A computationally designed fluorescent biosensor for D-serine

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

Summary: The reviewers recognize the merits of your work and your efforts to engineer a D-serine selective biosensor. However, they also raise major concerns regarding the experimental design (selection of mutations), methodology and achieved applicability. The reviewers find that the improvement in the selectivity of the engineered construct for the targeted ligand over alternative ligands is modest. They further indicate ambiguities regarding the origin of the ligand-induced fluorescence signal changes of the sensor. Other problematic aspects are the estimation of thermal stabilities and the lack of physiological signals in fluorescence imaging results that could demonstrate applicability to a biological problem.

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

Solute-binding proteins (SBPs) have evolved to balance the demands of ligand affinity, thermostability and conformational change to accomplish diverse functions in small molecule transport, sensing and chemotaxis. Although the ligand-induced conformational changes that occur in SBPs make them useful components in biosensors, they are challenging targets for protein engineering and design. Here we have engineered a D-alanine-specific SBP into a fluorescent biosensor with specificity for the signaling molecule D-serine (D-serFS). This was achieved through binding site and remote mutations that improved affinity ( K D = 6.7 ± 0.5 μM), specificity (40-fold increase vs. glycine), thermostability (Tm = 79 °C) and dynamic range (~14%). This sensor allowed measurement of physiologically relevant changes in D-serine concentration using two-photon excitation fluorescence microscopy in rat brain hippocampal slices. This work illustrates the functional trade-offs between protein dynamics, ligand affinity and thermostability, and how these must be balanced to achieve desirable activities in the engineering of complex, dynamic proteins.

Article activity feed

-

Author Response:

Reviewer #1:

The manuscript “A computationally designed fluorescent biosensor for D-serine" by Vongsouthi et al. reports the engineering of a fluorescent biosensor for D-serine using the D-alanine-specific solute-binding protein from Salmonella enterica (DalS) as a template. The authors engineer a DalS construct that has the enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (ECFP) and the Venus fluorescent protein (Venus) as terminal fusions, which serve as donor and acceptor fluorophores in resonance energy transfer (FRET) experiments. The reporters should monitor a conformational change induced by solute binding through a change of the FRET signal. The authors combine homology-guided rational protein engineering, in-silico ligand docking and computationally guided, stabilizing mutagenesis to transform DalS into a D-serine-specific …

Author Response:

Reviewer #1:

The manuscript “A computationally designed fluorescent biosensor for D-serine" by Vongsouthi et al. reports the engineering of a fluorescent biosensor for D-serine using the D-alanine-specific solute-binding protein from Salmonella enterica (DalS) as a template. The authors engineer a DalS construct that has the enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (ECFP) and the Venus fluorescent protein (Venus) as terminal fusions, which serve as donor and acceptor fluorophores in resonance energy transfer (FRET) experiments. The reporters should monitor a conformational change induced by solute binding through a change of the FRET signal. The authors combine homology-guided rational protein engineering, in-silico ligand docking and computationally guided, stabilizing mutagenesis to transform DalS into a D-serine-specific biosensor applying iterative mutagenesis experiments. Functionality and solute affinity of modified DalS is probed using FRET assays. Vongsouthi et al. assess the applicability of the finally generated D-serine selective biosensor (D-SerFS) in-situ and in-vivo using fluorescence microscopy.

Ionotropic glutamate receptors are ligand-gated ion channels that are importantly involved in brain development, learning, memory and disease. D-serine is a co-agonist of ionotropic glutamate receptors of the NMDA subtype. The modulation of NMDA signalling in the central nervous system through D-serine is hardly understood. Optical biosensors that can detect D-serine are lacking and the development of such sensors, as proposed in the present study, is an important target in biomedical research.

The manuscript is well written and the data are clearly presented and discussed. The authors appear to have succeeded in the development of D-serine-selective fluorescent biosensor. But some questions arose concerning experimental design. Moreover, not all conclusions are fully supported by the data presented. I have the following comments.

- In the homology-guided design two residues in the binding site were mutated to the ones of the D-serine specific homologue NR1 (i.e. F117L and A147S), which lead to a significant increase of affinity to D-serine, as desired. The third residue, however, was mutated to glutamine (Y148Q) instead of the homologous valine (V), which resulted in a substantial loss of affinity to D-serine (Table 1). This "bad" mutation was carried through in consecutive optimization steps. Did the authors also try the homologous Y148V mutation? On page 5 the authors argue that Q instead of V would increase the size of the side chain pocket. But the opposite is true: the side chain of Q is more bulky than the one of V, which may explain the dramatic loss of affinity to D-serine. Mutation Y148V may be beneficial.

Yes, we have previously tested the mutation of position 148 to valine (V). We have now included this data in the paper as Supplementary Information Figure 1 (below). The fluorescence titration showed that the 148V variant displayed poor D-serine specificity compared to Q148 at the same position (the sequence background of the variant was F117L/A147S/D216E/A76D. Thus, Q was superior to V at this position and V was not taken forward for further engineering. In the text, we meant that Q would increase the size of the side chain pocket relative to the wild-type amino acid, Y. We can see that this is unclear and have updated this sentence.

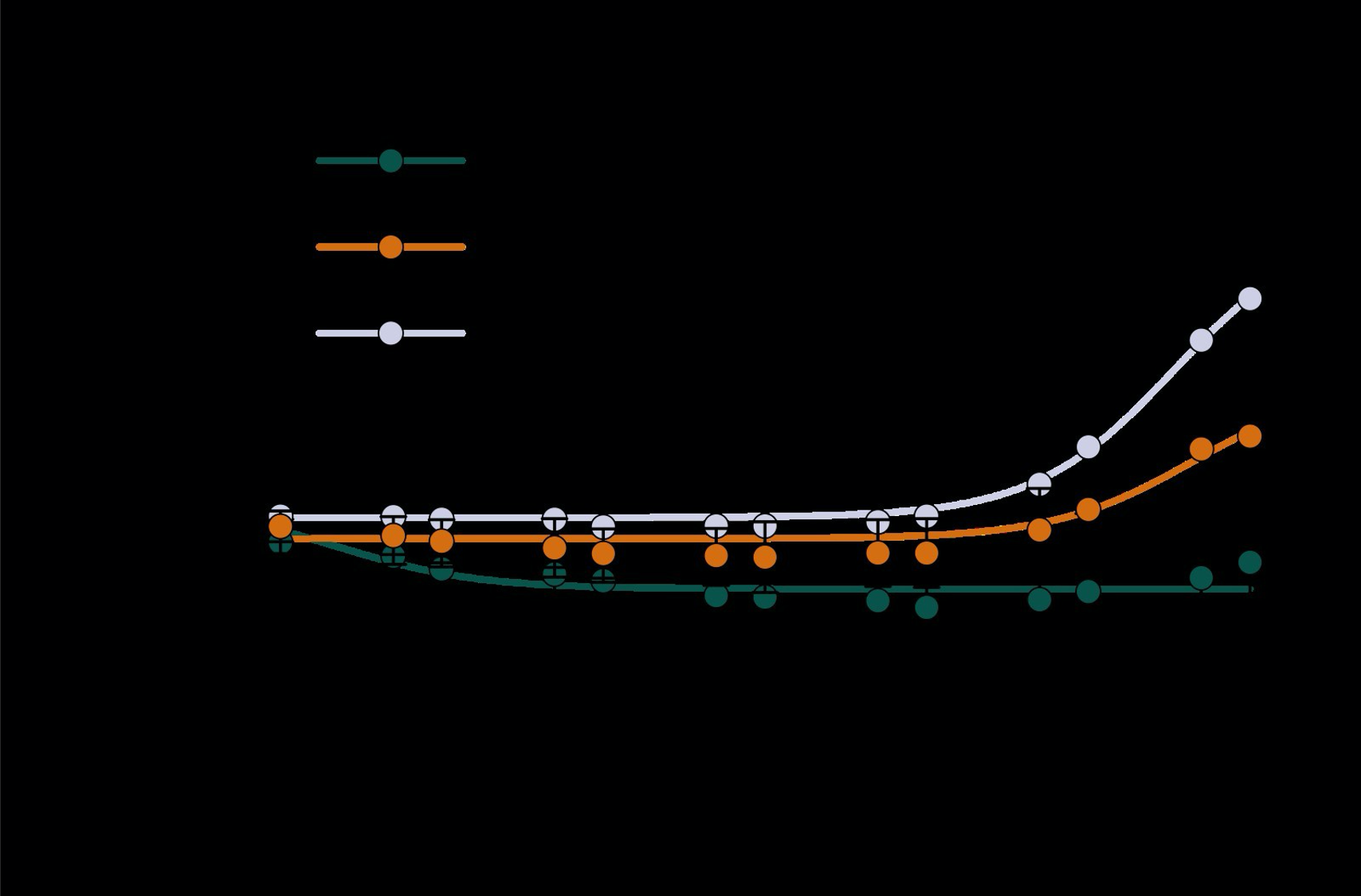

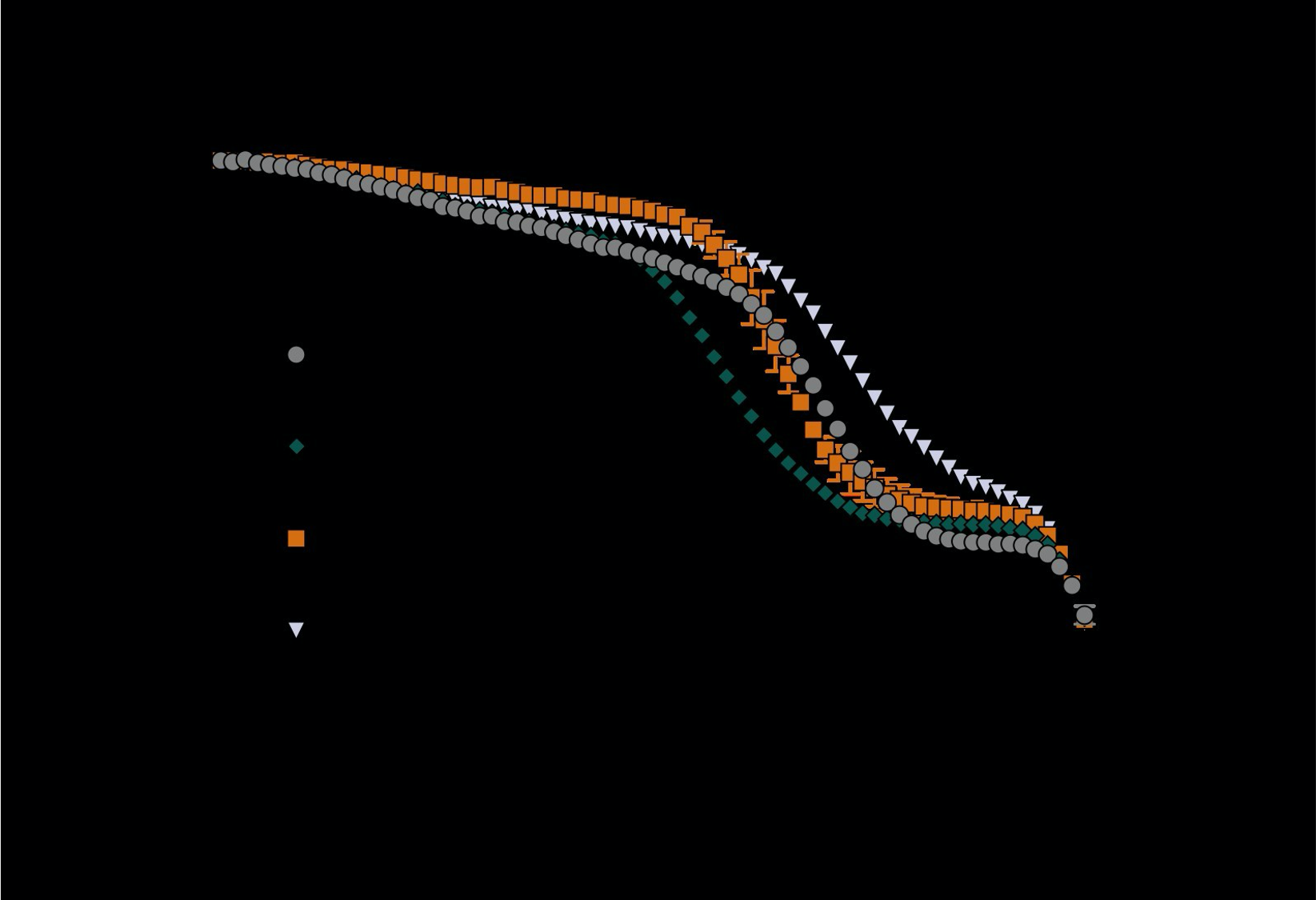

Supplementary Figure 1. Dose-response curves for F117L/A147S/Y148V/D216E/A76D (LSVED) with glycine, D-alanine and D-serine. Values are the (475 nm/530 nm) fluorescence ratio as a percentage of the same ratio for the apo sensor. No significant change is detected in response to glycine. The KD for D-alanine and D-serine are estimated to be > 4000 mM based on fitting curves with the following equation:

- Stabilities of constructs were estimated from melting temperatures (Tm) measured using thermal denaturation probed using the FRET signal of ECFP/Venus fusions. I am not sure if this methodology is appropriate to determine thermal stabilities of DalS and mutants thereof. Thermal unfolding of the fluorescence labels ECFP and Venus and their intrinsic, supposedly strongly temperature-dependent fluorescence emission intensities will interfere. A deconvolution of signals will be difficult. It would be helpful to see raw data from these measurements. All stabilities are reported in terms of deltaTm. What is the absolute Tm of the reference protein DalS? How does the thermal stability of DalS compare to thermal stabilities of ECFP and Venus? A more reliable probe for thermal stability would be the far-UV circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopic signal of DalS without fusions. DalS is a largely helical domain and will show a strong CD signal.

We agree that raw data for the thermal denaturation experiments should be shown and have included this in the supporting information of an updated manuscript (Supplementary Data Figure 7). The data plots ECFP/Venus fluorescence ratio against temperature. When the temperature is increased from 20 to 90 °C, we observe two transitions in the ECFP/Venus fluorescence ratio. The fluorescent proteins are more thermostable than the DalS binding protein, and that temperature transition does not vary (~90 °C); thus, the first transition corresponds to the unfolding of the binding protein and the second transition to the unfolding or loss of fluorescence from the fluorescent proteins. This is an appropriate method for characterising the thermostability of the binding protein in the sensor for two main reasons. Firstly, the calculated melting temperature from the first sigmoidal transition changes upon mutation to the binding protein in a predictable way (e.g. mutations to the binding site/protein core are destabilising), while the second transition occurs consistently at ~ 90 °C. This supports that the first transition corresponds to the unfolding of the binding protein. Secondly, characterising the stability of the binding protein in the context of the full sensor is more relevant to the end-application. Excising the binding domain and testing that in isolation would results in data that are not directly relevant to the sensor. The absolute thermostabilities for all variants can be found in Table 1 of the manuscript.

Supplementary Figure 7. The (475 nm/530 nm) fluorescence ratio as a function of increasing temperature (20 – 90 °C) for key variants in the engineering trajectory of D-serFS. Values are normalised as a percentage of the same ratio for the sensor at 20 °C and are represented as mean ± s.e.m. (n = 3). The first sigmoidal transition in the data changes upon mutation to the binding protein while the second transition begins at ~ 90 °C for all variants. The second transition is not observed in full as the upper temperature limit for the experiment is 90 °C.

- The final construct D-SerFS has a dynamic range of only 7%, which is a low value. It seems that the FRET signal change caused by ligand binding to the construct is weak. Is it sufficient to reliably measure D-serine levels in-situ and in-vivo?

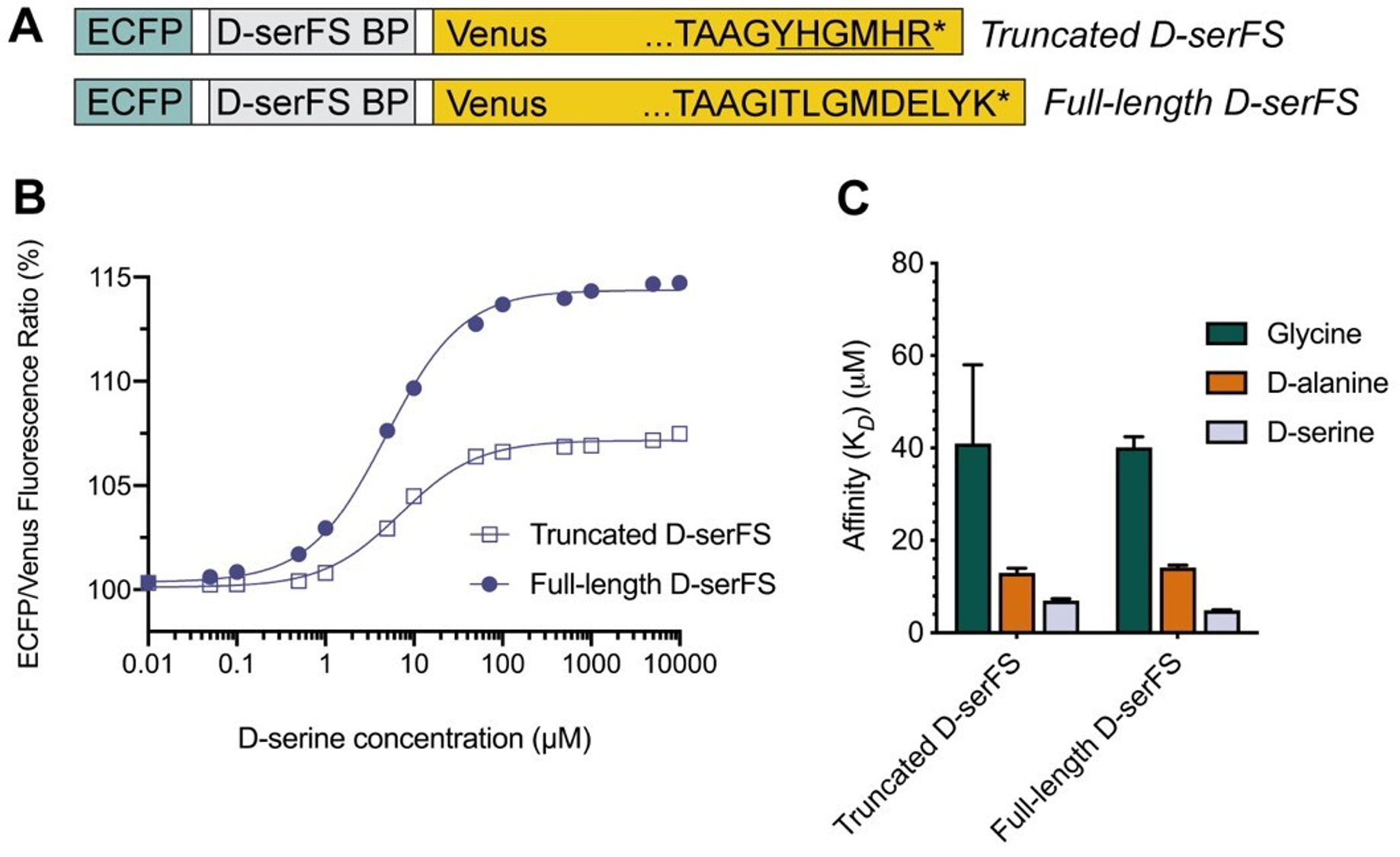

First, we have modified the sensor, which now has a dynamic range of 14.7% (Figure 5, below). The magnitude of the change is reasonable for this sensor class; they function with relative low dynamic range because they are ratiometric sensors, i.e. they are accurate even with low dynamic range because of their ratiometric property. For example, the Gly-sensor GlyFS published in 2018 (Nature Chem. Biol.) has one of the highest dynamic ranges in this sensor class of only ~28%. The Glu sensor described by Okumuto et al., (2005) (PNAS, 102, 8740) has a dynamic range of ~9%. So, the FRET change is not a low value for ratiometric sensors of this class (which have been used very effectively for over a decade). Most importantly, the data from experiments with biological tissue and in vivo (Fig. 6) demonstrate a detectable (and statistically significant) response to changes in D-serine concentration in tissue.

*Figure 5. Characterization of full-length D-serFS. (A) Schematic showing the ECFP (blue), D-serFS binding protein (D-serFS BP; grey) and Venus (yellow) domains in D-serFS. The C-terminal residues of the Venus fluorescent protein sequence are labelled, showing the truncated (top) and full-length (bottom) C-terminal sequences. The underlined amino acids in truncated D-serFS represent residues introduced from the backbone vector sequence during cloning. Represents the STOP codon. (B) Sigmoidal dose response curves for truncated and full-length D-serFS with D-serine (n = 3). Values are the (475 nm/530 nm) fluorescence ratio as a percentage of the same ratio for the apo sensor. (C) Binding affinities (M) determined by fluorescence titration of truncated and full-length D-serFS, for glycine, D-alanine and D-serine (n = 3).

In Figure 5H in-vivo signal changes show large errors and the signal of the positive sample is hardly above error compared to the signal of the control.

We have removed the in vivo data. Regardless, the comment is incorrect. Statistical analysis confirms that there is no significant change in the control (P = 0.08411), whereas the change for the sample with D-serine was significant to P = 0.00998.

“H) ECFP/Venus ratio recorded in vivo in control recordings (left panel, baseline recording first, control recording after 10 minutes; paired two-sided Student’s t-test vs. baseline, t(6) = -2.07,P = 0.08411; n = 6 independent experiments) and during D-serine application (right panel, baseline recording first, second recording after D-serine injection, 1 mM; paired two-sided Student’s t-test vs. baseline, t(3) = -5.85,P = 0.00998; n = 4 independent experiments). Values are mean +- s.e.m. throughout. **P < 0.01.”

Figure 5G is unclear. What does the fluorescence image show?

We have removed the in-vivo data from the manuscript. However, Figure 6 in the original manuscript shows a schematic of how the sensor is applied to the brain for in-vivo experiments (biotin injection, followed by sensor injection and then imaging). The fluorescence image shows the detected Venus fluorescence following pressure loading of the sensor into the brain.

Work presented in this manuscript that assesses functionality and applicability of the developed sensor in-situ and in-vivo is limited compared to the work showing its design. For example, control experiments showing FRET signal changes of the wild-type ECFP-DalS-Venus construct in comparison to the designed D-SerFS would be helpful to assess the outcome.

Indeed, the in situ and in vivo work was never the focus of the study, which is already a large paper. To avoid confusion, the in vivo work is now omitted and the in situ work is present to show proof, in principle, that the sensor can be used to image D-serine. We reiterate – this is a protein engineering paper, not a neuroscience paper.

- The FRET spectra shown in Supplementary Figure 2, which exemplify the measurement of fluorescence ratios of ECFP/Venus, are confusing. I cannot see a significant change of FRET upon application of ligand. The ratios of the peak fluorescence intensities of ECFP and Venus (scanned from the data shown in Supplementary Figure 2) are the same for apo states and the ligand-saturated states. Instead what happens is that fluorescence emission intensities of both the donor and the acceptor bands are reduced upon application of ligand.

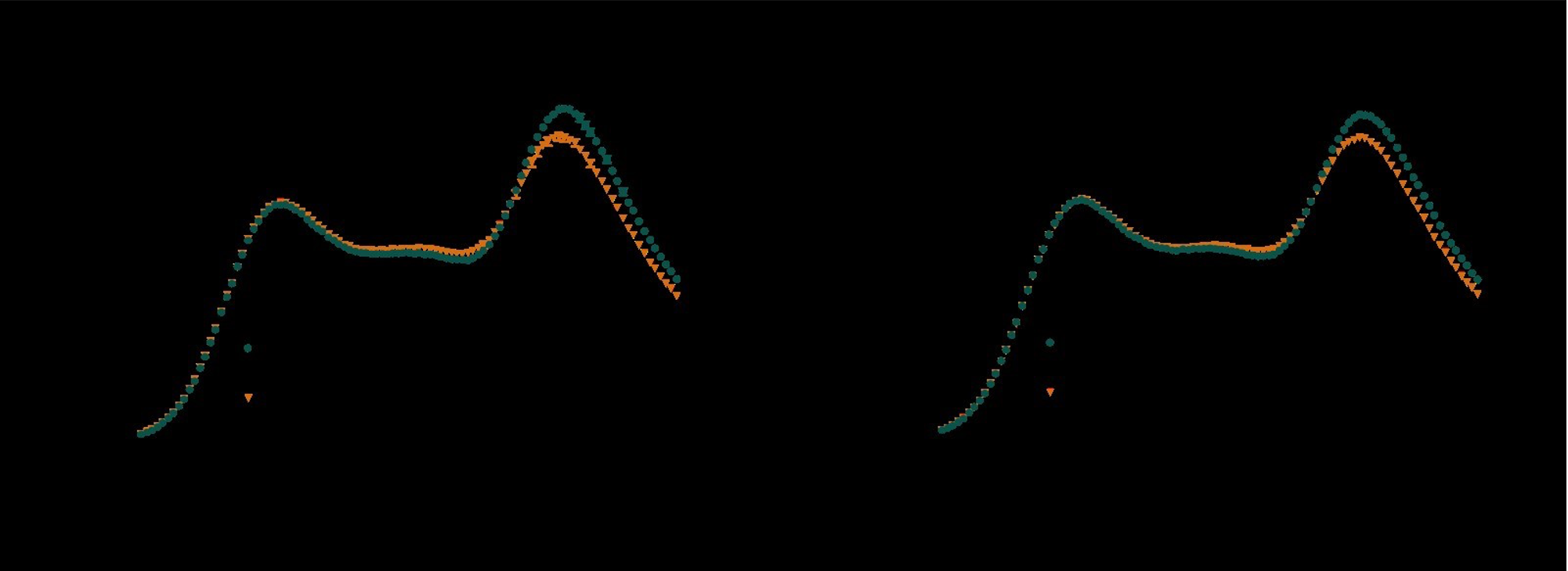

We thank the reviewer for bringing this to our attention. The spectra were not normalised to account for the effect of dilution when saturating with ligand, giving rise to an observed decrease in emission intensity from both ECFP and Venus. We can also see how the figure is hard to interpret when both variants are displayed on the same axes, so we have separated them in an updated figure shown below and normalised the data as a percentage of the maximum emission intensity from ECFP at 475 nm. This has been changed in the supporting information of an updated manuscript. Hopefully it is now clear that there is a ratiometric change upon addition of ligand.

Figure 3. Emission spectra (450 – 550 nm) of (A) LSQED and (B) LSQED-T197Y (LSQEDY) upon excitation of ECFP (lexc = 433 nm), normalised to the maximum emission intensity from ECFP (475 nm). For all sensor variants, the FRET efficiency decreases in response to saturation with D-serine (A, B; orange), leading to decreased emission from Venus (530 nm) relative to ECFP (475 nm). When comparing the apo states of LSQED and LSQEDY (A, B; dark green), it can be seen that the T197Y mutation results in a decreased Venus emission (lower FRET efficiency). This suggests a shift in the apo population of the sensor towards the spectral properties of the saturated, closed state and explains the decreased dynamic range of LSQEDY compared to LSQED. Values are mean ± s.e.m (n = 3).

Reviewer #2:

The authors describe the development and use of a D-Serine sensor based on a periplasmic ligand binding protein (DalS) from Salmonella enterica in conjunction with a FRET readout between enhanced cyan fluorescent protein and Venus fluorescent protein. They rationally identify point mutations in the binding pocket that make the binding protein somewhat more selective for D-serine over glycine and D-alanine. Ligand docking into the binding site, as well as algorithms for increasing the stability, identified further mutants with higher thermostability and higher affinity for D-serine. The combined computational efforts lead to a sensor for D-serine with higher affinity for D-serine (Kd = ~ 7 µM), but also showed affinity for the native D-alanine (Kd = ~ 13 uM) and glycine (Kd = ~40 uM). Molecular simulations were then used to explain how remote mutations identified in the thermostability screen could lead to the observed alteration of ligand affinity. Finally, the D-SerFS was tested in 2P-imaging in hippocampal slices and in anesthetized mice using biotin-straptavidin to anchor exogenously applied purified protein sensor to the brain tissue and pipetting on saturating concentrations of D-serine ligand.

Although presented as the development of a sensor for biology, this work primarily focuses on the application of existing protein engineering techniques to alter the ligand affinity and specificity of a ligand-binding protein domain. The authors are somewhat successful in improving specificity for the desired ligand, but much context is lacking. For any such engineering effort, the end goals should be laid out as explicitly as possible. What sorts of biological signals do they desire to measure? On what length scale? On what time scale? What is known about the concentrations of the analyte and potential competing factors in the tissue? Since the authors do not demonstrate the imaging of any physiological signals with their sensor and do not discuss in detail the nature of the signals they aim to see, the reader is unable to evaluate what effect (if any) all of their protein engineering work had on their progress toward the goal of imaging D-serine signals in tissue.

As a paper describing a combination of protein engineering approaches to alter the ligand affinity and specificity of one protein, it is a relatively complete work. In its current form trying to present a new fluorescent biosensor for imaging biology it is strongly lacking. I would suggest the authors rework the story to exclusively focus on the protein engineering or continue to work on the sensor/imaging/etc until they are able to use it to image some biology.

Additional Major Points:

- There is no discussion of why the authors chose to use non-specific chemical labeling of the tissue with NHS-biotin to anchor their sensor vs. genetic techniques to get cell-type specific expression and localization. There is no high-resolution imaging demonstrating that the sensor is localized where they intended.

We use non-specific chemical labelling for proof-of-concept experiments that show the sensor can respond to changes in D-serine concentration in the extracellular environment of brain tissue. Cell-type specific expression of the sensor is possible based on our previous development of a similar sensor for glycine (Zhang et al., 2018; doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-018-0108-2) where the sensor was expressed by HEK293 cells and neurons, and targeted to the membrane. However, this is beyond the scope of this manuscript. Figure 5G of the original manuscript shows that the sensor (identified by Venus fluorescence) is localized to the area where D-serFS is pressure-loaded into the brain.

- Why does the fluorescence of both the CFP and they YFP decrease upon addition of ligand (see e.g. Supplementary Figure 2)? Were these samples at the same concentration? Is this really a FRET sensor or more of an intensiometric sensor? Is this also true with 2P excitation? How does the Venus fluorescence change when Venus is excited directly? Perhaps fluorescence lifetime measurements could help inform what is happening.

Please see response to major comments from reviewer #1 and Figure 3. We hope this clarifies that the sensor is ratiometric. The sensor behaves similarly under two-photon excitation (2PE) as shown in Figure 5A.

- How reproducible are the spectral differences between LSQED and LSQED-T197Y? Only one trace for each is shown in Supplementary Figure 2 and the differences are very small, but the authors use these data to draw conclusions about the protein open-closed equilibrium.

We have updated this to show data points representing the mean ± s.e.m (n = 3).

- The first three mutations described are arrived upon by aligning DalS (which is more specific for D-Ala) with the NMDA receptor (which binds D-Ser). The authors then mutate two of the ligand pocket positions of DalS to the same amino acid found in NMDAR, but mutate the third position to glutamine instead of valine. I really can't understand why they don't even test Y148V if their goal is a sensor that hopefully detects D-Ser similar to the native NMDAR. I'm sure most readers will have the same confusion.

Please see response to major comments from reviewer #1. Additionally, while the NR1 binding domain of the NMDAR was used a structural guide for rational design of the DalS binding site, the high affinity of the NMDAR for both D-serine and glycine was not desirable in a D-serine-specific sensor.

-

Reviewer #2:

The authors describe the development and use of a D-Serine sensor based on a periplasmic ligand binding protein (DalS) from Salmonella enterica in conjunction with a FRET readout between enhanced cyan fluorescent protein and Venus fluorescent protein. They rationally identify point mutations in the binding pocket that make the binding protein somewhat more selective for D-serine over glycine and D-alanine. Ligand docking into the binding site, as well as algorithms for increasing the stability, identified further mutants with higher thermostability and higher affinity for D-serine. The combined computational efforts lead to a sensor for D-serine with higher affinity for D-serine (Kd = ~ 7 µM), but also showed affinity for the native D-alanine (Kd = ~ 13 uM) and glycine (Kd = ~40 uM). Molecular simulations were then used to …

Reviewer #2:

The authors describe the development and use of a D-Serine sensor based on a periplasmic ligand binding protein (DalS) from Salmonella enterica in conjunction with a FRET readout between enhanced cyan fluorescent protein and Venus fluorescent protein. They rationally identify point mutations in the binding pocket that make the binding protein somewhat more selective for D-serine over glycine and D-alanine. Ligand docking into the binding site, as well as algorithms for increasing the stability, identified further mutants with higher thermostability and higher affinity for D-serine. The combined computational efforts lead to a sensor for D-serine with higher affinity for D-serine (Kd = ~ 7 µM), but also showed affinity for the native D-alanine (Kd = ~ 13 uM) and glycine (Kd = ~40 uM). Molecular simulations were then used to explain how remote mutations identified in the thermostability screen could lead to the observed alteration of ligand affinity. Finally, the D-SerFS was tested in 2P-imaging in hippocampal slices and in anesthetized mice using biotin-straptavidin to anchor exogenously applied purified protein sensor to the brain tissue and pipetting on saturating concentrations of D-serine ligand.

Although presented as the development of a sensor for biology, this work primarily focuses on the application of existing protein engineering techniques to alter the ligand affinity and specificity of a ligand-binding protein domain. The authors are somewhat successful in improving specificity for the desired ligand, but much context is lacking. For any such engineering effort, the end goals should be laid out as explicitly as possible. What sorts of biological signals do they desire to measure? On what length scale? On what time scale? What is known about the concentrations of the analyte and potential competing factors in the tissue? Since the authors do not demonstrate the imaging of any physiological signals with their sensor and do not discuss in detail the nature of the signals they aim to see, the reader is unable to evaluate what effect (if any) all of their protein engineering work had on their progress toward the goal of imaging D-serine signals in tissue.

As a paper describing a combination of protein engineering approaches to alter the ligand affinity and specificity of one protein, it is a relatively complete work. In its current form trying to present a new fluorescent biosensor for imaging biology it is strongly lacking. I would suggest the authors rework the story to exclusively focus on the protein engineering or continue to work on the sensor/imaging/etc until they are able to use it to image some biology.

Additional Major Points:

There is no discussion of why the authors chose to use non-specific chemical labeling of the tissue with NHS-biotin to anchor their sensor vs. genetic techniques to get cell-type specific expression and localization. There is no high-resolution imaging demonstrating that the sensor is localized where they intended.

Why does the fluorescence of both the CFP and they YFP decrease upon addition of ligand (see e.g. Supplementary Figure 2)? Were these samples at the same concentration? Is this really a FRET sensor or more of an intensiometric sensor? Is this also true with 2P excitation? How does the Venus fluorescence change when Venus is excited directly? Perhaps fluorescence lifetime measurements could help inform what is happening.

How reproducible are the spectral differences between LSQED and LSQED-T197Y? Only one trace for each is shown in Supplementary Figure 2 and the differences are very small, but the authors use these data to draw conclusions about the protein open-closed equilibrium.

The first three mutations described are arrived upon by aligning DalS (which is more specific for D-Ala) with the NMDA receptor (which binds D-Ser). The authors then mutate two of the ligand pocket positions of DalS to the same amino acid found in NMDAR, but mutate the third position to glutamine instead of valine. I really can't understand why they don't even test Y148V if their goal is a sensor that hopefully detects D-Ser similar to the native NMDAR. I'm sure most readers will have the same confusion.

-

Reviewer #1:

The manuscript “A computationally designed fluorescent biosensor for D-serine" by Vongsouthi et al. reports the engineering of a fluorescent biosensor for D-serine using the D-alanine-specific solute-binding protein from Salmonella enterica (DalS) as a template. The authors engineer a DalS construct that has the enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (ECFP) and the Venus fluorescent protein (Venus) as terminal fusions, which serve as donor and acceptor fluorophores in resonance energy transfer (FRET) experiments. The reporters should monitor a conformational change induced by solute binding through a change of the FRET signal. The authors combine homology-guided rational protein engineering, in-silico ligand docking and computationally guided, stabilizing mutagenesis to transform DalS into a D-serine-specific biosensor applying …

Reviewer #1:

The manuscript “A computationally designed fluorescent biosensor for D-serine" by Vongsouthi et al. reports the engineering of a fluorescent biosensor for D-serine using the D-alanine-specific solute-binding protein from Salmonella enterica (DalS) as a template. The authors engineer a DalS construct that has the enhanced cyan fluorescent protein (ECFP) and the Venus fluorescent protein (Venus) as terminal fusions, which serve as donor and acceptor fluorophores in resonance energy transfer (FRET) experiments. The reporters should monitor a conformational change induced by solute binding through a change of the FRET signal. The authors combine homology-guided rational protein engineering, in-silico ligand docking and computationally guided, stabilizing mutagenesis to transform DalS into a D-serine-specific biosensor applying iterative mutagenesis experiments. Functionality and solute affinity of modified DalS is probed using FRET assays. Vongsouthi et al. assess the applicability of the finally generated D-serine selective biosensor (D-SerFS) in-situ and in-vivo using fluorescence microscopy.

Ionotropic glutamate receptors are ligand-gated ion channels that are importantly involved in brain development, learning, memory and disease. D-serine is a co-agonist of ionotropic glutamate receptors of the NMDA subtype. The modulation of NMDA signalling in the central nervous system through D-serine is hardly understood. Optical biosensors that can detect D-serine are lacking and the development of such sensors, as proposed in the present study, is an important target in biomedical research.

The manuscript is well written and the data are clearly presented and discussed. The authors appear to have succeeded in the development of D-serine-selective fluorescent biosensor. But some questions arose concerning experimental design. Moreover, not all conclusions are fully supported by the data presented. I have the following comments.

In the homology-guided design two residues in the binding site were mutated to the ones of the D-serine specific homologue NR1 (i.e. F117L and A147S), which lead to a significant increase of affinity to D-serine, as desired. The third residue, however, was mutated to glutamine (Y148Q) instead of the homologous valine (V), which resulted in a substantial loss of affinity to D-serine (Table 1). This "bad" mutation was carried through in consecutive optimization steps. Did the authors also try the homologous Y148V mutation? On page 5 the authors argue that Q instead of V would increase the size of the side chain pocket. But the opposite is true: the side chain of Q is more bulky than the one of V, which may explain the dramatic loss of affinity to D-serine. Mutation Y148V may be beneficial.

Stabilities of constructs were estimated from melting temperatures (Tm) measured using thermal denaturation probed using the FRET signal of ECFP/Venus fusions. I am not sure if this methodology is appropriate to determine thermal stabilities of DalS and mutants thereof. Thermal unfolding of the fluorescence labels ECFP and Venus and their intrinsic, supposedly strongly temperature-dependent fluorescence emission intensities will interfere. A deconvolution of signals will be difficult. It would be helpful to see raw data from these measurements. All stabilities are reported in terms of deltaTm. What is the absolute Tm of the reference protein DalS? How does the thermal stability of DalS compare to thermal stabilities of ECFP and Venus? A more reliable probe for thermal stability would be the far-UV circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopic signal of DalS without fusions. DalS is a largely helical domain and will show a strong CD signal.

The final construct D-SerFS has a dynamic range of only 7%, which is a low value. It seems that the FRET signal change caused by ligand binding to the construct is weak. Is it sufficient to reliably measure D-serine levels in-situ and in-vivo? In Figure 5H in-vivo signal changes show large errors and the signal of the positive sample is hardly above error compared to the signal of the control. Figure 5G is unclear. What does the fluorescence image show? Work presented in this manuscript that assesses functionality and applicability of the developed sensor in-situ and in-vivo is limited compared to the work showing its design. For example, control experiments showing FRET signal changes of the wild-type ECFP-DalS-Venus construct in comparison to the designed D-SerFS would be helpful to assess the outcome.

The FRET spectra shown in Supplementary Figure 2, which exemplify the measurement of fluorescence ratios of ECFP/Venus, are confusing. I cannot see a significant change of FRET upon application of ligand. The ratios of the peak fluorescence intensities of ECFP and Venus (scanned from the data shown in Supplementary Figure 2) are the same for apo states and the ligand-saturated states. Instead what happens is that fluorescence emission intensities of both the donor and the acceptor bands are reduced upon application of ligand.

-

Summary: The reviewers recognize the merits of your work and your efforts to engineer a D-serine selective biosensor. However, they also raise major concerns regarding the experimental design (selection of mutations), methodology and achieved applicability. The reviewers find that the improvement in the selectivity of the engineered construct for the targeted ligand over alternative ligands is modest. They further indicate ambiguities regarding the origin of the ligand-induced fluorescence signal changes of the sensor. Other problematic aspects are the estimation of thermal stabilities and the lack of physiological signals in fluorescence imaging results that could demonstrate applicability to a biological problem.

-