suggest that the temporal pole and perirhinal cortex form unique crossmodal object representations that are different from the distributed features in sensory cortex (Figure 4, 5, 6, Supplemental Figure S5). However, the nature by which the integrative code is structured and formed in the temporal pole and perirhinal cortex following crossmodal experience – such as through transformations, warping, or other factors – is an open question and an important area for future investigation.” – pg. 18

(2) After participants learned the multimodal objects, the authors report a decreased univariate response to congruent visual-auditory objects relative to incongruent objects in the temporal pole. This is claimed to support the existence of an explicit, integrative code for multimodal objects. Given the number of alternative explanations for this finding, this claim seems unwarranted. A simpler interpretation of these results is that the temporal pole is responding to the novelty of the incongruent visual-auditory objects. If there is in fact an explicit, integrative multimodal object representation in the temporal pole, it is unclear why this would manifest in a decreased univariate response.

We thank the reviewer for identifying this issue. Our behavioural design controls unimodal feature-level novelty but allows object-level novelty to differ. Thus, neural differences between the congruent and incongruent conditions reflects sensitivity to the object-level differences between the combination of shape and sound. However, we agree that there are multiple interpretations regarding the nature of how the integrative code is structured in the temporal pole and perirhinal cortex. We have removed the interpretation highlighted by the reviewer from the results. Instead, we now provide our preferred interpretation in the discussion, while acknowledging the other possibilities that the reviewer mentions.

As one possibility, these results in temporal pole may reflect “conceptual combination”. “hummingbird” – a congruent pairing – may require less neural resources than an incongruent pairing such as “bark-frog”.

“Furthermore, these distinct anterior temporal lobe structures may be involved with integrative coding in different ways. For example, the crossmodal object representations measured after learning were found to be related to the component unimodal feature representations measured before learning in the temporal pole but not the perirhinal cortex (Figure 5, 6, Supplemental Figure S5). Moreover, pattern similarity for congruent shape-sound pairs were lower than the pattern similarity for incongruent shape-sound pairs after crossmodal learning in the temporal pole but not the perirhinal cortex (Figure 4b, Supplemental Figure S3a). As one interpretation of this pattern of results, the temporal pole may represent new crossmodal objects by combining previously learned knowledge. 8,9,10,11,13,14,15,33 Specifically, research into conceptual combination has linked the anterior temporal lobes to compound object concepts such as “hummingbird”.34,35,36 For example, participants during our task may have represented the sound-based “humming” concept and visually-based “bird” concept on Day 1, forming the crossmodal “hummingbird” concept on Day 3; Figure 1, 2, which may recruit less activity in temporal pole than an incongruent pairing such as “barking-frog”. For these reasons, the temporal pole may form a crossmodal object code based on pre-existing knowledge, resulting in reduced neural activity (Figure 3d) and pattern similarity towards features associated with learned objects (Figure 4b).”– pg. 18

(3) The authors ran a neural pattern similarity analysis on the unimodal features before and after multimodal object learning. They found that the similarity between visual and auditory features that composed congruent objects decreased in the temporal pole after multimodal object learning. This was interpreted to reflect an explicit integrative code for multimodal objects, though it is not clear why. First, behavioral data show that participants reported increased similarity between the visual and auditory unimodal features within congruent objects after learning, the opposite of what was found in the temporal pole. Second, it is unclear why an analysis of the unimodal features would be interpreted to reflect the nature of the multimodal object representations. Since the same features corresponded with both congruent and incongruent objects, the nature of the feature representations cannot be interpreted to reflect the nature of the object representations per se. Third, using unimodal feature representations to make claims about object representations seems to contradict the theoretical claim that explicit, integrative object representations are distinct from unimodal features. If the learned multimodal object representation exists separately from the unimodal feature representations, there is no reason why the unimodal features themselves would be influenced by the formation of the object representation. Instead, these results seem to more strongly support the theory that multimodal object learning results in a transformation or warping of feature space.

We apologize for the lack of clarity. We have now overhauled this aspect of our manuscript in an attempt to better highlight key aspects of our experimental design. In particular, because the unimodal features composing the congruent and incongruent objects were equated, neural differences between these conditions would provide evidence for an experience-dependent crossmodal integrative code that is different from its component unimodal features.

Related to the second and third points, we were looking at the extent to which the original unimodal representations change with crossmodal learning. Before crossmodal learning, we found that the perirhinal cortex tracked the similarity between the individual visual shape features and the crossmodal objects that were composed of those visual shapes – however, there was no evidence that perirhinal cortex was tracking the unimodal sound features on those crossmodal objects. After crossmodal learning, we see that this visual shape bias in perirhinal cortex was no longer present – that is, the representation in perirhinal cortex started to look less like the visual features that comprise the objects. Thus, crossmodal learning transformed the perirhinal representations so that they were no longer predominantly grounded in a single visual modality, which may be a mechanism by which object concepts gain their abstraction. We have now tried to be clearer about this interpretation throughout the paper.

Notably, we suggest that experience may change both the crossmodal object representations, as well as the unimodal feature representations. For example, we have previously shown that unimodal visual features are influenced by experience in parallel with the representation of the conjunction (e.g., Liang et al., 2020; Cerebral Cortex). Nevertheless, we remain open to the myriad possible structures of the integrative code that might emerge with experience.

We now clarify these points throughout the manuscript. For example:

“We then examined whether the original representations would change after participants learned how the features were paired together to make specific crossmodal objects, conducting the same analysis described above after crossmodal learning had taken place (Figure 5b). With this analysis, we sought to measure the relationship between the representation for the learned crossmodal object and the original baseline representation for the unimodal features. More specifically, the voxel-wise activity for unimodal feature runs before crossmodal learning was correlated to the voxel-wise activity for crossmodal object runs after crossmodal learning (Figure 5b). Another linear mixed model which included modality as a fixed factor within each ROI revealed that the perirhinal cortex was no longer biased towards visual shape after crossmodal learning (F1,32 = 0.12, p = 0.73), whereas the temporal pole, LOC, V1, and A1 remained biased towards either visual shape or sound (F1,30-32 between 16.20 and 73.42, all p < 0.001, η2 between 0.35 and 0.70).” – pg. 14

“To investigate this effect in perirhinal cortex more specifically, we conducted a linear mixed model to directly compare the change in the visual bias of perirhinal representations from before crossmodal learning to after crossmodal learning (green regions in Figure 5a vs. 5b). Specifically, the linear mixed model included learning day (before vs. after crossmodal learning) and modality (visual feature match to crossmodal object vs. sound feature match to crossmodal object). Results revealed a significant interaction between learning day and modality in the perirhinal cortex (F1,775 = 5.56, p = 0.019, η2 = 0.071), meaning that the baseline visual shape bias observed in perirhinal cortex (green region of Figure 5a) was significantly attenuated with experience (green region of Figure 5b). After crossmodal learning, a given shape no longer invoked significant pattern similarity between objects that had the same shape but differed in terms of what they sounded like. Taken together, these results suggest that prior to learning the crossmodal objects, the perirhinal cortex had a default bias toward representing the visual shape information and was not representing sound information of the crossmodal objects. After crossmodal learning, however, the visual shape bias in perirhinal cortex was no longer present. That is, with crossmodal learning, the representations within perirhinal cortex started to look less like the visual features that comprised the crossmodal objects, providing evidence that the perirhinal representations were no longer predominantly grounded in the visual modality.” – pg. 13

“Importantly, the initial visual shape bias observed in the perirhinal cortex was attenuated by experience (Figure 5, Supplemental Figure S5), suggesting that the perirhinal representations had become abstracted and were no longer predominantly grounded in a single modality after crossmodal learning. One possibility may be that the perirhinal cortex is by default visually driven as an extension to the ventral visual stream,10,11,12 but can act as a polymodal “hub” region for additional crossmodal input following learning.” – pg. 19

(4) The most compelling evidence the authors provide for their theoretical claims is the finding that, in the perirhinal cortex, the unimodal feature representations on Day 2 do not correlate with the multimodal objects they comprise on Day 4. This suggests that the learned multimodal object representations are not combinations of their unimodal features. If unimodal features are not decodable within the congruent object representations, this would support the authors' explicit integrative hypothesis. However, the analyses provided do not go all the way in convincing the reader of this claim. First, the analyses reported do not differentiate between congruent and incongruent objects. If this result in the perirhinal cortex reflects the formation of new multimodal object representations, it should only be true for congruent objects but not incongruent objects. Since the analyses combine congruent and incongruent objects it is not possible to know whether this was the case. Second, just because feature representations on Day 2 do not correlate with multimodal object patterns on Day 4 does not mean that the object representations on Day 4 do not contain featural information. This could be directly tested by correlating feature representations on Day 4 with congruent vs. incongruent object representations on Day 4. It could be that representations in the perirhinal cortex are not stable over time and all representations-including unimodal feature representations-shift between sessions, which could explain these results yet not entail the existence of abstracted object representations.

We thank the reviewer for this suggestion and have conducted the two additional analyses. Specifically, we split the congruent and incongruent conditions and also investigated correlations between unimodal representations on Day 4 with crossmodal object representations on Day 4. There was no significant interaction between modality and congruency in any ROI across or within learning days. One possible explanation for these findings is that both congruent and incongruent crossmodal objects are represented differently from their underlying unimodal features, and all of these representations can transform with experience.

However, the new analyses also revealed that perirhinal cortex was the only region without a modality-specific bias after crossmodal learning (e.g., Day 4 Unimodal Feature runs x Day 4 Crossmodal Object runs; now shown in Supplemental Figure S5). Overall, these results are consistent with the notion of a crossmodal integrative code in perirhinal cortex that has changed with experience and is different from the component unimodal features. Nevertheless, we explore alternative interpretations for how the crossmodal code emerges with experience in the discussion.

“To examine whether these results differed by congruency (i.e., whether any modality-specific biases differed as a function of whether the object was congruent or incongruent), we conducted exploratory linear mixed models for each of the five a priori ROIs across learning days. More specifically, we correlated: 1) the voxel-wise activity for Unimodal Feature Runs before crossmodal learning to the voxel-wise activity for Crossmodal Object Runs before crossmodal learning (Day 2 vs. Day 2), 2) the voxel-wise activity for Unimodal Feature Runs before crossmodal learning to the voxel-wise activity for Crossmodal Object Runs after crossmodal learning (Day 2 vs Day 4), and 3) the voxel-wise activity for Unimodal Feature Runs after crossmodal learning to the voxel-wise activity for Crossmodal Object Runs after crossmodal learning (Day 4 vs Day 4). For each of the three analyses described, we then conducted separate linear mixed models which included modality (visual feature match to crossmodal object vs. sound feature match to crossmodal object) and congruency (congruent vs. incongruent)….There was no significant relationship between modality and congruency in any ROI between Day 2 and Day 2 (F1,346-368 between 0.00 and 1.06, p between 0.30 and 0.99), between Day 2 and Day 4 (F1,346-368 between 0.021 and 0.91, p between 0.34 and 0.89), or between Day 4 and Day 4 (F1,346-368 between 0.01 and 3.05, p between 0.082 and 0.93). However, exploratory analyses revealed that perirhinal cortex was the only region without a modality-specific bias and where the unimodal feature runs were not significantly correlated to the crossmodal object runs after crossmodal learning (Supplemental Figure S5).” – pg. 14

“Taken together, the overall pattern of results suggests that representations of the crossmodal objects in perirhinal cortex were heavily influenced by their consistent visual features before crossmodal learning. However, the crossmodal object representations were no longer influenced by the component visual features after crossmodal learning (Figure 5, Supplemental Figure S5). Additional exploratory analyses did not find evidence of experience-dependent changes in the hippocampus or inferior parietal lobes (Supplemental Figure S4c-e).” – pg. 14

“The voxel-wise matrix for Unimodal Feature runs on Day 4 were correlated to the voxel-wise matrix for Crossmodal Object runs on Day 4 (see Figure 5 in the main text for an example). We compared the average pattern similarity (z-transformed Pearson correlation) between shape (blue) and sound (orange) features specifically after crossmodal learning. Consistent with Figure 5b, perirhinal cortex was the only region without a modality-specific bias. Furthermore, perirhinal cortex was the only region where the representations of both the visual and sound features were not significantly correlated to the crossmodal objects. By contrast, every other region maintained a modality-specific bias for either the visual or sound features. These results suggest that perirhinal cortex representations were transformed with experience, such that the initial visual shape representations (Figure 5a) were no longer grounded in a single modality after crossmodal learning. Furthermore, these results suggest that crossmodal learning formed an integrative code different from the unimodal features in perirhinal cortex, as the visual and sound features were not significantly correlated with the crossmodal objects. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Horizontal lines within brain regions indicate a significant main effect of modality. Vertical asterisks denote pattern similarity comparisons relative to 0.” – Supplemental Figure S5

“We found that the temporal pole and perirhinal cortex – two anterior temporal lobe structures – came to represent new crossmodal object concepts with learning, such that the acquired crossmodal object representations were different from the representation of the constituent unimodal features (Figure 5, 6). Intriguingly, the perirhinal cortex was by default biased towards visual shape, but that this initial visual bias was attenuated with experience (Figure 3c, 5, Supplemental Figure S5). Within the perirhinal cortex, the acquired crossmodal object concepts (measured after crossmodal learning) became less similar to their original component unimodal features (measured at baseline before crossmodal learning); Figure 5, 6, Supplemental Figure S5. This is consistent with the idea that object representations in perirhinal cortex integrate the component sensory features into a whole that is different from the sum of the component parts, which might be a mechanism by which object concepts obtain their abstraction…. As one solution to the crossmodal binding problem, we suggest that the temporal pole and perirhinal cortex form unique crossmodal object representations that are different from the distributed features in sensory cortex (Figure 4, 5, 6, Supplemental Figure S5). However, the nature by which the integrative code is structured and formed in the temporal pole and perirhinal cortex following crossmodal experience – such as through transformations, warping, or other factors – is an open question and an important area for future investigation.” – pg. 18

In sum, the authors have collected a fantastic dataset that has the potential to answer questions about the formation of multimodal object representations in the brain. A more precise delineation of different theoretical accounts and additional analyses are needed to provide convincing support for the theory that “explicit integrative” multimodal object representations are formed during learning.

We thank the reviewer for the positive comments and helpful feedback. We hope that our changes to our wording and clarifications to our methodology now more clearly supports the central goal of our study: to find evidence of crossmodal integrative coding different from the original unimodal feature parts in anterior temporal lobe structures. We furthermore agree that future research is needed to delineate the structure of the integrative code that emerges with experience in the anterior temporal lobes.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

This paper uses behavior and functional brain imaging to understand how neural and cognitive representations of visual and auditory stimuli change as participants learn associations among them. Prior work suggests that areas in the anterior temporal (ATL) and perirhinal cortex play an important role in learning/representing cross-modal associations, but the hypothesis has not been directly tested by evaluating behavior and functional imaging before and after learning cross- modal associations. The results show that such learning changes both the perceived similarities amongst stimuli and the neural responses generated within ATL and perirhinal regions, providing novel support for the view that cross-modal learning leads to a representational change in these regions.

This work has several strengths. It tackles an important question for current theories of object representation in the mind and brain in a novel and quite direct fashion, by studying how these representations change with cross-modal learning. As the authors note, little work has directly assessed representational change in ATL following such learning, despite the widespread view that ATL is critical for such representation. Indeed, such direct assessment poses several methodological challenges, which the authors have met with an ingenious experimental design. The experiment allows the authors to maintain tight control over both the familiarity and the perceived similarities amongst the shapes and sounds that comprise their stimuli so that the observed changes across sessions must reflect learned cross-modal associations among these. I especially appreciated the creation of physical objects that participants can explore and the approach to learning in which shapes and sounds are initially experienced independently and later in an associated fashion. In using multi-echo MRI to resolve signals in ventral ATL, the authors have minimized a key challenge facing much work in this area (namely the poor SNR yielded by standard acquisition sequences in ventral ATL). The use of both univariate and multivariate techniques was well-motivated and helpful in testing the central questions. The manuscript is, for the most part, clearly written, and nicely connects the current work to important questions in two literatures, specifically (1) the hypothesized role of the perirhinal cortex in representing/learning complex conjunctions of features and (2) the tension between purely embodied approaches to semantic representation vs the view that ATL regions encode important amodal/crossmodal structure.

There are some places in the manuscript that would benefit from further explanation and methodological detail. I also had some questions about the results themselves and what they signify about the roles of ATL and the perirhinal cortex in object representation.

We thank the reviewer for their positive feedback and address the comments in the below point-by-point responses.

(A) I found the terms "features" and "objects" to be confusing as used throughout the manuscript, and sometimes inconsistent. I think by "features" the authors mean the shape and sound stimuli in their experiment. I think by "object" the authors usually mean the conjunction of a shape with a sound---for instance, when a shape and sound are simultaneously experienced in the scanner, or when the participant presses a button on the shape and hears the sound. The confusion comes partly because shapes are often described as being composed of features, not features in and of themselves. (The same is sometimes true of sounds). So when reading "features" I kept thinking the paper referred to the elements that went together to comprise a shape. It also comes from ambiguous use of the word object, which might refer to (a) the 3D- printed item that people play with, which is an object, or (b) a visually-presented shape (for instance, the localizer involved comparing an "object" to a "phase-scrambled" stimulus---here I assume "object" refers to an intact visual stimulus and not the joint presentation of visual and auditory items). I think the design, stimuli, and results would be easier for a naive reader to follow if the authors used the terms "unimodal representation" to refer to cases where only visual or auditory input is presented, and "cross-modal" or "conjoint" representation when both are present.

We thank the reviewer for this suggestion and agree. We have replaced the terms “features” and “objects” with “unimodal” and “crossmodal” in the title, text, and figures throughout the manuscript for consistency (i.e., “crossmodal binding problem”). To simplify the terminology, we have also removed the localizer results.

(B) There are a few places where I wasn't sure what exactly was done, and where the methods lacked sufficient detail for another scientist to replicate what was done. Specifically:

(1) The behavioral study assessing perceptual similarity between visual and auditory stimuli was unclear. The procedure, stimuli, number of trials, etc, should be explained in sufficient detail in methods to allow replication. The results of the study should also minimally be reported in the supplementary information. Without an understanding of how these studies were carried out, it was very difficult to understand the observed pattern of behavioral change. For instance, I initially thought separate behavioral blocks were carried out for visual versus auditory stimuli, each presented in isolation; however, the effects contrast congruent and incongruent stimuli, which suggests these decisions must have been made for the conjoint presentation of both modalities. I'm still not sure how this worked. Additionally, the manuscript makes a brief mention that similarity judgments were made in the context of "all stimuli," but I didn't understand what that meant. Similarity ratings are hugely sensitive to the contrast set with which items appear, so clarity on these points is pretty important. A strength of the design is the contention that shape and sound stimuli were psychophysically matched, so it is important to show the reader how this was done and what the results were.

We agree and apologize for the lack of sufficient detail in the original manuscript. We now include much more detail about the similarity rating task. The methodology and results of the behavioral rating experiments are now shown in Supplemental Figure S1. In Figure S1a, the similarity ratings are visualized on a multidimensional scaling plot. The triangular geometry for shape (blue) and sound (red) indicate that the subjective similarity was equated within each unimodal feature across individual participants. Quantitatively, there was no difference in similarity between the congruent and incongruent pairings in Figure S1b and Figure S1c prior to crossmodal learning. In addition to providing more information on these methods in the Supplemental Information, we also now provide a more detailed description of the task in the manuscript itself. For convenience, we reproduce these sections below.

“Pairwise Similarity Task. Using the same task as the stimulus validation procedure (Supplemental Figure S1a), participants provided similarity ratings for all combinations of the 3 validated shapes and 3 validated sounds (each of the six features were rated in the context of every other feature in the set, with 4 repeats of the same feature, for a total of 72 trials). More specifically, three stimuli were displayed on each trial, with one at the top and two at the bottom of the screen in the same procedure as we have used previously27. The 3D shapes were visually displayed as a photo, whereas sounds were displayed on screen in a box that could be played over headphones when clicked with the mouse. The participant made an initial judgment by selecting the more similar stimulus on the bottom relative to the stimulus on the top. Afterwards, the participant made a similarity rating between each bottom stimulus with the top stimulus from 0 being no similarity to 5 being identical. This procedure ensured that ratings were made relative to all other stimuli in the set.”– pg. 28

“Pairwise similarity task and results. In the initial stimulus validation experiment, participants provided pairwise ratings for 5 sounds and 3 shapes. The shapes were equated in their subjective similarity that had been selected from a well-characterized perceptually uniform stimulus space27 and the pairwise ratings followed the same procedure as described in ref 27. Based on this initial experiment, we then selected the 3 sounds from the that were most closely equated in their subjective similarity. (a) 3D-printed shapes were displayed as images, whereas sounds were displayed in a box that could be played when clicked by the participant. Ratings were averaged to produce a similarity matrix for each participant, and then averaged to produce a group-level similarity matrix. Shown as triangular representational geometries recovered from multidimensional scaling in the above, shapes (blue) and sounds (orange) were approximately equated in their subjective similarity. These features were then used in the four-day crossmodal learning task. (b) Behavioral results from the four-day crossmodal learning task paired with multi-echo fMRI described in the main text. Before crossmodal learning, there was no difference in similarity between shape and sound features associated with congruent objects compared to incongruent objects – indicating that similarity was controlled at the unimodal feature-level. After crossmodal learning, we observed a robust shift in the magnitude of similarity. The shape and sound features associated with congruent objects were now significantly more similar than the same shape and sound features associated with incongruent objects (p < 0.001), evidence that crossmodal learning changed how participants experienced the unimodal features (observed in 17/18 participants). (c) We replicated this learning-related shift in pattern similarity with a larger sample size (n = 44; observed in 38/44 participants). *** denotes p < 0.001. Horizontal lines denote the comparison of congruent vs. incongruent conditions. – Supplemental Figure S1

(2) The experiences through which participants learned/experienced the shapes and sounds were unclear. The methods mention that they had one minute to explore/palpate each shape and that these experiences were interleaved with other tasks, but it is not clear what the other tasks were, how many such exploration experiences occurred, or how long the total learning time was. The manuscript also mentions that participants learn the shape-sound associations with 100% accuracy but it isn't clear how that was assessed. These details are important partly b/c it seems like very minimal experience to change neural representations in the cortex.

We apologize for the lack of detail and agree with the reviewer’s suggestions – we now include much more information in the methods section. Each behavioral day required about 1 hour of total time to complete, and indeed, participants rapidly learned their associations with minimal experience. For example:

“Behavioral Tasks. On each behavioral day (Day 1 and Day 3; Figure 2), participants completed the following tasks, in this order: Exploration Phase, one Unimodal Feature 1-back run (26 trials), Exploration Phase, one Crossmodal 1-back run (26 trials), Exploration Phase, Pairwise Similarity Task (24 trials), Exploration Phase, Pairwise Similarity Task (24 trials), Exploration Phase, Pairwise Similarity Task (24 trials), and finally, Exploration Phase. To verify learning on Day 3, participants also additionally completed a Learning Verification Task at the end of the session. – pg. 27

“The overall procedure ensured that participants extensively explored the unimodal features on Day 1 and the crossmodal objects on Day 3. The Unimodal Feature and the Crossmodal Object 1-back runs administered on Day 1 and Day 3 served as practice for the neuroimaging sessions on Day 2 and Day 4, during which these 1-back tasks were completed. Each behavioral session required less than 1 hour of total time to complete.” – pg. 27

“Learning Verification Task (Day 3 only). As the final task on Day 3, participants completed a task to ensure that participants successfully formed their crossmodal pairing. All three shapes and sounds were randomly displayed in 6 boxes on a display. Photos of the 3D shapes were shown, and sounds were played by clicking the box with the mouse cursor. The participant was cued with either a shape or sound, and then selected the corresponding paired feature. At the end of Day 3, we found that all participants reached 100% accuracy on this task (10 trials).” – pg. 29

(3) I didn't understand the similarity metric used in the multivariate imaging analyses. The manuscript mentions Z-scored Pearson's r, but I didn't know if this meant (a) many Pearson coefficients were computed and these were then Z-scored, so that 0 indicates a value equal to the mean Pearson correlation and 1 is equal to the standard deviation of the correlations, or (b) whether a Fisher Z transform was applied to each r (so that 0 means r was also around 0). From the interpretation of some results, I think the latter is the approach taken, but in general, it would be helpful to see, in Methods or Supplementary information, exactly how similarity scores were computed, and why that approach was adopted. This is particularly important since it is hard to understand the direction of some key effects.

The reviewer is correct that the Fisher Z transform was applied to each individual r before averaging the correlations. This approach is generally recommended when averaging correlations (see Corey, Dunlap, & Burke, 1998). We are now clearer on this point in the manuscript:

“The z-transformed Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used as the distance metric for all pattern similarity analyses. More specifically, each individual Pearson correlation was Fisher z-transformed and then averaged (see 61).” – pg. 32

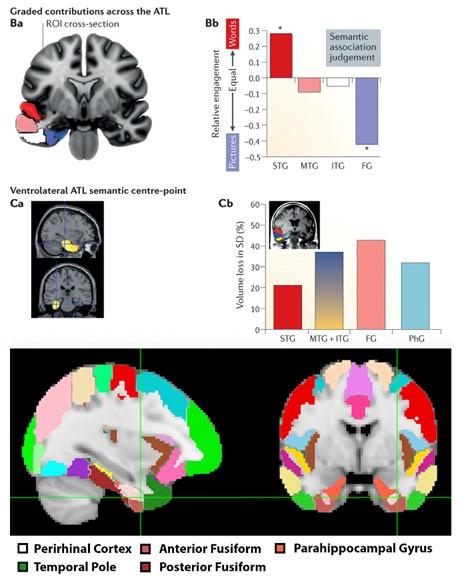

(C) From Figure 3D, the temporal pole mask appears to exclude the anterior fusiform cortex (or the ventral surface of the ATL generally). If so, this is a shame, since that appears to be the locus most important to cross-modal integration in the "hub and spokes" model of semantic representation in the brain. The observation in the paper that the perirhinal cortex seems initially biased toward visual structure while more superior ATL is biased toward auditory structure appears generally consistent with the "graded hub" view expressed, for instance, in our group's 2017 review paper (Lambon Ralph et al., Nature Reviews Neuroscience). The balance of visual- versus auditory-sensitivity in that work appears balanced in the anterior fusiform, just a little lateral to the anterior perirhinal cortex. It would be helpful to know if the same pattern is observed for this area specifically in the current dataset.

We thank the reviewer for this suggestion. After close inspection of Lambon Ralph et al. (2017), we believe that our perirhinal cortex mask appears to be overlapping with the ventral ATL/anterior fusiform region that the reviewer mentions. See Author response image 1 for a visual comparison:

Author response image 1.

The top four figures are sampled from Lambon Ralph et al (2017), whereas the bottom two figures visualize our perirhinal cortex mask (white) and temporal pole mask (dark green) relative to the fusiform cortex. The ROIs visualized were defined from the Harvard-Oxford atlas.

We now mention this area of overlap in our manuscript and link it to the hub and spokes model:

“Notably, our perirhinal cortex mask overlaps with a key region of the ventral anterior temporal lobe thought to be the central locus of crossmodal integration in the “hub and spokes” model of semantic representations.9,50 – pg. 20

(D) While most effects seem robust from the information presented, I'm not so sure about the analysis of the perirhinal cortex shown in Figure 5. This compares (I think) the neural similarity evoked by a unimodal stimulus ("feature") to that evoked by the same stimulus when paired with its congruent stimulus in the other modality ("object"). These similarities show an interaction with modality prior to cross-modal association, but no interaction afterward, leading the authors to suggest that the perirhinal cortex has become less biased toward visual structure following learning. But the plots in Figures 4a and b are shown against different scales on the y-axes, obscuring the fact that all of the similarities are smaller in the after-learning comparison. Since the perirhinal interaction was already the smallest effect in the pre-learning analysis, it isn't really surprising that it drops below significance when all the effects diminish in the second comparison. A more rigorous test would assess the reliability of the interaction of comparison (pre- or post-learning) with modality. The possibility that perirhinal representations become less "visual" following cross-modal learning is potentially important so a post hoc contrast of that kind would be helpful.

We apologize for the lack of clarity. We conducted a linear mixed model to assess the interaction between modality and crossmodal learning day (before and after crossmodal learning) in the perirhinal cortex as described by the reviewer. The critical interaction was significant, which is now clarified in the text as well as in the rescaled figure plots.

“To investigate this effect in perirhinal cortex more specifically, we conducted a linear mixed model to directly compare the change in the visual bias of perirhinal representations from before crossmodal learning to after crossmodal learning (green regions in Figure 5a vs. 5b). Specifically, the linear mixed model included learning day (before vs. after crossmodal learning) and modality (visual feature match to crossmodal object vs. sound feature match to crossmodal object). Results revealed a significant interaction between learning day and modality in the perirhinal cortex (F1,775 = 5.56, p = 0.019, η2 = 0.071), meaning that the baseline visual shape bias observed in perirhinal cortex (green region of Figure 5a) was significantly attenuated with experience (green region of Figure 5b). After crossmodal learning, a given shape no longer invoked significant pattern similarity between objects that had the same shape but differed in terms of what they sounded like. Taken together, these results suggest that prior to learning the crossmodal objects, the perirhinal cortex had a default bias toward representing the visual shape information and was not representing sound information of the crossmodal objects. After crossmodal learning, however, the visual shape bias in perirhinal cortex was no longer present. That is, with crossmodal learning, the representations within perirhinal cortex started to look less like the visual features that comprised the crossmodal objects, providing evidence that the perirhinal representations were no longer predominantly grounded in the visual modality.” – pg. 13

We note that not all effects drop in Figure 5b (even in regions with a similar numerical pattern similarity to PRC, like the hippocampus – also see Supplemental Figure S5 for a comparison for patterns only on Day 4), suggesting that the change in visual bias in PRC is not simply due to noise.

“Importantly, the change in pattern similarity in the perirhinal cortex across learning days (Figure 5) is unlikely to be driven by noise, poor alignment of patterns across sessions, or generally reduced responses. Other regions with numerically similar pattern similarity to perirhinal cortex did not change across learning days (e.g., visual features x crossmodal objects in A1 in Figure 5; the exploratory ROI hippocampus with numerically similar pattern similarity to perirhinal cortex also did not change in Supplemental Figure S4c-d).” – pg. 14

(E) Is there a reason the authors did not look at representation and change in the hippocampus? As a rapid-learning, widely-connected feature-binding mechanism, and given the fairly minimal amount of learning experience, it seems like the hippocampus would be a key area of potential import for the cross-modal association. It also looks as though the hippocampus is implicated in the localizer scan (Figure 3c).

We thank the reviewer for this suggestion and now include additional analyses for the hippocampus. We found no evidence of crossmodal integrative coding different from the unimodal features. Rather, the hippocampus seems to represent the convergence of unimodal features, as evidenced by …[can you give some pithy description for what is meant by “convergence” vs “integration”?]. We provide these results in the Supplemental Information and describe them in the main text:

“Analyses for the hippocampus (HPC) and inferior parietal lobe (IPL). (a) In the visual vs. auditory univariate analysis, there was no visual or sound bias in HPC, but there was a bias towards sounds that increased numerically after crossmodal learning in the IPL. (b) Pattern similarity analyses between unimodal features associated with congruent objects and incongruent objects. Similar to Supplemental Figure S3, there was no main effect of congruency in either region. (c) When we looked at the pattern similarity between Unimodal Feature runs on Day 2 to Crossmodal Object runs on Day 2, we found that there was significant pattern similarity when there was a match between the unimodal feature and the crossmodal object (e.g., pattern similarity > 0). This pattern of results held when (d) correlating the Unimodal Feature runs on Day 2 to Crossmodal Object runs on Day 4, and (e) correlating the Unimodal Feature runs on Day 4 to Crossmodal Object runs on Day 4. Finally, (f) there was no significant pattern similarity between Crossmodal Object runs before learning correlated to Crossmodal Object after learning in HPC, but there was significant pattern similarity in IPL (p < 0.001). Taken together, these results suggest that both HPC and IPL are sensitive to visual and sound content, as the (c, d, e) unimodal feature-level representations were correlated to the crossmodal object representations irrespective of learning day. However, there was no difference between congruent and incongruent pairings in any analysis, suggesting that HPC and IPL did not represent crossmodal objects differently from the component unimodal features. For these reasons, HPC and IPL may represent the convergence of unimodal feature representations (i.e., because HPC and IPL were sensitive to both visual and sound features), but our results do not seem to support these regions in forming crossmodal integrative coding distinct from the unimodal features (i.e., because representations in HPC and IPL did not differentiate the congruent and incongruent conditions and did not change with experience). * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001. Asterisks above or below bars indicate a significant difference from zero. Horizontal lines within brain regions in (a) reflect an interaction between modality and learning day, whereas horizontal lines within brain regions in reflect main effects of (b) learning day, (c-e) modality, or (f) congruency.” – Supplemental Figure S4.

“Notably, our perirhinal cortex mask overlaps with a key region of the ventral anterior temporal lobe thought to be the central locus of crossmodal integration in the “hub and spokes” model of semantic representations.9,50 However, additional work has also linked other brain regions to the convergence of unimodal representations, such as the hippocampus51,52,53 and inferior parietal lobes.54,55 This past work on the hippocampus and inferior parietal lobe does not necessarily address the crossmodal binding problem that was the main focus of our present study, as previous findings often do not differentiate between crossmodal integrative coding and the convergence of unimodal feature representations per se. Furthermore, previous studies in the literature typically do not control for stimulus-based factors such as experience with unimodal features, subjective similarity, or feature identity that may complicate the interpretation of results when determining regions important for crossmodal integration. Indeed, we found evidence consistent with the convergence of unimodal feature-based representations in both the hippocampus and inferior parietal lobes (Supplemental Figure S4), but no evidence of crossmodal integrative coding different from the unimodal features. The hippocampus and inferior parietal lobes were both sensitive to visual and sound features before and after crossmodal learning (see Supplemental Figure S4c-e). Yet the hippocampus and inferior parietal lobes did not differentiate between the congruent and incongruent conditions or change with experience (see Supplemental Figure S4).” – pg. 20

(F) The direction of the neural effects was difficult to track and understand. I think the key observation is that TP and PRh both show changes related to cross-modal congruency - but still it would be helpful if the authors could articulate, perhaps via a schematic illustration, how they think representations in each key area are changing with the cross-modal association. Why does the temporal pole come to activate less for congruent than incongruent stimuli (Figure 3)? And why do TP responses grow less similar to one another for congruent relative to incongruent stimuli after learning (Figure 4)? Why are incongruent stimulus similarities anticorrelated in their perirhinal responses following cross-modal learning (Figure 6)?

We thank the author for identifying this issue, which was also raised by the other reviewers. The reviewer is correct that the key observation is that the TP and PRC both show changes related to crossmodal congruency (given that the unimodal features were equated in the methodological design). However, the structure of the integrative code is less clear, which we now emphasize in the main text. Our findings provide evidence of a crossmodal integrative code that is different from the unimodal features, and future studies are needed to better understand the structure of how such a code might emerge. We now more clearly highlight this distinction throughout the paper:

“By contrast, perirhinal cortex may be involved in pattern separation following crossmodal experience. In our task, participants had to differentiate congruent and incongruent objects constructed from the same three shape and sound features (Figure 2). An efficient way to solve this task would be to form distinct object-level outputs from the overlapping unimodal feature-level inputs such that congruent objects are made to be orthogonal from the representations before learning (i.e., measured as pattern similarity equal to 0 in the perirhinal cortex; Figure 5b, 6, Supplemental Figure S5), whereas non-learned incongruent objects could be made to be dissimilar from the representations before learning (i.e., anticorrelation, measured as patten similarity less than 0 in the perirhinal cortex; Figure 6). Because our paradigm could decouple neural responses to the learned object representations (on Day 4) from the original component unimodal features at baseline (on Day 2), these results could be taken as evidence of pattern separation in the human perirhinal cortex.11,12 However, our pattern of results could also be explained by other types of crossmodal integrative coding. For example, incongruent object representations may be less stable than congruent object representations, such that incongruent objects representation are warped to a greater extent than congruent objects (Figure 6).” – pg. 18

“As one solution to the crossmodal binding problem, we suggest that the temporal pole and perirhinal cortex form unique crossmodal object representations that are different from the distributed features in sensory cortex (Figure 4, 5, 6, Supplemental Figure S5). However, the nature by which the integrative code is structured and formed in the temporal pole and perirhinal cortex following crossmodal experience – such as through transformations, warping, or other factors – is an open question and an important area for future investigation. Furthermore, these anterior temporal lobe structures may be involved with integrative coding in different ways. For example, the crossmodal object representations measured after learning were found to be related to the component unimodal feature representations measured before learning in the temporal pole but not the perirhinal cortex (Figure 5, 6, Supplemental Figure S5). Moreover, pattern similarity for congruent shape-sound pairs were lower than the pattern similarity for incongruent shape-sound pairs after crossmodal learning in the temporal pole but not the perirhinal cortex (Figure 4b, Supplemental Figure S3a). As one interpretation of this pattern of results, the temporal pole may represent new crossmodal objects by combining previously learned knowledge. 8,9,10,11,13,14,15,33 Specifically, research into conceptual combination has linked the anterior temporal lobes to compound object concepts such as “hummingbird”.34,35,36 For example, participants during our task may have represented the sound-based “humming” concept and visually-based “bird” concept on Day 1, forming the crossmodal “hummingbird” concept on Day 3; Figure 1, 2, which may recruit less activity in temporal pole than an incongruent pairing such as “barking-frog”. For these reasons, the temporal pole may form a crossmodal object code based on pre-existing knowledge, resulting in reduced neural activity (Figure 3d) and pattern similarity towards features associated with learned objects (Figure 4b).” – pg. 18

This work represents a key step in our advancing understanding of object representations in the brain. The experimental design provides a useful template for studying neural change related to the cross-modal association that may prove useful to others in the field. Given the broad variety of open questions and potential alternative analyses, an open dataset from this study would also likely be a considerable contribution to the field.

-

eLife assessment

The fMRI study is important because it investigates fundamental questions about the neural basis of multimodal binding using an innovative multi-day learning approach. The results provide solid evidence for learning-related changes in the anterior temporal lobe, however, the interpretation of these changes is not straightforward, and the study does not (yet) provide direct evidence for an integrative code. This paper is of potential interest to a broad audience of neuroscientists.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

This study used a multi-day learning paradigm combined with fMRI to reveal neural changes reflecting the learning of new (arbitrary) shape-sound associations. In the scanner, the shapes and sounds are presented separately and together, both before and after learning. When they are presented together, they can be either consistent or inconsistent with the learned associations. The analyses focus on auditory and visual cortices, as well as the object-selective cortex (LOC) and anterior temporal lobe regions (temporal pole (TP) and perirhinal cortex (PRC)). Results revealed several learning-induced changes, particularly in the anterior temporal lobe regions. First, the LOC and PRC showed a reduced bias to shapes vs sounds (presented separately) after learning. Second, the TP responded more strongly to …

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

This study used a multi-day learning paradigm combined with fMRI to reveal neural changes reflecting the learning of new (arbitrary) shape-sound associations. In the scanner, the shapes and sounds are presented separately and together, both before and after learning. When they are presented together, they can be either consistent or inconsistent with the learned associations. The analyses focus on auditory and visual cortices, as well as the object-selective cortex (LOC) and anterior temporal lobe regions (temporal pole (TP) and perirhinal cortex (PRC)). Results revealed several learning-induced changes, particularly in the anterior temporal lobe regions. First, the LOC and PRC showed a reduced bias to shapes vs sounds (presented separately) after learning. Second, the TP responded more strongly to incongruent than congruent shape-sound pairs after learning. Third, the similarity of TP activity patterns to sounds and shapes (presented separately) was increased for non-matching shape-sound comparisons after learning. Fourth, when comparing the pattern similarity of individual features to combined shape-sound stimuli, the PRC showed a reduced bias towards visual features after learning. Finally, comparing patterns to combined shape-sound stimuli before and after learning revealed a reduced (and negative) similarity for incongruent combinations in PRC. These results are all interpreted as evidence for an explicit integrative code of newly learned multimodal objects, in which the whole is different from the sum of the parts.

The study has many strengths. It addresses a fundamental question that is of broad interest, the learning paradigm is well-designed and controlled, and the stimuli are real 3D stimuli that participants interact with. The manuscript is well written and the figures are very informative, clearly illustrating the analyses performed.

There are also some weaknesses. The sample size (N=17) is small for detecting the subtle effects of learning. Most of the statistical analyses are not corrected for multiple comparisons (ROIs), and the specificity of the key results to specific regions is also not tested. Furthermore, the evidence for an integrative representation is rather indirect, and alternative interpretations for these results are not considered.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Li et al. used a four-day fMRI design to investigate how unimodal feature information is combined, integrated, or abstracted to form a multimodal object representation. The experimental question is of great interest and understanding how the human brain combines featural information to form complex representations is relevant for a wide range of researchers in neuroscience, cognitive science, and AI. While most fMRI research on object representations is limited to visual information, the authors examined how visual and auditory information is integrated to form a multimodal object representation. The experimental design is elegant and clever. Three visual shapes and three auditory sounds were used as the unimodal features; the visual shapes were used to create 3D-printed objects. On Day 1, the participants …

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Li et al. used a four-day fMRI design to investigate how unimodal feature information is combined, integrated, or abstracted to form a multimodal object representation. The experimental question is of great interest and understanding how the human brain combines featural information to form complex representations is relevant for a wide range of researchers in neuroscience, cognitive science, and AI. While most fMRI research on object representations is limited to visual information, the authors examined how visual and auditory information is integrated to form a multimodal object representation. The experimental design is elegant and clever. Three visual shapes and three auditory sounds were used as the unimodal features; the visual shapes were used to create 3D-printed objects. On Day 1, the participants interacted with the 3D objects to learn the visual features, but the objects were not paired with the auditory features, which were played separately. On Day 2, participants were scanned with fMRI while they were exposed to the unimodal visual and auditory features as well as pairs of visual-auditory cues. On Day 3, participants again interacted with the 3D objects but now each was paired with one of the three sounds that played from an internal speaker. On Day 4, participants completed the same fMRI scanning runs they completed on Day 2, except now some visual-auditory feature pairs corresponded with Congruent (learned) objects, and some with Incongruent (unlearned) objects. Using the same fMRI design on Days 2 and 4 enables a well-controlled comparison between feature- and object-evoked neural representations before and after learning. The notable results corresponded to findings in the perirhinal cortex and temporal pole. The authors report (1) that a visual bias on Day 2 for unimodal features in the perirhinal cortex was attenuated after learning on Day 4, (2) a decreased univariate response to congruent vs. incongruent visual-auditory objects in the temporal pole on Day 4, (3) decreased pattern similarity between congruent vs. incongruent pairs of visual and auditory unimodal features in the temporal pole on Day 4, (4) in the perirhinal cortex, visual unimodal features on Day 2 do not correlate with their respective visual-auditory objects on Day 4, and (5) in the perirhinal cortex, multimodal object representations across Days 2 and 4 are uncorrelated for congruent objects and anticorrelated for incongruent. The authors claim that each of these results supports the theory that multimodal objects are represented in an "explicit integrative" code separate from feature representations. While these data are valuable and the results are interesting, the authors' claims are not well supported by their findings.

(1) In the introduction, the authors contrast two theories: (a) multimodal objects are represented in the co-activation of unimodal features, and (b) multimodal objects are represented in an explicit integrative code such that the whole is different than the sum of its parts. However, the distinction between these two theories is not straightforward. An explanation of what is precisely meant by "explicit" and "integrative" would clarify the authors' theoretical stance. Perhaps we can assume that an "explicit" representation is a new representation that is created to represent a multimodal object. What is meant by "integrative" is more ambiguous-unimodal features could be integrated within a representation in a manner that preserves the decodability of the unimodal features, or alternatively the multimodal representation could be completely abstracted away from the constituent features such that the features are no longer decodable. Even if the object representation is "explicit" and distinct from the unimodal feature representations, it can in theory still contain featural information, though perhaps warped or transformed. The authors do not clearly commit to a degree of featural abstraction in their theory of "explicit integrative" multimodal object representations which makes it difficult to assess the validity of their claims.

(2) After participants learned the multimodal objects, the authors report a decreased univariate response to congruent visual-auditory objects relative to incongruent objects in the temporal pole. This is claimed to support the existence of an explicit, integrative code for multimodal objects. Given the number of alternative explanations for this finding, this claim seems unwarranted. A simpler interpretation of these results is that the temporal pole is responding to the novelty of the incongruent visual-auditory objects. If there is in fact an explicit, integrative multimodal object representation in the temporal pole, it is unclear why this would manifest in a decreased univariate response.

(3) The authors ran a neural pattern similarity analysis on the unimodal features before and after multimodal object learning. They found that the similarity between visual and auditory features that composed congruent objects decreased in the temporal pole after multimodal object learning. This was interpreted to reflect an explicit integrative code for multimodal objects, though it is not clear why. First, behavioral data show that participants reported increased similarity between the visual and auditory unimodal features within congruent objects after learning, the opposite of what was found in the temporal pole. Second, it is unclear why an analysis of the unimodal features would be interpreted to reflect the nature of the multimodal object representations. Since the same features corresponded with both congruent and incongruent objects, the nature of the feature representations cannot be interpreted to reflect the nature of the object representations per se. Third, using unimodal feature representations to make claims about object representations seems to contradict the theoretical claim that explicit, integrative object representations are distinct from unimodal features. If the learned multimodal object representation exists separately from the unimodal feature representations, there is no reason why the unimodal features themselves would be influenced by the formation of the object representation. Instead, these results seem to more strongly support the theory that multimodal object learning results in a transformation or warping of feature space.

(4) The most compelling evidence the authors provide for their theoretical claims is the finding that, in the perirhinal cortex, the unimodal feature representations on Day 2 do not correlate with the multimodal objects they comprise on Day 4. This suggests that the learned multimodal object representations are not combinations of their unimodal features. If unimodal features are not decodable within the congruent object representations, this would support the authors' explicit integrative hypothesis. However, the analyses provided do not go all the way in convincing the reader of this claim. First, the analyses reported do not differentiate between congruent and incongruent objects. If this result in the perirhinal cortex reflects the formation of new multimodal object representations, it should only be true for congruent objects but not incongruent objects. Since the analyses combine congruent and incongruent objects it is not possible to know whether this was the case. Second, just because feature representations on Day 2 do not correlate with multimodal object patterns on Day 4 does not mean that the object representations on Day 4 do not contain featural information. This could be directly tested by correlating feature representations on Day 4 with congruent vs. incongruent object representations on Day 4. It could be that representations in the perirhinal cortex are not stable over time and all representations-including unimodal feature representations-shift between sessions, which could explain these results yet not entail the existence of abstracted object representations.

In sum, the authors have collected a fantastic dataset that has the potential to answer questions about the formation of multimodal object representations in the brain. A more precise delineation of different theoretical accounts and additional analyses are needed to provide convincing support for the theory that "explicit integrative" multimodal object representations are formed during learning.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):