A sustained type I IFN-neutrophil-IL-18 axis drives pathology during mucosal viral infection

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

Evaluation Summary:

This manuscript will be of interest to a broad audience of immunologists especially those studying host-pathogen interactions, mucosal immunology, innate immunity and interferons. The study reveals a novel role for neutrophils in the regulation of pathological inflammation during viral infection of the genital mucosa. The main conclusions are well supported by a combination of precise technical approaches including neutrophil-specific gene targeting and antibody-mediated inhibition of selected pathways.

(This preprint has been reviewed by eLife. We include the public reviews from the reviewers here; the authors also receive private feedback with suggested changes to the manuscript. Reviewer #1 and Reviewer #2 agreed to share their names with the authors.)

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

Neutrophil responses against pathogens must be balanced between protection and immunopathology. Factors that determine these outcomes are not well-understood. In a mouse model of genital herpes simplex virus-2 (HSV-2) infection, which results in severe genital inflammation, antibody-mediated neutrophil depletion reduced disease. Comparative single cell RNA-sequencing analysis of vaginal cells against a model of genital HSV-1 infection, which results in mild inflammation, demonstrated sustained expression of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) only after HSV-2 infection primarily within the neutrophil population. Both therapeutic blockade of IFN α/β receptor 1 (IFNAR1) and genetic deletion of IFNAR1 in neutrophils concomitantly decreased HSV-2 genital disease severity and vaginal IL-18 levels. Therapeutic neutralization of IL-18 also diminished genital inflammation, indicating an important role for this cytokine in promoting neutrophil-dependent immunopathology. Our study reveals that sustained type I IFN signaling is a driver of pathogenic neutrophil responses, and identifies IL-18 as a novel component of disease during genital HSV-2 infection.

Article activity feed

-

Author Response:

Evaluation Summary:

This manuscript will be of interest to a broad audience of immunologists especially those studying host-pathogen interactions, mucosal immunology, innate immunity and interferons. The study reveals a novel role for neutrophils in the regulation of pathological inflammation during viral infection of the genital mucosa. The main conclusions are well supported by a combination of precise technical approaches including neutrophil-specific gene targeting and antibody-mediated inhibition of selected pathways.

We would like to thank the reviewers for taking the time to review our manuscript, would also like to thank the editors for handling our manuscript. We are grateful for the positive response to our work and the thoughtful suggestions.

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Overall this is a well-done …

Author Response:

Evaluation Summary:

This manuscript will be of interest to a broad audience of immunologists especially those studying host-pathogen interactions, mucosal immunology, innate immunity and interferons. The study reveals a novel role for neutrophils in the regulation of pathological inflammation during viral infection of the genital mucosa. The main conclusions are well supported by a combination of precise technical approaches including neutrophil-specific gene targeting and antibody-mediated inhibition of selected pathways.

We would like to thank the reviewers for taking the time to review our manuscript, would also like to thank the editors for handling our manuscript. We are grateful for the positive response to our work and the thoughtful suggestions.

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Overall this is a well-done study, but some additional controls and experiments are required, as discussed below. The authors have done a considerable amount of work, resulting in quite a lot of negative data, and so should be commended for persistence to eventually identify the link between neutrophils with IL-18, though type I IFN signaling.

Thank you! We appreciate the feedback and suggestions for strengthening the study.

Major Comments:

-A major conclusion of this manuscript is prolonged type I IFN production following vaginal HSV-2 infection, but the data presented herein did not actually demonstrate this. At 2 days post infection, IFN beta was higher (although not significantly) in HSV-2 infection, but much higher in HSV-1 infection compared to uninfected controls. At 5 days post infection the authors show mRNA data, but not protein data. If the authors are relying on prolonged type I IFN production, then they should demonstrate increased IFN beta during HSV-2 infection at multiple days after infection including 5dpi and 7dpi.

We apologize for not including the IFN protein data and have now have provided this information in new Figure 3 and Figure 3 - Supplement 3. This new addition shows measurement of secreted IFNb in vaginal lavages at 4, 5 and 7 d.p.i., as well as total IFNb levels in vaginal tissue at 7 d.p.i..

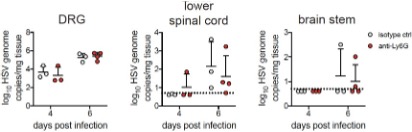

-Does the CNS viral load or kinetics of viral entry into the CNS differ in mice depleted of neutrophils, IFNAR cKO mice, or mice treated with anti- IL-18? Do neutrophils and/or IL-18 participate at all in neuronal protection from infection?

To maintain the focus of our study on the host factors that contribute specifically to genital disease, we have not included discussion on viral dissemination into the PNS or CNS, especially as viral invasion of

the CNS seems to be an infrequent occurrence during genital herpes in humans. However, we have performed some preliminary exploration of this interesting question, and find that viral invasion of the nervous system is unaltered in the absence of neutrophils. This is in accordance with the lack of antiviral neutrophil activity we have described in the vagina after HSV-2 infection. These preliminary data are provided below as a Reviewer Figure 1. We have not yet begun to investigate whether IL-18 modulates neuroprotection, but agree this is an important question to address in future studies.

RFigure 1. Viral burden in the nervous system is similar in the presence or absence of neutrophils. Graphs show viral genomes measured by qPCR from the DRG, lower half of of the spinal cord and the brainstem at the indicated days post- infection.

-In Figure 3 the authors show that neutrophil "infection" clusters 2 and 5 express high levels of ISGs. Only 4 of these ISGs are shown in the accompanying figures. Please list which ISGs were increased in neutrophils after both HSV-2 and HSV-1 infection, perhaps in a table. Were there any ISGs specifically higher after HSV-2 infection alone, any after HSV-1 infection alone?

These tables listing differentially-expressed neutrophils ISGs during HSV-1 and HSV-2 have now been provided in new Figure 3 - Supplement 1, with complete lists of DEGs provided as Source Files for the same figure.

-The authors claim that HSV-1 infection recruits non-pathogenic neutrophils compared to the pathogenic neutrophils recruited during HSV-2 infection. Can the authors please discuss if these differences in inflammation or transcriptional differences between the neutrophils in these two different infections could be due to differences in host response to these two viruses rather than differences in inflammation? Please elaborate on why HSV-1 used as opposed to a less inflammatory strain of HSV-2. Furthermore, does HSV-1 infection induce vaginal IL-18 production in a neutrophil-dependent fashion as well?

These are excellent questions, and we have emphasized that differences in host responses against HSV-1 and HSV-2 likely lead to distinct inflammatory milieus that differentially affect neutrophil responses in lines 374-375 and 409-419. We completely agree that differences in neutrophil responses are likely due to distinct host responses against HSV-1 and HSV-2 and apologize for not making that clear. We have previously described some of the other differences in the immunological response against these two viruses (Lee et al, JCI Insight 2020). We would suggest that differences in the host response against these two viruses would naturally result in differences in the local inflammatory milieu, which then modulates neutrophil responses. Whether the transcriptomes of neutrophils beyond the immediate site of infection (outside the vagina) are different between HSV-1 and HSV-2 is currently an open question.

As for why we used HSV-1 instead of a less inflammatory strain of HSV-2, we had originally been interested in trying to model the distinct disease outcomes that have previously been described during HSV-1 vs HSV-2 genital herpes in humans and thought this would be a relevant comparison. We have not yet examined infection with less inflammatory HSV-2 strains, but agree that this is a great idea. We have also not yet examined neutrophil-dependent IL-18 production in the context of HSV-1.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

This manuscript will be of interest to a broad audience of immunologists especially those studying host-pathogen interactions, mucosal immunology, innate immunity and interferons. The study reveals a novel role for neutrophils in the regulation of pathological inflammation during viral infection of the genital mucosa. The main conclusions are well supported by a combination of precise technical approaches including neutrophil-specific gene targeting and antibody-mediated inhibition of selected pathways.

In this study by Lebratti, et al the authors examined the impact of neutrophil depletion on disease progression, inflammation and viral control during a genital infection with HSV-2. They find that removal of neutrophils prior to HSV-2 infection resulted in ameliorated disease as assessed by inflammatory score measurements. Importantly, they show that neutrophil depletion had no significant impact on viral burden nor did it affect the recruitment of other immune cells thus suggesting that the observed improvement on inflammation was a direct effect of neutrophils. The role of neutrophils in promoting inflammation appears to be specific to HSV-2 since the authors show that HSV-1 infection resulted in comparable numbers of neutrophils being recruited to the vagina yet HSV-1 infection was less inflammatory. This observation thus suggests that there might be functional differences in neutrophils in the context of HSV-2 versus HSV-1 infection that could underlie the distinct inflammatory outcomes observed in each infection. In ordered to uncover potential mechanisms by which neutrophils affect inflammation the authors examined the contributions of classical neutrophil effector functions such as NETosis (by studying neutrophil-specific PAD4 deficient mice), reactive oxygen species (using mice global defect in NADH oxidase function) and cytokine/phagocytosis (by studying neutrophil-specific STIM-1/STIM-2 deficient mice). The data shown convincingly ruled out a contribution by the neutrophil factors examined. The authors thus performed an unbiased single cell transcriptomic analysis of vaginal tissue during HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection in search for potentially novel factors that differentially regulate inflammation in these two infections. tSNE analysis of the data revealed the presence of three distinct clusters of neutrophils in vaginal tissue in mock infected mice, the same three clusters remained after HSV-1 infection but in response to HSV-2 only two of the clusters remained and showed a sustained interferon signature primarily driven by type I interferons (IFNs). In order to directly interrogate the impact of type I IFN on the regulation of inflammation the authors blocked type I IFN signaling (using anti IFNAR antibodies) at early or late times after infection and showed that late (day 4) IFN signaling was promoting inflammation while early (before infection) IFN was required for antiviral defense as expected. Importantly, the authors examined the impact of neutrophil-intrinsic IFN signaling on HSV-2 infection using neutrophil-specific IFNAR1 knockout mice (IFNAR1 CKO). The genetic ablation of IFNAR1 on neutrophils resulted in reduced inflammation in response to HSV-2 infection but no impact on viral titers; findings that are consistent with observations shown for neutrophil-depleted mice. The use of IFNAR1 CKO mice strongly support the importance of type I IFN signaling on neutrophils as direct regulators of neutrophil inflammatory activity in this model. Since type I IFNs induce the expression of multiple genes that could affect neutrophils and inflammation in various ways the authors set out to identify specific downstream effectors responsible for the observed inflammatory phenotype. This search lead them to IL-18 as possible mediator. They showed that IL-18 levels in the vagina during HSV-2 infection were reduced in neutrophil-depleted mice, in mice with "late" IFNAR blockade and in IFNAR1 CKO mice. Furthermore, they showed that antibody-mediated neutralization of IL-18 ameliorated the inflammatory response of HSV-2 infected mice albeit to a lesser extent that what was seen in IFNAR1 CKO. Altogether, the study presents intriguing data to support a new role for neutrophils as regulators of inflammation during viral infection via an IFN-IL-18 axis.

In aggregate, the data shown support the author's main conclusions, but some of the technical approaches need clarification and in some cases further validation that they are working as intended.

Thank you! We appreciate the enthusiasm for our work as well as the suggestions for improving our study.

- The use of anti-Ly6G antibodies (clone 1A8) to target neutrophil depletion in mice has been shown to be more specific than anti-Gr1 antibodies (which targets both monocytes and neutrophils) thus anti-Ly6G antibodies are a good technical choice for the study. Neutrophils are notoriously difficult to deplete efficiently in vivo due at least in part to their rapid regeneration in the bone marrow. In order to sustain depletion, previous reports indicate the need for daily injection of antibodies. In the current study the authors report the use of only one, intra-peritoneal injection (500 mg) of 1A8 antibodies and that this single treatment resulted in diminished neutrophil numbers in the vagina at day 5 after viral infection (Fig 1A). Data shown in figure 2B suggests that there are neutrophils present in the vagina of uninfected mice, that there is a significant increase in their numbers at day 2 and that their numbers remain fairly steady from days 2 to 5 after infection. In order to better understand the impact antibody-mediated depletion in this model the authors should have examined the kinetics of depletion from day 0 through 5 in the vaginal tissue after 1A8 injection as compared to the effect of antibodies in the periphery. These additional data sets would allow for a deeper understanding of neutrophil responses in the vagina as compared to what has been published in other models of infection at other mucosal sites.

We agree and apologize for not providing this information in the original submission. Neutrophil depletion kinetics from the vagina have been shown in new Figure 1A, while depletion from the blood is shown in new Figure 1 - Supplement 1.

- The authors used antibody-mediated blockade as a means to interrogate the impact of type I IFNs and IL-18 in their model. The kinetics of IFNAR blockade were nicely explained and supported by data shown in supplementary figure 4. IFNAR blockade was done by intra-peritoneal delivery of antibodies at one day before infection or at day 4 after infection. When testing the role of IL-18 the authors delivered the blocking antibody intra-vaginally at 3 days post infection. The authors do not provide a rationale for changing delivery method and timing of antibody administration to target IL-18 relative to IFNAR signaling. Since the model presented argues for an upstream role for IFNAR as inducer of IL-18 it is unclear why the time point used to target IL-18 is before the time used for IFNAR.

We thank Reviewer #2 for raising this point and apologize for not providing an explanation for the differences in antibody treatment regimens for modulating IFNAR and IL-18. As the anti-IL-18 mAb is a cytokine neutralizing antibody, we hypothesized that administering the antibody vaginally would help to concentrate the antibody at the relevant site of cytokine production and increase the potency of neutralization. This is in contrast to systemic administration of the anti-IFNAR1 mAb that acts to block signaling in the 'receiving' cell. We expect the anti-IFNAR1 mAb (given in much higher doses) to bind both circulating cells that are recruited to the site of infection as well as cells that are already at the site of infection. Similarly, we started the anti-IL-18 antibody treatment one day earlier to allow a presumably sufficient amount antibody to accumulate in the vagina. Our rationale has been included in the revised manuscript (lines 351-353). We are pleased to report, however, that we have conducted preliminary studies in which mice were treated beginning at 4 d.p.i. rather than 3 d.p.i., and observe similar trends. This data is provided below as Reviewer Figure 3.

RFigure 3. Mice treated with anti-IL-18 mAb starting at 4 d.p.i. exhibit reduced disease severity. Mice were infected with HSV-2 and treated ivag with 100ug of anti-IL-18 on 4, 5 and 6 d.p.i.. Mice were monitored for disease until 7 d.p.i.. Data was analyzed by repeated measured two-way ANOVA with Geisser-Greenhouse correction and Bonferroni's multiple comparisons test.

- An open question that remains is the potential mechanism by which IL-18 is acting as effector cytokine of epithelial damage. As acknowledged by the authors the rescue seen in IFNAR1 CKO mice (Fig 5C) is more dramatic that targeting IL-18 (Fig 6D). It is thus very likely that IFNAR signaling on neutrophils is affecting other pathways. It would have been greatly insightful to perform a single cell RNA seq experiment with IFNAR CKO mice as done for WT mice in Fig 3. Such an analysis might would have provided a more thorough understanding of neutrophil-mediated inflammatory pathways that operate outside of classical neutrophil functions.

We agree that the proposed scRNA-seq experiment comparing vaginal cells from IFNAR CKO and WT mice would be very interesting and insightful. Although a bit beyond the scope of the current manuscript, we are currently planning on performing these types of studies to better understand IFN-mediated regulation of inflammatory neutrophil functions.

- The inflammatory score scale used is nicely described in the methods and it took into consideration external signs of vaginal inflammation by visual observation. It would have been helpful to mention whether the inflammation scoring was done by individuals blinded to the experimental groups.

This is an important point and we apologize for not making this clear. We have now provided this information in the methods section of the revised manuscript (lines 778).

- The presence of distinct clusters of neutrophils in the scRNA-seq data analysis is a fascinating observation that might suggest more diversity in neutrophils than what is currently appreciated. In this study, the authors do not provide a list of the genes expressed in each cluster within the data shown in the paper. Although the entire data set is deposited and publicly available, having the gene lists within the paper would have been helpful to provide a deeper understanding of the current study.

The heterogeneity of the vaginal neutrophil population after HSV infection is indeed an unexpected finding. To provide a deeper understanding of these transcriptionally distinct clusters, we have now included complete lists of DEGs between the different clusters as Source Files for Figure 3.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

This paper examines the role of neutrophils, inflammatory immune cells, in disease caused by genital herpes virus infection. The experiments describe a role for type I interferon stimulation of neutrophils later in the infection that drives inflammation. Blockade of interferon, and to a lesser degree, IL-18 ameliorated disease. This study should be of interest to immunologists and virologists.

This study sought to examine the role of neutrophils in pathology during mucosal HSV-2 infection in a mouse model. The data presented in this manuscript suggest that late or sustained IFN-I signals act on neutrophils to drive inflammation and pathology in genital herpes infection. The authors show that while depletion of neutrophils from mice does not impact viral clearance or recruitment of other immune cells to the infected tissue, it did reduce inflammation in the mucosa and genital skin. Single cell sequencing of immune cells from the infected mucosa revealed increased expression of interferon stimulated genes (ISGs) in neutrophils and myeloid cells in HSV-2 infected mice. Treatment of anti-IFNAR antibodies or neutrophil-specific IFNAR1 conditional knockout mice decreased disease and IL-18 levels. Blocking IL-18 also reduced disease, although these data show that other signals are likely to also be involved. It is interesting that viral titers and anti-viral immune responses were unaffected by IFNAR or IL-18 blockade when this treatment was started 3-4 days after infection, because data shown here (for IFN-I) and by others in published studies (for IFN-I or IL-18) have shown that loss of IFN-I or IL-18 prior to infection is detrimental.

These data are interesting and show pathways (namely IFN-I and IL-18) that could be blocked to limit disease. While this suggests that IL-18 blockade might be an effective treatment for genital inflammation caused by HSV-2 infection, the utility of IL-18 blockade is still unclear, because the magnitude of the effect in this mouse model was less than IFNAR blockade. Additionally, further experiments, such as conditional loss of IL-18 in neutrophils, would be required to better define the role and source(s) of IL-18 that drive disease in this model.

We thank the reviewer for the positive response and agree that additional studies would likely be necessary to fully understand the role of IL-18 during HSV-2 infection.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

This paper examines the role of neutrophils, inflammatory immune cells, in disease caused by genital herpes virus infection. The experiments describe a role for type I interferon stimulation of neutrophils later in the infection that drives inflammation. Blockade of interferon, and to a lesser degree, IL-18 ameliorated disease. This study should be of interest to immunologists and virologists.

This study sought to examine the role of neutrophils in pathology during mucosal HSV-2 infection in a mouse model. The data presented in this manuscript suggest that late or sustained IFN-I signals act on neutrophils to drive inflammation and pathology in genital herpes infection. The authors show that while depletion of neutrophils from mice does not impact viral clearance or recruitment of other immune cells to the …

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

This paper examines the role of neutrophils, inflammatory immune cells, in disease caused by genital herpes virus infection. The experiments describe a role for type I interferon stimulation of neutrophils later in the infection that drives inflammation. Blockade of interferon, and to a lesser degree, IL-18 ameliorated disease. This study should be of interest to immunologists and virologists.

This study sought to examine the role of neutrophils in pathology during mucosal HSV-2 infection in a mouse model. The data presented in this manuscript suggest that late or sustained IFN-I signals act on neutrophils to drive inflammation and pathology in genital herpes infection. The authors show that while depletion of neutrophils from mice does not impact viral clearance or recruitment of other immune cells to the infected tissue, it did reduce inflammation in the mucosa and genital skin. Single cell sequencing of immune cells from the infected mucosa revealed increased expression of interferon stimulated genes (ISGs) in neutrophils and myeloid cells in HSV-2 infected mice. Treatment of anti-IFNAR antibodies or neutrophil-specific IFNAR1 conditional knockout mice decreased disease and IL-18 levels. Blocking IL-18 also reduced disease, although these data show that other signals are likely to also be involved. It is interesting that viral titers and anti-viral immune responses were unaffected by IFNAR or IL-18 blockade when this treatment was started 3-4 days after infection, because data shown here (for IFN-I) and by others in published studies (for IFN-I or IL-18) have shown that loss of IFN-I or IL-18 prior to infection is detrimental.

These data are interesting and show pathways (namely IFN-I and IL-18) that could be blocked to limit disease. While this suggests that IL-18 blockade might be an effective treatment for genital inflammation caused by HSV-2 infection, the utility of IL-18 blockade is still unclear, because the magnitude of the effect in this mouse model was less than IFNAR blockade. Additionally, further experiments, such as conditional loss of IL-18 in neutrophils, would be required to better define the role and source(s) of IL-18 that drive disease in this model.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

This manuscript will be of interest to a broad audience of immunologists especially those studying host-pathogen interactions, mucosal immunology, innate immunity and interferons. The study reveals a novel role for neutrophils in the regulation of pathological inflammation during viral infection of the genital mucosa. The main conclusions are well supported by a combination of precise technical approaches including neutrophil-specific gene targeting and antibody-mediated inhibition of selected pathways.

In this study by Lebratti, et al the authors examined the impact of neutrophil depletion on disease progression, inflammation and viral control during a genital infection with HSV-2. They find that removal of neutrophils prior to HSV-2 infection resulted in ameliorated disease as assessed by inflammatory …

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

This manuscript will be of interest to a broad audience of immunologists especially those studying host-pathogen interactions, mucosal immunology, innate immunity and interferons. The study reveals a novel role for neutrophils in the regulation of pathological inflammation during viral infection of the genital mucosa. The main conclusions are well supported by a combination of precise technical approaches including neutrophil-specific gene targeting and antibody-mediated inhibition of selected pathways.

In this study by Lebratti, et al the authors examined the impact of neutrophil depletion on disease progression, inflammation and viral control during a genital infection with HSV-2. They find that removal of neutrophils prior to HSV-2 infection resulted in ameliorated disease as assessed by inflammatory score measurements. Importantly, they show that neutrophil depletion had no significant impact on viral burden nor did it affect the recruitment of other immune cells thus suggesting that the observed improvement on inflammation was a direct effect of neutrophils. The role of neutrophils in promoting inflammation appears to be specific to HSV-2 since the authors show that HSV-1 infection resulted in comparable numbers of neutrophils being recruited to the vagina yet HSV-1 infection was less inflammatory. This observation thus suggests that there might be functional differences in neutrophils in the context of HSV-2 versus HSV-1 infection that could underlie the distinct inflammatory outcomes observed in each infection. In ordered to uncover potential mechanisms by which neutrophils affect inflammation the authors examined the contributions of classical neutrophil effector functions such as NETosis (by studying neutrophil-specific PAD4 deficient mice), reactive oxygen species (using mice global defect in NADH oxidase function) and cytokine/phagocytosis (by studying neutrophil-specific STIM-1/STIM-2 deficient mice). The data shown convincingly ruled out a contribution by the neutrophil factors examined. The authors thus performed an unbiased single cell transcriptomic analysis of vaginal tissue during HSV-1 and HSV-2 infection in search for potentially novel factors that differentially regulate inflammation in these two infections. tSNE analysis of the data revealed the presence of three distinct clusters of neutrophils in vaginal tissue in mock infected mice, the same three clusters remained after HSV-1 infection but in response to HSV-2 only two of the clusters remained and showed a sustained interferon signature primarily driven by type I interferons (IFNs). In order to directly interrogate the impact of type I IFN on the regulation of inflammation the authors blocked type I IFN signaling (using anti IFNAR antibodies) at early or late times after infection and showed that late (day 4) IFN signaling was promoting inflammation while early (before infection) IFN was required for antiviral defense as expected. Importantly, the authors examined the impact of neutrophil-intrinsic IFN signaling on HSV-2 infection using neutrophil-specific IFNAR1 knockout mice (IFNAR1 CKO). The genetic ablation of IFNAR1 on neutrophils resulted in reduced inflammation in response to HSV-2 infection but no impact on viral titers; findings that are consistent with observations shown for neutrophil-depleted mice. The use of IFNAR1 CKO mice strongly support the importance of type I IFN signaling on neutrophils as direct regulators of neutrophil inflammatory activity in this model. Since type I IFNs induce the expression of multiple genes that could affect neutrophils and inflammation in various ways the authors set out to identify specific downstream effectors responsible for the observed inflammatory phenotype. This search lead them to IL-18 as possible mediator. They showed that IL-18 levels in the vagina during HSV-2 infection were reduced in neutrophil-depleted mice, in mice with "late" IFNAR blockade and in IFNAR1 CKO mice. Furthermore, they showed that antibody-mediated neutralization of IL-18 ameliorated the inflammatory response of HSV-2 infected mice albeit to a lesser extent that what was seen in IFNAR1 CKO. Altogether, the study presents intriguing data to support a new role for neutrophils as regulators of inflammation during viral infection via an IFN-IL-18 axis.

In aggregate, the data shown support the author's main conclusions, but some of the technical approaches need clarification and in some cases further validation that they are working as intended.

The use of anti-Ly6G antibodies (clone 1A8) to target neutrophil depletion in mice has been shown to be more specific than anti-Gr1 antibodies (which targets both monocytes and neutrophils) thus anti-Ly6G antibodies are a good technical choice for the study. Neutrophils are notoriously difficult to deplete efficiently in vivo due at least in part to their rapid regeneration in the bone marrow. In order to sustain depletion, previous reports indicate the need for daily injection of antibodies. In the current study the authors report the use of only one, intra-peritoneal injection (500 mg) of 1A8 antibodies and that this single treatment resulted in diminished neutrophil numbers in the vagina at day 5 after viral infection (Fig 1A). Data shown in figure 2B suggests that there are neutrophils present in the vagina of uninfected mice, that there is a significant increase in their numbers at day 2 and that their numbers remain fairly steady from days 2 to 5 after infection. In order to better understand the impact antibody-mediated depletion in this model the authors should have examined the kinetics of depletion from day 0 through 5 in the vaginal tissue after 1A8 injection as compared to the effect of antibodies in the periphery. These additional data sets would allow for a deeper understanding of neutrophil responses in the vagina as compared to what has been published in other models of infection at other mucosal sites.

The authors used antibody-mediated blockade as a means to interrogate the impact of type I IFNs and IL-18 in their model. The kinetics of IFNAR blockade were nicely explained and supported by data shown in supplementary figure 4. IFNAR blockade was done by intra-peritoneal delivery of antibodies at one day before infection or at day 4 after infection. When testing the role of IL-18 the authors delivered the blocking antibody intra-vaginally at 3 days post infection. The authors do not provide a rationale for changing delivery method and timing of antibody administration to target IL-18 relative to IFNAR signaling. Since the model presented argues for an upstream role for IFNAR as inducer of IL-18 it is unclear why the time point used to target IL-18 is before the time used for IFNAR.

An open question that remains is the potential mechanism by which IL-18 is acting as effector cytokine of epithelial damage. As acknowledged by the authors the rescue seen in IFNAR1 CKO mice (Fig 5C) is more dramatic that targeting IL-18 (Fig 6D). It is thus very likely that IFNAR signaling on neutrophils is affecting other pathways. It would have been greatly insightful to perform a single cell RNA seq experiment with IFNAR CKO mice as done for WT mice in Fig 3. Such an analysis might would have provided a more thorough understanding of neutrophil-mediated inflammatory pathways that operate outside of classical neutrophil functions.

The inflammatory score scale used is nicely described in the methods and it took into consideration external signs of vaginal inflammation by visual observation. It would have been helpful to mention whether the inflammation scoring was done by individuals blinded to the experimental groups.

The presence of distinct clusters of neutrophils in the scRNA-seq data analysis is a fascinating observation that might suggest more diversity in neutrophils than what is currently appreciated. In this study, the authors do not provide a list of the genes expressed in each cluster within the data shown in the paper. Although the entire data set is deposited and publicly available, having the gene lists within the paper would have been helpful to provide a deeper understanding of the current study.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Overall this is a well-done study, but some additional controls and experiments are required, as discussed below. The authors have done a considerable amount of work, resulting in quite a lot of negative data, and so should be commended for persistence to eventually identify the link between neutrophils with IL-18, though type I IFN signaling.

Major Comments:

A major conclusion of this manuscript is prolonged type I IFN production following vaginal HSV-2 infection, but the data presented herein did not actually demonstrate this. At 2 days post infection, IFN beta was higher (although not significantly) in HSV-2 infection, but much higher in HSV-1 infection compared to uninfected controls. At 5 days post infection the authors show mRNA data, but not protein data. If the authors are relying on prolonged type I …

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

Overall this is a well-done study, but some additional controls and experiments are required, as discussed below. The authors have done a considerable amount of work, resulting in quite a lot of negative data, and so should be commended for persistence to eventually identify the link between neutrophils with IL-18, though type I IFN signaling.

Major Comments:

A major conclusion of this manuscript is prolonged type I IFN production following vaginal HSV-2 infection, but the data presented herein did not actually demonstrate this. At 2 days post infection, IFN beta was higher (although not significantly) in HSV-2 infection, but much higher in HSV-1 infection compared to uninfected controls. At 5 days post infection the authors show mRNA data, but not protein data. If the authors are relying on prolonged type I IFN production, then they should demonstrate increased IFN beta during HSV-2 infection at multiple days after infection including 5dpi and 7dpi.

Does the CNS viral load or kinetics of viral entry into the CNS differ in mice depleted of neutrophils, IFNAR cKO mice, or mice treated with anti- IL-18? Do neutrophils and/or IL-18 participate at all in neuronal protection from infection?

In Figure 3 the authors show that neutrophil "infection" clusters 2 and 5 express high levels of ISGs. Only 4 of these ISGs are shown in the accompanying figures. Please list which ISGs were increased in neutrophils after both HSV-2 and HSV-1 infection, perhaps in a table. Were there any ISGs specifically higher after HSV-2 infection alone, any after HSV-1 infection alone?

The authors claim that HSV-1 infection recruits non-pathogenic neutrophils compared to the pathogenic neutrophils recruited during HSV-2 infection. Can the authors please discuss if these differences in inflammation or transcriptional differences between the neutrophils in these two different infections could be due to differences in host response to these two viruses rather than differences in inflammation? Please elaborate on why HSV-1 used as opposed to a less inflammatory strain of HSV-2. Furthermore, does HSV-1 infection induce vaginal IL-18 production in a neutrophil-dependent fashion as well?

-

Evaluation Summary:

This manuscript will be of interest to a broad audience of immunologists especially those studying host-pathogen interactions, mucosal immunology, innate immunity and interferons. The study reveals a novel role for neutrophils in the regulation of pathological inflammation during viral infection of the genital mucosa. The main conclusions are well supported by a combination of precise technical approaches including neutrophil-specific gene targeting and antibody-mediated inhibition of selected pathways.

(This preprint has been reviewed by eLife. We include the public reviews from the reviewers here; the authors also receive private feedback with suggested changes to the manuscript. Reviewer #1 and Reviewer #2 agreed to share their names with the authors.)

-