Neuropsychological evidence of multi-domain network hubs in the human thalamus

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

Evaluation Summary:

Hwang et al. address the important question about whether specific thalamic sub-regions serve as essential "hubs" for interconnecting diverse cognitive processes. Using a group of patients with isolated thalamic lesions (n=20), and a group of size-matched lesions outside the thalamus (n=42), they report that lesions to the anterior-medio-dorsal thalamus are most likely to cause widespread cognitive deficit. Evidence from existing task-based and resting-state fMRI data sets, as well as data sets on gene expression further provide evidence the importance of these regions as a network hub for domain general cognitive functions.

(This preprint has been reviewed by eLife. We include the public reviews from the reviewers here; the authors also receive private feedback with suggested changes to the manuscript. Reviewer #2 agreed to share their name with the authors.)

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

Hubs in the human brain support behaviors that arise from brain network interactions. Previous studies have identified hub regions in the human thalamus that are connected with multiple functional networks. However, the behavioral significance of thalamic hubs has yet to be established. Our framework predicts that thalamic subregions with strong hub properties are broadly involved in functions across multiple cognitive domains. To test this prediction, we studied human patients with focal thalamic lesions in conjunction with network analyses of the human thalamocortical functional connectome. In support of our prediction, lesions to thalamic subregions with stronger hub properties were associated with widespread deficits in executive, language, and memory functions, whereas lesions to thalamic subregions with weaker hub properties were associated with more limited deficits. These results highlight how a large-scale network model can broaden our understanding of thalamic function for human cognition.

Article activity feed

-

-

Author Response:

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

This manuscript was well written and interrogates an exciting and important question about whether thalamic sub-regions serve as essential "hubs" for interconnecting diverse cognitive processes. This lesion dataset, combined with normative imaging analyses, serves as a fairly unique and powerful way to address this question.

Overall, I found the data analysis and processing to be appropriate. I have a few additional questions that remain to be answered to strengthen the conclusions of the authors.

- The number of cases of thalamic lesions was small (20 participants) and the sites of overlap in this group is at maximum 5 cases. Finding focal thalamic lesions with the appropriate characteristics is likely to be relatively hard, so this smaller sample size is not surprising, but it …

Author Response:

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

This manuscript was well written and interrogates an exciting and important question about whether thalamic sub-regions serve as essential "hubs" for interconnecting diverse cognitive processes. This lesion dataset, combined with normative imaging analyses, serves as a fairly unique and powerful way to address this question.

Overall, I found the data analysis and processing to be appropriate. I have a few additional questions that remain to be answered to strengthen the conclusions of the authors.

- The number of cases of thalamic lesions was small (20 participants) and the sites of overlap in this group is at maximum 5 cases. Finding focal thalamic lesions with the appropriate characteristics is likely to be relatively hard, so this smaller sample size is not surprising, but it suggests that the overlap analyses conducted to identify "multi-domain" hub sites will be relatively underpowered. Given these considerations, I was a bit surprised that the authors did not start with a more hypothesis driven approach (i.e., separating the groups into those with damage to hubs vs. non-hubs) rather than using this more exploratory overlap analysis. It is particularly concerning that the primary "multi-domain" overlap site is also the primary site of overlap in general across thalamic lesion cases (Fig. 2A).

An issue that arises when attempting to separate lesions into “hub” versus “non-hub” lesions at the study onset is there is not an accepted definition or threshold for a binary categorization of hubs. The primary metric for estimating hub property, participation coefficient (PC), is a continuous measure ranging from 0 to 1, without an objective threshold to differentiate hub versus non-hub regions. Thus, a binary classification would require exploring an arbitrary threshold for splitting our sample. Our concern is that assigning an arbitrary threshold and delineating groups based on that threshold would be equally, if not more, exploratory. However, we appreciate this comment and future studies may be able to use the results of the current analysis to formulate an a priori threshold based on our current results. Similarly, given the relative difficulty recruiting patients with focal thalamic lesions, we did not have enough power to do a linear regression testing the relationship between PC and the global deficit score. Weighing all these factors, we determined that counting the number of tests impaired, and defining global deficit as more than one domain impaired, is a more objective and less exploratory approach for addressing our specific hypotheses than arbitrarily splitting PC values.

We agree with the reviewer that our unequal lesion coverage in the thalamus is a limitation. We have acknowledged this in the discussion section (line 561). There may very likely be other integrative sites (for example the medial pulvinar) that we missed simply because we did not have sufficient lesion coverage. We have updated our discussion section (line 561) to more explicitly discuss the limitation of our study.

- Many of the comparison lesion sites (Fig. 1A) appear to target white matter rather than grey matter locations. Given that white matter damage may have systematically different consequences as grey matter damage, it may be important to control for these characteristics.

We have conducted further analyses to better control for the effects of white matter damage.

- The use of cortical lesion locations as generic controls was a bit puzzling to me, as there are hub locations in the cortex as well as in the thalamus. It would be useful to determine whether hub locations in the cortex and thalamus show similar properties, and that an overlap approach such as the one utilized here, is effective at identifying hubs in the cortex given the larger size of this group.

We have conducted additional analyses to replicate our findings and validate our approach in a group of 145 expanded comparison patients. We found that comparison patients with lesions to brain regions with higher PC values exhibited more global deficits, when compared to patients that did not exhibit global deficits. Results from this additional analysis were included in Figure 6.

- While I think the current findings are very intriguing, I think the results would be further strengthened if the authors were able to confirm: (1) that the multi-domain thalamic lesions are not more likely to impact multiple nuclei or borders between nuclei (this could also lead to a multi-domain profile of results) and (2) that the locations of these locations are consistent in their network functions across individuals (perhaps through comparisons with Greene et al., 2020 or more extended analyses of the datasets included in this work) as this would strengthen the connection between the individual lesion cases and the normative sample analyses.

We can confirm that multi-domain thalamic lesions did not cover more thalamic subdivisions (anatomical nuclei or functional parcellations). We also examined whether the multi-domain lesion site consistently showed high PC values in individual normative subjects. We calculated thalamic PC values for each of the 235 normative subjects, and compared the average PC values in the multi-domain lesion site versus the single domain-lesion site across these normative subjects. We found the multi-domain site exhibited significantly higher PC values (Figure 5D, t(234) = 6.472, p < 0.001). This suggest that the multi-domain lesion site consistently showed stronger connector hub property across individual normative subjects.

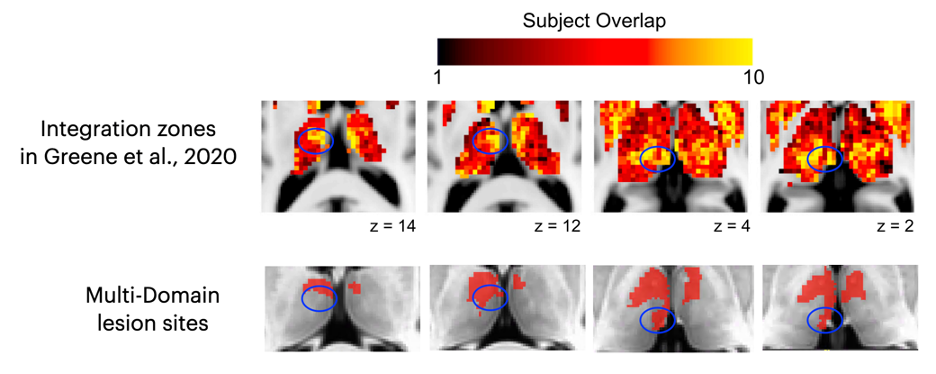

We also visually compared our results with Greene et al., 2020 (see below). We found that in the dorsal thalamus (z >10), there was a good spatial overlap between the integration zone reported in Greene et al 2020 and the multi-domain lesion site that we identified. In the ventral thalamus (z < 4), we did not identify the posterior thalamus as part of the multi-domain lesion site, likely because we did not have sufficient lesion coverage in the posterior thalamus.

In terms of describing the putative network functions of the thalamic lesion sites, results presented in Figure 7A indicate that multi-domain lesion sites in the thalamus were broadly coupled with cortical functional networks previously implicated in domain-general control processes, such as the cingulo-opercular network, the fronto-parietal network, and the dorsal attention network.

Greene, Deanna J., et al. "Integrative and network-specific connectivity of the basal ganglia and thalamus defined in individuals." Neuron 105.4 (2020): 742-758.

-

Evaluation Summary:

Hwang et al. address the important question about whether specific thalamic sub-regions serve as essential "hubs" for interconnecting diverse cognitive processes. Using a group of patients with isolated thalamic lesions (n=20), and a group of size-matched lesions outside the thalamus (n=42), they report that lesions to the anterior-medio-dorsal thalamus are most likely to cause widespread cognitive deficit. Evidence from existing task-based and resting-state fMRI data sets, as well as data sets on gene expression further provide evidence the importance of these regions as a network hub for domain general cognitive functions.

(This preprint has been reviewed by eLife. We include the public reviews from the reviewers here; the authors also receive private feedback with suggested changes to the manuscript. Reviewer #2 …

Evaluation Summary:

Hwang et al. address the important question about whether specific thalamic sub-regions serve as essential "hubs" for interconnecting diverse cognitive processes. Using a group of patients with isolated thalamic lesions (n=20), and a group of size-matched lesions outside the thalamus (n=42), they report that lesions to the anterior-medio-dorsal thalamus are most likely to cause widespread cognitive deficit. Evidence from existing task-based and resting-state fMRI data sets, as well as data sets on gene expression further provide evidence the importance of these regions as a network hub for domain general cognitive functions.

(This preprint has been reviewed by eLife. We include the public reviews from the reviewers here; the authors also receive private feedback with suggested changes to the manuscript. Reviewer #2 agreed to share their name with the authors.)

-

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

This manuscript was well written and interrogates an exciting and important question about whether thalamic sub-regions serve as essential "hubs" for interconnecting diverse cognitive processes. This lesion dataset, combined with normative imaging analyses, serves as a fairly unique and powerful way to address this question.

Overall, I found the data analysis and processing to be appropriate. I have a few additional questions that remain to be answered to strengthen the conclusions of the authors.

1. The number of cases of thalamic lesions was small (20 participants) and the sites of overlap in this group is at maximum 5 cases. Finding focal thalamic lesions with the appropriate characteristics is likely to be relatively hard, so this smaller sample size is not surprising, but it suggests that the overlap …

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

This manuscript was well written and interrogates an exciting and important question about whether thalamic sub-regions serve as essential "hubs" for interconnecting diverse cognitive processes. This lesion dataset, combined with normative imaging analyses, serves as a fairly unique and powerful way to address this question.

Overall, I found the data analysis and processing to be appropriate. I have a few additional questions that remain to be answered to strengthen the conclusions of the authors.

1. The number of cases of thalamic lesions was small (20 participants) and the sites of overlap in this group is at maximum 5 cases. Finding focal thalamic lesions with the appropriate characteristics is likely to be relatively hard, so this smaller sample size is not surprising, but it suggests that the overlap analyses conducted to identify "multi-domain" hub sites will be relatively underpowered. Given these considerations, I was a bit surprised that the authors did not start with a more hypothesis driven approach (i.e., separating the groups into those with damage to hubs vs. non-hubs) rather than using this more exploratory overlap analysis. It is particularly concerning that the primary "multi-domain" overlap site is also the primary site of overlap in general across thalamic lesion cases (Fig. 2A).

2. Many of the comparison lesion sites (Fig. 1A) appear to target white matter rather than grey matter locations. Given that white matter damage may have systematically different consequences as grey matter damage, it may be important to control for these characteristics.

3. The use of cortical lesion locations as generic controls was a bit puzzling to me, as there are hub locations in the cortex as well as in the thalamus. It would be useful to determine whether hub locations in the cortex and thalamus show similar properties, and that an overlap approach such as the one utilized here, is effective at identifying hubs in the cortex given the larger size of this group.

4. While I think the current findings are very intriguing, I think the results would be further strengthened if the authors were able to confirm: (1) that the multi-domain thalamic lesions are not more likely to impact multiple nuclei or borders between nuclei (this could also lead to a multi-domain profile of results) and (2) that the locations of these locations are consistent in their network functions across individuals (perhaps through comparisons with Greene et al., 2020 or more extended analyses of the datasets included in this work) as this would strengthen the connection between the individual lesion cases and the normative sample analyses.

Greene, Deanna J., et al. "Integrative and network-specific connectivity of the basal ganglia and thalamus defined in individuals." Neuron 105.4 (2020): 742-758.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Hwang et al. compared the neuropsychological deficits due to isolated thalamic lesions (n=20), to size-matched lesions outside the thalamus (n=42), which revealed significantly greater likelihood of domain-general deficits due to thalamic lesions. They found the left anterior-medio-dorsal thalamus to be the most likely lesion site to cause widespread cognitive deficits, highlighting its importance as a network hub. Drawing on their large patient database, Hwang et al. were able to verify this finding by also comparing to a larger sample (n=320) of non-size-matched control lesion patients. They utilized the NeuroSynth task fMRI database to show that their lesion-cognitive deficit mapping results were less likely to be due to thalamic lesions damaging multiple functional networks, and more likely due to the …

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Hwang et al. compared the neuropsychological deficits due to isolated thalamic lesions (n=20), to size-matched lesions outside the thalamus (n=42), which revealed significantly greater likelihood of domain-general deficits due to thalamic lesions. They found the left anterior-medio-dorsal thalamus to be the most likely lesion site to cause widespread cognitive deficits, highlighting its importance as a network hub. Drawing on their large patient database, Hwang et al. were able to verify this finding by also comparing to a larger sample (n=320) of non-size-matched control lesion patients. They utilized the NeuroSynth task fMRI database to show that their lesion-cognitive deficit mapping results were less likely to be due to thalamic lesions damaging multiple functional networks, and more likely due to the thalamus in general and the anterior-medio-dorsal thalamus in particular serving as a network hub. They then analyzed resting state functional connectivity data, which as hypothesized revealed the anterior-medio-dorsal thalamus to have the highest participation coefficient, an indicator of hubness. Finally, they analyzed Allen Brain Atlas data to show that the same segment of the thalamus preferentially expresses CALB1 in comparison to the remainder of the thalamus which expresses more PVALB. This article combines lesion, task fMRI, resting state functional connectivity and gene expression data, all of which strongly point towards the anterio-medio-dorsal thalamus as an integrative hub for cognitive function. This work has implications for making clinical prognoses following thalamic lesions and it strongly suggests that the anterior-medio-dorsal thalamus makes domain general computations to cognition.

-