The effect of calcium supplementation in people under 35 years old: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

Evaluation Summary:

This is a systematic review by meta-analysis about the effect of calcium supplementation on bone health in people under 35 years old. The authors found that calcium supplementation can significantly improve BMD and BMC in young people. Moreover, a better effect of calcium supplementation was shown in people who are at the plateau of their PBM. A unique feature of this study is that it focused on people at the age before achieving PBM or age at the plateau of PBM, which is different from previous studies that mainly focused on the elderly or children.

(This preprint has been reviewed by eLife. We include the public reviews from the reviewers here; the authors also receive private feedback with suggested changes to the manuscript. The reviewers remained anonymous to the authors.)

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

The effect of calcium supplementation on bone mineral accretion in people under 35 years old is inconclusive. To comprehensively summarize the evidence for the effect of calcium supplementation on bone mineral accretion in young populations (≤35 years).

Methods:

This is a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Pubmed, Embase, ProQuest, CENTRAL, WHO Global Index Medicus, Clinical Trials.gov, WHO ICTRP, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), and Wanfang Data databases were systematically searched from database inception to April 25, 2021. Randomized clinical trials assessing the effects of calcium supplementation on bone mineral density (BMD) or bone mineral content (BMC) in people under 35 years old.

Results:

This systematic review and meta-analysis identified 43 studies involving 7,382 subjects. Moderate certainty of evidence showed that calcium supplementation was associated with the accretion of BMD and BMC, especially on femoral neck (standardized mean difference [SMD] 0.627, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.338–0.915; SMD 0.364, 95% CI 0.134–0.595; respectively) and total body (SMD 0.330, 95% CI 0.163–0.496; SMD 0.149, 95% CI 0.006–0.291), also with a slight improvement effect on lumbar spine BMC (SMD 0.163, 95% CI 0.008–0.317), no effects on total hip BMD and BMC and lumbar spine BMD were observed. Very interestingly, subgroup analyses suggested that the improvement of bone at femoral neck was more pronounced in the peripeak bone mass (PBM) population (20–35 years) than the pre-PBM population (<20 years).

Conclusions:

Our findings provided novel insights and evidence in calcium supplementation, which showed that calcium supplementation significantly improves bone mass, implying that preventive calcium supplementation before or around achieving PBM may be a shift in the window of intervention for osteoporosis.

Funding:

This work was supported by Wenzhou Medical University grant [89219029].

Article activity feed

-

-

Author Response

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Although a bunch of studies have been carried out to see whether calcium supplementation is a prerequisite for the promotion of bone health or prevention of bone diseases, this is the first trial to see its effect on the population whose age is reaching peak bone mass. Outcomes are clear and justified by sound methodology. Also, the message from this systematic review could directly influence the clinical decision on who might gain benefit from calcium supplementation.

We are very grateful for your considerate comments and your recognition of our work in this study. Your suggestions really helped us to improve the clarity of this manuscript.

Strengths of this study are:

- This is the first systematic review by meta-analysis to focus on people at the age before achieving peak bone mass …

Author Response

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Although a bunch of studies have been carried out to see whether calcium supplementation is a prerequisite for the promotion of bone health or prevention of bone diseases, this is the first trial to see its effect on the population whose age is reaching peak bone mass. Outcomes are clear and justified by sound methodology. Also, the message from this systematic review could directly influence the clinical decision on who might gain benefit from calcium supplementation.

We are very grateful for your considerate comments and your recognition of our work in this study. Your suggestions really helped us to improve the clarity of this manuscript.

Strengths of this study are:

- This is the first systematic review by meta-analysis to focus on people at the age before achieving peak bone mass (PBM) and at the age around the PBM. 2) Detailed subgroup and sensitivity analyses drew consistent and clear results.

Thank you very much for your comments. We are very grateful for your recognition of our work in this study.

Limitations of this study are:

- Substantial intertrial heterogeneity should be considered in terms of dose effect of calcium supplementation and differences between both sexes etc.

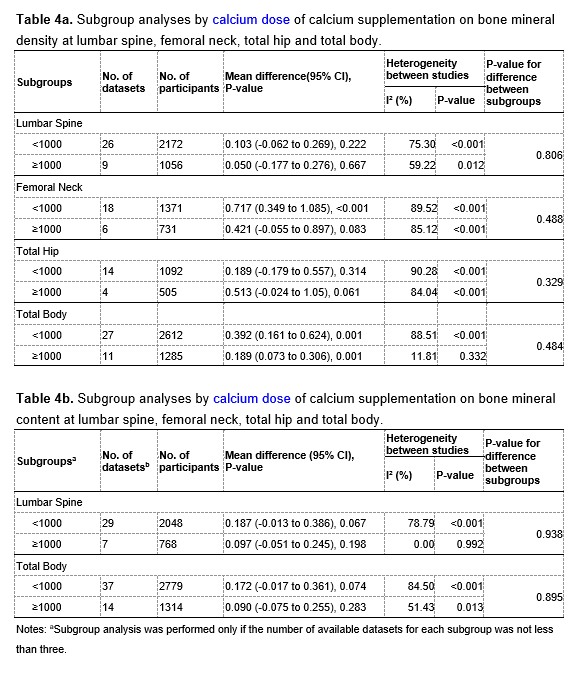

Thank you very much for your kind comments. We performed subgroup analyses to explore whether different doses of calcium supplementation had different effects, and the results are showed in Table 4a and 4b at the end of this Author Response. The results showed that the intertrial heterogeneity in the subgroup with doses of calcium supplementation greater than or equal to 1000 mg/day was significantly smaller than that in the subgroup with doses less than 1000 mg/day, suggesting that different doses of calcium supplementation across trials may be a potential source of the substantial intertrial heterogeneity.

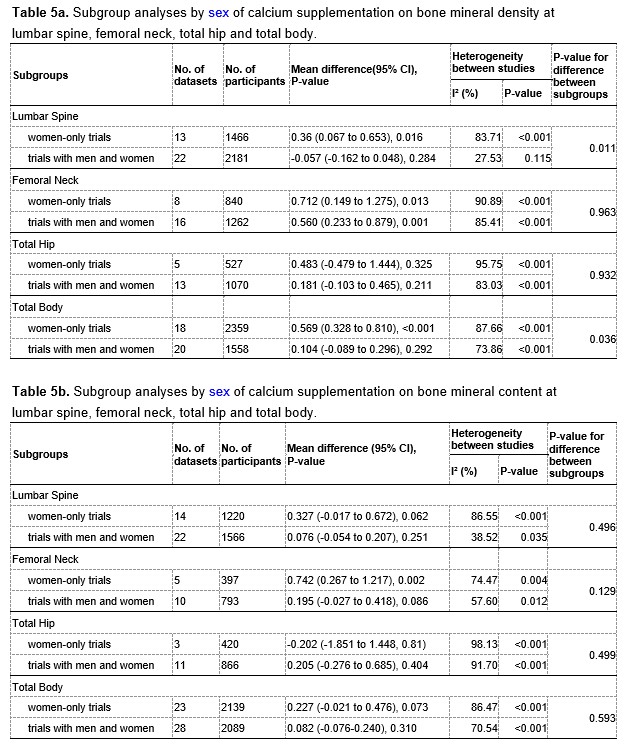

Similarly, we also performed subgroup analyses by sexes. Of all included trials, 23 trials focused on women only, and 20 trials involved both men and women participants, however these 20 trials did not report the results for men or women separately. We therefore divided the included trials into two subgroups: trials with women only and trials with both men and women. The corresponding results of subgroup analyses are showed in Table 5a and 5b at the end of this Author Response. The results showed that the subgroup with both men and women seemed to have less heterogeneous than the subgroup with women only, suggesting that sex may be a possible source of the observed heterogeneity.

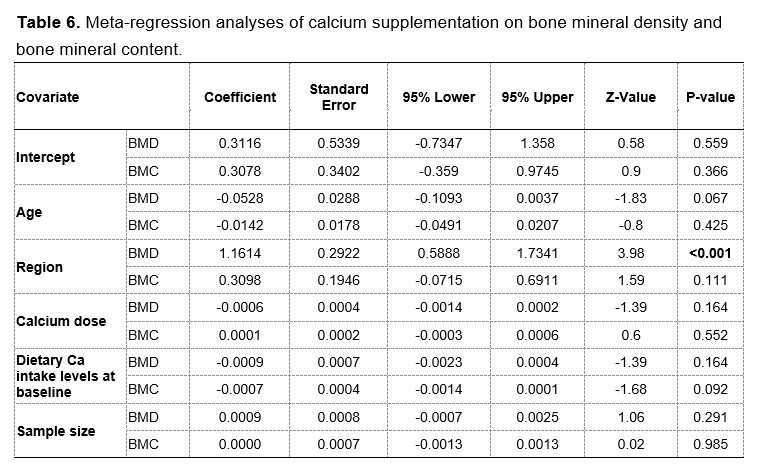

In addition, we were also aware of the large heterogeneity between trials and explored the possible sources through several additional approaches. Firstly, instead of using fixed-effects models, we have chosen random-effects models to summarize the effect estimates. Secondly, we performed meta-regression analyses by age, population regions, calcium doses, baseline intake and sample sizes to explain the intertrial heterogeneity. The results of meta-regression are provided in Table 6 at the end of this Author Response. The results suggested that this heterogeneity could be explained partially by differences in regions of participants.

We have updated the results and discussions about potential sources of heterogeneity in the revised manuscript, as follows:

In general, the heterogeneity between trials was obvious in the analysis for BMD (P<.001, I2=86.28%) and slightly smaller for BMC (P<.001, I2=79.28%). The intertrial heterogeneity was significantly distinct across the sites measured. Subgroup analyses and meta-regression analyses suggested that this heterogeneity could be explained partially by differences in age, duration, calcium dosages, types of calcium supplement, supplementation with or without vitamin D, baseline calcium intake levels, sex and region of participants. (See Lines 293-298 on Page 20 in the Main Text)

Several limitations need to be considered. First, there was substantial intertrial heterogeneity in the present analysis, which might be attributed to the differences in baseline calcium intake levels, regions, age, duration, calcium doses, types of calcium supplement, supplementation with or without vitamin D and sexes according to subgroup and meta-regression analyses. To take heterogeneity into account, we used random effect models to summarize the effect estimates, which could reduce the impact of heterogeneity on the results to some extent. (See Lines 394-399 on Page 24 in the Main Text)

- Rarity of RCTs focused on the 20-35-year age group.

Thank you very much for raising this point. We have comprehensively searched databases for eligible studies and found only three RCTs (Islam et al; Barger-Lux et al; Winters-Stone et al) focused on the 20-35-year age group. We did notice this fact as well. Because of this, we intend to perform a randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effects of calcium supplementation in this age group. In fact, this trial has already been started and is currently ongoing (Registration number: ChiCTR2200057644, http://www.chictr.org.cn/showproj.aspx?proj=155587).

In this open-label, randomized controlled trial, we will randomly assign (1:1) 116 subjects (age 18-22 years) to receive either or not calcium supplementation with milk (500 mL/day, contains about 500 mg/d calcium) for 6 months. The primary outcomes are bone mineral density and bone mineral content at the lumbar spine, femoral neck and total hip. The secondary outcomes are clinical indicators related to bone health, such as serum osteocalcin, bone-specific alkaline phosphatase, urinary deoxypyridinoline, etc. We will conduct the current trial with great care and diligence and look forward to the results of this trial.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

This systematic review and meta-analysis titled 'The effect of calcium supplementation in people under 35 years old: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials' provide good evidence for the importance of calcium supplementation at the age around the plateau of PBM. The statistical analyses were good overall and the manuscript was generally well written.

We are very grateful for your considerate comments and for your recognition to our work in this study. Your suggestions really helped us to improve the clarity of this manuscript.

One concern in this study is that RCTs included were substantially heterogenous in subjects, calcium types, duration, vitamin D supplements, etc. According to the inclusion criteria, RCTs with calcium or calcium plus vitamin D supplements with a placebo or no treatment were included in this study. However, no information about vitamin D supplementation was provided. Therefore, it seems unclear whether the effect of improving BMD or BMC is due to calcium alone or calcium plus vitamin D.

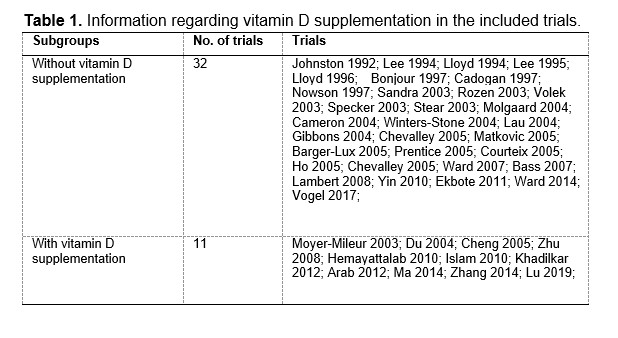

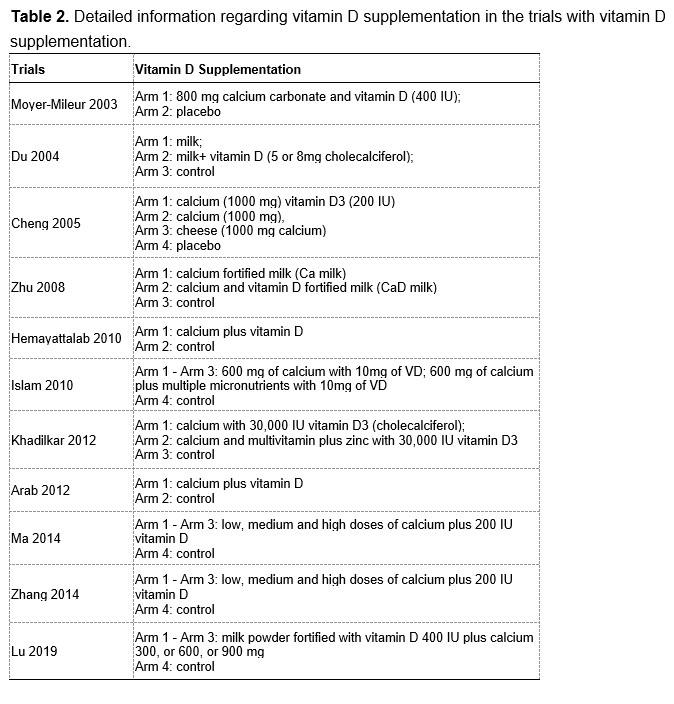

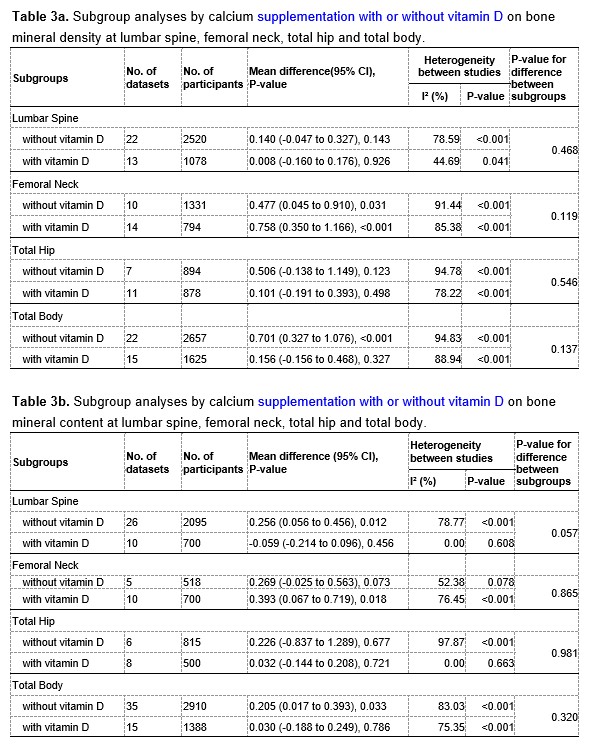

We are extremely grateful for your great patience and for your kind suggestions. According to your suggestions, we have added the corresponding analyses regarding calcium supplementation with or without vitamin D supplementation. Among the included RCTs, 32 trials used calcium-only supplementation (without vitamin D supplementation) and 11 trials used calcium plus vitamin D supplementation. The detailed information are provided in the Table 1 and 2 at the end of this Author Response. We have added subgroup analyses by vitamin D supplementation as you suggested, and the corresponding results are provided in Table 3a and 3b at the end of this Author Response.

When we pooled the data from the two subgroups separately, we found that calcium supplementation with vitamin D had greater beneficial effects on both the femoral neck BMD (MD: 0.758, 95% CI: 0.350 to 1.166, P < 0.001 VS. MD: 0.477, 95% CI: 0.045 to 0.910, P = 0.031) and the femoral neck BMC (MD: 0.393, 95% CI: 0.067 to 0.719, P = 0.018 VS. MD: 0.269, 95% CI: -0.025 to 0.563, P = 0.073) than calcium supplementation without vitamin D. However, for both BMD and BMC at the other sites (including lumbar spine, total hip, and total body), the observed effects in the subgroup without vitamin D supplementation appeared to be slightly better than in the subgroup with vitamin D supplementation. Therefore, these results suggested that calcium supplementation alone could improve BMD or BMC, although additional vitamin D supplementation may be beneficial in improving BMD or BMC at the femoral neck.

We have added relevant parts in the main text of the revised manuscript. (See Lines 258-263 on Pages 12-13 and Lines 367-374 on Page 23 in the Main Text)

As you mentioned, there exists large intertrial heterogeneity in this study, for which we compulsorily chose the random effect model, which was appropriate to get more conservative results. In addition, we did meta-subgroup analyses by calcium dose, sex, age, duration, regions, baseline calcium intake, types of calcium supplements, in order to explore possible sources of heterogeneity.

The results of subgroup analyses by dose of calcium supplementation are showed in Table 4a and 4b at the end of this Author Response. For both BMD and BMC at the lumbar spine and whole body, the intertrial heterogeneity was significantly smaller in the subgroup with a calcium supplementation dose greater than or equal to 1000 mg/day than that in the subgroup with a calcium supplementation dose less than 1000 mg/day, suggesting that different doses of calcium supplementation may be a potential source of the heterogeneity.

The results of subgroup analyses by sex are showed in Table 5a and 5b at the end of this Author Response. The intertrial heterogeneity was significantly smaller in the subgroup with both men and women than that in the subgroup with women only, also suggesting that sex could be a possible source of the heterogeneity.

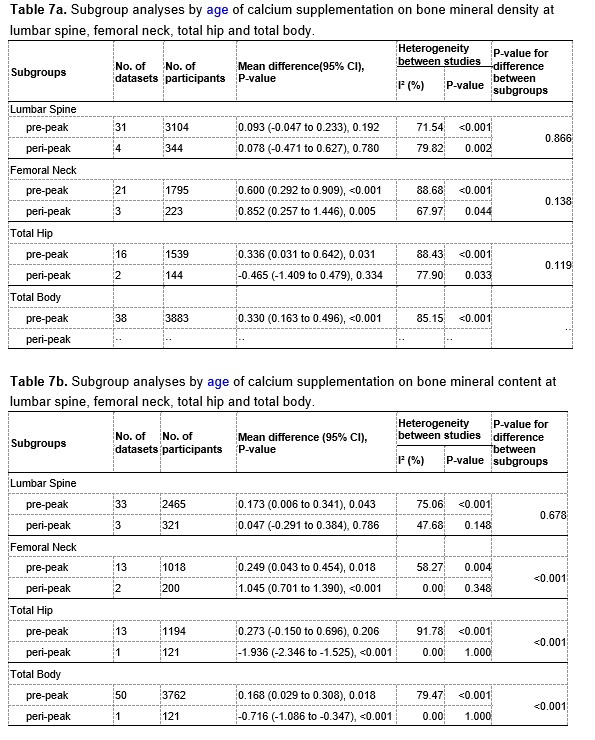

The results of subgroup analyses by age (pre-peak VS. peri-peak ) are showed in Table 7a and 7b at the end of this Author Response. The intertrial heterogeneity was significantly smaller in the peri-peak subgroup than that in the pre-peak subgroup, also suggesting that age may be a potential source of the heterogeneity.

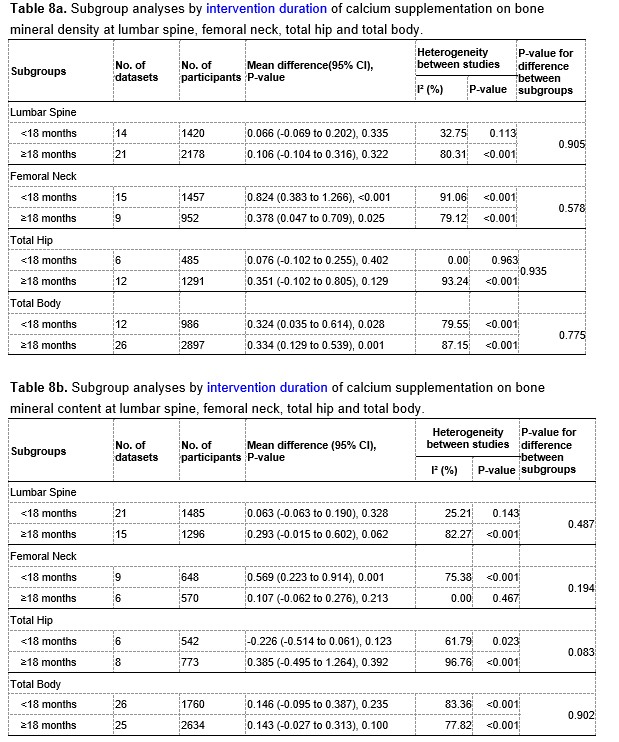

The results of subgroup analyses by intervention duration (pre-peak VS. peri-peak ) are showed in Table 8a and 8b at the end of this Author Response. For both BMD and BMC at the lumbar spine and total hip, the intertrial heterogeneity was smaller in the subgroup with a intervention period less than 18 months than that in the subgroup with a intervention period greater than or equal to 18 months, suggesting that intervention duration might be a potential source of the heterogeneity.

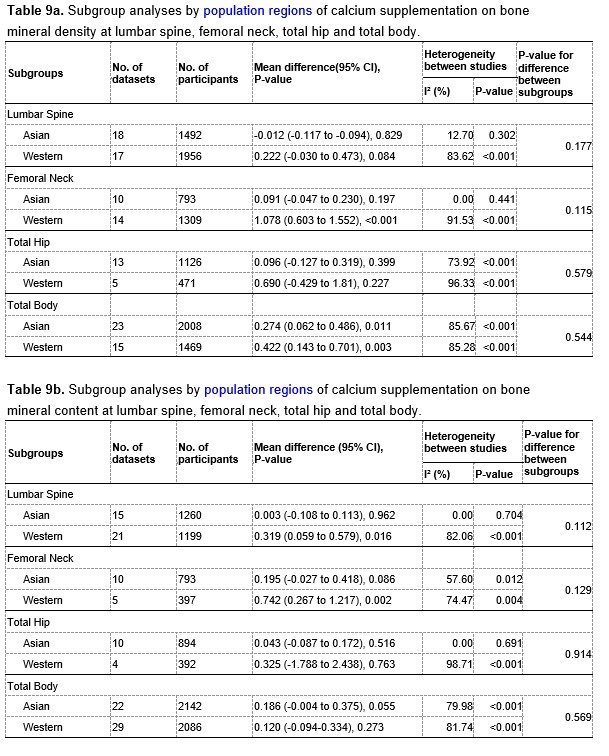

Table 9a and 9b at the end of this Author Response showed the results of subgroup analyses by population region. The intertrial heterogeneity was significantly smaller in the Asian subgroup than that in the Western subgroup, also suggesting that population region may be a source of the heterogeneity.

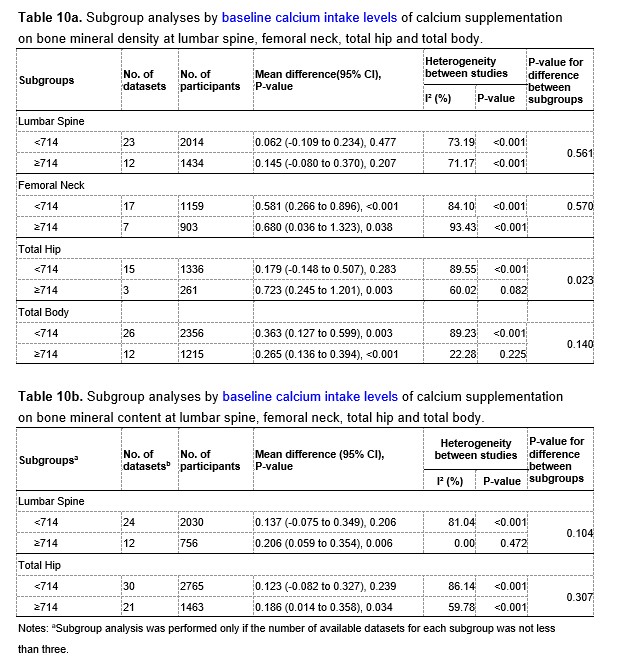

Table 10a and 10b at the end of this Author Response showed the results of subgroup analyses by dietary calcium intake levels at baseline. The intertrial heterogeneity was smaller in the subgroup with the dietary calcium intake level greater than or equal to 714 mg/day than that in the subgroup with the dietary calcium intake level lower than 714 mg/day, also suggesting that dietary calcium intake levels at baseline could be a potential source of the heterogeneity.

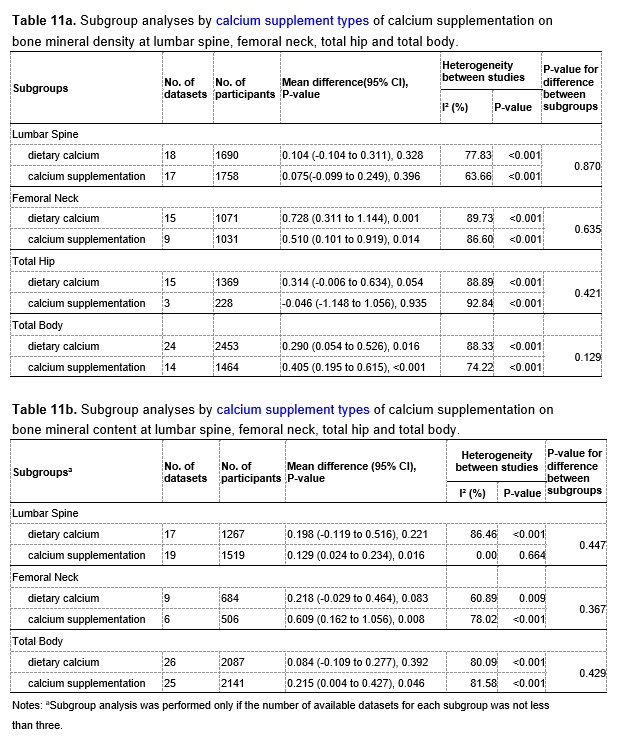

Table 11a and 11b at the end of this Author Response showed the results of subgroup analyses by types of calcium supplements. For both BMD and BMC at the lumbar spine, the intertrial heterogeneity was smaller in the subgroup with calcium supplementation than that in the subgroup with dietary calcium, also suggesting that types of calcium supplements might be a source of the heterogeneity.

In conclusion, the observed heterogeneity might be due to the differences in sex, age, regions of subjects, doses, intervention duration, and types of calcium supplementation, dietary calcium intake levels at baseline, and with or without vitamin D supplementation. We have updated the discussion on heterogeneity in the revised manuscript. (See Lines 394-397 on Pages 24 in the Main Text)

Thanks again for your comments, we have tried to analyze and explain the large heterogeneity through a variety of approaches, however, there may still remain some inadequacies. Please tell us directly if it needs further corrections, we will be very grateful and appreciate it, and try our best to revise this part of heterogeneity.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

This paper will be welcome for clinicians and researchers related to the field. The authors, applying a well-structured meta-analysis, showed that calcium supplementation or calcium intake during 20-35 years is better than the <20 years. The clinical impact is directly associated with improving the bone mass of the femoral neck, and thus proposes a window of intervention for osteoporosis treatment. The manuscript is very well prepared and represents a thorough analysis of available randomized controlled clinical trials, but a few issues require additional consideration.

We are very grateful for your considerate comments and for your recognition to our work in this study. Your comments are invaluable and have been very helpful in revising and improving our manuscript.

After a careful read of the literature, it is important to highlight that the paper is a statistically robust study with a well-delineated meta-analysis of youth-adult subjects. But, I would like better to understand why the authors didn't use other datasets such as WHO Global Index Medicus (Index Medicus for Africa, the Eastern Mediterranean Region, South-East Asia, and Western Pacific, and Latin America and the Caribbean Literature on Health Sciences, Index Medicus), ClinicalTrials.gov, and the WHO ICTRP.

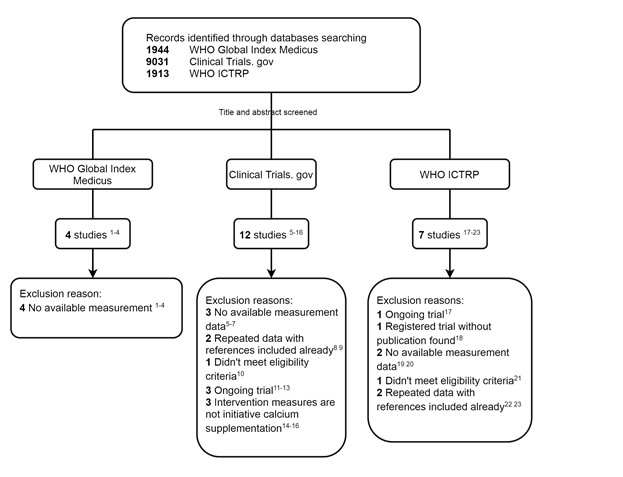

Thank you so much for your thoughtful advice and your generosity in recommending these datasets to us. Based on your advice, we thoroughly searched these databases (the detailed search terms are provided in the Appendix File at the end of this Author Response). We have identified 23 potentially related studies and registered trials in these databases. After careful screening and review, however, no new studies were ultimately included in this meta-analysis. Some studies, which had not been completed, are recruiting subjects, and some studies were duplicates of the RCTs we had included. Finally, no new additional trials were included in our meta-analysis. The detailed screening process and the reasons for exclusion are showed in Figure 1. These three additional global databases will provide us with more comprehensive information for our future studies, thank you very much for your suggestions and guidance.

Figure 1. Flow chart of search and selection

References:

- ID: emr-156089 (https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/gim/resource/en/emr-156089)

- ID: wpr-270003 (https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/gim/resource/en/wpr-270003)

- ID: lil-243754 (https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/gim/resource/en/lil-243754)

- ID: sea-23757 (https://pesquisa.bvsalud.org/gim/resource/en/sea-23757)

- ID: NCT00067925 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00067925?term=NCT00067925&draw=2&rank=1)

- ID: NCT00979511 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00979511?term=NCT00979511&draw=2&rank=1)

- ID: NCT00065247 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00065247?term=NCT00065247&draw=2&rank=1)

- Matkovic V, Landoll JD, Badenhop-Stevens NE, et al. Nutrition influences skeletal development from childhood to adulthood: a study of hip, spine, and forearm in adolescent females. J Nutr. 2004;134(3):701S-705S. doi:10.1093/jn/134.3.701S

- Barger-Lux MJ, Davies KM, Heaney RP. Calcium supplementation does not augment bone gain in young women consuming diets moderately low in calcium. J Nutr. 2005;135(10):2362-2366. doi:10.1093/jn/135.10.2362

- Cornes R, Sintes C, Peña A, et al. Daily Intake of a Functional Synbiotic Yogurt Increases Calcium Absorption in Young Adult Women. J Nutr. 2022;152(7):1647-1654. doi:10.1093/jn/nxac088

- ID: NCT00063011 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00063011?term=NCT00063011&draw=2&rank=1)

- ID: NCT00063024 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00063024?term=NCT00063024&draw=2&rank=1)

- ID: NCT01857154 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01857154?term=NCT01857154&draw=2&rank=1)

- ID: NCT00067600 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00067600?term=NCT00067600&draw=2&rank=1)

- ID: NCT00063037 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00063037?term=NCT00063037&draw=2&rank=1)

- ID: NCT00063050 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00063050?term=NCT00063050&draw=2&rank=1)

- ID: TCTR20190624002 (https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=TCTR20190624002)

- ID: JPRN-UMIN000024182 (https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=JPRN-UMIN000024182)

- ID: NCT02636348 (https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=NCT02636348)

- ID: ACTRN 12612000374864 (https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=ACTRN12612000374864)

- ID: NCT01732328 (https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=NCT01732328)

- ID: ISRCTN28836000 (https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=ISRCTN28836000)

- ID: ISRCTN84437785 (https://trialsearch.who.int/Trial2.aspx?TrialID=ISRCTN84437785)

We have also updated the literature search section and the flow chart in the main text of the revised manuscript, as follows:

We applied search strategies to the following electronic bibliographic databases without language restrictions: PubMed, EMBASE, ProQuest, CENTRAL (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials), WHO Global Index Medicus, Clinical Trials.gov, WHO ICTRP, China National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wanfang Data in April 2021 and updated the search in July 2022 for eligible studies addressing the effect of calcium or calcium supplementation, milk or dairy products with BMD or BMC as endpoints. (see Lines 80-85 on Page 5 and Figure 1 in the Main Text)

The manuscript compares two sources of participants (in line 233) evaluating the effect of improvements on the femoral neck being "obviously stronger in Western countries than in Asian countries". But, I didn't identify if the searches were conducted applying language restrictions. This is important because we can be considering the entire world or specific countries.

We are extremely grateful for your great patience and for your kind suggestions. We did not apply any language restrictions during the search process, as documented in the protocol of PROSPERO (CRD42021251275, https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=251275). Following your suggestion, we have added a description of this in the revised manuscript. (See Lines 80-81 on Page 5 in the Main Text)

During the search process, we did identify five eligible articles from the Chinese databases including China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI, https://www.cnki.net) and WanFang Data (https://www.wanfangdata.com.cn). However, we confirmed that these five studies were duplicates of the articles from the PubMed (PMID: 15230999; PMID: 17627404; PMID: 18296324; PMID: 20044757; PMID: 20460227). For those possibly relevant studies published in other languages than Chinese or English, the full text was downloaded and translated using DeepL translation website (https://www.deepl.com/translator) and then carefully reviewed. Ultimately, all included studies that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were published in English. In view of this, after a systematic and comprehensive search, especially with the addition of your suggested databases, we could assume that our current study has incorporated all original researches in this field worldwide, rather than only from specific countries or regions.

To explore whether the effects of calcium supplementation differ across different population regions, we performed subgroup analyses. Prior to the analysis, we hypothesized that the effect might be slightly better, or at least not worse, in populations with lower baseline dietary calcium intakes (lower baseline BMD/BMC levels) than that in populations with higher baseline dietary calcium intakes (higher baseline BMD/BMC levels). However, the results showed that the improvement effects on BMD at the femoral neck and total body and BMC at the femoral neck and lumbar spine were obviously stronger in Western countries than in Asian countries. These findings are likely to be contrary to our common sense, which is, that under normal circumstances, the effects of calcium supplementation should be more obvious in people with lower calcium intakes than in those with higher calcium intakes. Therefore, this issue needs to be tested and confirmed in future trials.

The manuscript does not describe which version was used with the RoB tool.

Thank you for your suggestion. As you mentioned, we completed the description of RoB tool in the Methods section, as follows:

The quality of the included RCTs was assessed independently by two reviewers (SYL, HNJ) based on the Revised Cochrane Risk-of-Bias Tool for Randomized Trials (RoB 2 tool, version 22 August 2019), and each item was graded as low risk, high risk and some concerns. (See Lines 101-103 on Page 6 in the Main Text)

Figures and Supplementary: No critique.

Thanks for your kind comments and for your recognition to our work in this study.

Appendix 1

Search strategy • WHO Global Index Medicus:

(tw:(calcium)) OR (mj:(calcium)) OR (tw:(calcium carbonate)) OR (tw:(calcium citrate)) OR (tw:(calcium pills)) OR (tw:(calcium supplement)) OR (tw:(Ca2)) OR (tw:(dairy product)) OR (tw:(milk)) OR (tw:(yogurt)) OR (tw:(cheese)) OR (tw:(dietary supplement)) AND (tw:(bone density)) OR (tw:(bone mineral density)) OR (tw:(bone mineral content))

• ClinicalTrials.gov

(calcium) OR (calcium supplementation) OR (milk) OR (dairy product) OR (yogurt) OR (cheese) Applied Filters: Interventional (clinical trial); Child (birth–17); Adult (18–64)

• WHO ICTRP

(calcium) OR (milk) OR (dairy) OR (yogurt) OR (cheese) in the Intervention

-

Evaluation Summary:

This is a systematic review by meta-analysis about the effect of calcium supplementation on bone health in people under 35 years old. The authors found that calcium supplementation can significantly improve BMD and BMC in young people. Moreover, a better effect of calcium supplementation was shown in people who are at the plateau of their PBM. A unique feature of this study is that it focused on people at the age before achieving PBM or age at the plateau of PBM, which is different from previous studies that mainly focused on the elderly or children.

(This preprint has been reviewed by eLife. We include the public reviews from the reviewers here; the authors also receive private feedback with suggested changes to the manuscript. The reviewers remained anonymous to the authors.)

-

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Although a bunch of studies have been carried out to see whether calcium supplementation is a prerequisite for the promotion of bone health or prevention of bone diseases, this is the first trial to see its effect on the population whose age is reaching peak bone mass. Outcomes are clear and justified by sound methodology. Also, the message from this systematic review could directly influence the clinical decision on who might gain benefit from calcium supplementation.

Strengths of this study are:

This is the first systematic review by meta-analysis to focus on people at the age before achieving peak bone mass (PBM) and at the age around the PBM.

Detailed subgroup and sensitivity analyses drew consistent and clear results.

Limitations of this study are:

Substantial intertrial heterogeneity should be …

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Although a bunch of studies have been carried out to see whether calcium supplementation is a prerequisite for the promotion of bone health or prevention of bone diseases, this is the first trial to see its effect on the population whose age is reaching peak bone mass. Outcomes are clear and justified by sound methodology. Also, the message from this systematic review could directly influence the clinical decision on who might gain benefit from calcium supplementation.

Strengths of this study are:

This is the first systematic review by meta-analysis to focus on people at the age before achieving peak bone mass (PBM) and at the age around the PBM.

Detailed subgroup and sensitivity analyses drew consistent and clear results.

Limitations of this study are:

Substantial intertrial heterogeneity should be considered in terms of dose effect of calcium supplementation and differences between both sexes etc.

Rarity of RCTs focused on the 20-35-year age group.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

This systematic review and meta-analysis titled 'The effect of calcium supplementation in people under 35 years old: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials' provide good evidence for the importance of calcium supplementation at the age around the plateau of PBM. The statistical analyses were good overall and the manuscript was generally well written.

One concern in this study is that RCTs included were substantially heterogenous in subjects, calcium types, duration, vitamin D supplements, etc. According to the inclusion criteria, RCTs with calcium or calcium plus vitamin D supplements with a placebo or no treatment were included in this study. However, no information about vitamin D supplementation was provided. Therefore, it seems unclear whether the effect of improving BMD or …

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

This systematic review and meta-analysis titled 'The effect of calcium supplementation in people under 35 years old: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials' provide good evidence for the importance of calcium supplementation at the age around the plateau of PBM. The statistical analyses were good overall and the manuscript was generally well written.

One concern in this study is that RCTs included were substantially heterogenous in subjects, calcium types, duration, vitamin D supplements, etc. According to the inclusion criteria, RCTs with calcium or calcium plus vitamin D supplements with a placebo or no treatment were included in this study. However, no information about vitamin D supplementation was provided. Therefore, it seems unclear whether the effect of improving BMD or BMC is due to calcium alone or calcium plus vitamin D.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

This paper will be welcome for clinicians and researchers related to the field. The authors, applying a well-structured meta-analysis, showed that calcium supplementation or calcium intake during 20-35 years is better than the <20 years. The clinical impact is directly associated with improving the bone mass of the femoral neck, and thus proposes a window of intervention for osteoporosis treatment. The manuscript is very well prepared and represents a thorough analysis of available randomized controlled clinical trials, but a few issues require additional consideration.

After a careful read of the literature, it is important to highlight that the paper is a statistically robust study with a well-delineated meta-analysis of youth-adult subjects.

But, I would like better to understand why the authors didn't …Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

This paper will be welcome for clinicians and researchers related to the field. The authors, applying a well-structured meta-analysis, showed that calcium supplementation or calcium intake during 20-35 years is better than the <20 years. The clinical impact is directly associated with improving the bone mass of the femoral neck, and thus proposes a window of intervention for osteoporosis treatment. The manuscript is very well prepared and represents a thorough analysis of available randomized controlled clinical trials, but a few issues require additional consideration.

After a careful read of the literature, it is important to highlight that the paper is a statistically robust study with a well-delineated meta-analysis of youth-adult subjects.

But, I would like better to understand why the authors didn't use other datasets such as WHO Global Index Medicus (Index Medicus for Africa, the Eastern Mediterranean Region, South-East Asia, and Western Pacific, and Latin America and the Caribbean Literature on Health Sciences, Index Medicus), ClinicalTrials.gov, and the WHO ICTRP.

The manuscript compares two sources of participants (in line 233) evaluating the effect of improvements on the femoral neck being "obviously stronger in Western countries than in Asian countries". But, I didn't identify if the searches were conducted applying language restrictions. This is important because we can be considering the entire world or specific countries.The manuscript does not describe which version was used with the RoB tool.

Figures and Supplementary: No critique.

-