Complex environmental cycles reveal evolution of circadian activity waveform and thermosensitive timeless splicing

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

eLife Assessment

This important study examines how mismatched light and temperature cycles shape Drosophila locomotor timing and temperature-dependent timeless splicing, and leverages long-term early/late selection lines to probe evolutionary plasticity. The strength of evidence is incomplete at present, mainly because startle/masking under step cues could confound the behavioural readouts, and tim's involvement remains correlative. The authors should address masking in the behaviour analyses and provide causal support for tim's role.

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

Abstract

Circadian clocks synchronise physiological and behavioural rhythms to environmental cycles such as light and temperature. In nature, temperature cycles lag light cycles, with the extent of lag varying seasonally. Thus, the extent of this delay is an essential aspect of seasonal cues. Yet, the combined effects of light and temperature cycles on circadian systems remain poorly understood. Using a series of environmental cycles with varying degrees of lag between temperature and light, we examined the response of circadian activity to complex environments and show that morning and evening activity exhibit differential temperature sensitivity in Drosophila melanogaster. We find that the expression of temperature-induced timeless splice variants is modulated by light cycles as well as the degree of lag between temperature and light. We also reveal rhythmic expression of the timeless splicing regulator Psi. Furthermore, we leveraged a laboratory-selection approach to reveal that the differential temperature sensitivity of morning and evening activity evolves upon selection. We observed selection-dependent differences in temporal expression of timeless splice variants thus linking circadian gene splicing to behavioural plasticity. Thus, our integrated behavioural, molecular, and evolutionary approach advances the understanding of how circadian systems integrate seasonal cues.

Article activity feed

-

Author response:

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

This manuscript addresses an important question: how do circadian clocks adjust to a complex rhythmic environment with multiple daily rhythms? The focus is on the temperature and light cycles (TC and LD) and their phase relationship. In nature, TC usually lags the LD cycle, but the phase delay can vary depending on seasonal and daily weather conditions. The authors present evidence that circadian behavior adjusts to different TC/LD phase relationships, that temperature-sensitive tim splicing patterns might underlie some of these responses, and that artificial selection for preferential evening or morning eclosion behavior impacts how flies respond to different LD/TC phase relationship

Strength:

Experiments are conducted on control strains and strains that have …

Author response:

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

This manuscript addresses an important question: how do circadian clocks adjust to a complex rhythmic environment with multiple daily rhythms? The focus is on the temperature and light cycles (TC and LD) and their phase relationship. In nature, TC usually lags the LD cycle, but the phase delay can vary depending on seasonal and daily weather conditions. The authors present evidence that circadian behavior adjusts to different TC/LD phase relationships, that temperature-sensitive tim splicing patterns might underlie some of these responses, and that artificial selection for preferential evening or morning eclosion behavior impacts how flies respond to different LD/TC phase relationship

Strength:

Experiments are conducted on control strains and strains that have been selected in the laboratory for preferential morning or evening eclosion phenotypes. This study is thus quite unique as it allows us to probe whether this artificial selection impacted how animals respond to different environmental conditions, and thus gives hints on how evolution might shape circadian oscillators and their entrainment. The authors focused on circadian locomotor behavior and timeless (tim) splicing because warm and cold-specific transcripts have been described as playing an important role in determining temperature-dependent circadian behavior. Not surprisingly, the results are complex, but there are interesting observations. In particular, the "late" strain appears to be able to adjust more efficiently its evening peak in response to changes in the phase relationship between temperature and light cycles, but the morning peak seems less responsive in this strain. Differences in the circadian pattern of expression of different tim mRNA isoforms are found under specific LD/TC conditions.

We sincerely thank the reviewer for this generous assessment and for recognizing several key strengths of our study. We are particularly gratified that the reviewer values our use of long-term laboratory-selected chronotype lines (350+ generations), which provide a unique evolutionary perspective on how artificial selection reshapes circadian responses to complex LD/TC phase relationships—precisely our core research question.

Weaknesses:

These observations are interesting, but in the absence of specific genetic manipulations, it is difficult to establish a causative link between tim molecular phenotypes and behavior. The study is thus quite descriptive. It would be worth testing available tim splicing mutants, or mutants for regulators of tim splicing, to understand in more detail and more directly how tim splicing determines behavioral adaptation to different phase relationships between temperature and light cycles. Also, I wonder whether polymorphisms in or around tim splicing sites, or in tim splicing regulators, were selected in the early or late strains.

We thank the reviewer for this insightful comment. We agree that our current data do not establish a direct causal link between tim splicing (or Psi) and behaviour, and we appreciate that some of our wording (e.g. “linking circadian gene splicing to behavioural plasticity” or describing tim splicing as a “pivotal node”) may have suggested unintended causal links. In the revision, we will (i) explicitly state in the Abstract, Introduction, and early Discussion that the main aim was to test whether selection for timing of eclosion is accompanied by correlated evolution of temperature‑dependent tim splicing patterns and evening activity plasticity under complex LD/TC regimes, and (ii) consistently describe the molecular findings as correlational and hypothesis‑generating rather than causal. We will also add phrases throughout the text to point the reader more clearly to existing passages where we already emphasize “correlated evolution” and explicitly label our mechanistic ideas as “we speculate” / “we hypothesize” and as future experiments.

We fully agree that studies using tim splicing mutants or manipulations of splicing regulators under in‑sync and out‑of‑sync LD/TC regimes will be essential to ascertain what role tim variants play under such environmental conditions, and we will highlight this as a key future direction. At the same time, we emphasize that the long‑term selection lines provide a complementary perspective to classical mutant analyses by revealing how behavioural and molecular phenotypes can exhibit correlated evolution under a specific, chronobiologically relevant selection pressure (timing of emergence).

Finally, we appreciate the suggestion regarding polymorphisms. Whole‑genome analyses of these lines in a PhD thesis from our group (Ghosh, 2022, unpublished, doctoral dissertation) reveal significant SNPs in intronic regions of timeless in both Early and Late populations, as well as SNPs in CG7879, a gene implicated in alternative mRNA splicing, in the Late line. Because these analyses are ongoing and not yet peer‑reviewed, we do not present them as main results.

I also have a major methodological concern. The authors studied how the evening and morning phases are adjusted under different conditions and different strains. They divided the daily cycle into 12h morning and 12h evening periods, and calculated the phase of morning and evening activity using circular statistics. However, the non-circadian "startle" responses to light or temperature transitions should have a very important impact on phase calculation, and thus at least partially obscure actual circadian morning and evening peak phase changes. Moreover, the timing of the temperature-up startle drifts with the temperature cycles, and will even shift from the morning to the evening portion of the divided daily cycle. Its amplitude also varies as a function of the LD/TC phase relationship. Note that the startle responses and their changes under different conditions will also affect SSD quantifications.

We thank the reviewer for this perceptive methodological concern, which we had anticipated and systematically quantified but had not included in the original submission. The reviewer is absolutely correct that non-circadian startle responses to zeitgeber transitions could confound both circular phase (CoM) calculations and SSD quantifications, particularly as TC drift creates shifting startle locations across morning/evening windows.

We will be including startle response quantification (previously conducted but unpublished) as new a Supplementary figure, systematically measuring SSD in 1-hour windows immediately following each of the four environmental transitions (lights-ON, lights-OFF, temperature rise and temperature fall) across all six LDTC regimes (2-12hr TC-LD lags) for all 12 selection lines (early1-4, control1-4, late1-4).

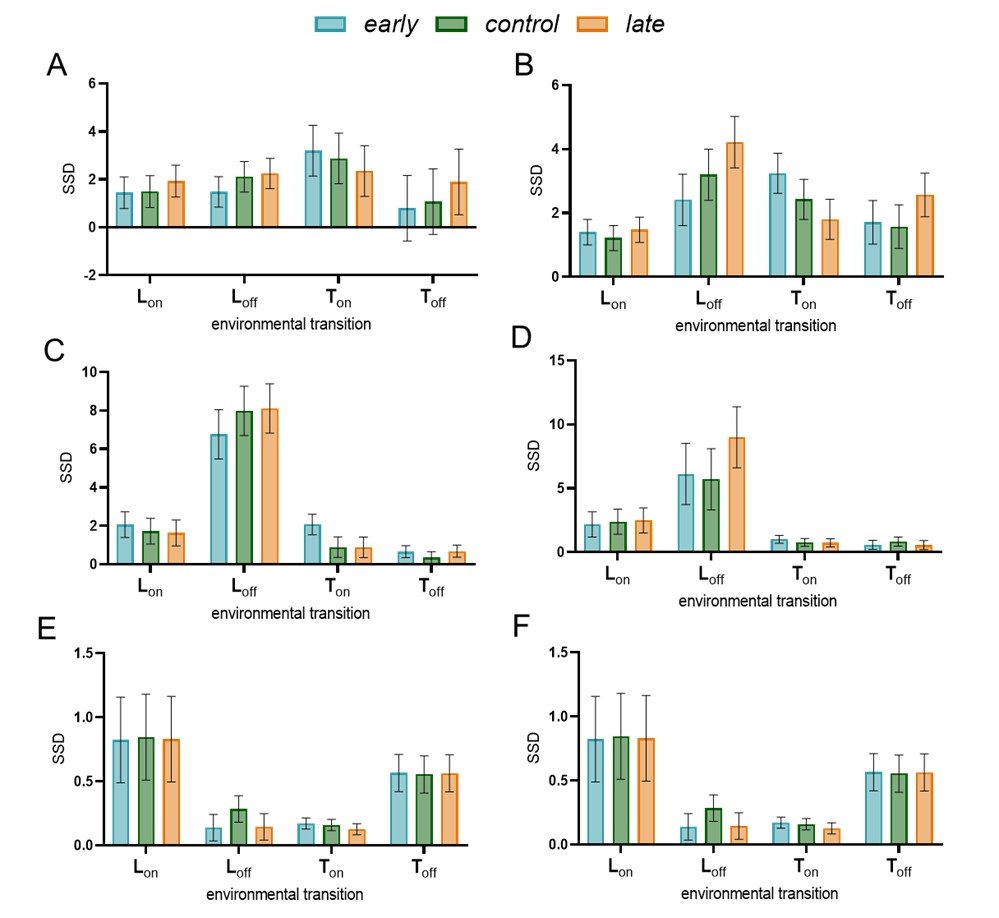

Author response image 1.

Startle responses in selection lines under LDTC regimes: SSD calculated to assess startle response to each of the transitions (1-hour window after the transition used for calculations). Error bars are 95% Tukey’s confidence intervals for the main effect of selection in a two-factor ANOVA design with block as a random factor. Non-overlapping error bars indicate significant differences among the values. SSD values between in-sync and out-of-sync regimes for a range of phase relationships between LD and TC cycles (A) LDTC 2-hr, (B) LDTC 4-hr, (C) LDTC 6-hr, (D) LDTC 8-hr, (E) LDTC 10-hr, (F) LDTC 12-hr.

Key findings directly addressing the reviewer's concerns:

(1) Morning phase advances in LDTC 8-12hr regimes are explained by quantified nocturnal startle activity around temperature rise transitions occurring within morning windows. Critically, these startles show no selection line differences, confirming they represent equivalent non-circadian confounds across lines.

(2) Early selection lines exhibit significantly heightened startle responses specifically to temperature rise in LDTC 4hr and 6hr regimes (early > control ≥ late), demonstrating that startle responses themselves exhibit correlated evolution with emergence timing—an important novel finding that strengthens our evolutionary story.

(3) Startle responses differed among selection lines only for the temperature rise transition under two of the regimes used, LDTC 4 hr and 6 hr regimes. Under LDTC 4 hr, temperature rise transition falls in the morning window and despite early having significantly greater startle than late, the overall morning SSD (over 12 hours morning window) did not differ significantly among the selection lines for this regime. Thus, eliminating the startle window would make the selection lines more similar to one another. On the other hand, under LDTC 6 hour regime, the startle response to temperature rise falls in the evening 12 hour window. In this case too, early showed higher startle than control and late. A higher startle in early would thus, contribute to the observed differences among selection lines. We agree with the reviewer that eliminating this startle peak would lead to a clearer interpretation of the change in circadian evening activity.

We deliberately preserved all behavioural data without filtering out startle windows since it would require arbitrary cutoffs like 1 hr, 2 hr or 3 hours post transitions or until the startle peaks declines in different selection lines under different regimes. In the revised version, we will add complementary analyses excluding the startle windows to obtain mean phase and SSD values which are unaffected by the startle responses.

For the circadian phase, these issues seem, for example, quite obvious for the morning peak in Figure 1. According to the phase quantification on panel D, there is essentially no change in the morning phase when the temperature cycle is shifted by 6 hours compared to the LD cycle, but the behavior trace on panel B clearly shows a phase advance of morning anticipation. Comparison between the graphs on panels C and D also indicates that there are methodological caveats, as they do not correlate well.

Because of the various masking effects, phase quantification under entrainment is a thorny problem in Drosophila. I would suggest testing other measurements of anticipatory behavior to complement or perhaps supersede the current behavior analysis. For example, the authors could employ the anticipatory index used in many previous studies, measure the onset of morning or evening activity, or, if more reliable, the time at which 50% of anticipatory activity is reached. Termination of activity could also be considered. Interestingly, it seems there are clear effects on evening activity termination in Figure 3. All these methods will be impacted by startle responses under specific LD/TC phase relationships, but their combination might prove informative.

We agree that phase quantification under entrained conditions in Drosophila is challenging and that anticipatory indices, onset/offset measures, and T50 metrics each have particular strengths and weaknesses. In designing our analysis, we chose to avoid metrics that require arbitrary or subjective criteria (e.g. defining activity thresholds or durations for anticipation, or visually marking onset/offset), because these can substantially affect the estimated phase and reduce comparability across regimes and genotypes. Instead, we used two fully quantitative, parameter-free measures applied to the entire waveform within defined windows: (i) SSD to capture waveform change in shape/amplitude and (ii) circular mean phase of activity (CoM) restricted to the 12 h morning and 12 h evening windows. By integrating over the entire window, these measures are less sensitive to the exact choice of threshold and to short-lived, high-amplitude startles at transitions, and they treat all bins within the window in a consistent, reproducible way across all LDTC regimes and lines. Panels C (SSD) and D (CoM) are intentionally complementary, not redundant: SSD reflects how much the waveform changes in shape and amplitude, whereas CoM reflects the timing of the center of mass of activity. Under conditions where masking alters amplitude and introduces short-lived bouts without a major shift of the main peak, it is expected that SSD and CoM will not correlate linearly across regimes.

We will be including a detailed calculation of how CoM is obtained in our methods for the revised version.

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors aimed to dissect the plasticity of circadian outputs by combining evolutionary biology with chronobiology. By utilizing Drosophila strains selected for "Late" and "Early" adult emergence, they sought to investigate whether selection for developmental timing co-evolves with plasticity in daily locomotor activity. Specifically, they examined how these diverse lines respond to complex, desynchronized environmental cues (temperature and light cycles) and investigated the molecular role of the splicing factor Psi and timeless isoforms in mediating this plasticity.

Major strengths and weaknesses:

The primary strength of this work is the novel utilization of long-term selection lines to address fundamental questions about how organisms cope with complex environmental cues. The behavioral data are compelling, clearly demonstrating that "Late" and "Early" flies possess distinct capabilities to track temperature cycles when they are desynchronized from light cycles.

We sincerely thank the reviewer for this enthusiastic recognition of our study's core strengths. We are particularly gratified that the reviewer highlights our novel use of long-term selection lines (350+ generations) as the primary strength, enabling us to address fundamental evolutionary questions about circadian plasticity under complex environmental cues. We thank them for identifying our behavioral data as compelling (Figs 1, 3), which robustly demonstrate selection-driven divergence in temperature cycle tracking.

However, a significant weakness lies in the causal links proposed between the molecular findings and these behavioral phenotypes. The molecular insights (Figures 2, 4, 5, and 6) rely on mRNA extracted from whole heads. As head tissue is dominated by photoreceptor cells and glia rather than the specific pacemaker neurons (LNv, LNd) driving these behaviors, this approach introduces a confound. Differential splicing observed here may reflect the state of the compound eye rather than the central clock circuit, a distinction highlighted by recent studies (e.g., Ma et al., PNAS 2023).

We thank the reviewer for highlighting this important methodological consideration. We fully agree that whole-head extracts do not provide spatial resolution to distinguish central pacemaker neurons (~100-200 total) from compound eyes and glia, and that cell-type-specific profiling represents the critical next experimental step. As mentioned in our response to Reviewer 1, we appreciate the issue with our phrasing and will be revising it accordingly to more clearly describe that we do not claim any causal connections between expression of the tim splice variants in particular circadian neurons and their contribution of the phenotype observed.

We chose whole-head extracts for practical reasons aligned with our study's specific goals:

(1) Fly numbers: Our artificially selected populations are maintained at large numbers (~1000s per line). Whole-head extracts enabled sampling ~150 flies per time point = ~600 flies per genotype per environmental, providing means to faithfully sample the variation that may exist in such randomly mating populations.

(2) Established method for characterizing splicing patterns: The majority of temperature-dependent period/timeless splicing studies have successfully used whole-head extracts (Majercak et al., 1999; Shakhmantsir et al., 2018; Martin Anduaga et al., 2019) to characterize splicing dynamics under novel conditions.

(3) Novel environmental regimes: Our primary molecular contribution was documenting timeless splicing patterns under previously untested LDTC phase relationships (TC 2-12hr lags relative to LD) and testing whether these exhibit selection-dependent differences consistent with behavioral divergence.

Furthermore, while the authors report that Psi mRNA loses rhythmicity under out-of-sync conditions, this correlation does not definitively prove that Psi oscillation is required for the observed splicing patterns or behavioral plasticity. The amplitude of the reported Psi rhythm is also low (~1.5 fold) and variable, raising questions about its functional significance in the absence of manipulation experiments (such as constitutive expression) to test causality.

We thank the reviewer for this insightful comment and appreciate that our phrasing has been misleading. We will especially pay attention to this issue, raised by two reviewers, and clearly highlight our results as correlated evolution and hypothesis-generating.

We appreciate the reviewer highlighting these points and would like to draw attention to the following points in our Discussion section:

“Psi and levels of tim-cold and tim-sc (Foley et al., 2019). We observe that this correlation is most clearly upheld under temperature cycles wherein tim-medium and Psi peak in-phase while the cold-induced transcripts start rising when Psi falls (Figure 8A1&2). Under LDTC in-sync conditions this relationship is weaker, even though Psi is rhythmic, potentially due to light-modulated factors influencing timeless splicing (Figure 8B1&2). This is in line with Psi’s established role in regulating activity phasing under TC 12:12 but not LD 12:12 (Foley et al., 2019). This is also supported by the fact that while tim-medium and tim-cold are rhythmic under LD 12:12 (Shakhmantsir et al., 2018), Psi is not (datasets from Kuintzle et al., 2017; Rodriguez et al., 2013). Assuming this to be true across genetic backgrounds and sexes and combined with our similar findings for these three transcripts under LDTC out-of-sync (Figure 2B3, D3&E3), we speculate that Psi rhythmicity may not be essential for tim-medium or tim-cold rhythmicity especially under conditions wherein light cycles are present along with temperature cycles (Figure 8C1&2). Our study opens avenues for future experiments manipulating PSI expression under varying light-temperature regimes to dissect its precise regulatory interactions. We hypothesize that flies with Psi knocked down in the clock neurons should exhibit a less pronounced shift of the evening activity under the range LDTC out-of-sync conditions for which activity is assayed in our study. On the other hand, its overexpression should cause larger delays in response to delayed temperature cycles due to the increased levels of tim-medium translating into delay in TIM protein accumulation.”

Appraisal of aims and conclusions:

The authors successfully demonstrate the co-evolution of emergence timing and activity plasticity, achieving their aim on the behavioral level. However, the conclusion that the specific molecular mechanism involves the loss of Psi rhythmicity driving timeless splicing changes is not yet fully supported by the data. The current evidence is correlative, and without spatial resolution (specific clock neurons) or causal manipulation, the mechanistic model remains speculative.

This study is likely to be of significant interest to the chronobiology and evolutionary biology communities as it highlights the "enhanced plasticity" of circadian clocks as an adaptive trait. The findings suggest that plasticity to phase lags - common in nature where temperature often lags light - may be a key evolutionary adaptation. Addressing the mechanistic gaps would significantly increase the utility of these findings for understanding the molecular basis of circadian plasticity.

Thank you for this thoughtful appraisal affirming our successful demonstration of co-evolution between emergence timing and circadian activity plasticity.

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

This study attempts to mimic in the laboratory changing seasonal phase relationships between light and temperature and determine their effects on Drosophila circadian locomotor behavior and on the underlying splicing patterns of a canonical clock gene, timeless. The results are then extended to strains that have been selected over many years for early or late circadian phase phenotypes.

Strengths:

A lot of work, and some results showing that the phasing of behavioural and molecular phenotypes is slightly altered in the predicted directions in the selected strains.

We thank the reviewer for acknowledging the substantial experimental effort across 7 environmental regimes (6 LDTC phase relationships + LDTC in-phase), 12 replicate populations (early1-4, control1-4, late1-4), and comprehensive behavioural + molecular phenotyping.

Weaknesses:

The experimental conditions are extremely artificial, with immediate light and temperature transitions compared to the gradual changes observed in nature. Studies in the wild have shown how the laboratory reveals artifacts that are not observed in nature. The behavioural and molecular effects are very small, and some of the graphs and second-order analyses of the main effects appear contradictory. Consequently, the Discussion is very speculative as it is based on such small laboratory effects.

We thank the reviewer for these important points regarding ecological validity, effect sizes, and interpretation scope.

(1) Behavioural effects are robust across population replicates in selection lines (not small/weak)

Our study assayed 12 populations total (4 replicate populations each of early, control, and late selection lines) under 7 LDTC regimes. Critically, selection effects were consistent across all 4 replicate populations within each selection line for every condition tested. In these randomly mating large populations, the mixed model ANOVA reveals highly significant selection×regime interactions [F(5,45)=4.1, p=0.003; Fig 3E, Table S2], demonstrating strong, replicated evolutionary divergence in evening temperature sensitivity.

(2) Molecular effects test critical evolutionary hypothesis

As stated in our Introduction, "selection can shape circadian gene splicing and temperature responsiveness" (Low et al., 2008, 2012). Our laboratory-selected chronotype populations—known to exhibit evolved temperature responsiveness (Abhilash et al., 2019, 2020; Nikhil et al., 2014; Vaze et al., 2012)—provide an apt system to test whether selection for temporal niche leads to divergence in timeless splicing. With ~600 heads per environmental regime per selection line, we detect statistically robust, selection line-specific temporal profiles [early4 advanced timeless phase (Fig 4A4); late4 prolonged tim-cold (Fig 5A4); significant regime×selection×time interactions (Tables S3-S5)], providing initial robust evidence of correlated molecular evolution under novel LDTC regimes.

(3) Systematic design fills critical field gap

Artificial conditions like LD/DD have been useful in revealing fundamental zeitgeber principles. Our systematic 2-12hr TC-LD lags directly implement Pittendrigh & Bruce (1959) + Oda & Friesen (2011) validated design, which discuss how such experimental designs can provide a more comprehensive understanding of zeitgeber integration compared to studies with only one phase jump between two zeitgebers.

(4) Ramping regimes as essential next step

Gradual ramping regimes better mimic nature and represent critical future experiments. New Discussion addition in the revised version: "Ramping LDTC regimes can test whether selection-specific zeitgeber hierarchy persists under naturalistic gradients." While ramping experiments are essential, we would like to emphasize that we aimed to use this experimental design as a tool to test if evening activity exhibits greater temperature sensitivity and if this property of the circadian system can undergo correlated evolution upon selection for timing of eclosion/emergence.

(5) New startle quantification addresses masking

Our startle quantification (which will be added as a new supplementary figure) confirms circadian evening tracking persists despite quantified, selection-independent masking in most of the regimes.

-

eLife Assessment

This important study examines how mismatched light and temperature cycles shape Drosophila locomotor timing and temperature-dependent timeless splicing, and leverages long-term early/late selection lines to probe evolutionary plasticity. The strength of evidence is incomplete at present, mainly because startle/masking under step cues could confound the behavioural readouts, and tim's involvement remains correlative. The authors should address masking in the behaviour analyses and provide causal support for tim's role.

-

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

This manuscript addresses an important question: how do circadian clocks adjust to a complex rhythmic environment with multiple daily rhythms? The focus is on the temperature and light cycles (TC and LD) and their phase relationship. In nature, TC usually lags the LD cycle, but the phase delay can vary depending on seasonal and daily weather conditions. The authors present evidence that circadian behavior adjusts to different TC/LD phase relationships, that temperature-sensitive tim splicing patterns might underlie some of these responses, and that artificial selection for preferential evening or morning eclosion behavior impacts how flies respond to different LD/TC phase relationship

Strength:

Experiments are conducted on control strains and strains that have been selected in the laboratory for …

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

This manuscript addresses an important question: how do circadian clocks adjust to a complex rhythmic environment with multiple daily rhythms? The focus is on the temperature and light cycles (TC and LD) and their phase relationship. In nature, TC usually lags the LD cycle, but the phase delay can vary depending on seasonal and daily weather conditions. The authors present evidence that circadian behavior adjusts to different TC/LD phase relationships, that temperature-sensitive tim splicing patterns might underlie some of these responses, and that artificial selection for preferential evening or morning eclosion behavior impacts how flies respond to different LD/TC phase relationship

Strength:

Experiments are conducted on control strains and strains that have been selected in the laboratory for preferential morning or evening eclosion phenotypes. This study is thus quite unique as it allows us to probe whether this artificial selection impacted how animals respond to different environmental conditions, and thus gives hints on how evolution might shape circadian oscillators and their entrainment. The authors focused on circadian locomotor behavior and timeless (tim) splicing because warm and cold-specific transcripts have been described as playing an important role in determining temperature-dependent circadian behavior. Not surprisingly, the results are complex, but there are interesting observations. In particular, the "late" strain appears to be able to adjust more efficiently its evening peak in response to changes in the phase relationship between temperature and light cycles, but the morning peak seems less responsive in this strain. Differences in the circadian pattern of expression of different tim mRNA isoforms are found under specific LD/TC conditions.

Weaknesses:

These observations are interesting, but in the absence of specific genetic manipulations, it is difficult to establish a causative link between tim molecular phenotypes and behavior. The study is thus quite descriptive. It would be worth testing available tim splicing mutants, or mutants for regulators of tim splicing, to understand in more detail and more directly how tim splicing determines behavioral adaptation to different phase relationships between temperature and light cycles. Also, I wonder whether polymorphisms in or around tim splicing sites, or in tim splicing regulators, were selected in the early or late strains.

I also have a major methodological concern. The authors studied how the evening and morning phases are adjusted under different conditions and different strains. They divided the daily cycle into 12h morning and 12h evening periods, and calculated the phase of morning and evening activity using circular statistics. However, the non-circadian "startle" responses to light or temperature transitions should have a very important impact on phase calculation, and thus at least partially obscure actual circadian morning and evening peak phase changes. Moreover, the timing of the temperature-up startle drifts with the temperature cycles, and will even shift from the morning to the evening portion of the divided daily cycle. Its amplitude also varies as a function of the LD/TC phase relationship. Note that the startle responses and their changes under different conditions will also affect SSD quantifications.

For the circadian phase, these issues seem, for example, quite obvious for the morning peak in Figure 1. According to the phase quantification on panel D, there is essentially no change in the morning phase when the temperature cycle is shifted by 6 hours compared to the LD cycle, but the behavior trace on panel B clearly shows a phase advance of morning anticipation. Comparison between the graphs on panels C and D also indicates that there are methodological caveats, as they do not correlate well.

Because of the various masking effects, phase quantification under entrainment is a thorny problem in Drosophila. I would suggest testing other measurements of anticipatory behavior to complement or perhaps supersede the current behavior analysis. For example, the authors could employ the anticipatory index used in many previous studies, measure the onset of morning or evening activity, or, if more reliable, the time at which 50% of anticipatory activity is reached. Termination of activity could also be considered. Interestingly, it seems there are clear effects on evening activity termination in Figure 3. All these methods will be impacted by startle responses under specific LD/TC phase relationships, but their combination might prove informative.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors aimed to dissect the plasticity of circadian outputs by combining evolutionary biology with chronobiology. By utilizing Drosophila strains selected for "Late" and "Early" adult emergence, they sought to investigate whether selection for developmental timing co-evolves with plasticity in daily locomotor activity. Specifically, they examined how these diverse lines respond to complex, desynchronized environmental cues (temperature and light cycles) and investigated the molecular role of the splicing factor Psi and timeless isoforms in mediating this plasticity.

Major strengths and weaknesses:

The primary strength of this work is the novel utilization of long-term selection lines to address fundamental questions about how organisms cope with complex environmental cues. The behavioral data …

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Summary:

The authors aimed to dissect the plasticity of circadian outputs by combining evolutionary biology with chronobiology. By utilizing Drosophila strains selected for "Late" and "Early" adult emergence, they sought to investigate whether selection for developmental timing co-evolves with plasticity in daily locomotor activity. Specifically, they examined how these diverse lines respond to complex, desynchronized environmental cues (temperature and light cycles) and investigated the molecular role of the splicing factor Psi and timeless isoforms in mediating this plasticity.

Major strengths and weaknesses:

The primary strength of this work is the novel utilization of long-term selection lines to address fundamental questions about how organisms cope with complex environmental cues. The behavioral data are compelling, clearly demonstrating that "Late" and "Early" flies possess distinct capabilities to track temperature cycles when they are desynchronized from light cycles.

However, a significant weakness lies in the causal links proposed between the molecular findings and these behavioral phenotypes. The molecular insights (Figures 2, 4, 5, and 6) rely on mRNA extracted from whole heads. As head tissue is dominated by photoreceptor cells and glia rather than the specific pacemaker neurons (LNv, LNd) driving these behaviors, this approach introduces a confound. Differential splicing observed here may reflect the state of the compound eye rather than the central clock circuit, a distinction highlighted by recent studies (e.g., Ma et al., PNAS 2023).

Furthermore, while the authors report that Psi mRNA loses rhythmicity under out-of-sync conditions, this correlation does not definitively prove that Psi oscillation is required for the observed splicing patterns or behavioral plasticity. The amplitude of the reported Psi rhythm is also low (~1.5 fold) and variable, raising questions about its functional significance in the absence of manipulation experiments (such as constitutive expression) to test causality.

Appraisal of aims and conclusions:

The authors successfully demonstrate the co-evolution of emergence timing and activity plasticity, achieving their aim on the behavioral level. However, the conclusion that the specific molecular mechanism involves the loss of Psi rhythmicity driving timeless splicing changes is not yet fully supported by the data. The current evidence is correlative, and without spatial resolution (specific clock neurons) or causal manipulation, the mechanistic model remains speculative.

This study is likely to be of significant interest to the chronobiology and evolutionary biology communities as it highlights the "enhanced plasticity" of circadian clocks as an adaptive trait. The findings suggest that plasticity to phase lags - common in nature where temperature often lags light - may be a key evolutionary adaptation. Addressing the mechanistic gaps would significantly increase the utility of these findings for understanding the molecular basis of circadian plasticity.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

This study attempts to mimic in the laboratory changing seasonal phase relationships between light and temperature and determine their effects on Drosophila circadian locomotor behavior and on the underlying splicing patterns of a canonical clock gene, timeless. The results are then extended to strains that have been selected over many years for early or late circadian phase phenotypes.

Strengths:

A lot of work, and some results showing that the phasing of behavioral and molecular phenotypes is slightly altered in the predicted directions in the selected strains.

Weaknesses:

The experimental conditions are extremely artificial, with immediate light and temperature transitions compared to the gradual changes observed in nature. Studies in the wild have shown how the laboratory reveals artifacts that …

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

This study attempts to mimic in the laboratory changing seasonal phase relationships between light and temperature and determine their effects on Drosophila circadian locomotor behavior and on the underlying splicing patterns of a canonical clock gene, timeless. The results are then extended to strains that have been selected over many years for early or late circadian phase phenotypes.

Strengths:

A lot of work, and some results showing that the phasing of behavioral and molecular phenotypes is slightly altered in the predicted directions in the selected strains.

Weaknesses:

The experimental conditions are extremely artificial, with immediate light and temperature transitions compared to the gradual changes observed in nature. Studies in the wild have shown how the laboratory reveals artifacts that are not observed in nature. The behavioral and molecular effects are very small, and some of the graphs and second-order analyses of the main effects appear contradictory. Consequently, the Discussion is very speculative as it is based on such small laboratory effects

-

-

-