A tripartite structure, the complex nuclear receptor element (cNRE), is a c is-regulatory module of viral origin required for atrial chamber preferential gene expression

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

Evaluation Summary:

In this manuscript Nunes Santos et al. use a combination of computation and experimental methods to identify and characterize a cis-regulatory element that mediates expression of the quail Slow Myosin Heavy Chain III (SMyHC III) gene in the heart. The study contributes to our understanding of how genes can be expressed differentially in the atrial and ventricular chambers of the heart. The evidence for the newly-identified gene regulatory sequence, and its origin, in exclusively directing these gene expression differences could be stronger. This study is of potential interest to readers in the fields of developmental biology, evolution, gene regulation, and biology of repeats.

(This preprint has been reviewed by eLife. We include the public reviews from the reviewers here; the authors also receive private feedback with suggested changes to the manuscript. Reviewer #3 agreed to share their name with the authors.)

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

Optimal cardiac function requires appropriate contractile proteins in each heart chamber. Atria require slow myosins to act as variable reservoirs, while ventricles demand fast myosin for swift pumping functions. Hence, myosin is under chamber-biased cis -regulatory control to achieve this functional distribution. Failure in proper regulation of myosin genes can lead to severe congenital heart dysfunction. The precise regulatory input leading to cardiac chamber-biased expression remains uncharted. To address this, we computationally and molecularly dissected the quail Slow Myosin Heavy Chain III (SMyHC III) promoter that drives specific gene expression to the atria to uncover the regulatory information leading to chamber expression and understand their evolutionary origins. We show that SMyHC III gene states are autonomously orchestrated by a complex nuclear receptor cis -regulatory element (cNRE), a 32- bp sequence with hexanucleotide binding repeats. Using in vivo transgenic assays in zebrafish and mouse models, we demonstrate that preferential atrial expression is achieved by the combinatorial regulatory input composed of atrial activation motifs and ventricular repression motifs. Through comparative genomics, we provide evidence that the cNRE emerged from an endogenous viral element, most likely through infection of an ancestral host germline. Our study reveals an evolutionary pathway to cardiac chamber-specific expression.

Article activity feed

-

Author Response

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The authors reveal dual regulatory activity of the complex nuclear receptor element (cNRE; contains hexads A+B+C) in cardiac chambers and its evolutionary origin using computational and molecular approaches. Building upon a previous observation that hexads A and B act as ventricular repressor sequences, in this study the authors identify a novel hexad C sequence with preferential atrial expression. The authors also reveal that the cNRE emerged from an endogenous viral element using comparative genomic approaches. The strength of this study is in a combination of in silico evolutionary analyses with in vivo transgenic assays in both zebrafish and mouse models. Rapid, transient expression assays in zebrafish together with assays using stable, transgenic mice demonstrate dual functionality of …

Author Response

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The authors reveal dual regulatory activity of the complex nuclear receptor element (cNRE; contains hexads A+B+C) in cardiac chambers and its evolutionary origin using computational and molecular approaches. Building upon a previous observation that hexads A and B act as ventricular repressor sequences, in this study the authors identify a novel hexad C sequence with preferential atrial expression. The authors also reveal that the cNRE emerged from an endogenous viral element using comparative genomic approaches. The strength of this study is in a combination of in silico evolutionary analyses with in vivo transgenic assays in both zebrafish and mouse models. Rapid, transient expression assays in zebrafish together with assays using stable, transgenic mice demonstrate dual functionality of cNRE depending on the chamber context. This is especially intriguing given that the cNRE is present only in Galliformes and has originated likely through viral infection. Interestingly, there seem to be some species-specific differences between zebrafish and mouse models in expression response to mutations within the cNRE. Taken together, these findings bear significant implications for our understanding of dual regulatory elements in the evolutionary context of organ formation.

We thank reviewer 1 for the thorough review and are very satisfied with his favorable view of our manuscript. We also thank reviewer 1 for suggestions and opportunities to further clarify some relevant issues.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Nunes Santos et al. investigated the gene regulatory activity of the promoter of the quail myosin gene, SMyHC III, that is expressed specifically in the atria of the heart in quails. To do so, they computationally identified a novel 6-bp sequence within the promoter that is putatively bound by a nuclear receptor transcription factor, and hence is a putative regulatory sequence. They tested this sequence for regulatory activity using transgenic assays in zebrafish and mice, and subjected this sequence to mutagenesis to investigate whether gene regulatory effects are abrogated. They define this sequence, together with two additional known 6-bp regulatory sequences, as a novel regulatory sequence (denoted cNRE) necessary and sufficient for driving atrial-specific expression of SMyHC III. This cNRE sequence is shared across several galliform species but appears to be absent in other avian species. The authors find that there is sequence homology between the cNRE and several virus genomes, and they conclude that this regulatory sequence arose in the quail genome by viral integration.

Strengths: The evolutionary origins of gene regulatory sequences and their impact on directing tissue-specific expression are of great interest to geneticists and evolutionary biologists. The authors of this paper attempt to bring this evolutionary perspective to the developmental biology question of how genes are differentially expressed in different chambers of the heart. The authors test for regulatory activity of the putative regulatory sequence they identified computationally in both zebrafish and mouse transgenic assays. The authors disrupt this sequence using deletions and mutagenesis, and introduce a tandem repeat of the sequence to a reporter gene to determine its consequences on chamber activity. These experiments demonstrate that the identified sequence has regulatory activity.

We appreciate the thorough review of our manuscript and are very stimulated by the reviewer’s understanding of the contents we presented. We will take the liberty to comment after the reviewer’s considerations, in the hope to better answer the relevant points.

Weaknesses: There are several decisions and assumptions that have been made by the authors, the reasons for which have not been articulated. Firstly, the rationale for the approach is not clear. The study is a follow-up to work previously performed by the authors which identified two 6-bp sequences important for controlling atrial-specific expression of the quail SMyHC III gene. This study appears to be motivated by the fact that these two sequences, bound by nuclear receptors, do not fully direct chamber-specific expression, and therefore this study aims to find additional regulatory sequences. It is assumed that any additional regulatory sequences should also be bound by nuclear receptors, and be 6-bp in length, and therefore the authors search for 6-bp sequences bound by nuclear receptors. It is not clear what the input sequence for this analysis was.

Thank you for giving us the opportunity to clarify our rational. Our approach is justified by the natural progression in the understanding of the mechanisms involved in preferential atrial expression by the SMyHC III promoter. The groundwork was solidly laid down by Wang and colleagues (see references as below). They mapped potential atrial stimulators and ventricular repressors throughout the SMyHC III promoter using atrial and ventricular cultures, respectively. Wang and colleagues pinned down the relevant regulators. First between -840 and -680 bp upstream from the transcription start site, then inside this nucleotide stretch, then in the 72-bp fragment contained between -840 and -680 bp, then identified the ventricular repressor in Hexads A and B inside the 72-bp sequence (see references below). We, in this manuscript, contributed with the identification of Hexad C (immediately downstream of Hexads A and B) as a potential nuclear receptor binding site and as a bona fide atrial activator. In summary, our work represents a logical conclusion of previous work by Wang and colleagues. We continued the process of narrowing down sequences previously proven to contain atrial activators (that were unknown before our present work) and ventricular repressors (that were already described).

Why did we use nuclear receptors as models for the putative cardiac chamber regulators binding to the cNRE? This is because previous work by Wang et al., 1996, 1998, 2001 and by Bruneau et al., 2001 showed that the 5’ portion of the cNRE (Hexads A and B) is indeed a hub for the integration of signals conveyed by nuclear receptors. Originally, Wang et al., 1996 showed that the VDR response element is a ventricular repressor acting via the 5’ portion of the cNRE. In a subsequent manuscript, Wang et al., 1998 showed that both RAR and VDR bind the 5’ portion of the cNRE. Bruneau et al., 2001 showed, by crossing IRX4 knockout mice with SMyHC III-HAP mice (Xavier-Neto et al., 1999), that IRX4 plays the role of a repressor of SMyHC III-HAP expression. Finally, Wang et al., 2001 showed that IRX4 interacts with RXR bound to the 5’ portion of the cNRE to inhibit ventricular expression.

Why was the 3’ Hexad included as a research subject? Very early on in our work it was noted that 3’ of the original VDR response element (Hexads A and B), described by Wang et al., 1996 and 1998 as a ventricular repressor, there was a sequence (Hexad C) with almost equal binding potential to nuclear receptors as Hexads A and B (as initially judged on the basis of comparisons with canonical nuclear receptor binding sequences, but later on confirmed by in silico profiling of nuclear receptor binding, see below). This discovery prompted us to design point mutants in the 3’ portion of the cNRE to investigate whether Hexad C contained relevant regulators of heart chamber expression. These analyses revealed a strong atrial activator in the mouse (the missing atrial activator from Wang et al., 1996, 1998, 2001).

Wang, G. F., Nikovits, W., Schleinitz, M., and Stockdale, F. E. (1996). Atrial chamber-specific expression of the slow myosin heavy chain 3 gene in the embryonic heart. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 19836-19845.

Wang, G. F., Nikovits, W. Jr., Schleinitz, M., and Stockdale, F. E. (1998). A positive GATA element and a negative vitamin D receptorlike element control atrial chamber-specific expression of a slow myosin heavy-chain gene during cardiac morphogenesis. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 6023-6034.

Xavier-Neto, J., Neville, C. M., Shapiro, M. D., Houghton, L., Wang, G. F., Nikovits, W. Jr, Stockdale, F. E., and Rosenthal, N. (1999). A retinoic acid-inducible transgenic marker of sino-atrial development in the mouse heart. Development 126, 2677-2687.

Bruneau, B. G., Bao, Z. Z., Fatkin, D., Xavier-Neto, J., Georgakopoulos, D., Maguire, C. T., Berul, C. I., Kass, D. A., Kuroski-de Bold, M. L., de Bold, A. J., Conner, D. A., Rosenthal, N., Cepko, C. L., Seidman, C. E., and Seidman, J. G. (2001). Cardiomyopathy in Irx4-deficient mice is preceded by abnormal ventricular gene expression. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 1730-1736.

Wang, G. F., Nikovits, W. Jr., Bao, Z.Z., and Stockdale, F.E. (2001). Irx4 forms an inhibitory complex with the vitamin D and retinoic X receptors to regulate cardiac chamber-specific slow MyHC3 expression. J Biol Chem. 276, 28835-28841.

The methods section mentions the cNRE sequence, but this is their newly defined regulatory sequence based on the newly identified 6-bp sequence. It is therefore unclear why Hexad C was identified to be of interest, and not the GATA binding site for example, and whether other sequences in the promoter might have stronger effects on driving atrial-specific expression.

As far as the existence of binding sites other than Hexads A, B, and C, we cannot, formally, exclude the possibility that there may be other relevant regulators of the* SMyHC III* gene. But we note that the sequences that we utilized were previously mapped through deletion mutant promoter approach by Wang et al., 1996 as the most powerful atrial activator(s) and ventricular repressor(s). We addressed these concerns in a new session entitled “Limitations of our work”.

Concerning GATA regulation, Wang et al., 1996, 1998 characterized a GATA-4 site that drives generalized (atrial and ventricular) cardiac expression in quail cultures. However, we were unable to identify any relevant changes in cardiac expression in mutant GATA SMyHC III-HAP transgenic mouse lines produced with the same mutated promoter sequences described by Wang et al., 1996, 1998.

Finding Hexad C as an atrial activator was an experimental finding. We identified it as such because we had two important inputs. First, in 1997, we consulted with Ralff Ribeiro, a specialist on nuclear receptors and he pointed out that downstream of the Hexad A + Hexad B VDRE/RARE (the ventricular repressor), there was a sequence with good potential for a nuclear receptor binding motif. This was exactly Hexad C. Then, we confirmed its potential for nuclear receptor binding by nuclear receptor profiling. After these two pieces of evidence, we thought that there was enough evidence to justify a mutant construct (Mut C). The experimental results we obtained in transgenic mice and zebrafish are consistent with the hypothesis that Hexad C does contain the long sought atrial activator predicted by Wang et al., 1996 in atrial cultures. This seems to be the most important atrial activator (a seven-fold activator) predicted by a deletion approach to be located between -840 and 680 bp in Wang et al., 1996.

Wang, G. F., Nikovits, W., Schleinitz, M., and Stockdale, F. E. (1996). Atrial chamber-specific expression of the slow myosin heavy chain 3 gene in the embryonic heart. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 19836-19845.

Wang, G. F., Nikovits, W. Jr., Schleinitz, M., and Stockdale, F. E. (1998). A positive GATA element and a negative vitamin D receptorlike element control atrial chamber-specific expression of a slow myosin heavy-chain gene during cardiac morphogenesis. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 6023-6034.

Indeed, the zebrafish transgenic assays use the 32 bp cNRE, while in the mouse transgenic assays, a 72 bp region is used. This choice of sequence length is not justified.

As stated above, our rational was built as a continuation of the thorough work by Wang and colleagues in progressively narrowing down the location of relevant atrial stimulators and ventricular repressors. Throughout our work, we sought to obtain maximal coherence with previous studies (see references below) and to simultaneously probe cNRE function at an increased resolution. For that, we utilized previously described mutant SMyHC III promoter constructs (Wang et al., 1996) and introduced novel site-directed dinucleotide substitution mutants of individual Hexads in the SMyHC III promoter.

Wang, G. F., Nikovits, W., Schleinitz, M., and Stockdale, F. E. (1996). Atrial chamber-specific expression of the slow myosin heavy chain 3 gene in the embryonic heart. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 19836-19845.

Wang, G. F., Nikovits, W. Jr., Schleinitz, M., and Stockdale, F. E. (1998). A positive GATA element and a negative vitamin D receptorlike element control atrial chamber-specific expression of a slow myosin heavy-chain gene during cardiac morphogenesis. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 6023-6034.

Xavier-Neto, J., Neville, C. M., Shapiro, M. D., Houghton, L., Wang, G. F., Nikovits, W. Jr, Stockdale, F. E., and Rosenthal, N. (1999). A retinoic acid-inducible transgenic marker of sino-atrial development in the mouse heart. Development 126, 2677-2687.

Bruneau, B. G., Bao, Z. Z., Fatkin, D., Xavier-Neto, J., Georgakopoulos, D., Maguire, C. T., Berul, C. I., Kass, D. A., Kuroski-de Bold, M. L., de Bold, A. J., Conner, D. A., Rosenthal, N., Cepko, C. L., Seidman, C. E., and Seidman, J. G. (2001). Cardiomyopathy in Irx4-deficient mice is preceded by abnormal ventricular gene expression. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 1730-1736.

Wang, G. F., Nikovits, W. Jr., Bao, Z.Z., and Stockdale, F.E. (2001). Irx4 forms an inhibitory complex with the vitamin D and retinoic X receptors to regulate cardiac chamber-specific slow MyHC3 expression. J Biol Chem. 276, 28835-28841.

The decisions about which bases to mutate in the three hexads are also not clear. Why are the first two bases mutated in Hexad B and C and the whole region mutated in Hexad A? Is there a reason to believe these bases are particularly important?

As for the reasons behind mutation of the first two bases in Hexad B and Hexad C, there were two:

One reason is because these point mutations in Hexads B and C were planned after the publication of Wang et al., 1996, which defined the major role of Hexad A in ventricular repression. After this discovery, we decided that a higher level of resolution in our mutation approach would be a better way to search for additional regulators of SMyHC III expression, including the atrial regulator that was readily apparent from the results shown in Wang et al., 1996, but had not yet been described.

The second reason is because the two first nucleotides (purines) in a nuclear-receptor binding hexad are critical for the interaction between target DNA and transcription factors of the nuclear receptor family. Substituting pyrimidines for purines in the two first positions of an hexad drastically reduces the affinity of a nuclear response element, and that is why we chose to use TT substitutions in our mutant constructs. Please refer to: Umesono et al., Cell, 1991 65: 12551266 for a review; Mader et al., J Biol Chem, 1993 268:591-600 for a mutation study; Rastinejad et al., EMBO J., 2000 19:1045-1054 for a crystallographic study (as well as additional references listed below).

Mader, S., Chen, J. Y., Chen, Z., White, J., Chambon, P., and Gronemeyer, H. (1993). The patterns of binding of RAR, RXR and TR homo- and heterodimers to direct repeats are dictated by the binding specificites of the DNA binding domains. EMBO J. 12, 50295041.

Ribeiro, R. C., Apriletti, J. W., Yen, P.M., Chin, W. W., and Baxter, J. D. (1994). Heterodimerization and deoxyribonucleic acid-binding properties of a retinoid X receptor-related factor. Endocrinology.135, 2076-2085.

Zhao, Q., Chasse, S. A., Devarakonda, S., Sierk, M. L., Ahvazi, B., and Rastinejad, F. (2000). Structural basis of RXR-DNA interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 296, 509-520.

Shaffer, P. L. and Gewirth, D. T. (2002). Structural basis of VDR-DNA interactions on direct repeat response elements. EMBO J. 21, 2242-2252.

The control mutant also has effects on the chamber distribution of GFP expression.

We note that, in the mouse, MutS did not produce any major changes from the typical wild type phenotypes linked to SMyHC III-HAP transgenic hearts. We concluded, based on our data, that the spacing mutant worked reasonably well as a negative mutation control in mice. We agree that it would have been particularly elegant if a spacing mutant designed for the mouse context worked in the exact same way in the zebrafish. However, the fact that there are slight differences in behavior for the mutated “spacing” constructs in species separated by, millions of years of independent evolution is not really surprising, given that the amino acid sequence of transcription factors can diverge and co-evolve with binding nucleotides and end up drifting quite substantially from an ancestral setup. As we reiterate below, we consider more fundamental the fact that the cNRE is actually able to bias cardiac expression towards a model of preferential atrial expression, even in the context of species separated by millions of years of independent evolution.

Two claims in the paper have weak evidence. Firstly, the conclusion that the cNRE is necessary and sufficient for driving preferential expression in the atrium. Deleting the cNRE does reduce the amount of atrial reporter gene expression but there is not a "conversion" from atrial to ventricular expression as mentioned in line 205. Similarly, a fusion of 5 tandem repeats of the cNRE can induce expression of a ventricular gene in the atria (I'm assuming a single copy is insufficient), but does not abolish ventricular expression.

We agree that our labelling of the cNRE is perhaps too strong, and we have toned it down accordingly to incorporate the much more equilibrated concept that the cNRE biases cardiac expression towards a model of preferential atrial expression.

However, after the corrections suggested, we believe our assertion is now justified. We show that in the mouse, removal of the cNRE is followed by a major reduction of atrial expression coupled to the release of a low, but quite clear level of expression in the ventricles, when compared to the transgenic mouse harboring the wild type SMyHC III promoter. Note that, as expected, the relative power of the cNRE to establish preferential atrial expression is higher in the mouse (a mammal) than it is in the zebrafish (a teleost), which is biologically sound, as mammals and avians are closer, phylogenetically, than teleosts and avians. Yet, the direction of change of expression in atria and ventricles was exactly as expected, if a given motif responsible for preferential atrial expression was removed (the cNRE in our case), that is: marked reduction in atrial expression and small (albeit clearly evident) release of ventricular expression. We believe that these directional changes observed in species separated by millions of years of independent evolution constitute very good biological evidence for the role of the cNRE in driving preferential atrial expression.

Concerning the 5x fusion of cNREs, we chose to produce this multimer for safety purposes only, because we did not want to risk performing incomplete experiments and having to repeat them. However, more to the point, we later compared the efficiency of one (1) versus five (5) cNRE copies in a cell culture context and the results were not different.

Secondly, the authors claim that the cNRE regulatory sequence arose from viral integration into the genomes of galliform species. While this is an attractive mechanism for explaining novel regulatory sequences, the evidence for this is based purely on sequence homology to viral genomes. And this single observation is not robust as the significance of the sequence matches does not appear to be adjusted for sequence matches expected by chance. The "evolutionary pathway" leading to the direction of chamber-specific expression in the heart as highlighted in the abstract has therefore not been demonstrated.

We agree with the reviewer. Because of space constraints, we decided to omit a substantial part of our work from the initial submission of the manuscript. We now include the relevant data in the revised version. We thus mapped the phylogenetic origins of the SMyHC III family of slow myosins and then established how and when the cNREs became topologically associated with the SMyHC III gene. To do that, we repeat masked all available sequences from avian SMyHC III orthologs. As it will become clear below, the cNRE is a rare sequence, rather than a low complexity repeat. Our search for cNREs outside of the quail context (Coturnix coturnix) followed two independent lines. First, we took a scaled, evolution-oriented approach. Initially, we looked for cNREs in species close to the quail (i.e., Galliformes) and then progressively farther, to include derived (i.e., Passeriformes) and basal avians (i.e., Paleognaths) as well as external groups such as crocodilians. While pursuing this line of investigation, it became clear that the cNRE was a rare form of repetitive element, which showed a conserved topological relationship with the SMyHC III gene (i.e., cNREs flanked the SMyHC III genes at 5’ and 3’ regions). Using this topological relationship as a character, we determined when it appeared during avian evolution and then set out to establish the likely origins of this rare repetitive motif. This search for the origins of the cNRE entailed comparisons to databases of repetitive genome elements, until the extreme telomeric nature of the SMyHC III gene became evident. This finding directed us to the fact that the hexad nature of the cNRE is reminiscent of the hexameric character of telomeric direct repeats. Because direct telomeric repeats are exactly featured in the genomes of avian DNA viruses that can infect the germline and integrate into the avian genome, we focused our search for the cNRE on the members of the subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae (Morissette & Flamand, 2010). In this search, we utilized the human herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV1) as a general model for herpes viruses, and a set of four (4) members of the Alphaherpesvirinae family that specifically infect Galliformes (i.e., GaHV1, the virus responsible for avian infectious laryngotracheitis in chicken, GaHV2, the Marek’s disease virus, GaHV3, a non-pathogenic virus, and MeHV1, the non-pathogenic Meleagrid herpesvirus 1 capable of infecting chicken and wild turkey) (Waidner et al., 2009). The search for cNREs in Alphaherpesvirinae was successful. We found six (6) cNRE hits in HSV1, one (1) in GaHV1, and none in MeHV1, GaHV2, and GaHV3. Our evolution-directed approach thus led to the direct recognition that cNREs can be found in the genomes of a family of viruses that contain members that infect avians and integrate their double-stranded DNA into the host germline (Morissette & Flamand, 2010). Therefore, as a second independent approach, as pointed out by the reviewer, we set out to further extend this proof of concept by broadening our search to all known sequenced viruses and perform an unbiased, internally consistent, and quantitative analysis of cNRE presence in viral genomes, as already reported in the initial submission of this manuscript.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Summary:

In this manuscript Nunes Santos et al. use a combination of computation and experimental methods to identify and characterize a cis-regulatory element that mediates expression of the quail Slow Myosin Heavy Chain III (SMyHC III) gene in the heart (specifically in the atria). Previous studies had identified a cis-regulatory element that can drive expression of SMyHC III in the heart, but not specifically (solely) in the atria, suggesting additional regulatory elements are responsible for the specific expression of SMyHC III in the atria as opposed to other elements of the heart. To identify these elements Nunes Santos et al. first used a bioinformatic approach to identify potentially functional nuclear receptor binding sites ("Hexads") in the SMyHC III promoter; previous studies had already shown that two of these Hexads are important for SMyHC III promoter function. They identified a previously unknown third Hexad within the promoter, and propose that the combination of these three (called the complex Nuclear Receptor Element or cNRE) is necessary and sufficient for specific atrial expression of SMyHC III. Next, they use experimental methods to functionally characterize the cNRE including showing that the quail SMyHC III promoter can drive green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression the atrium of developing zebrafish embryos and that the cNRE is necessary to drive the expression of the human alkaline phosphatase reporter gene (HAP) in transgenic mouse atria. Additional experiments show that the cNRE is portable regulatory element that can drive atrial expression and demonstrate the importance of the three Hexad parts. These data demonstrating that the cNRE mediates atrial-specific expression is well-done and convincing. The authors also note the possibility that the cNRE might be derived from an endogenous viral element but further data are needed to support the hypothesis that the cNRE is of viral origin.

Strengths:

- The experimental work demonstrating that the cNRE is a regulatory element that can mediate the atrial-specific expression of SMyHC III.

We thank reviewer 3 for this thorough appreciation of our work and are pleased with the evaluation of our manuscript’s potential.

Weaknesses:

- Justification for use of different regulatory elements in the zebrafish (32 bp cNRE) and the mouse transgenic assays (72 bp cNRE), and discussion of the impact of this difference on the results/interpretation.

In general, throughout our work, we sought to obtain maximal coherence with previous studies (see references below) and to simultaneously probe cNRE function at an increased resolution. For that, we utilized previously described mutant SMyHC III promoter constructs (Wang et al., 1996, 1998) and introduced novel site-directed dinucleotide substitution mutants of individual Hexads in the SMyHC III promoter. Actually, the 72-bp construct is not a 72-bp construct. It is a 5’ deletion construct that removed 72 bp from the 840 bp wild type SMyHC III construct, transforming it into a 768-bp SMyHC III promoter construct. Any directional changes observed in cardiac expression by the 768 bp as compared to the wild type promoter was interpreted in the context as missing regulators present in this 5’ 72 bp.

Wang et al., 1996 and 1998 had already shown that Hexads A and B contained a functional VDRE/RARE, which acted as a ventricular repressor. Using the 768-bp SMyHC III promoter in mouse transgenic lines was thus a natural investigation step for us to evaluate whether regulation of the SMyHC III promoter in the mouse was similar in mice as compared to quail cardiac cultures. As shown in the manuscript, deletion of the 72 bp resulted in the release of a low level of expression in ventricles, consistent with the removal of a ventricular repressor (already described by Wang et al., 1996). It also showed a marked reduction in atrial transgene stimulation, suggesting the elimination of a very important atrial activator.

In 1996, Wang and colleagues mapped an atrial activator to the sequence interval of 160 bp, between -840 and -680 bp (Wang et al., 1996). In our mouse transgenics, we reduced this interval to a mere 72 bp, between -840 to -768 bp. This was very useful information. Wang et al., 1998 showed that HF-1a, M-CAT, and E-box sites located between -840 and -808 bp did not influence atrial expression, so now we had a potential interval of only 40 bp between -808 and -768 bp. Further, our transgenic mice indicated that the GATA site located 3’ from Hexads A, B, and C (GATA site changed to a Sal I site at positions -749 to -743 bp) did not work as a general activator, as in the quail. Thus, the only good candidate for the atrial activator in mice inside the 40-bp fragment between -808 and -768 bp was the cNRE, with its three Hexads, A, B and the novel Hexad C. Because Hexads A plus B composed a functional VDRE/RARE that played a role in ventricular repression in the quail, we hypothesized that the atrial activator would be present in Hexad C. We then mutated the two first purines in Hexad C (the most important ones for nuclear receptor binding, please refer to Umesono et al., Cell, 1991 65: 1255-1266 for a review; Mader et al., J Biol Chem, 1993 268:591-600 for a mutation study; Rastinejad et al., EMBO J., 2000 19:1045-1054 for a crystallographic study as well as additional references listed below) and performed the experiments that demonstrated a profound reduction in atrial expression in the mouse context, revealing the long-sought atrial activator.

Mader, S., Chen, J. Y., Chen, Z., White, J., Chambon, P., and Gronemeyer, H. (1993). The patterns of binding of RAR, RXR and TR homo- and heterodimers to direct repeats are dictated by the binding specificites of the DNA binding domains. EMBO J. 12, 50295041.

Ribeiro, R. C., Apriletti, J. W., Yen, P.M., Chin, W. W., and Baxter, J. D. (1994). Heterodimerization and deoxyribonucleic acid-binding properties of a retinoid X receptor-related factor. Endocrinology.135, 2076-2085.

Wang, G. F., Nikovits, W., Schleinitz, M., and Stockdale, F. E. (1996). Atrial chamber-specific expression of the slow myosin heavy chain 3 gene in the embryonic heart. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 19836-19845.

Wang, G. F., Nikovits, W. Jr., Schleinitz, M., and Stockdale, F. E. (1998). A positive GATA element and a negative vitamin D receptorlike element control atrial chamber-specific expression of a slow myosin heavy-chain gene during cardiac morphogenesis. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 6023-6034.

Zhao, Q., Chasse, S. A., Devarakonda, S., Sierk, M. L., Ahvazi, B., and Rastinejad, F. (2000). Structural basis of RXR-DNA interactions. J. Mol. Biol. 296, 509-520.

Shaffer, P. L. and Gewirth, D. T. (2002). Structural basis of VDR-DNA interactions on direct repeat response elements. EMBO J. 21, 2242-2252.

- Is the cNRE really "necessary and sufficient"? I define necessary and sufficient in this context as a regulatory element that fully recapitulates the expression of the target gene, so if the cNRE was "necessary and sufficient" to direct the appropriate expression of SMyHC III it should be able to drive expression of a reporter gene solely in the atria. While deletion of the cNRE does reduce expression of the reporter gene in atria it is not completely lost nor converted from atrial to ventricular expression (as I understand the study design would suggest should be the effect), similarly fusion of 5 repeats of the cNRE induces expression of a ventricular gene in the atria but also does not convert expression from ventricle to atria. This doesn't seem to satisfy the requirements of a "necessary and sufficient" condition. Perhaps a discussion of why the expectations for "necessary and sufficient" are not met but are still consistent would be beneficial here.

We agree with your reasoning. Our description of the cNRE was perhaps too strong, and we have toned it down accordingly in the revised manuscript to incorporate a much more equilibrated concept that the cNRE biases cardiac expression towards a model of preferential atrial expression. After these corrections, we believe our novel assertion is justified. We show that in the mouse, removal of the cNRE is followed by a major reduction of atrial expression coupled to the release of a low, but quite clear level of expression in the ventricles, when compared to the transgenic mouse harboring the wild type SMyHC III promoter. Note that, as expected, the relative power of the cNRE to establish preferential atrial expression is higher in the mouse (a mammal) than it is in the zebrafish (a teleost), which is biologically sound, as mammals and avians are closer, phylogenetically, than teleosts and avians. Yet, the direction of change of expression in atria and ventricles was exactly as expected, if a given motif responsible for preferential atrial expression was removed (the cNRE in our case), that is: marked reduction in atrial expression and small (albeit evident) release of ventricular expression. We believe that these directional changes observed in species separated by millions of years of independent evolution constitute very good biological evidence for the role of the cNRE in driving preferential atrial expression.

- The claim that the cNRE is derived from a viral integration is not supported by the data. Specifically, the cNRE has sequence similarity to some viral genomes, but this need not be because of homology and can also be because of chance or convergence. Indeed, the region of the chicken genome with the cNRE does have repetitive elements but these are simple sequence repeats, such as (CTCTATGGGG)n and (ACCCATAGAG)n, and a G-rich low complexity region, rather than viral elements; The same is true for the truly genome. These data indicate that the cNRE is not derived from an endogenous virus but is a repetitive and low complexity region, these regions are expected to occur more frequently than expected for larger and more complex regions which would cause the BLAST E value to decrease and appear "significant”, but this is entirely expected because short alignments can have high E values by chance. (Also note that E values do not indicate statistical significance, rather they are the number of hits one can "expect" to see by chance when searching specific database.)

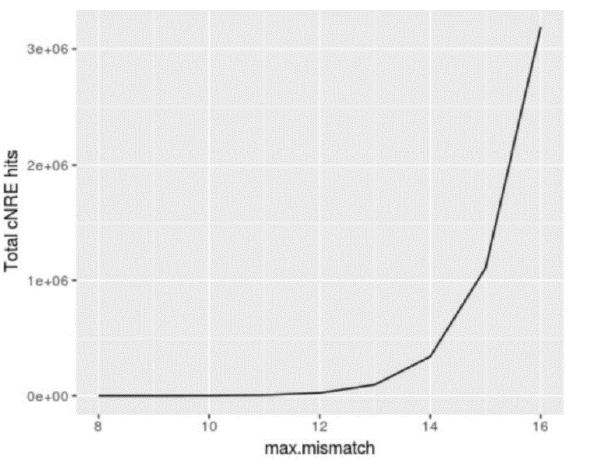

We do understand the criticism, but we would like to advance another concept, based on a series of results that we obtained using bioinformatics-oriented and evolution-oriented analyses. We performed a cNRE scan in the Gallus gallus genome (galGal5), using varying numbers of nucleotide mismatches. When we searched the galGaL5 genome with coordinates matching the localization of cNREs obtained using matchPattern with up to 8 mismatches, only thirty-one (31) and thirty-four (34) hits were found in the 5’ and 3’ strands, respectively. This indicates that a cNRE match is a rather uncommon finding in the Gallus gallus genome.

A more systematic profiling of genome occurrence versus nucleotide mismatch indicated that a significant upward inflexion in the relationship between number of cNRE hits and divergence from the original cNRE version (Coturnix coturnix) is recorded only at 12 mismatches or greater. At 8 mismatches, the total number of cNREs on each DNA strand varied little among all avian species examined, remaining close to the average (31+/- 2,2 cNREs for the 5’ strand, range 1748; 34 +/- 3,3 for the 3’ strand, range 14-64). Consistent with the idea that the cNRE is a specific regulatory motif, rather than an abundant, low complexity sequence, there are only two cNRE occurrences in chromosome 19, which harbors AMHC1, the Gallus gallus ortholog of the Coturnix coturnix SMyHC III gene.

Figure 1: Number of cNRE hits to galGal5 according to maximum mismatches allowed: the cNRE is not an abundant low complexity sequence, but rather a rare repetitive sequence with a clear cutoff level of mismatches allowed. Consistent with this, there are only two (2) cNRE sequences in chromosome 19, the chromosome that contains the AMHC1 gene (the chicken ortholog of the quail SMyHC III gene). ## [1] chr19 [16510, 16541] * | 5’-CAAGGACAAAGAGGGGACAAAGAGGCGGAGGT-3 ## [2] chr19 [32821, 32852] * ‘5’-CAAGGACAAAGAGTGGACAAAGAGGCAGACGT-3

In the evolutionary strategy, which we now include, we first mapped the phylogenetic origins of the SMyHC III family of slow myosins and then established how and when the cNREs became topologically associated with the SMyHC III gene. To do that we repeat masked all available sequences from avian SMyHC III orthologs. As it will become clear below, the cNRE is a rare sequence, rather than a low complexity repeat. Our search for cNREs outside of the quail context (Coturnix coturnix) followed two independent lines. First, we took a scaled, evolution-oriented approach. Initially, we looked for cNREs in species close to the quail (i.e., Galliformes) and then progressively farther, to include derived (i.e., Passeriformes) and basal avians (i.e., Paleognaths) as well as external groups such as crocodilians. While pursuing this line of investigation, it became clear that the cNRE was a rare form of repetitive element, which showed a conserved topological relationship with the SMyHC III gene (i.e., cNREs flanked the SMyHC III genes at 5’ and 3’ regions). Using this topological relationship as a character, we determined when it appeared during avian evolution, and then set out to establish the likely origins of this rare repetitive motif. This search for the origins of the cNRE entailed comparisons to databases of repetitive genome elements, until the extreme telomeric nature of the SMyHC III gene became evident. This finding directed us to the fact that the hexad nature of the cNRE is reminiscent of the hexameric character of telomeric direct repeats. Because direct telomeric repeats are exactly featured in the genomes of avian DNA viruses that can infect the germline and integrate into the avian genome (Morissette & Flamand, 2010), we focused our search for the cNRE on the members of the subfamily Alphaherpesvirinae. In this search, we utilized the human herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV1) as a general model for herpes viruses and a set of four (4) members of the Alphaherpesvirinae family that specifically infect Galliformes (i.e., GaHV1, the virus responsible for avian infectious laryngotracheitis in chickens, GaHV2, the Marek’s disease virus, GaHV3, a non-pathogenic virus and MeHV1, the non-pathogenic Meleagrid herpesvirus 1 capable of infecting chicken and wild turkey) (Waidner et al., 2009). The search for cNREs in Alphaherpesvirinae was successful. We found six (6) cNRE hits in HSV1 and one (1) cNRE was detected in GaHV1, but none in MeHV1, GaHV2, and GaHV3.

Our evolution-directed approach thus led to the direct recognition that cNREs up to a cutoff mismatch value of 11 can be found in the genomes of a family of viruses that contain members that infect avians and integrate their double-stranded DNA into the host germline. Therefore, as a second independent approach, we set out to extend this proof of concept by broadening our search to all known sequenced viruses to perform an unbiased, internally consistent, and quantitative analysis of cNRE presence in viral genomes, as already reported in the initial submission of this manuscript.

-

Evaluation Summary:

In this manuscript Nunes Santos et al. use a combination of computation and experimental methods to identify and characterize a cis-regulatory element that mediates expression of the quail Slow Myosin Heavy Chain III (SMyHC III) gene in the heart. The study contributes to our understanding of how genes can be expressed differentially in the atrial and ventricular chambers of the heart. The evidence for the newly-identified gene regulatory sequence, and its origin, in exclusively directing these gene expression differences could be stronger. This study is of potential interest to readers in the fields of developmental biology, evolution, gene regulation, and biology of repeats.

(This preprint has been reviewed by eLife. We include the public reviews from the reviewers here; the authors also receive private feedback …

Evaluation Summary:

In this manuscript Nunes Santos et al. use a combination of computation and experimental methods to identify and characterize a cis-regulatory element that mediates expression of the quail Slow Myosin Heavy Chain III (SMyHC III) gene in the heart. The study contributes to our understanding of how genes can be expressed differentially in the atrial and ventricular chambers of the heart. The evidence for the newly-identified gene regulatory sequence, and its origin, in exclusively directing these gene expression differences could be stronger. This study is of potential interest to readers in the fields of developmental biology, evolution, gene regulation, and biology of repeats.

(This preprint has been reviewed by eLife. We include the public reviews from the reviewers here; the authors also receive private feedback with suggested changes to the manuscript. Reviewer #3 agreed to share their name with the authors.)

-

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The authors reveal dual regulatory activity of the complex nuclear receptor element (cNRE; contains hexads A+B+C) in cardiac chambers and its evolutionary origin using computational and molecular approaches. Building upon a previous observation that hexads A and B act as ventricular repressor sequences, in this study the authors identify a novel hexad C sequence with preferential atrial expression. The authors also reveal that the cNRE emerged from an endogenous viral element using comparative genomic approaches. The strength of this study is in a combination of in silico evolutionary analyses with in vivo transgenic assays in both zebrafish and mouse models. Rapid, transient expression assays in zebrafish together with assays using stable, transgenic mice demonstrate dual functionality of cNRE depending on …

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The authors reveal dual regulatory activity of the complex nuclear receptor element (cNRE; contains hexads A+B+C) in cardiac chambers and its evolutionary origin using computational and molecular approaches. Building upon a previous observation that hexads A and B act as ventricular repressor sequences, in this study the authors identify a novel hexad C sequence with preferential atrial expression. The authors also reveal that the cNRE emerged from an endogenous viral element using comparative genomic approaches. The strength of this study is in a combination of in silico evolutionary analyses with in vivo transgenic assays in both zebrafish and mouse models. Rapid, transient expression assays in zebrafish together with assays using stable, transgenic mice demonstrate dual functionality of cNRE depending on the chamber context. This is especially intriguing given that the cNRE is present only in Galliformes and has originated likely through viral infection. Interestingly, there seem to be some species-specific differences between zebrafish and mouse models in expression response to mutations within the cNRE. Taken together, these findings bear significant implications for our understanding of dual regulatory elements in the evolutionary context of organ formation.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Nunes Santos et al. investigated the gene regulatory activity of the promoter of the quail myosin gene, SMyHC III, that is expressed specifically in the atria of the heart in quails. To do so, they computationally identified a novel 6-bp sequence within the promoter that is putatively bound by a nuclear receptor transcription factor, and hence is a putative regulatory sequence. They tested this sequence for regulatory activity using transgenic assays in zebrafish and mice, and subjected this sequence to mutagenesis to investigate whether gene regulatory effects are abrogated. They define this sequence, together with two additional known 6-bp regulatory sequences, as a novel regulatory sequence (denoted cNRE) necessary and sufficient for driving atrial-specific expression of SMyHC III. This cNRE sequence is …

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Nunes Santos et al. investigated the gene regulatory activity of the promoter of the quail myosin gene, SMyHC III, that is expressed specifically in the atria of the heart in quails. To do so, they computationally identified a novel 6-bp sequence within the promoter that is putatively bound by a nuclear receptor transcription factor, and hence is a putative regulatory sequence. They tested this sequence for regulatory activity using transgenic assays in zebrafish and mice, and subjected this sequence to mutagenesis to investigate whether gene regulatory effects are abrogated. They define this sequence, together with two additional known 6-bp regulatory sequences, as a novel regulatory sequence (denoted cNRE) necessary and sufficient for driving atrial-specific expression of SMyHC III. This cNRE sequence is shared across several galliform species but appears to be absent in other avian species. The authors find that there is sequence homology between the cNRE and several virus genomes, and they conclude that this regulatory sequence arose in the quail genome by viral integration.

Strengths:

The evolutionary origins of gene regulatory sequences and their impact on directing tissue-specific expression are of great interest to geneticists and evolutionary biologists. The authors of this paper attempt to bring this evolutionary perspective to the developmental biology question of how genes are differentially expressed in different chambers of the heart. The authors test for regulatory activity of the putative regulatory sequence they identified computationally in both zebrafish and mouse transgenic assays. The authors disrupt this sequence using deletions and mutagenesis, and introduce a tandem repeat of the sequence to a reporter gene to determine its consequences on chamber activity. These experiments demonstrate that the identified sequence has regulatory activity.Weaknesses:

There are several decisions and assumptions that have been made by the authors, the reasons for which have not been articulated. Firstly, the rationale for the approach is not clear. The study is a follow-up to work previously performed by the authors which identified two 6-bp sequences important for controlling atrial-specific expression of the quail SMyHC III gene. This study appears to be motivated by the fact that these two sequences, bound by nuclear receptors, do not fully direct chamber-specific expression, and therefore this study aims to find additional regulatory sequences. It is assumed that any additional regulatory sequences should also be bound by nuclear receptors, and be 6-bp in length, and therefore the authors search for 6-bp sequences bound by nuclear receptors. It is not clear what the input sequence for this analysis was. The methods section mentions the cNRE sequence, but this is their newly defined regulatory sequence based on the newly identified 6-bp sequence. It is therefore unclear why Hexad C was identified to be of interest, and not the GATA binding site for example, and whether other sequences in the promoter might have stronger effects on driving atrial-specific expression. Indeed, the zebrafish transgenic assays use the 32 bp cNRE, while in the mouse transgenic assays, a 72 bp region is used. This choice of sequence length is not justified. The decisions about which bases to mutate in the three hexads are also not clear. Why are the first two bases mutated in Hexad B and C and the whole region mutated in Hexad A? Is there a reason to believe these bases are particularly important? The control mutant also has effects on the chamber distribution of GFP expression.Two claims in the paper have weak evidence. Firstly, the conclusion that the cNRE is necessary and sufficient for driving preferential expression in the atrium. Deleting the cNRE does reduce the amount of atrial reporter gene expression but there is not a "conversion" from atrial to ventricular expression as mentioned in line 205. Similarly, a fusion of 5 tandem repeats of the cNRE can induce expression of a ventricular gene in the atria (I'm assuming a single copy is insufficient), but does not abolish ventricular expression. Secondly, the authors claim that the cNRE regulatory sequence arose from viral integration into the genomes of galliform species. While this is an attractive mechanism for explaining novel regulatory sequences, the evidence for this is based purely on sequence homology to viral genomes. And this single observation is not robust as the significance of the sequence matches does not appear to be adjusted for sequence matches expected by chance. The "evolutionary pathway" leading to the direction of chamber-specific expression in the heart as highlighted in the abstract has therefore not been demonstrated.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Summary:

In this manuscript Nunes Santos et al. use a combination of computation and experimental methods to identify and characterize a cis-regulatory element that mediates expression of the quail Slow Myosin Heavy Chain III (SMyHC III) gene in the heart (specifically in the atria). Previous studies had identified a cis-regulatory element that can drive expression of SMyHC III in the heart, but not specifically (solely) in the atria, suggesting additional regulatory elements are responsible for the specific expression of SMyHC III in the atria as opposed to other elements of the heart. To identify these elements Nunes Santos et al. first used a bioinformatic approach to identify potentially functional nuclear receptor binding sites ("Hexads") in the SMyHC III promoter; previous studies had already shown …Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Summary:

In this manuscript Nunes Santos et al. use a combination of computation and experimental methods to identify and characterize a cis-regulatory element that mediates expression of the quail Slow Myosin Heavy Chain III (SMyHC III) gene in the heart (specifically in the atria). Previous studies had identified a cis-regulatory element that can drive expression of SMyHC III in the heart, but not specifically (solely) in the atria, suggesting additional regulatory elements are responsible for the specific expression of SMyHC III in the atria as opposed to other elements of the heart. To identify these elements Nunes Santos et al. first used a bioinformatic approach to identify potentially functional nuclear receptor binding sites ("Hexads") in the SMyHC III promoter; previous studies had already shown that two of these Hexads are important for SMyHC III promoter function. They identified a previously unknown third Hexad within the promoter, and propose that the combination of these three (called the complex Nuclear Receptor Element or cNRE) is necessary and sufficient for specific atrial expression of SMyHC III. Next, they use experimental methods to functionally characterize the cNRE including showing that the quail SMyHC III promoter can drive green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression the atrium of developing zebrafish embryos and that the cNRE is necessary to drive the expression of the human alkaline phosphatase reporter gene (HAP) in transgenic mouse atria. Additional experiments show that the cNRE is portable regulatory element that can drive atrial expression and demonstrate the importance of the three Hexad parts. These data demonstrating that the cNRE mediates atrial-specific expression is well-done and convincing. The authors also note the possibility that the cNRE might be derived from an endogenous viral element but further data are needed to support the hypothesis that the cNRE is of viral origin.Strengths:

- The experimental work demonstrating that the cNRE is a regulatory element that can mediate the atrial-specific expression of SMyHC III.

Weaknesses:

Justification for use of different regulatory elements in the zebrafish (32 bp cNRE) and the mouse transgenic assays (72 bp cNRE), and discussion of the impact of this difference on the results/interpretation.

Is the cNRE really "necessary and sufficient"? I define necessary and sufficient in this context as a regulatory element that fully recapitulates the expression of the target gene, so if the cNRE was "necessary and sufficient" to direct the appropriate expression of SMyHC III it should be able to drive expression of a reporter gene solely in the atria. While deletion of the cNRE does reduce expression of the reporter gene in atria it is not completely lost nor converted from atrial to ventricular expression (as I understand the study design would suggest should be the effect), similarly fusion of 5 repeats of the cNRE induces expression of a ventricular gene in the atria but also does not convert expression from ventricle to atria. This doesn't seem to satisfy the requirements of a "necessary and sufficient" condition. Perhaps a discussion of why the expectations for "necessary and sufficient" are not met but are still consistent would be beneficial here.

The claim that the cNRE is derived from a viral integration is not supported by the data. Specifically, the cNRE has sequence similarity to some viral genomes, but this need not be because of homology and can also be because of chance or convergence. Indeed, the region of the chicken genome with the cNRE does have repetitive elements but these are simple sequence repeats, such as (CTCTATGGGG)n and (ACCCATAGAG)n, and a G-rich low complexity region, rather than viral elements; The same is true for the truly genome. These data indicate that the cNRE is not derived from a endogenous virus but is a repetitive and low complexity region, these regions are expected to occur more frequently than expected for larger and more complex regions which would cause the BLAST E value to decrease and appear "significant" but this is entirely expected because short alignments can have high E values by chance. (Also note that E values do not indicate statistical significance, rather they are the number of hits one can "expect" to see by chance when searching specific database.)

-