HIV status alters disease severity and immune cell responses in Beta variant SARS-CoV-2 infection wave

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

Evaluation Summary:

This manuscript is of primary interest to readers in the field of infectious diseases especially the ones involved in COVID-19 research. The identification of immunological signatures caused by SARS-CoV-2 in HIV-infected individuals is important not only to better predict disease outcomes but also to predict vaccine efficacy and to potentially identify sources of viral variants. In here, the authors leverage a combination of clinical parameters, limited virologic information and extensive flow cytometry data to reach descriptive conclusions.

(This preprint has been reviewed by eLife. We include the public reviews from the reviewers here; the authors also receive private feedback with suggested changes to the manuscript. The reviewers remained anonymous to the authors.)

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

- Evaluated articles (ScreenIT)

Abstract

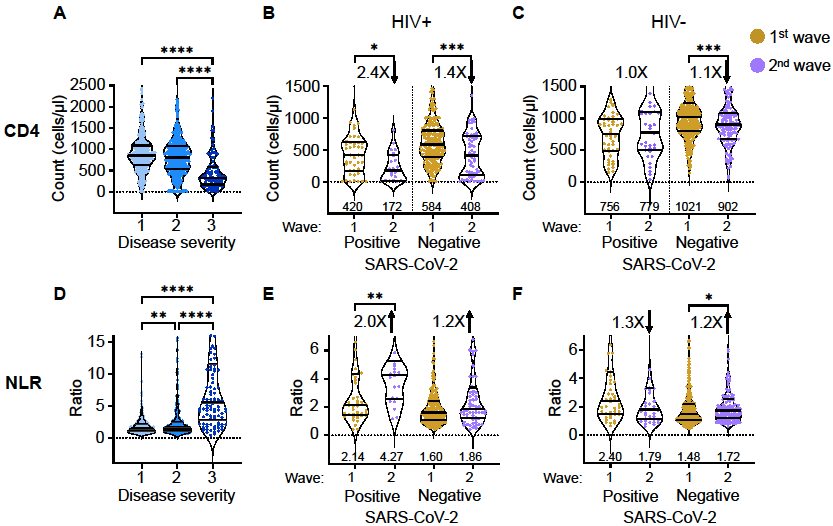

There are conflicting reports on the effects of HIV on COVID-19. Here, we analyzed disease severity and immune cell changes during and after SARS-CoV-2 infection in 236 participants from South Africa, of which 39% were people living with HIV (PLWH), during the first and second (Beta dominated) infection waves. The second wave had more PLWH requiring supplemental oxygen relative to HIV-negative participants. Higher disease severity was associated with low CD4 T cell counts and higher neutrophil to lymphocyte ratios (NLR). Yet, CD4 counts recovered and NLR stabilized after SARS-CoV-2 clearance in wave 2 infected PLWH, arguing for an interaction between SARS-CoV-2 and HIV infection leading to low CD4 and high NLR. The first infection wave, where severity in HIV negative and PLWH was similar, still showed some HIV modulation of SARS-CoV-2 immune responses. Therefore, HIV infection can synergize with the SARS-CoV-2 variant to change COVID-19 outcomes.

Article activity feed

-

-

Author Response:

Evaluation Summary:

This manuscript is of primary interest to readers in the field of infectious diseases especially the ones involved in COVID-19 research. The identification of immunological signatures caused by SARS-CoV-2 in HIV-infected individuals is important not only to better predict disease outcomes but also to predict vaccine efficacy and to potentially identify sources of viral variants. In here, the authors leverage a combination of clinical parameters, limited virologic information and extensive flow cytometry data to reach descriptive conclusions.

We have extensively reworked the paper.

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The methods appear sound. The introduction of vaccines for COVID-19 and the emergence of variants in South Africa and how they may impact PLWH is well discussed making the findings …

Author Response:

Evaluation Summary:

This manuscript is of primary interest to readers in the field of infectious diseases especially the ones involved in COVID-19 research. The identification of immunological signatures caused by SARS-CoV-2 in HIV-infected individuals is important not only to better predict disease outcomes but also to predict vaccine efficacy and to potentially identify sources of viral variants. In here, the authors leverage a combination of clinical parameters, limited virologic information and extensive flow cytometry data to reach descriptive conclusions.

We have extensively reworked the paper.

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The methods appear sound. The introduction of vaccines for COVID-19 and the emergence of variants in South Africa and how they may impact PLWH is well discussed making the findings presented a good reference backdrop for future assessment. Good literature review is also presented. Specific suggestions for improving the manuscript have been identified and conveyed to the authors.

We thank the Reviewer for the support.

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Karima, Gazy, Cele, Zungu, Krause et al. described the impact of HIV status on the immune cell dynamics in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection. To do so, during the peak of the KwaZulu-Natal pandemic, in July 2020, they enrolled a robust observational longitudinal cohort of 124 participants all positive for SARS-CoV-2. Of the participants, a group of 55 people (44%) were HIV-infected individuals. No difference is COVID-19 high risk comorbidities of clinical manifestations were observed in people living with HIV (PLWH) versus HIV-uninfected individuals exception made for joint ache which was more present in HIV-uninfected individuals. In this study, the authors leverage and combine extensive clinical information, virologic data and immune cells quantification by flow cytometry to show changes in T cells such as post-SARS-CoV-2 infection expansion of CD8 T cells and reduced expression CXCR3 on T cells in specific post-SARS-CoV-2 infection time points. The authors also conclude that the HIV status attenuates the expansion of antibody secreting cells. The correlative analyses in this study show that low CXCR3 expression on CD8 and CD4 T cells correlates with Covid-19 disease severity, especially in PLWH. The authors did not observe differences in SARS-CoV-2 shedding time frame in the two groups excluding that HIV serostatus plays a role in the emergency of SARS-CoV-2 variants. However, the authors clarify that their PLWH group consisted of mostly ART suppressed participants whose CD4 counts were reasonably high. The study presents the following strengths and limitations

We thank the Reviewer for the comments. The cohort now includes participants with low CD4.

Strengths:

A. A robust longitudinal observational cohort of 124 study participants, 55 of whom were people living with HIV. This cohort was enrolled in KwaZulu-Natal,South Africa during the peak of the pandemic. The participants were followed for up to 5 follow up visits and around 50% of the participants have completed the study.

We thank the Reviewer for the support. The cohort has now been expanded to 236 participants.

B. A broad characterization of blood circulating cell subsets by flow cytometry able to identify and characterize T cells, B cells and innate cells.

We thank the Reviewer for the support.

Weaknesses:

The study design does not include

A. a robust group of HIV-infected individuals with low CD4 counts, as also stated by the authors

This has changed in the resubmission because we included participants from the second, beta variant dominated infection wave. For this infection wave we obtained what we think is an important result, presented in a new Figure 2:

This figure shows that in infection wave 2 (beta variant), CD4 counts for PLWH dropped to below the CD4=200 level, yet recovered after SARS-CoV-2 clearance. Therefore, the participants we added had low CD4 counts, but this was SARS-CoV-2 dependent.

B. a group of HIV-uninfected individuals and PLWH with severe COVID-19. As stated in the manuscript the majority of our participants did not progress beyond outcome 4 of the WHO ordinal scale. This is also reflected in the age average of the participants. Limiting the number of participants characterized by severe COVID-19 limits the study to an observational correlative study

Death has now been added to Table 1 under the “Disease severity” subheading. The number of participants who have died, at 13, is relatively small. We did not limit the study to non-critical cases. Our main measure of severity is supplemental oxygen.

This is stated in the Results, line 106-108:

“Our cohort design did not specifically enroll critical SARS-CoV-2 cases. The requirement for supplemental oxygen, as opposed to death, was therefore our primary measure for disease severity.”

This is justified in the Discussion, lines 219-225:

“Our cohort may not be a typical 'hospitalized cohort' as the majority of participants did not require supplemental oxygen. We therefore cannot discern effects of HIV on critical SARS-CoV-2 cases since these numbers are too small in the cohort. However, focusing on lower disease severity enabled us to capture a broader range of outcomes which predominantly ranged from asymptomatic to supplemental oxygen, the latter being our main measure of more severe disease. Understanding this part of the disease spectrum is likely important, since it may indicate underlying changes in the immune response which could potentially affect long-term quality of life and response to vaccines.”

C. a control group enrolled at the same time of the study of HIV-uninfected and infected individuals.

This was not possible given constraints imposed on bringing non-SARS-CoV-2 infected participants into a hospital during a pandemic for research purposes. However, given that the study was longitudinal, we did track participants after convalescence. This gave us an approximation of participant baseline in the absence of SARS-CoV-2, for the same participants. Results are presented in Figure 2 above.

D. results that elucidate the mechanisms and functions of immune cells subsets in the contest of COVID-19.

We do not have functional assays.

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Karim et al have assembled a large cohort of PLWH with acute COVID-19 and well-matched controls. The main finding is that, despite similar clinical and viral (e.g., shedding) outcomes, the immune response to COVID-19 in PLWH differs from the immune response to COVID-19 in HIV uninfected individuals. More specifically, they find that viral loads are comparable between the groups at the time of diagnosis, and that the time to viral clearance (by PCR) is also similar between the two groups. They find that PLWH have higher proportions and also higher absolute number of CD8 cells in the 2-3 weeks after initial infection.

The authors do a wonderful job of clinically characterizing the research participants. I was most impressed by the attention to detail with respect to timing of viral diagnosis as it related to symptom onset and specimen collection. I was also impressed by the number of longitudinal samples included in this study.

We thank the Reviewer for the support.

-

Evaluation Summary:

This manuscript is of primary interest to readers in the field of infectious diseases especially the ones involved in COVID-19 research. The identification of immunological signatures caused by SARS-CoV-2 in HIV-infected individuals is important not only to better predict disease outcomes but also to predict vaccine efficacy and to potentially identify sources of viral variants. In here, the authors leverage a combination of clinical parameters, limited virologic information and extensive flow cytometry data to reach descriptive conclusions.

(This preprint has been reviewed by eLife. We include the public reviews from the reviewers here; the authors also receive private feedback with suggested changes to the manuscript. The reviewers remained anonymous to the authors.)

-

Reviewer #1 (Public Review):

The methods appear sound. The introduction of vaccines for COVID-19 and the emergence of variants in South Africa and how they may impact PLWH is well discussed making the findings presented a good reference backdrop for future assessment. Good literature review is also presented. Specific suggestions for improving the manuscript have been identified and conveyed to the authors.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Karima, Gazy, Cele, Zungu, Krause et al. described the impact of HIV status on the immune cell dynamics in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection. To do so, during the peak of the KwaZulu-Natal pandemic, in July 2020, they enrolled a robust observational longitudinal cohort of 124 participants all positive for SARS-CoV-2. Of the participants, a group of 55 people (44%) were HIV-infected individuals. No difference is COVID-19 high risk comorbidities of clinical manifestations were observed in people living with HIV (PLWH) versus HIV-uninfected individuals exception made for joint ache which was more present in HIV-uninfected individuals. In this study, the authors leverage and combine extensive clinical information, virologic data and immune cells quantification by flow cytometry to show changes in T cells such as …

Reviewer #2 (Public Review):

Karima, Gazy, Cele, Zungu, Krause et al. described the impact of HIV status on the immune cell dynamics in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection. To do so, during the peak of the KwaZulu-Natal pandemic, in July 2020, they enrolled a robust observational longitudinal cohort of 124 participants all positive for SARS-CoV-2. Of the participants, a group of 55 people (44%) were HIV-infected individuals. No difference is COVID-19 high risk comorbidities of clinical manifestations were observed in people living with HIV (PLWH) versus HIV-uninfected individuals exception made for joint ache which was more present in HIV-uninfected individuals. In this study, the authors leverage and combine extensive clinical information, virologic data and immune cells quantification by flow cytometry to show changes in T cells such as post-SARS-CoV-2 infection expansion of CD8 T cells and reduced expression CXCR3 on T cells in specific post-SARS-CoV-2 infection time points. The authors also conclude that the HIV status attenuates the expansion of antibody secreting cells. The correlative analyses in this study show that low CXCR3 expression on CD8 and CD4 T cells correlates with Covid-19 disease severity, especially in PLWH. The authors did not observe differences in SARS-CoV-2 shedding time frame in the two groups excluding that HIV serostatus plays a role in the emergency of SARS-CoV-2 variants. However, the authors clarify that their PLWH group consisted of mostly ART suppressed participants whose CD4 counts were reasonably high. The study presents the following strengths and limitations

Strengths:

A. A robust longitudinal observational cohort of 124 study participants, 55 of whom were people living with HIV. This cohort was enrolled in KwaZulu-Natal,South Africa during the peak of the pandemic. The participants were followed for up to 5 follow up visits and around 50% of the participants have completed the study.

B. A broad characterization of blood circulating cell subsets by flow cytometry able to identify and characterize T cells, B cells and innate cells.

Weaknesses:

The study design does not include

A. a robust group of HIV-infected individuals with low CD4 counts, as also stated by the authors

B. a group of HIV-uninfected individuals and PLWH with severe COVID-19. As stated in the manuscript the majority of our participants did not progress beyond outcome 4 of the WHO ordinal scale. This is also reflected in the age average of the participants. Limiting the number of participants characterized by severe COVID-19 limits the study to an observational correlative study

C. a control group enrolled at the same time of the study of HIV-uninfected and infected individuals.

D. results that elucidate the mechanisms and functions of immune cells subsets in the contest of COVID-19.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Karim et al have assembled a large cohort of PLWH with acute COVID-19 and well-matched controls. The main finding is that, despite similar clinical and viral (e.g., shedding) outcomes, the immune response to COVID-19 in PLWH differs from the immune response to COVID-19 in HIV uninfected individuals. More specifically, they find that viral loads are comparable between the groups at the time of diagnosis, and that the time to viral clearance (by PCR) is also similar between the two groups. They find that PLWH have higher proportions and also higher absolute number of CD8 cells in the 2-3 weeks after initial infection.

The authors do a wonderful job of clinically characterizing the research participants. I was most impressed by the attention to detail with respect to timing of viral diagnosis as it related to …

Reviewer #3 (Public Review):

Karim et al have assembled a large cohort of PLWH with acute COVID-19 and well-matched controls. The main finding is that, despite similar clinical and viral (e.g., shedding) outcomes, the immune response to COVID-19 in PLWH differs from the immune response to COVID-19 in HIV uninfected individuals. More specifically, they find that viral loads are comparable between the groups at the time of diagnosis, and that the time to viral clearance (by PCR) is also similar between the two groups. They find that PLWH have higher proportions and also higher absolute number of CD8 cells in the 2-3 weeks after initial infection.

The authors do a wonderful job of clinically characterizing the research participants. I was most impressed by the attention to detail with respect to timing of viral diagnosis as it related to symptom onset and specimen collection. I was also impressed by the number of longitudinal samples included in this study.

-

SciScore for 10.1101/2020.11.23.20236828: (What is this?)

Please note, not all rigor criteria are appropriate for all manuscripts.

Table 1: Rigor

Institutional Review Board Statement IRB: Ethical statement and study participants: The study protocol was approved by the University of KwaZulu-Natal Institutional Review Board (approval BREC/00001275/2020).

Consent: Adult patients (>18 years old) presenting either at King Edward VIII or Clairwood Hospitals in Durban, South Africa, between 8 June to 25 September 2020, diagnosed to be SARS-CoV-2 positive as part of their clinical workup and able to provide informed consent were eligible for the study.Randomization not detected. Blinding not detected. Power Analysis not detected. Sex as a biological variable not detected. Table 2: Resources

Software and Algorithms Sentences Resources Cells were then washed … SciScore for 10.1101/2020.11.23.20236828: (What is this?)

Please note, not all rigor criteria are appropriate for all manuscripts.

Table 1: Rigor

Institutional Review Board Statement IRB: Ethical statement and study participants: The study protocol was approved by the University of KwaZulu-Natal Institutional Review Board (approval BREC/00001275/2020).

Consent: Adult patients (>18 years old) presenting either at King Edward VIII or Clairwood Hospitals in Durban, South Africa, between 8 June to 25 September 2020, diagnosed to be SARS-CoV-2 positive as part of their clinical workup and able to provide informed consent were eligible for the study.Randomization not detected. Blinding not detected. Power Analysis not detected. Sex as a biological variable not detected. Table 2: Resources

Software and Algorithms Sentences Resources Cells were then washed twice in PBS and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and stored at 4oC before acquisition on FACSAria Fusion III flow cytometer (BD) and analysed with FlowJo software version 9.9.6 (Tree Star). FlowJosuggested: (FlowJo, RRID:SCR_008520)All tests were performed using Graphpad Prism 8 software. Graphpad Prismsuggested: (GraphPad Prism, RRID:SCR_002798)Results from OddPub: We did not detect open data. We also did not detect open code. Researchers are encouraged to share open data when possible (see Nature blog).

Results from LimitationRecognizer: We detected the following sentences addressing limitations in the study:A limitation of the study is we did not examine antigen specific responses. Further studies, using techniques such as analysis of activation induced marker (AIM) assays for T cells, could add insight into the SARS-CoV-2 specific response [2, 4–7, 47]. We also observed that HIV viremia changes the immune response to COVID-19 in PLWH, including consistently elevated CD8 T cells levels regardless of presence or absence of SARS-CoV-2 RNA or the degree of disease severity (Fig 1), and lack of recovery of CD4 T cells after SARS-CoV-2 clearance (Fig 1). Therefore, effective ART suppression would be expected to play a role in attenuating the effects of HIV infection on COVID-19 immune response. Participants in this study generally showed mild COVID-19 outcomes, despite high frequencies of co-morbidities and HIV infection. Given that COVID-19 infection outcomes were similar in PLWH relative to HIV negative participants, the differences in immune response between the groups may indicate an alternative, as opposed to dysregulated, immunity to SARS-CoV-2 in PLWH. One indication of this is that although CD8 T cells were elevated to abnormally high numbers in PLWH in response to COVID-19, the lack of such expansion correlated with a worse COVID-19 infection outcome in PLWH. The clinical consequences of this remain unclear, but should be considered in the long-term repercussions of COVID-19 infection and the response to a vaccine.

Results from TrialIdentifier: No clinical trial numbers were referenced.

Results from Barzooka: We did not find any issues relating to the usage of bar graphs.

Results from JetFighter: Please consider improving the rainbow (“jet”) colormap(s) used on pages 17, 6 and 7. At least one figure is not accessible to readers with colorblindness and/or is not true to the data, i.e. not perceptually uniform.

Results from rtransparent:- Thank you for including a conflict of interest statement. Authors are encouraged to include this statement when submitting to a journal.

- Thank you for including a funding statement. Authors are encouraged to include this statement when submitting to a journal.

- No protocol registration statement was detected.

-