Neural mechanisms of modulations of empathy and altruism by beliefs of others’ pain

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

Evaluation Summary:

This article represents a series of behavioral and imaging experiments investigating the effect of cognitive manipulation of beliefs on the explicit perception of other individual's pain and altruistic behavior. The results indicate that manipulations of people's beliefs regarding how much another person suffers alters the way participants rate the pain of others as well as the amount of money participants are willing to donate to the other person. Neuroimaging experiments, using EEG and fMRI, show that manipulating beliefs modulates neural activity in an early time window (P2 component) in response to the emotional expression of the other individual, involving temporo-parietal and medial frontal cortices. While there are some potential concerns about the novelty and implication of these findings, the results are overall clear and consistent throughout the six experiments, integrate with existing data, and are of broad interest to the researchers studying the neurobiology of empathy.

(This preprint has been reviewed by eLife. We include the public reviews from the reviewers here; the authors also receive private feedback with suggested changes to the manuscript. The reviewers remained anonymous to the authors.)

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

Perceived cues signaling others’ pain induce empathy which in turn motivates altruistic behavior toward those who appear suffering. This perception-emotion-behavior reactivity is the core of human altruism but does not always occur in real-life situations. Here, by integrating behavioral and multimodal neuroimaging measures, we investigate neural mechanisms underlying modulations of empathy and altruistic behavior by beliefs of others’ pain (BOP). We show evidence that lack of BOP reduces subjective estimation of others’ painful feelings and decreases monetary donations to those who show pain expressions. Moreover, lack of BOP attenuates neural responses to their pain expressions within 200 ms after face onset and modulates neural responses to others’ pain in the insular, post-central, and frontal cortices. Our findings suggest that BOP provide a cognitive basis of human empathy and altruism and unravel the intermediate neural mechanisms.

Article activity feed

-

-

Author Response:

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

[...] The major limitation of the manuscript lies in the framing and interpretation of the results, and therefore the evaluation of novelty. Authors claim for an important and unique role of beliefs-of-other-pain in altruistic behavior and empathy for pain. The problem is that these experiments mainly show that behaviors sometimes associated with empathy-for-pain can be cognitively modulated by changing prior beliefs. To support the notion that effects are indeed relating to pain processing generally or empathy for pain specifically, a similar manipulation, done for instance on beliefs about the happiness of others, before recording behavioural estimation of other people's happiness, should have been performed. If such a belief-about-something-else-than-pain would have led to similar …

Author Response:

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

[...] The major limitation of the manuscript lies in the framing and interpretation of the results, and therefore the evaluation of novelty. Authors claim for an important and unique role of beliefs-of-other-pain in altruistic behavior and empathy for pain. The problem is that these experiments mainly show that behaviors sometimes associated with empathy-for-pain can be cognitively modulated by changing prior beliefs. To support the notion that effects are indeed relating to pain processing generally or empathy for pain specifically, a similar manipulation, done for instance on beliefs about the happiness of others, before recording behavioural estimation of other people's happiness, should have been performed. If such a belief-about-something-else-than-pain would have led to similar results, in terms of behavioural outcome and in terms of TPJ and MFG recapitulating the pattern of behavioral responses, we would know that the results reflect changes of beliefs more generally. Only if the results are specific to a pain-empathy task, would there be evidence to associate the results to pain specifically. But even then, it would remain unclear whether the effects truly relate to empathy for pain, or whether they may reflect other routes of processing pain.

We thank Reviewer #1's for these comments/suggestions regarding the specificity of belief effects on brain activity involved in empathy for pain. Our paper reported 6 behavioral/EEG/fMRI experiments that tested effects of beliefs of others’ pain on empathy and monetary donation (an empathy-related altruistic behavior). We showed not only behavioral but also neuroimaging results that consistently support the hypothesis of the functional role of beliefs of others' pain in modulations of empathy (based on both subjective and objective measures as clarified in the revision) and altruistic behavior. We agree with Reviewer 1# that it is important to address whether the belief effect is specific to neural underpinnings of empathy for pain or is general for neural responses to various facial expressions such as happy, as suggested by Reviewer #1. To address this issue, we conducted an additional EEG experiment (which can be done in a limited time in the current situation), as suggested by Reviewer #1. This new EEG experiment tested (1) whether beliefs of authenticity of others’ happiness influence brain responses to perceived happy expressions; (2) whether beliefs of happiness modulate neural responses to happy expressions in the P2 time window as that characterized effects of beliefs of pain on ERPs.

Our behavioral results in this experiment (as Supplementary Experiment 1 reported in the revision) showed that the participants reported less feelings of happiness when viewing actors who simulate others' smiling compared to when viewing awardees who smile due to winning awards (see the figure below). Our ERP results in Supplementary Experiment 1 further showed that lack of beliefs of authenticity of others’ happiness (e.g., actors simulate others' happy expressions vs. awardees smile and show happy expressions due to winning an award) reduced the amplitudes of a long-latency positive component (i.e., P570) over the frontal region in response to happy expressions. These findings suggest that (1) there are possibly general belief effects on subjective feelings and brain activities in response to facial expressions; (2) beliefs of others' pain or happiness affect neural responses to facial expressions in different time windows after face onset; (3) modulations of the P2 amplitude by beliefs of pain may not be generalized to belief effects on neural responses to any emotional states of others. We reported the results of this new ERP experiment in the revision as Supplementary Experiment 1 and also discussed the issue of specificity of modulations of empathic neural responses by beliefs of others' pain in the revised Discussion (page 49-50).

Supplementary Experiment Figure 1. EEG results of Supplementary Experiment 1. (a) Mean rating scores of happy intensity related to happy and neutral expressions of faces with awardee or actor/actress identities. (b) ERPs to faces with awardee or actor/actress identities at the frontal electrodes. The voltage topography shows the scalp distribution of the P570 amplitude with the maximum over the central/parietal region. (c) Mean differential P570 amplitudes to happy versus neutral expressions of faces with awardee or actor/actress identities. The voltage topographies illustrate the scalp distribution of the P570 difference waves to happy (vs. neutral) expressions of faces with awardee or actor/actress identities, respectively. Shown are group means (large dots), standard deviation (bars), measures of each individual participant (small dots), and distribution (violin shape) in (a) and (c).

Supplementary Experiment Figure 1. EEG results of Supplementary Experiment 1. (a) Mean rating scores of happy intensity related to happy and neutral expressions of faces with awardee or actor/actress identities. (b) ERPs to faces with awardee or actor/actress identities at the frontal electrodes. The voltage topography shows the scalp distribution of the P570 amplitude with the maximum over the central/parietal region. (c) Mean differential P570 amplitudes to happy versus neutral expressions of faces with awardee or actor/actress identities. The voltage topographies illustrate the scalp distribution of the P570 difference waves to happy (vs. neutral) expressions of faces with awardee or actor/actress identities, respectively. Shown are group means (large dots), standard deviation (bars), measures of each individual participant (small dots), and distribution (violin shape) in (a) and (c).In the revised Introduction we cited additional literatures to explain the concept of empathy, behavioral and neuroimaging measures of empathy, and how, similar to previous research, we studied empathy for others' pain using subjective (self reports) and objective (brain responses) estimation of empathy (page 6-7). In particular, we mentioned that subjective estimation of empathy for pain depends on collection of self-reports of others' pain and ones' own painful feelings when viewing others' suffering. Objective estimation of empathy for pain relies on recording of brain activities (using fMRI, EEG, etc.) that differentially respond to painful or non-painful stimuli applied to others. fMRI studies revealed greater activations in the ACC, AI, and sensorimotor cortices in response to painful or non-painful stimuli applied to others. EEG studies showed that event-related potentials (ERPs) in response to perceived painful stimulations applied to others' body parts elicited neural responses that differentiated between painful and neutral stimuli over the frontal region as early as 140 ms after stimulus onset (Fan and Han, 2008; see Coll, 2018 for review). Moreover, the mean ERP amplitudes at 140–180 ms predicted subjective reports of others' pain and ones' own unpleasantness. Particularly related to the current study, previous research showed that pain compared to neutral expressions increased the amplitude of the frontal P2 component at 128–188 ms after stimulus onset (Sheng and Han, 2012; Sheng et al., 2013; 2016; Han et al., 2016; Li and Han, 2019) and the P2 amplitudes in response to others' pain expressions positively predicted subjective feelings of own unpleasantness induced by others' pain and self-report of one's own empathy traits (e.g., Sheng and Han, 2012). These brain imaging findings indicate that brain responses to others' pain can (1) differentiate others' painful or non-painful emotional states to support understanding of others' pain and (2) predict subjective feelings of others' pain and one's own unpleasantness induced by others' pain to support sharing of others' painful feelings. These findings provide effective subjective and objective measures of empathy that were used in the current study to investigate neural mechanisms underlying modulation of empathy and altruism by beliefs of others’ pain.

In addition, we took Reviewer #1’s suggestion for VPS analyses which examined specifically how neural activities in the empathy-related regions identified in the previous research (Krishnan et al., 2016, eLife) were modulated by beliefs of others’ pain. The results (page 40) provide further evidence for our hypothesis. We also reported new results of RSA analyses(page 39) that activities in the brain regions supporting affective sharing (e.g., insula), sensorimotor resonance (e.g., post-central gyrus), and emotion regulation (e.g., lateral frontal cortex) provide intermediate mechanisms underlying modulations of subjective feelings of others' pain intensity due to lack of BOP. We believe that, putting all these results together, our paper provides consistent evidence that empathy and altruistic behavior are modulated by BOP.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

[...] 1. In laying out their hypotheses, the authors write, "The current work tested the hypothesis that BOP provides a fundamental cognitive basis of empathy and altruistic behavior by modulating brain activity in response to others' pain. Specifically, we tested predictions that weakening BOP inhibits altruistic behavior by decreasing empathy and its underlying brain activity whereas enhancing BOP may produce opposite effects on empathy and altruistic behavior." While I'm a little dubious regarding the enhancement effects (see below), a supporting assumption here seems to be that at baseline, we expect that painful expressions reflect real pain experience. To that end, it might be helpful to ground some of the introduction in what we know about the perception of painful expressions (e.g., how rapidly/automatically is pain detected, do we preferentially attend to pain vs. other emotions, etc.).

Thanks for this suggestion! We included additional details about previous findings related to processes of painful expressions in the revised Introduction (page 7-8). Specifically, we introduced fMRI and ERP studies of pain expressions that revealed structures and temporal procedure of neural responses to others' pain (vs. neutral) expressions. Moreover, neural responses to others' pain (vs. neutral) expressions were associated with self-report of others' feelings, indicating functional roles of pain-expression induced brain activities in empathy for pain.

- For me, the key takeaway from this manuscript was that our assessment of and response to painful expressions is contextually-sensitive - specifically, to information reflecting whether or not targets are actually in pain. As the authors state it, "Our behavioral and neuroimaging results revealed critical functional roles of BOP in modulations of the perception-emotion-behavior reactivity by showing how BOP predicted and affected empathy/empathic brain activity and monetary donations. Our findings provide evidence that BOP constitutes a fundamental cognitive basis for empathy and altruistic behavior in humans." In other words, pain might be an incredibly socially salient signal, but it's still easily overridden from the top down provided relevant contextual information - you won't empathize with something that isn't there. While I think this hypothesis is well-supported by the data, it's also backed by a pretty healthy literature on contextual influences on pain judgments (including in clinical contexts) that I think the authors might want to consider referencing (here are just a few that come to mind: Craig et al., 2010; Twigg et al., 2015; Nicolardi et al., 2020; Martel et al., 2008; Riva et al., 2015; Hampton et al., 2018; Prkachin & Rocha, 2010; Cui et al., 2016).

Thanks for this great suggestion! Accordingly, we included an additional paragraph in the revised Discussion regarding how social contexts influence empathy and cited the studies mentioned here (page 46-47).

- I had a few questions regarding the stimuli the authors used across these experiments. First, just to confirm, these targets were posing (e.g., not experiencing) pain, correct? Second, the authors refer to counterbalancing assignment of these stimuli to condition within the various experiments. Was target gender balanced across groups in this counterbalancing scheme? (e.g., in Experiment 1, if 8 targets were revealed to be actors/actresses in Round 2, were 4 female and 4 male?) Third, were these stimuli selected at random from a larger set, or based on specific criteria (e.g., normed ratings of intensity, believability, specificity of expression, etc.?) If so, it would be helpful to provide these details for each experiment.

We'd be happy to clarify these questions. First, photos of faces with pain or neutral expressions were adopted from the previous work (Sheng and Han, 2012). Photos were taken from models who were posing but not experience pain. These photos were taken and selected based on explicit criteria of painful expressions (i.e., brow lowering, orbit tightening, and raising of the upper lip; Prkachin, 1992). In addition, the models' facial expressions were validated in independent samples of participants (see Sheng and Han, 2012). Second, target gender was also balanced across groups in this counterbalancing scheme. We also analyzed empathy rating score and monetary donations related to male and female target faces and did not find any significant gender effect (see our response to Point 5 below). Third, because the face stimuli were adopted from the previous work and the models' facial expressions were validated in independent samples of participants regarding specificity of expression, pain intensity, etc (Sheng and Han, 2012), we did not repeat these validation in our participants. Most importantly, we counterbalanced the stimuli in different conditions so that the stimuli in different conditions (e.g., patient vs. actor/actress conditions) were the same across the participants in each experiment. The design like this excluded any potential confound arising from the stimuli themselves.

- The nature of the charitable donation (particularly in Experiment 1) could be clarified. I couldn't tell if the same charity was being referenced in Rounds 1 and 2, and if there were multiple charities in Round 2 (one for the patients and one for the actors).

Thanks for this comment! Yes, indeed, in both Rounds 1 and 2, the participants were informed that the amount of one of their decisions would be selected randomly and donated to one of the patients through the same charity organization (we clarified these in the revised Method section, page 55-56). We made clear in the revision that after we finished all the experiments of this study, the total amount of the participants' donations were subject to a charity organization to help patients who suffer from the same disease after the study.

- I'm also having a hard time understanding the authors' prediction that targets revealed to truly be patients in the 2nd round will be associated with enhanced BOP/altruism/etc. (as they state it: "By contrast, reconfirming patient identities enhanced the coupling between perceived pain expressions of faces and the painful emotional states of face owners and thus increased BOP.") They aren't in any additional pain than they were before, and at the outset of the task, there was no reason to believe that they weren't suffering from this painful condition - therefore I don't see why a second mention of their pain status should increase empathy/giving/etc. It seems likely that this is a contrast effect driven by the actor/actress targets. See the Recommendations for the Authors for specific suggestions regarding potential control experiments. (I'll note that the enhancement effect in Experiment 2 seems more sensible - here, the participant learns that treatment was ineffective, which may be painful in and of itself.)

Thanks for comments on this important point! Indeed, our results showed that reassuring patient identities in Experiment 1 or by noting the failure of medical treatment related to target faces in Experiment 2 increased rating scores of others' pain and own unpleasantness and prompted more monetary donations to target faces. The increased empathy rating scores and monetary donations might be due to that repeatedly confirming patient identity or knowing the failure of medical treatment increased the belief of authenticity of targets' pain and thus enhanced empathy. However, repeatedly confirming patient identity or knowing the failure of medical treatment might activate other emotional responses to target faces such as pity or helplessness, which might also influence altruistic decisions. We agree with Reviewer #2 that, although our subjective estimation of empathy in Exp. 1 and 2 suggested enhanced empathy in the 2nd_round test, there are alternative interpretations of the results and these should be clarified in future work. We clarified these points in the revised Discussion (page 41-42).

- I noted that in the Methods for Experiment 3, the authors stated "We recruited only male participants to exclude potential effects of gender difference in empathic neural responses." This approach continues through the rest of the studies. This raises a few questions. Are there gender differences in the first two studies (which recruited both male and female participants)? Moreover, are the authors not concerned about target gender effects? (Since, as far as I can tell, all studies use both male and female targets, which would mean that in Experiments 3 and on, half the targets are same-gender as the participants and the other half are other-gender.) Other work suggests that there are indeed effects of target gender on the recognition of painful expressions (Riva et al., 2011).

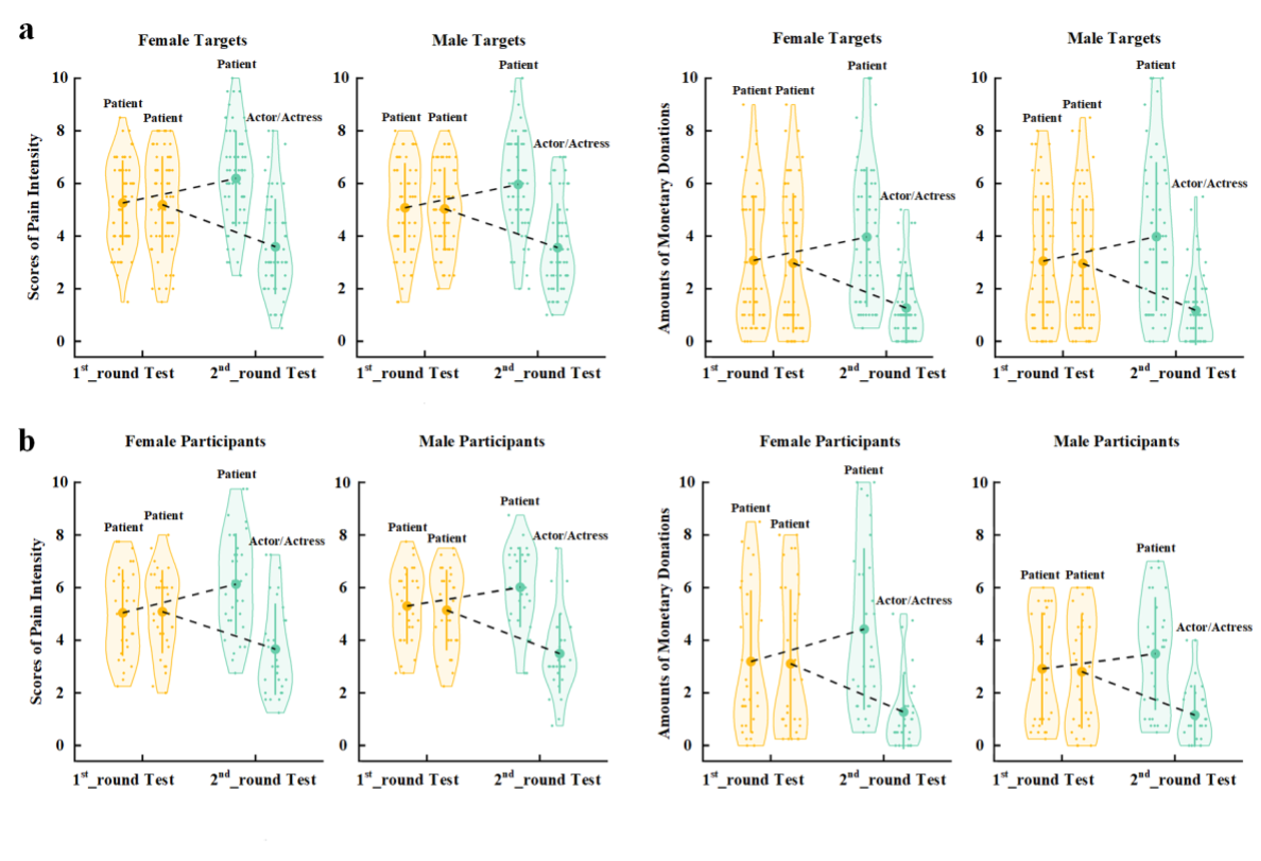

Thanks for raising this interesting question! Therefore, we reanalyzed data in Exp. 1 by including participants' gender or face gender as an independent variable. The three-way ANOVAs of pain intensity scores and amounts of monetary donations with Face Gender (female vs. male targets) × Test Phase (1st vs. 2nd_round) × Belief Change (patient-identity change vs. patient-identity repetition) did not show any significant three-way interaction (F(1,59) = 0.432 and 0.436, p = 0.514 and 0.512, ηp2 = 0.007 and 0.007, 90% CI = (0, 0.079) and (0, 0.079), indicating that face gender do not influence the results (see the figure below). Similarly, the three-way ANOVAs with Participant Gender (female vs. male participants) × Test Phase × Belief Change did not show any significant three-way interaction (F(1,58) = 0.121 and 1.586, p = 0.729 and 0.213, ηp2 = 0.002 and 0.027, 90% CI = (0, 0.055) and (0, 0.124), indicating no reliable difference in empathy and donation between men and women. It seems that the measures of empathy and altruistic behavior in our study were not sensitive to gender of empathy targets and participants' sexes.

Figure legend: (a) Scores of pain intensity and amount of monetary donations are reported separately for male and female target faces. (b) Scores of pain intensity and amount of monetary donations are reported separately for male and female participants.

Figure legend: (a) Scores of pain intensity and amount of monetary donations are reported separately for male and female target faces. (b) Scores of pain intensity and amount of monetary donations are reported separately for male and female participants.- I was a little unclear on the motivation for Experiment 4. The authors state "If BOP rather than other processes was necessary for the modulation of empathic neural responses in Experiment 3, the same manipulation procedure to assign different face identities that do not change BOP should change the P2 amplitudes in response to pain expressions." What "other processes" are they referring to? As far as I could tell, the upshot of this study was just to demonstrate that differences in empathy for pain were not a mere consequence of assignment to social groups (e.g., the groups must have some relevance for pain experience). While the data are clear and as predicted, I'm not sure this was an alternate hypothesis that I would have suggested or that needs disconfirming.

Thanks for this comment! We feel sorry for not being able to make clear the research question in Exp. 4. In the revised Results section (page 27-28) we clarified that the learning and EEG recording procedures in Experiment 3 consisted of multiple processes, including learning, memory, identity recognition, assignment to social groups, etc. The results of Experiment 3 left an open question of whether these processes, even without BOP changes induced through these processes, would be sufficient to result in modulation of the P2 amplitude in response to pain (vs. neutral) expressions of faces with different identities. In Experiment 4 we addressed this issue using the same learning and identity recognition procedures as those in Experiment 3 except that the participants in Experiment 4 had to learn and recognize identities of faces of two baseball teams and that there is no prior difference in BOP associated with faces of beliefs of the two baseball teams. If the processes involved in the learn and reorganization procedures rather than the difference in BOP were sufficient for modulation of the P2 amplitude in response to pain (vs. neutral) expressions of faces, we would expect similar P2 modulations in Experiments 4 and 3. Otherwise, the difference in BOP produced during the learning procedure was necessary for the modulation of empathic neural responses, we would not expect modulations of the P2 amplitude in response to pain (vs. neutral) expressions in Experiment 4. We believe that the goal and rationale of Exp. 4 are clear now.

-

Evaluation Summary:

This article represents a series of behavioral and imaging experiments investigating the effect of cognitive manipulation of beliefs on the explicit perception of other individual's pain and altruistic behavior. The results indicate that manipulations of people's beliefs regarding how much another person suffers alters the way participants rate the pain of others as well as the amount of money participants are willing to donate to the other person. Neuroimaging experiments, using EEG and fMRI, show that manipulating beliefs modulates neural activity in an early time window (P2 component) in response to the emotional expression of the other individual, involving temporo-parietal and medial frontal cortices. While there are some potential concerns about the novelty and implication of these findings, the results are …

Evaluation Summary:

This article represents a series of behavioral and imaging experiments investigating the effect of cognitive manipulation of beliefs on the explicit perception of other individual's pain and altruistic behavior. The results indicate that manipulations of people's beliefs regarding how much another person suffers alters the way participants rate the pain of others as well as the amount of money participants are willing to donate to the other person. Neuroimaging experiments, using EEG and fMRI, show that manipulating beliefs modulates neural activity in an early time window (P2 component) in response to the emotional expression of the other individual, involving temporo-parietal and medial frontal cortices. While there are some potential concerns about the novelty and implication of these findings, the results are overall clear and consistent throughout the six experiments, integrate with existing data, and are of broad interest to the researchers studying the neurobiology of empathy.

(This preprint has been reviewed by eLife. We include the public reviews from the reviewers here; the authors also receive private feedback with suggested changes to the manuscript. The reviewers remained anonymous to the authors.)

-

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The authors investigate the effect of manipulating participant's beliefs about how much pain another individual is really experiencing, on participants' explicit rating of the other's pain, and on participants' willingness to donate money to the suffering person. Towards their aim, the authors designed and collected the results of 6 experiments, that collected behavioral and imaging data (EEG and fMRI). Authors manipulated the beliefs of how much pain the other should be in, by altering participants beliefs about the identity of the person shown in the presented pictures: in the majority of the experiments participants believed to watch facial expressions either collected from a suffering patient or an actor mimicking the patient's facial expression. Participants were then asked to rate how much pain the …

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The authors investigate the effect of manipulating participant's beliefs about how much pain another individual is really experiencing, on participants' explicit rating of the other's pain, and on participants' willingness to donate money to the suffering person. Towards their aim, the authors designed and collected the results of 6 experiments, that collected behavioral and imaging data (EEG and fMRI). Authors manipulated the beliefs of how much pain the other should be in, by altering participants beliefs about the identity of the person shown in the presented pictures: in the majority of the experiments participants believed to watch facial expressions either collected from a suffering patient or an actor mimicking the patient's facial expression. Participants were then asked to rate how much pain the person in the picture felt, how much unpleasantness the participants themself felt while watching the pictures, and how much money participants are willing to donate to one of the suffering people in the pictures.

A major strength of the paper is the introduction of slightly different modification to the paradigm across the six studies, which allowed them to reliably replicate the effect of their manipulation on participant's behavior; to identify whether the believes-manipulation mediated participant's behavior and brain activity; to touch upon the time at which the manipulation acts on brain activity; and finally to identify the network that is modulated by the manipulation. Through the six experiments the evidence accumulates toward the authors' conclusion that manipulating the belief of participants about how much pain another people is really feeling, influences the amount of pain participants report to perceive, and the amount of money they are willing to donate. Furthermore, the results show that belief-manipulation partially mediates the effects on both behavior and neuronal activity.

The major limitation of the manuscript lies in the framing and interpretation of the results, and therefore the evaluation of novelty. Authors claim for an important and unique role of beliefs-of-other-pain in altruistic behavior and empathy for pain. The problem is that these experiments mainly show that behaviors sometimes associated with empathy-for-pain can be cognitively modulated by changing prior beliefs. To support the notion that effects are indeed relating to pain processing generally or empathy for pain specifically, a similar manipulation, done for instance on beliefs about the happiness of others, before recording behavioural estimation of other people's happiness, should have been performed. If such a belief-about-something-else-than-pain would have led to similar results, in terms of behavioural outcome and in terms of TPJ and MFG recapitulating the pattern of behavioral responses, we would know that the results reflect changes of beliefs more generally. Only if the results are specific to a pain-empathy task, would there be evidence to associate the results to pain specifically. But even then, it would remain unclear whether the effects truly relate to empathy for pain, or whether they may reflect other routes of processing pain.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

The authors performed six experiments examining the influence of beliefs regarding pain experience on behavioral and neural indices of empathy for pain and altruistic behavior. They demonstrate that manipulations that to reduce beliefs that individuals making painful expressions are actually in pain (e.g., revealing them to be actors, indicating that their treatment has been successful, etc.) attenuates subjective judgments of pain intensity, real monetary donations to these targets, and P2 amplitudes, and further, that regions involved in perspective-taking and emotion regulation are sensitive to representations of pain beliefs. While I think that the authors have done an admirable job in laying out the evidence for their argument across six well-devised experiments, I do think that the manuscript has some …

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

The authors performed six experiments examining the influence of beliefs regarding pain experience on behavioral and neural indices of empathy for pain and altruistic behavior. They demonstrate that manipulations that to reduce beliefs that individuals making painful expressions are actually in pain (e.g., revealing them to be actors, indicating that their treatment has been successful, etc.) attenuates subjective judgments of pain intensity, real monetary donations to these targets, and P2 amplitudes, and further, that regions involved in perspective-taking and emotion regulation are sensitive to representations of pain beliefs. While I think that the authors have done an admirable job in laying out the evidence for their argument across six well-devised experiments, I do think that the manuscript has some room for improvement. In particular, I hope that the authors can offer stronger grounding in the background literature and clarify some task and stimulus details.

1. In laying out their hypotheses, the authors write, "The current work tested the hypothesis that BOP provides a fundamental cognitive basis of empathy and altruistic behavior by modulating brain activity in response to others' pain. Specifically, we tested predictions that weakening BOP inhibits altruistic behavior by decreasing empathy and its underlying brain activity whereas enhancing BOP may produce opposite effects on empathy and altruistic behavior." While I'm a little dubious regarding the enhancement effects (see below), a supporting assumption here seems to be that at baseline, we expect that painful expressions reflect real pain experience. To that end, it might be helpful to ground some of the introduction in what we know about the perception of painful expressions (e.g., how rapidly/automatically is pain detected, do we preferentially attend to pain vs. other emotions, etc.).

2. For me, the key takeaway from this manuscript was that our assessment of and response to painful expressions is contextually-sensitive - specifically, to information reflecting whether or not targets are actually in pain. As the authors state it, "Our behavioral and neuroimaging results revealed critical functional roles of BOP in modulations of the perception-emotion-behavior reactivity by showing how BOP predicted and affected empathy/empathic brain activity and monetary donations. Our findings provide evidence that BOP constitutes a fundamental cognitive basis for empathy and altruistic behavior in humans." In other words, pain might be an incredibly socially salient signal, but it's still easily overridden from the top down provided relevant contextual information - you won't empathize with something that isn't there. While I think this hypothesis is well-supported by the data, it's also backed by a pretty healthy literature on contextual influences on pain judgments (including in clinical contexts) that I think the authors might want to consider referencing (here are just a few that come to mind: Craig et al., 2010; Twigg et al., 2015; Nicolardi et al., 2020; Martel et al., 2008; Riva et al., 2015; Hampton et al., 2018; Prkachin & Rocha, 2010; Cui et al., 2016).

3. I had a few questions regarding the stimuli the authors used across these experiments. First, just to confirm, these targets were posing (e.g., not experiencing) pain, correct? Second, the authors refer to counterbalancing assignment of these stimuli to condition within the various experiments. Was target gender balanced across groups in this counterbalancing scheme? (e.g., in Experiment 1, if 8 targets were revealed to be actors/actresses in Round 2, were 4 female and 4 male?) Third, were these stimuli selected at random from a larger set, or based on specific criteria (e.g., normed ratings of intensity, believability, specificity of expression, etc.?) If so, it would be helpful to provide these details for each experiment.

4. The nature of the charitable donation (particularly in Experiment 1) could be clarified. I couldn't tell if the same charity was being referenced in Rounds 1 and 2, and if there were multiple charities in Round 2 (one for the patients and one for the actors).

5. I'm also having a hard time understanding the authors' prediction that targets revealed to truly be patients in the 2nd round will be associated with enhanced BOP/altruism/etc. (as they state it: "By contrast, reconfirming patient identities enhanced the coupling between perceived pain expressions of faces and the painful emotional states of face owners and thus increased BOP.") They aren't in any additional pain than they were before, and at the outset of the task, there was no reason to believe that they weren't suffering from this painful condition - therefore I don't see why a second mention of their pain status should *increase* empathy/giving/etc. It seems likely that this is a contrast effect driven by the actor/actress targets. See the Recommendations for the Authors for specific suggestions regarding potential control experiments. (I'll note that the enhancement effect in Experiment 2 seems more sensible - here, the participant learns that treatment was ineffective, which may be painful in and of itself.)

6. I noted that in the Methods for Experiment 3, the authors stated "We recruited only male participants to exclude potential effects of gender difference in empathic neural responses." This approach continues through the rest of the studies. This raises a few questions. Are there gender differences in the first two studies (which recruited both male and female participants)? Moreover, are the authors not concerned about *target* gender effects? (Since, as far as I can tell, all studies use both male and female targets, which would mean that in Experiments 3 and on, half the targets are same-gender as the participants and the other half are other-gender.) Other work suggests that there are indeed effects of target gender on the recognition of painful expressions (Riva et al., 2011).

7. I was a little unclear on the motivation for Experiment 4. The authors state "If BOP rather than other processes was necessary for the modulation of empathic neural responses in Experiment 3, the same manipulation procedure to assign different face identities that do not change BOP should change the P2 amplitudes in response to pain expressions." What "other processes" are they referring to? As far as I could tell, the upshot of this study was just to demonstrate that differences in empathy for pain were not a mere consequence of assignment to social groups (e.g., the groups must have some relevance for pain experience). While the data are clear and as predicted, I'm not sure this was an alternate hypothesis that I would have suggested or that needs disconfirming.

-