An in vitro human vessel model to study Neisseria meningitidis colonization and vascular damages

Curation statements for this article:-

Curated by eLife

eLife Assessment

The authors develop an important microfluidic microvascular model called "Vessel-on-Chip", which they use to study Neisseria meningitidis interactions within this in vitro vascular system. Compelling evidence shows that the fabricated channels are lined by endothelial cells, and these can be colonized by N. meningitidis that in turn triggers neutrophil recruitment. This model has advantages over the human skin xenograft mouse model, which requires complex surgical techniques, however, it also carries limitations in that only endothelial cells and supplied specific immune cells in the microfluidics are present, while true vasculature contains a number of other cell types including smooth muscle cells, pericytes, and components of the immune system.

[Editors' note: this paper was reviewed by Review Commons.]

This article has been Reviewed by the following groups

Discuss this preprint

Start a discussion What are Sciety discussions?Listed in

- Evaluated articles (eLife)

- Evaluated articles (Review Commons)

Abstract

Systemic infections leading to sepsis are life-threatening conditions that remain difficult to treat, and the limitations of current experimental models hamper the development of innovative therapies. Animal models are constrained by species-specific differences, while 2D cell culture systems fail to capture the complex pathophysiology of infection. To overcome these limitations, we developed a laser photoablation-generated, three-dimensional microfluidic model of meningococcal vascular colonization, a human-specific bacterium that causes sepsis and meningitis. Laser photoablation-generated hydrogel engineering allows the reproduction of vascular networks that are major infection target sites, and this model provides the relevant microenvironment reproducing the physiological endothelial integrity and permeability in vitro. By comparing with a human-skin xenograft mouse model, we show that the model system not only replicates in vivo key features of the infection, but also enables quantitative assessment with a higher spatiotemporal resolution of bacterial microcolony growth, endothelial cytoskeleton rearrangement, vascular E-selectin expression, and neutrophil response upon infection. Our device thus provides a robust solution bridging the gap between animal and 2D cellular models, paving the way for a better understanding of disease progression and developing innovative therapeutics.

Article activity feed

-

-

-

-

eLife Assessment

The authors develop an important microfluidic microvascular model called "Vessel-on-Chip", which they use to study Neisseria meningitidis interactions within this in vitro vascular system. Compelling evidence shows that the fabricated channels are lined by endothelial cells, and these can be colonized by N. meningitidis that in turn triggers neutrophil recruitment. This model has advantages over the human skin xenograft mouse model, which requires complex surgical techniques, however, it also carries limitations in that only endothelial cells and supplied specific immune cells in the microfluidics are present, while true vasculature contains a number of other cell types including smooth muscle cells, pericytes, and components of the immune system.

[Editors' note: this paper was reviewed by Review Commons.]

-

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

The work by Pinon et al describes the generation of a microvascular model to study Neisseria meningitidis interactions with blood vessels. The model uses a novel and relatively high throughput fabrication method that allows full control over the geometry of the vessels. The model is well characterized from the vascular standpoint and shows improvements when exposed to flow. The authors show that Neisseria binds to the 3D model in a similar geometry that in the animal xenograft model, induces an increase in permeability short after bacterial perfusion, and endothelial cytoskeleton rearrangements including a honeycomb actin structure. Finally, the authors show neutrophil recruitment to bacterial microcolonies and phagocytosis of Neisseria.

Strengths:

The article is overall well written, and it is a …

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

The work by Pinon et al describes the generation of a microvascular model to study Neisseria meningitidis interactions with blood vessels. The model uses a novel and relatively high throughput fabrication method that allows full control over the geometry of the vessels. The model is well characterized from the vascular standpoint and shows improvements when exposed to flow. The authors show that Neisseria binds to the 3D model in a similar geometry that in the animal xenograft model, induces an increase in permeability short after bacterial perfusion, and endothelial cytoskeleton rearrangements including a honeycomb actin structure. Finally, the authors show neutrophil recruitment to bacterial microcolonies and phagocytosis of Neisseria.

Strengths:

The article is overall well written, and it is a great advancement in the bioengineering and sepsis infection field. The authors achieved their aim at establishing a good model for Neisseria vascular pathogenesis and the results support the conclusions. I support the publication of the manuscript. I include below some clarifications that I consider would be good for readers.

One of the most novel things of the manuscript is the use of a relatively quick photoablation system. Could this technique be applied in other laboratories? While the revised manuscript includes more technical details as requested, the description remains difficult to follow for readers from a biology background. I recommend revising this section to improve clarity and accessibility for a broader scientific audience.

The authors suggest that in the animal model, early 3h infection with Neisseria do not show increase in vascular permeability, contrary to their findings in the 3D in vitro model. However, they show a non-significant increase in permeability of 70 KDa Dextran in the animal xenograft early infection. As a bioengineer this seems to point that if the experiment would have been done with a lower molecular weight tracer, significant increases in permeability could have been detected. I would suggest to do this experiment that could capture early events in vascular disruption.

One of the great advantages of the system is the possibility of visualizing infection-related events at high resolution. The authors show the formation of actin of a honeycomb structure beneath the bacterial microcolonies. This only occurred in 65% of the microcolonies. Is this result similar to in vitro 2D endothelial cultures in static and under flow? Also, the group has shown in the past positive staining of other cytoskeletal proteins, such as ezrin in the ERM complex. Does this also occur in the 3D system?

Significance:

The manuscript is comprehensive, complete and represents the first bioengineered model of sepsis. One of the major strengths is the carful characterization and benchmarking against the animal xenograft model. Beyond the technical achievement, the manuscript is also highly quantitative and includes advanced image analysis that could benefit many scientists. The authors show a quick photoablation method that would be useful for the bioengineering community and improved the state-of-the-art providing a new experimental model for sepsis.

My expertise is on infection bioengineered models.

Comments on revised version:

The authors have addressed all my concerns.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Pinon and colleagues have developed a Vessel-on-Chip model showcasing geometrical and physical properties similar to the murine vessels used in the study of systemic infections. The authors succeed on their aim of developing an complex, humanized, in vitro model that can faithfully recapitulate the hallmarks of systemic infections.

The vessel was created via highly controllable laser photoablation in a collagen matrix, subsequent seeding of human endothelial cells, and flow perfusion to induce mechanical cues. This model could be infected with Neisseria meningitidis as a model of systemic infection. In this model, microcolony formation and dynamics, and effects on the host were very similar to those described for the human skin xenograft mouse model (the current gold standard for systemic studies) and were …

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Pinon and colleagues have developed a Vessel-on-Chip model showcasing geometrical and physical properties similar to the murine vessels used in the study of systemic infections. The authors succeed on their aim of developing an complex, humanized, in vitro model that can faithfully recapitulate the hallmarks of systemic infections.

The vessel was created via highly controllable laser photoablation in a collagen matrix, subsequent seeding of human endothelial cells, and flow perfusion to induce mechanical cues. This model could be infected with Neisseria meningitidis as a model of systemic infection. In this model, microcolony formation and dynamics, and effects on the host were very similar to those described for the human skin xenograft mouse model (the current gold standard for systemic studies) and were consistent with observations made in patients. The model could also recapitulate the neutrophil response upon N. meningitidis systemic infection.

The claims and the conclusions are supported by the data, the methods are properly presented, and the data is analyzed adequately. The most important strength of this manuscript is the technology developed to build this model, which is impressive and very innovative. The Vessel-on-Chip can be tuned to acquire complex shapes and, according to the authors, the process has been optimized to produce models very quickly. This is a great advancement compared with the technologies used to produce other equivalent models. This model proves to be equivalent to the most advanced model used to date (skin xenograft mouse model). The human skin xenograft mouse model requires complex surgical techniques and has the practical and ethical limitations associated with the use of animals. However, the Vessel-on-chip model is free of ethical concerns, can be produced quickly, and allows to precisely tune the vessel's geometry and to perform higher resolution microscopy. Both models were comparable in terms of the hallmarks defining the disease, suggesting that the presented model can be an effective replacement of the animal use in this area. In addition, the Vessel-on-Chip allows to perform microscopy with higher resolution and ease, which can in turn allow more complex and precise image-based analysis. The authors leverage the image-based analysis to obtain further insights into the infection, highlighting the capabilities of the model in this aspect.

A limitation of this model is that it lacks the multicellularity that characterizes other similar models, which could be useful to research disease more extensively. However, the authors discuss the possibilities of adding other cells to the model, for example, fibroblasts. The methodology would allow for integrating many different types of cells into the model, which would increase the scope of scientific questions that can be addressed. In addition, the technology presented in the current paper is also difficult to adapt for standard biology labs. The methodology is complex and requires specialized equipment and personnel, which might hinder its widespread utilization of this model by researchers in the field.

This manuscript will be of interest for a specialized audience focusing on the development of microphysiological models. The technology presented here can be of great interest to researchers whose main area of interest is the endothelium and the blood vessels, for example, researchers on the study of systemic infections, atherosclerosis, angiogenesis, etc. This manuscript can have great applications for a broad audience focusing on vasculature research. Due to the high degree of expertise required to produce these models, this paper can present an interesting opportunity to begin collaborations with researchers dealing with a wide range of diseases, including atherosclerosis, cancer (metastasis), and systemic infections of all kinds.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

In this manuscript Pinon et al. describe the development of a 3D model of human vasculature within a microchip to study Neisseria meningitidis (Nm)- host interactions and validate it through its comparison to the current gold-standard model consisting of human skin engrafted onto a mouse. There is a pressing need for robust biomimetic models with which to study Nm-host interactions because Nm is a human-specific pathogen for which research has been primarily limited to simple 2D human cell culture assays. Their investigation relies primarily on data derived from microscopy and its quantitative analysis, which support the authors' goal of validating their Vessel-on-Chip (VOC) as a useful tool for studying vascular infections by Nm, and by extension, other pathogens associated with blood vessels.

Stren…

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

In this manuscript Pinon et al. describe the development of a 3D model of human vasculature within a microchip to study Neisseria meningitidis (Nm)- host interactions and validate it through its comparison to the current gold-standard model consisting of human skin engrafted onto a mouse. There is a pressing need for robust biomimetic models with which to study Nm-host interactions because Nm is a human-specific pathogen for which research has been primarily limited to simple 2D human cell culture assays. Their investigation relies primarily on data derived from microscopy and its quantitative analysis, which support the authors' goal of validating their Vessel-on-Chip (VOC) as a useful tool for studying vascular infections by Nm, and by extension, other pathogens associated with blood vessels.

Strengths:

• Introduces a novel human in vitro system that promotes control of experimental variables and permits greater quantitative analysis than previous models

• The VOC model is validated by direct comparison to the state-of-the-art human skin graft on mouse model

• The authors make significant efforts to quantify, model, and statistically analyze their data

• The laser ablation approach permits defining custom vascular architecture

• The VOC model permits the addition and/or alteration of cell types and microbes added to the model

• The VOC model permits the establishment of an endothelium developed by shear stress and active infusion of reagents into the systemWeaknesses:

• The VOC model contains one cell type, human umbilical cord vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs), while true vasculature contains a number of other cell types that associate with and affect the endothelium, such as smooth muscle cells, pericytes, and components of the immune system. However, adding such complexity may be a future goal of this VOC model.

Impact:

The VOC model presented by Pinon et al. is an exciting advancement in the set of tools available to study human pathogens interacting with the vasculature. This manuscript focuses on validating the model, and as such sets the foundation for impactful research in the future. Of particular value is the photoablation technique that permits the custom design of vascular architecture without the use of artificial scaffolding structures described in previously published works.

Comments on revised version:

The authors have nicely addressed my (and other reviewers') comments.

-

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

One of the most novel things of the manuscript is the use of a relatively quick photoablation system. Could this technique be applied in other laboratories? While the revised manuscript includes more technical details as requested, the description remains difficult to follow for readers from a biology background. I recommend revising this section to improve clarity and accessibility for a broader scientific audience.

As suggested, we have adapted the paragraph related to the photoablation technique in the Material & Method section, starting line 1147. We believe it is now easier to follow.

The authors suggest that in the animal model, early 3h infection with Neisseria do not show increase in vascular …

Author response:

The following is the authors’ response to the original reviews

Public Reviews:

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

One of the most novel things of the manuscript is the use of a relatively quick photoablation system. Could this technique be applied in other laboratories? While the revised manuscript includes more technical details as requested, the description remains difficult to follow for readers from a biology background. I recommend revising this section to improve clarity and accessibility for a broader scientific audience.

As suggested, we have adapted the paragraph related to the photoablation technique in the Material & Method section, starting line 1147. We believe it is now easier to follow.

The authors suggest that in the animal model, early 3h infection with Neisseria do not show increase in vascular permeability, contrary to their findings in the 3D in vitro model. However, they show a non-significant increase in permeability of 70 KDa Dextran in the animal xenograft early infection. As a bioengineer this seems to point that if the experiment would have been done with a lower molecular weight tracer, significant increases in permeability could have been detected. I would suggest to do this experiment that could capture early events in vascular disruption.

Comparing permeability under healthy and infected conditions using Dextran smaller than 70 kDa is challenging. Previous research (1) has shown that molecules below 70 kDa already diffuse freely in healthy tissue. Given this high baseline diffusion, we believe that no significant difference would be observed before and after N. meningitidis infection, and these experiments were not carried out. As discussed in the manuscript, bacteria-induced permeability in mice occurs at later time points, 16h post-infection, as shown previously (2). As discussed in the manuscript, this difference between the xenograft model and the chip could reflect the absence of various cell types present in the tissue parenchyma or simply vessel maturation time.

One of the great advantages of the system is the possibility of visualizing infection-related events at high resolution. The authors show the formation of actin in a honeycomb structure beneath the bacterial microcolonies. This only occurred in 65% of the microcolonies. Is this result similar to in vitro 2D endothelial cultures in static and under flow? Also, the group has shown in the past positive staining of other cytoskeletal proteins, such as ezrin, in the ERM complex. Does this also occur in the 3D system?

We imaged monolayers of endothelial cells in the flat regions of the chip (the two lateral channels) using the same microscopy conditions (i.e., Obj. 40X N.A. 1.05) that have been used to detect honeycomb structures in the 3D vessels in vitro. We showed that more than 56% of infected cells present these honeycomb structures in 2D, which is 13% less than in 3D, and is not significant due to the distributions of both populations. Thus, we conclude that under both in vitro conditions, 2D and 3D, the amount of infected cells exhibiting cortical plaques is similar. These results are in Figure 4E and S4B.

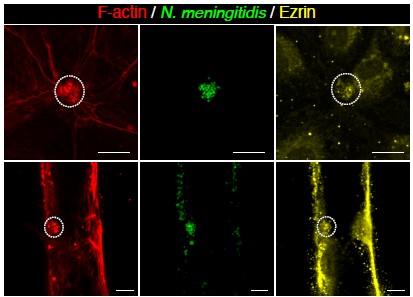

We also performed staining of ezrin in the chip and imaged both the 3D and 2D regions. Although ezrin staining was visible in 3D (Author response image 1), it was not as obvious as other markers under these infected conditions, and we did not include it in the main text. Interpretation of this result is not straightforward, as the substrate of the cells is different, and it would require further studies on the behavior of ERM proteins in these different contexts.

Author response image 1.

F-actin (red) and ezrin (yellow) staining after 3h of infection with N. meningitidis (green) in 2D (top) and 3D (bottom) vessel-on-chip models.

Recommendation to the authors:

Reviewer #1 (Recommendation to the authors):

I appreciate that the authors addressed most of my comments, of special relevance are the change of the title and references to infection-on-chip. I think that the current choice of words better acknowledges the incipient but strong bioengineering infection community. I also appreciate the inclusion of a limitation paragraph that better frames the current work and proposes future advancements.

The addition of more methodological details has improved the manuscript. Although as mentioned earlier the wording needs to be accessible for the biology community. I also appreciated the addition of the quantification of binding under the WSS gradient in the different geometries and shown in Fig 3H. However, the description of the figure and the legend is not clear. What does "vessel" mean on the graph and "normalized histograms ...(blue)" in the figure legend. Could the authors rephrase it?

In Figure 3F, we investigated whether Neisseria meningitidis exhibits preferential sites of infection. We hypothesized that, if bacteria preferentially adhered to specific regions, the local shear stress at these sites would differ from the overall distribution. To test this, we compared the shear stress at bacterial adhesion sites in the VoC (orange dots and curve) with the shear stress along the entire vascular edges (blue dots and curve). The high Spearman correlation indicates that there is no distinct shear stress value associated with bacterial adhesion. This suggests that bacteria can adhere across all regions, independently of local shear stress. To enhance clarity, the legend of Figure 3 and the related text have been rephrased in the revised manuscript (L289-314).

Line 415. Should reference to Fig S5B, not Fig 5B. Also, the titles in Supplementary Figure 4 and 5 are duplicated, and the description of the legend inf Fig S5 seems a bit off. A and B seem to be swapped.

Indeed, the reference to the right figure has been corrected. Also, the title of Figure S4 has been adapted to its contents, and the legend of Figure S5 has been corrected.

Reviewer #2 (Recommendation to the authors):

Minor comments to the authors:

Line 163 "they formed" instead of "formed".

Line 212 "two days" instead of "two day"

Line 269 a space between two words is missing.

These three comments have been addressed in the revised manuscript.

In addition, I appreciate answering the comments, especially those requiring hypothesizing about including further cells. However, when discussing which other cells could be relevant for the model (lines 631 to 632) it would be beneficial to discuss not only the role of those cells but also how could they be included in the model. I think for the reader, inclusion of further cells could be seen as a challenge or limitation, and addressing these technical points in the discussion could be helpful.

We thank Reviewer #2 for the insightful suggestion. Indeed, the method of introducing cells into the VoC depends on their type. Fibroblasts and dendritic cells, which are resident tissue cells, should be embedded in the collagen gel before polymerization and UV carving. This requires careful optimization to preserve chip integrity, as these cells exert pulling forces while migrating within the collagen matrix. In contrast, T cells and macrophages should be introduced through the vessel lumen to mimic their circulation in vivo. Pericytes can be co-seeded with endothelial cells, as they have been shown to self-organize within a few hours post-seeding. These important informations are now included in the manuscript (L577-587).

Reviewer #3 (Recommendation to the authors):

Suggestions and Recommendations

Some suggestions related to the VOC itself:

Figure 1, Fig S1, paragraph starting line 1071: More information would be helpful for the laser photoablation. For instance, is a non-standard UV laser needed? Which form of UV light is used? What is the frequency of laser pulsing? How many pulses/how long is needed to ablate the region of interest?

The photoablation process requires a focused UV-laser, with high frequency (10 kHz) to lower the carving time while providing the required intensity to degrade collagen gel. To carve a reproducible number of 30 µm-large vessels, we used a 2 µm-large laser beam at an energy of 10 mW and moved the stage (i.e., sample) at a maximum speed of 1 mm/s. This information has been added to the related paragraph starting on line 1147 of the revised manuscript.

It is difficult to understand the geometry of the VOC. In Figure 1C, is the light coloration representing open space through which medium can flow, and the dark section the collagen? On a single chip, how many vessels are cut through the collagen? It looks as if at least two are cut in Figure 1C in the righthand photo.

In Figure 1C, the light coloration is the Factin staining. The horizontal upper and lower parts are the 2D lateral channels that also contain endothelial cells, and are connected to inlets and outlets, respectively. In the middle, two vertically carved 3D vessels are shown in the confocal image.

Technically, we designed the PDMS structures to allow carving of 1 to 3 channels, maximizing the number of vessels that can be imaged while minimizing any loss of permeability at the PDMS/collagen/cells interface. This information has been added in the revised manuscript (L. 1147).

If multiple vessels are cut in the center channel between the lateral channels, how do you ensure that medium flow is even between all vessels? A single chip with multiple different vessel architectures through the center channel would be expected to have different hydrostatic resistance with different architectures, thereby causing differences in flow rates in each vessel.

To ensure a consistent flow rate regardless of the number of carved vessels, we opted to control the flow rate directly across the chip with a syringe pump. During experiments, one inlet and one outlet were closed, and a syringe pump was used. Because the carved vessels are arranged in parallel (derivation), the flow rate remains the same in each vessel. If a pressure controller had been used instead, the flow would have been distributed evenly across the different channels. This has been added to the revised manuscript in the paragraph starting on line 1210.

The figures imply that the laser ablation can be performed at depth within the collagen gel, rather than just etching the surface. If this is the case, it should be stated explicitly. If not, this needs to be clarified.

One of the main advantages of the photoablation technique is carving the collagen gel in volume, and not only etching the surface. Thanks to the 3D UV degradation, we can form the 3D architecture surrounded by the bulk collagen. This has been added to the revised manuscript, lines 154-155.

Is the in-vivo-like vessel architecture connected to the lateral channel at an oblique angle, or is the image turned to fit the entire structure? (Figure 1F and 3E). Is that why there is high shear stress at its junction with the lateral channel depicted in Figure 3E?

All structures require connection to the lateral channels to ensure media circulation and nutrient supply. The in vivo-like design must be rotated to allow the upper and lower branches of the complex structure to pass between the fixed PDMS pillars. To remain consistent with the image and the flow direction, we have kept the same orientation as in the COMSOL simulation. This leads to a locally higher shear stress at the top of the architecture. This has been added in the revised manuscript, in the paragraph starting on line 1474.

Figure S1F,G: In the legend, shapes are circles, not squares. On the graphs, what do the numbers in parentheses mean?

Indeed, the terms "squares" have been replaced by "circles" in Figure 1. (1) and (2) refer to the providers of the collagen, FujiFilm and Corning, respectively. We have added this mention in the legend in Figure S1.

Figure 3B: how do the images on the left and right differ? Each of the 4 images needs to be explained.

The four images represent the infected VoC from different viewing angles, illustrating the three-dimensional spread of infection throughout the vessel. A more detailed description has been added in the legend of Figure 3.

Figure S3C is not referenced but should be, likely before sentence starting on line 299.

Indeed, the reference to Figure S3C has been added line 301 of the revised manuscript.

Results in Figure 3 with the pilD mutant are very interesting. It is worth commenting in the Discussion about how T4P functionality in addition to the presence of T4P contributes to Nm infection, and how in the future this could be probed with pilT mutants.

We thank Reviewer #3 for this relevant insight. Following adhesion, a key functionality of Neisseria meningitidis for colony formation and enhanced infection is twitching motility. As suggested, we have added in the Discussion the idea of using a PilT mutant, which can adhere but cannot retract its pili, in the VoC model to investigate the role of motility in colonization in vitro under flow conditions (L611–623).

Which vessel design was used for the data presented in Figures 4, 5, and 6 and associated supplemental figures?

Straight channels have been mostly used in figures 4, 5, and 6. Rarely, we used the branched in vivo-like designs to observe potential similar infection patterns to in vivo, and related neutrophil activity. This has been added in the revised manuscript, lines 1435-1439.

Figure 4B-D: the images presented in Figure 4C are not representative of the averages presented in Figures 4B,D. For instance, the aggregates appear much larger and more elongated in the animal model in Figure 4C, but the animal model and VOC have the colony doubling time (implying same size) in Figure 4B, and same average aggregate elongation in Figure 4D.

The images in Figure 4C were selected to illustrate the elongation of colonies quantified in Figure 4D. The elongation angles are consistent between both images and align with the channel orientation. Representative images of colony expansion over time, corresponding to Figure 4A and 4B, are provided in Figure S4A.

Figures 4E-F: dextran does not appear to diffuse in the VOC in response to histamine in these images, yet there is a significant increase in histamine-induced permeability in Figure 4F. Dotted lines should be used to indicate vessel walls for histamine, and/or a more representative image should be selected. A control set of images should also be included for comparison.

We thank Reviewer #3 for the insightful comment. We confirm that we have carefully selected representative images for the histamine condition and adjusted them to display the same range of gray levels. The apparent increase in permeability with histamine is explained by a slight rise in background fluorescence, combined with the smaller channel size shown in Figure 4E.

Figure S4 title is a duplicate of Figure S5 and is unrelated to the content of Figure S4. Suggest rewording to mention changes in permeability induced by Nm infection in the VOC and animal model.

Indeed, the title of Figure S4 did not correspond to its content. We have, thus, changed it in the revised manuscript.

Line 489 "...our Vessel-on-Chip model has the potential to fully capture the human neutrophil response during vascular infections, in a species-matched microenvironment", is an overstatement. As presented, the VOC model only contains endothelial cells and neutrophils. Many other cell types and structures can affect neutrophil activity. Thus, it is an overstatement to claim that the model can fully capture the human neutrophil response.

We agree with the Reviewer #3, that neutrophil activity is fully recapitulated with other cell types, such as platelets, pericytes, macrophages, dendritic cells, and fibroblasts, that secrete important molecules such as cytokines, chemokines, TNF-α, and histamine. In our simplified model we were able to reconstitute the complex interaction of neutrophils with endothelial cells and with bacteria. The text was modified accordingly.

Supplemental Figure 6 - Does CD62E staining overlap with sites of Nm attachment

E-selectin staining does not systematically colocalize with Neisseria meningitidis colonies although bacterial adhesion is required. Its overall induced expression is heterogeneous across the tissue and shows heterogeneity from cell to cell as seen in vivo.

Line 475, Figure 6E- Phagocytosis of Nm is described, but it is difficult to see. An arrow should be added to make this clear. Perhaps the reference should have been to Figure 6G? Consider changing the colors in Figure 6G away from red/green to be more color-blind friendly.

Indeed, the reference to the right figure is Figure 6G, where the phagocytosis event is zoomed in. We have changed it in the text. Adapting the color of this figure 6G would imply to also change all the color codes of the manuscript, as red has been used for actin and green for Neisseria meningitidis.

Lines 621-632 - This important discussion point should be reworked. Some suggested references to cite and discuss include PMID: 7913984, 15186399, 17991045, 18640287, 19880493.

We have introduced in the discussion parts the following references as suggested (3–7), and discussed more the importance of introducting of immune cells to study immune cell-bacteria interaction and related immune response (L659-678).

Minor corrections:

• Line 8 - suggest "photoablation-generated" instead of "photoablation-based"

• Line 57- remove the word "either", or modify the sentence

• Sentence on lines 162-165 needs rewording

• Lines 204-205- "loss of vascular permeability" should read "increase in vascular permeability"

• Line 293- "Measured" shear stress, should be "computed", since it was not directly measured (according to the Materials & Methods)

• Line 304- "consistently" should be "consistent"

• Fig. 3 legend, second line: replace "our" with "the VoC"

• Line 371, change "our" to "the"

• Line 415- Figure 5B doesn’t appear to show 2-D data. Is this in Figure S5B? Some clarification is needed. The quantification of Nm vessel association in both the VOC and the animal model should be shown in Figure 5, for direct comparison.

• Supplementary Figure 5C: correlation coefficient with statistical significance should be calculated.

• Figure 6 title, rephrase to "The infected VOC model"

• Line 450, replace "important" with "statistically significant"

• Line 459, suggest rephrasing to "bacterial pilus-mediated adhesion"

• Line 533- grammar needs correction

• Line 589- should be "sheds"

• Line 1106- should be "pellet"

• Lines 1223-1224 - is the antibody solution introduced into the inlet of the VOC for staining? Please clarify.

• Line 1295-unclear why Figure 2B is being referenced here

All the suggested minor corrections have been taken into account in the revised manuscript.

References

(1) Gyohei Egawa, Satoshi Nakamizo, Yohei Natsuaki, Hiromi Doi, Yoshiki Miyachi, and Kenji Kabashima. Intravital analysis of vascular permeability in mice using two-photon microscopy. Scientific Reports, 3(1):1932, Jun 2013. ISSN 2045-2322. doi: 10.1038/srep01932.

(2) Valeria Manriquez, Pierre Nivoit, Tomas Urbina, Hebert Echenique-Rivera, Keira Melican, Marie-Paule Fernandez-Gerlinger, Patricia Flamant, Taliah Schmitt, Patrick Bruneval, Dorian Obino, and Guillaume Duménil. Colonization of dermal arterioles by neisseria meningitidis provides a safe haven from neutrophils. Nature Communications, 12(1):4547, Jul 2021. ISSN 2041-1723. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24797-z.

(3) Katherine A. Rhodes, Man Cheong Ma, María A. Rendón, and Magdalene So. Neisseria genes required for persistence identified via in vivo screening of a transposon mutant library. PLOS Pathogens, 18(5):1–30, 05 2022. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1010497.

(4) Heli Uronen-Hansson, Liana Steeghs, Jennifer Allen, Garth L. J. Dixon, Mohamed Osman, Peter Van Der Ley, Simon Y. C. Wong, Robin Callard, and Nigel Klein. Human dendritic cell activation by neisseria meningitidis: phagocytosis depends on expression of lipooligosaccharide (los) by the bacteria and is required for optimal cytokine production. Cellular Microbiology, 6(7):625–637, 2004. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-5822.2004.00387.x.

(5) M. C. Jacobsen, P. J. Dusart, K. Kotowicz, M. Bajaj-Elliott, S. L. Hart, N. J. Klein, and G. L. Dixon. A critical role for atf2 transcription factor in the regulation of e-selectin expression in response to non-endotoxin components of neisseria meningitidis. Cellular Microbiology, 18(1):66–79, 2016. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/cmi.12483.

(6) Andrea Villwock, Corinna Schmitt, Stephanie Schielke, Matthias Frosch, and Oliver Kurzai. Recognition via the class a scavenger receptor modulates cytokine secretion by human dendritic cells after contact with neisseria meningitidis. Microbes and Infection, 10(10):1158–1165, 2008. ISSN 1286-4579. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2008.06.009.

(7) Audrey Varin, Subhankar Mukhopadhyay, Georges Herbein, and Siamon Gordon. Alternative activation of macrophages by il-4 impairs phagocytosis of pathogens but potentiates microbial-induced signalling and cytokine secretion. Blood, 115(2):353–362, Jan 2010. ISSN 0006-4971. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-236711.

-

eLife Assessment

In this important study, the authors develop a microfluidic "Vessel-on-Chip" model to study Neisseria meningitidis interactions in an in vitro vascular system. Compelling evidence demonstrates that endothelial cell-lined channels can be colonized by N. meningitidis, triggering neutrophil recruitment with advantages over complex surgical xenograft models. This system offers potential for follow-on studies of N. meningitidis pathogenesis, though it lacks the cellular complexity of true vasculature including smooth muscle cells and pericytes.

[Editors' note: this paper was reviewed by Review Commons.]

-

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

The work by Pinon et al describes the generation of a microvascular model to study Neisseria meningitidis interactions with blood vessels. The model uses a novel and relatively high throughput fabrication method that allows full control over the geometry of the vessels. The model is well characterized from the vascular standpoint and shows improvements when exposed to flow. The authors show that Neisseria binds to the 3D model in a similar geometry that in the animal xenograft model, induces an increase in permeability short after bacterial perfusion, and endothelial cytoskeleton rearrangements including a honeycomb actin structure. Finally, the authors show neutrophil recruitment to bacterial microcolonies and phagocytosis of Neisseria.

Strengths:

The article is overall well written, and it is a …

Reviewer #1 (Public review):

Summary:

The work by Pinon et al describes the generation of a microvascular model to study Neisseria meningitidis interactions with blood vessels. The model uses a novel and relatively high throughput fabrication method that allows full control over the geometry of the vessels. The model is well characterized from the vascular standpoint and shows improvements when exposed to flow. The authors show that Neisseria binds to the 3D model in a similar geometry that in the animal xenograft model, induces an increase in permeability short after bacterial perfusion, and endothelial cytoskeleton rearrangements including a honeycomb actin structure. Finally, the authors show neutrophil recruitment to bacterial microcolonies and phagocytosis of Neisseria.

Strengths:

The article is overall well written, and it is a great advancement in the bioengineering and sepsis infection field. The authors achieved their aim at establishing a good model for Neisseria vascular pathogenesis and the results support the conclusions. I support the publication of the manuscript. I include below some clarifications that I consider would be good for readers.

One of the most novel things of the manuscript is the use of a relatively quick photoablation system. Could this technique be applied in other laboratories? While the revised manuscript includes more technical details as requested, the description remains difficult to follow for readers from a biology background. I recommend revising this section to improve clarity and accessibility for a broader scientific audience.

The authors suggest that in the animal model, early 3h infection with Neisseria do not show increase in vascular permeability, contrary to their findings in the 3D in vitro model. However, they show a non-significant increase in permeability of 70 KDa Dextran in the animal xenograft early infection. As a bioengineer this seems to point that if the experiment would have been done with a lower molecular weight tracer, significant increases in permeability could have been detected. I would suggest to do this experiment that could capture early events in vascular disruption.

One of the great advantages of the system is the possibility of visualizing infection-related events at high resolution. The authors show the formation of actin of a honeycomb structure beneath the bacterial microcolonies. This only occurred in 65% of the microcolonies. Is this result similar to in vitro 2D endothelial cultures in static and under flow? Also, the group has shown in the past positive staining of other cytoskeletal proteins, such as ezrin in the ERM complex. Does this also occur in the 3D system?

Significance:

The manuscript is comprehensive, complete and represents the first bioengineered model of sepsis. One of the major strengths is the carful characterization and benchmarking against the animal xenograft model. Beyond the technical achievement, the manuscript is also highly quantitative and includes advanced image analysis that could benefit many scientists. The authors show a quick photoablation method that would be useful for the bioengineering community and improved the state-of-the-art providing a new experimental model for sepsis.

My expertise is on infection bioengineered models.

-

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Pinon and colleagues have developed a Vessel-on-Chip model showcasing geometrical and physical properties similar to the murine vessels used in the study of systemic infections. The vessel was created via highly controllable laser photoablation in a collagen matrix, subsequent seeding of human endothelial cells, and flow perfusion to induce mechanical cues. This model could be infected with Neisseria meningitidis as a model of systemic infection. In this model, microcolony formation and dynamics, and effects on the host were very similar to those described for the human skin xenograft mouse model (the current gold standard for systemic studies) and were consistent with observations made in patients. The model could also recapitulate the neutrophil response upon N. meningitidis systemic infection.

The claims …

Reviewer #2 (Public review):

Pinon and colleagues have developed a Vessel-on-Chip model showcasing geometrical and physical properties similar to the murine vessels used in the study of systemic infections. The vessel was created via highly controllable laser photoablation in a collagen matrix, subsequent seeding of human endothelial cells, and flow perfusion to induce mechanical cues. This model could be infected with Neisseria meningitidis as a model of systemic infection. In this model, microcolony formation and dynamics, and effects on the host were very similar to those described for the human skin xenograft mouse model (the current gold standard for systemic studies) and were consistent with observations made in patients. The model could also recapitulate the neutrophil response upon N. meningitidis systemic infection.

The claims and the conclusions are supported by the data, the methods are properly presented, and the data is analyzed adequately. The most important strength of this manuscript is the technology developed to build this model, which is impressive and very innovative. The Vessel-on-Chip can be tuned to acquire complex shapes and, according to the authors, the process has been optimized to produce models very quickly. This is a great advancement compared with the technologies used to produce other equivalent models. This model proves to be equivalent to the most advanced model used to date (skin xenograft mouse model). The human skin xenograft mouse model requires complex surgical techniques and has the practical and ethical limitations associated with the use of animals. However, the Vessel-on-chip model is free of ethical concerns, can be produced quickly, and allows to precisely tune the vessel's geometry and to perform higher resolution microscopy. Both models were comparable in terms of the hallmarks defining the disease, suggesting that the presented model can be an effective replacement of the animal use in this area. In addition, the Vessel-on-Chip allows to perform microscopy with higher resolution and ease, which can in turn allow more complex and precise image-based analysis.

A limitation of this model is that it lacks the multicellularity that characterizes other similar models, which could be useful to research disease more extensively. However, the authors discuss the possibilities of adding other cells to the model, for example, fibroblasts. It is also not clear whether the technology presented in the current paper can be adopted by other labs. The methodology is complex and requires specialized equipment and personnel, which might hinder its widespread utilization of this model by researchers in the field.

This manuscript will be of interest for a specialized audience focusing on the development of microphysiological models. The technology presented here can be of great interest to researchers whose main area of interest is the endothelium and the blood vessels, for example, researchers on the study of systemic infections, atherosclerosis, angiogenesis, etc. This manuscript can have great applications for a broad audience and it can present an opportunity to begin collaborations, aimed at answering diverse research questions with the same model.

-

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

In this manuscript Pinon et al. describe the development of a 3D model of human vasculature within a microchip to study Neisseria meningitidis (Nm)- host interactions and validate it through its comparison to the current gold-standard model consisting of human skin engrafted onto a mouse. There is a pressing need for robust biomimetic models with which to study Nm-host interactions because Nm is a human-specific pathogen for which research has been primarily limited to simple 2D human cell culture assays. Their investigation relies primarily on data derived from microscopy and its quantitative analysis, which support the authors' goal of validating their Vessel-on-Chip (VOC) as a useful tool for studying vascular infections by Nm, and by extension, other pathogens associated with blood vessels.

Stren…

Reviewer #3 (Public review):

Summary:

In this manuscript Pinon et al. describe the development of a 3D model of human vasculature within a microchip to study Neisseria meningitidis (Nm)- host interactions and validate it through its comparison to the current gold-standard model consisting of human skin engrafted onto a mouse. There is a pressing need for robust biomimetic models with which to study Nm-host interactions because Nm is a human-specific pathogen for which research has been primarily limited to simple 2D human cell culture assays. Their investigation relies primarily on data derived from microscopy and its quantitative analysis, which support the authors' goal of validating their Vessel-on-Chip (VOC) as a useful tool for studying vascular infections by Nm, and by extension, other pathogens associated with blood vessels.

Strengths:

• Introduces a novel human in vitro system that promotes control of experimental variables and permits greater quantitative analysis than previous models

• The VOC model is validated by direct comparison to the state-of-the-art human skin graft on mouse model

• The authors make significant efforts to quantify, model, and statistically analyze their data

• The laser ablation approach permits defining custom vascular architecture

• The VOC model permits the addition and/or alteration of cell types and microbes added to the model

• The VOC model permits the establishment of an endothelium developed by shear stress and active infusion of reagents into the systemWeaknesses:

• The work presented here is mostly descriptive, with little new information that is learned about the biology of Nm or endothelial cells. However, the goal of this study was to establish the VOC model, and the validation presented here is necessary for follow-on studies on Nm pathogenesis and host response.

• The VOC model contains one cell type, human umbilical cord vascular endothelial cells (HUVECs), while true vasculature contains a number of other cell types that associate with and affect the endothelium, such as smooth muscle cells, pericytes, and components of the immune system. These and other shortcomings of the VOC model as it currently stands warrant additional discussion.Impact:

The VOC model presented by Pinon et al. is an exciting advancement in the set of tools available to study human pathogens interacting with the vasculature. This manuscript focuses on validating the model, and as such sets the foundation for impactful research in the future. Of particular value is the photoablation technique that permits the custom design of vascular architecture without the use of artificial scaffolding structures described in previously published works. -

Author response:

Point-by-point description of the revisions

Reviewer #1 (Evidence, reproducibility, and clarity):

The work by Pinon et al describes the generation of a microvascular model to study Neisseria meningitidis interactions with blood vessels. The model uses a novel and relatively high throughput fabrication method that allows full control over the geometry of the vessels. The model is well characterized. The authors then study different aspects of Neisseriaendothelial interactions and benchmark the bacterial infection model against the best disease model available, a human skin xenograft mouse model, which is one of the great strengths of the paper. The authors show that Neisseria binds to the 3D model in a similar geometry that in the animal xenograft model, induces an increase in permeability short after bacterial …

Author response:

Point-by-point description of the revisions

Reviewer #1 (Evidence, reproducibility, and clarity):

The work by Pinon et al describes the generation of a microvascular model to study Neisseria meningitidis interactions with blood vessels. The model uses a novel and relatively high throughput fabrication method that allows full control over the geometry of the vessels. The model is well characterized. The authors then study different aspects of Neisseriaendothelial interactions and benchmark the bacterial infection model against the best disease model available, a human skin xenograft mouse model, which is one of the great strengths of the paper. The authors show that Neisseria binds to the 3D model in a similar geometry that in the animal xenograft model, induces an increase in permeability short after bacterial perfusion, and induces endothelial cytoskeleton rearrangements. Finally, the authors show neutrophil recruitment to bacterial microcolonies and phagocytosis of Neisseria. The article is overall well written, and it is a great advancement in the bioengineering and sepsis infection field, and I only have a few major comments and some minor.

Major comments:

Infection-on-chip. I would recommend the authors to change the terminology of "infection on chip" to better reflect their work. The term is vague and it decreases novelty, as there are multiple infection on chips models that recapitulate other infections (recently reviewed in https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-024-01645-6) including Ebola, SARS-CoV-2, Plasmodium and Candida. Maybe the term "sepsis on chip" would be more specific and exemplify better the work and novelty. Also, I would suggest that the authors carefully take a look at the text and consider when they use VoC or to current term IoC, as of now sometimes they are used interchangeably, with VoC being used occasionally in bacteria perfused experiments.

We thank Reviewer #1 for this suggestion. Indeed, we have chosen to replace the term "Infection-on-Chip" by "infected Vessel-on-chip" to avoid any confusion in the title and the text. Also, we have removed all the terms "IoC" which referred to "Infection-on-Chip" and replaced with "VoC" for "Vessel-on-Chip". We think these terms will improve the clarity of the main text.

Author response image 1.

F-actin (red) and ezrin (yellow) staining after 3h of infection with N. meningitidis (green) in 2D (top) and 3D (bottom) vessel-on-chip models.

Fig 3 and Supplementary 3: Permeability. The authors suggest that early 3h infection with Neisseria do not show increase in vascular permeability in the animal model, contrary to their findings in the 3D in vitro model. However, they show a non-significant increase in permeability of 70 KDa Dextran in the animal xenograft early infection. This seems to point that if the experiment would have been done with a lower molecular weight tracer, significant increases in permeability could have been detected. I would suggest to do this experiment that could capture early events in vascular disruption.

Comparing permeability under healthy and infected conditions using Dextran smaller than 70 kDa is challenging. Previous research (1) has shown that molecules below 70 kDa already diffuse freely in healthy tissue. Given this high baseline diffusion, we believe that no significant difference would be observed before and after N. meningitidis infection and these experiments were not carried out. As discussed in the manuscript, bacteria induced permeability in mouse occurs at later time points, 16h post infection as shown previoulsy (2). As discussed in the manuscript, this difference between the xenograft model and the chip likely reflect the absence in the chip of various cell types present in the tissue parenchyma.

The authors show the formation of actin of a honeycomb structure beneath the bacterial microcolonies. This only occurred in 65% of the microcolonies. Is this result similar to in vitro 2D endothelial cultures in static and under flow? Also, the group has shown in the past positive staining of other cytoskeletal proteins, such as ezrin in the ERM complex. Does this also occur in the 3D system?

We thank the Reviewer #1 for this suggestion.

• According to this recommendation, we imaged monolayers of endothelial cells in the flat regions of the chip (the two lateral channels) using the same microscopy conditions (i.e., Obj. 40X N.A. 1.05) that have been used to detect honeycomb structures in the 3D vessels in vitro. We showed that more than 56% of infected cells present these honeycomb structures in 2D, which is 13% less than in 3D, and is not significant due to the distributions of both populations. Thus, we conclude that under both in vitro conditions, 2D and 3D, the amount of infected cells exhibiting cortical plaques is similar. We have added the graph and the confocal images in Figure S4B and lines 418-419 of the revised manuscript.

• We recently performed staining of ezrin in the chip and imaged both the 3D and 2D regions. Although ezrin staining was visible in 3D (Fig. 1 of this response), it was not as obvious as other markers under these infected conditions and we did not include it in the main text. Interpretation of this result is not straight forward as for instance the substrate of the cells is different and it would require further studies on the behaviour of ERM proteins in these different contexts.

One of the most novel things of the manuscript is the use of a relatively quick photoablation system. I would suggest that the authors add a more extensive description of the protocol in methods. Could this technique be applied in other laboratories? If this is a major limitation, it should be listed in the discussion.

Following the Reviewer’s comment, we introduced more detailed explanations regarding the photoablation:

• L157-163 (Results): "Briefly, the chosen design is digitalized into a list of positions to ablate. A pulsed UV-LASER beam is injected into the microscope and shaped to cover the back aperture of the objective. The laser is then focused on each position that needs ablation. After introducing endothelial cells (HUVEC) in the carved regions,…"

• L512-516 (Discussion): "The speed capabilities drastically improve with the pulsing repetition rate. Given that our laser source emits pulses at 10kHz, as compared to other photoablation lasers with repetitions around 100 Hz, our solution could potentially gain a factor of 100."

• L1082-1087 (Materials and Methods): "…, and imported in a python code. The control of the various elements is embedded and checked for this specific set of hardware. The code is available upon request." Adding these three paragraphs gives more details on how photoablation works thus improving the manuscript.

Minor comments:

Supplementary Fig 2. The reference to subpanels H and I is swapped.

The references to subpanels H and I have been correctly swapped back in the reviewed version.

Line 203: I would suggest to delete this sentence. Although a strength of the submitted paper is the direct comparison of the VoC model with the animal model to better replicate Neisseria infection, a direct comparison with animal permeability is not needed in all vascular engineering papers, as vascular permeability measurements in animals have been well established in the past.

The sentence "While previously developed VoC platforms aimed at replicating physiological permeability properties, they often lack direct comparisons with in vivo values." has been removed from the revised text.

Fig 3: Bacteria binding experiments. I would suggest the addition of more methodological information in the main results text to guarantee a good interpretation of the experiment. First, it would be better that wall shear stress rather than flow rate is described in the main text, as flow rate is dependent on the geometry of the vessel being used. Second, how long was the perfusion of Neisseria in the binding experiment performed to quantify colony doubling or elongation? As per figure 1C, I would guess than 100 min, but it would be better if this information is directly given to the readers.

We thank Reviewer #1 for these two suggestions that will improve the text clarity (e.g., L316). (i) Indeed, we have changed the flow rate in terms of shear stress. (ii) Also, we have normalized the quantification of the colony doubling time according to the first time-point where a single bacteria is attached to the vessel wall. Thus, early adhesion bacteria will be defined by a longer curve while late adhesion bacteria by a shorter curve. In total, the experiment lasted for 3 hours (modifications appear in L318 and L321-326).

Fig 4: The honeycomb structure is not visible in the 3D rendering of panel D. I would recommend to show the actin staining in the absence of Neisseria staining as well.

According to this suggestion, a zoom of the 3D rendering of the cortical plaque without colony had been added to the figure 4 of the revised manuscript.

Line 421: E-selectin is referred as CD62E in this sentence. I would suggest to use the same terminology everywhere.

We have replaced the "CD62E" term with "E-selectin" to improve clarity.

Line 508: "This difference is most likely associated with the presence of other cell types in the in vivo tissues and the onset of intravascular coagulation". Do the authors refer to the presence of perivascular cells, pericytes or fibroblasts? If so, it could be good to mention them, as well as those future iterations of the model could include the presence of these cell types.

By "other cell types", we refer to pericytes (3), fibroblasts (4), and perivascular macrophages (5), which surround endothelial cells and contribute to vessel stability. The main text was modified to include this information (Lines 548 and 555-570) and their potential roles during infection disussed.

Discussion: The discussion covers very well the advantages of the model over in vitro 2D endothelial models and the animal xenograft but fails to include limitations. This would include the choice of HUVEC cells, an umbilical vein cell line to study microcirculation, the lack of perivascular cells or limitations on the fabrication technique regarding application in other labs (if any).

We thank Reviewer #1 for this suggestion. Indeed, our manuscript may lack explaining limitations, and adding them to the text will help improve it:

• The perspectives of our model include introducing perivascular cells surrounding the vessel and fibroblasts into the collagen gel as discussed previously and added in the discussion part (L555-570).

• Our choice for HUVEC cells focused on recapitulating the characteristics of venules that respect key features such as the overexpression of CD62E and adhesion of neutrophils during inflammation. Using microvascular endothelial cells originating from different tissues would be very interesting. This possibility is now mentioned in the discussion lines 567-568.

• Photoablation is a homemade fabrication technique that can be implemented in any lab harboring an epifluorescence microscope. This method has been more detailed in the revised manuscript (L1085-1087).

Line 576: The authors state that the model could be applied to other systemic infections but failed to mention that some infections have already been modelled in 3D bioengineered vascular models (examples found in https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-024-01645-6). This includes a capillary photoablated vascular model to study malaria (DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aay724).

Thes two important references have been introduced in the main text (L84, 647, 648).

Line 1213: Are the 6M neutrophil solution in 10ul under flow. Also, I would suggest to rewrite this sentence in the following line "After, the flow has been then added to the system at 0.7-1 µl/min."

We now specified that neutrophils are circulated in the chip under flow conditions, lines 1321-1322.

Significance

The manuscript is comprehensive, complete and represents the first bioengineered model of sepsis. One of the major strengths is the carful characterization and benchmarking against the animal xenograft model. Its main limitations is the brief description of the photoablation methodology and more clarity is needed in the description of bacteria perfusion experiments, given their complexity. The manuscript will be of interest for the general infection community and to the tissue engineering community if more details on fabrication methods are included. My expertise is on infection bioengineered models.

Reviewer #2 (Evidence, reproducibility, and clarity):

Summary:

The authors develop a Vessel-on-Chip model, which has geometrical and physical properties similar to the murine vessels used in the study of systemic infections. The vessel was created via highly controllable laser photoablation in a collagen matrix, subsequent seeding of human endothelial cells and flow perfusion to induce mechanical cues. This vessel could be infected with Neisseria meningitidis, as a model of systemic infection. In this model, microcolony formation and dynamics, and effects on the host were very similar to those described for the human skin xenograft mouse, which is the current gold standard for these studies, and were consistent with observations made in patients. The model could also recapitulate the neutrophil response upon N. meningitidis systemic infection.

Major comments:

I have no major comments. The claims and the conclusions are supported by the data, the methods are properly presented and the data is analyzed adequately. Furthermore, I would like to propose an optional experiment could improve the manuscript. In the discussion it is stated that the vascular geometry might contribute to bacterial colonization in areas of lower velocity. It would be interesting to recapitulate this experimentally. It is of course optional but it would be of great interest, since this is something that can only be proven in the organ-on-chip (where flow speed can be tuned) and not as much in animal models. Besides, it would increase impact, demonstrating the superiority of the chip in this area rather than proving to be equal to current models.

We have conducted additional experiments on infection in different vascular geometries now added these results figure 3/S3 and lines 288-305. We compared sheared stress levels as determined by Comsol simulation and experimentally determined bacterial adhesion sites. In the conditions used, the range of shear generated by the tested geometries do not appear to change the efficiency of bacterial adhesion. These results are consistent with a previous study from our group which show that in this range of shear stresses the effect on adhesion is limited (6) . Furthermore, qualitative observations in the animal model indicate that bacteria do not have an obvious preference in terms of binding site.

Minor comments:

I have a series of suggestions which, in my opinion, would improve the discussion. They are further elaborated in the following section, in the context of the limitations.

• How to recapitulate the vessels in the context of a specific organ or tissue? If the pathogen is often found in the luminal space of other organs after disseminating from the blood, how can this process be recapitulated with this mode, if at all?

For reasons that are not fully understood, postmortem histological studies reveal bacteria only inside blood vessels but rarely if ever in the organ parenchyma. The presence of intravascular bacteria could nevertheless alter cells in the tissue parenchyma. The notable exception is the brain where bacteria exit the bacterial lumen to access the cerebrospinal fluid. The chip we describe is fully adapted to develop a blood brain barrier model and more specific organ environments. This implies the addition of more cell types in the hydrogel. A paragraph on this topic has been added (Lines 548 and 552-570).

• Similarly, could other immune responses related to systemic infection be recapitulated? The authors could discuss the potential of including other immune cells that might be found in the interstitial space, for example.

This important discussion point has been added to the manuscript (L623-636). As suggested by Reviewer #2, other immune cells respond to N. meningitis and can be explored using our model. For instance, macrophages and dendritic cells are activated upon N. meningitis infection, eliminate the bacteria through phagocytosis, produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines potentially activating lymphocytes (7). Such an immune response, yet complex, would be interesting to study in our model as skin-xenograft mice are deprived of B and T lymphocytes to ensure acceptance of human skin grafts.

• A minor correction: in line 467 it should probably be "aspects" instead of "aspect", and the authors could consider rephrasing that sentence slightly for increased clarity.

We have corrected the sentence with "we demonstrated that our VoC strongly replicates key aspects of the in vivo human skin xenograft mouse model, the gold standard for studying meningococcal disease under physiological conditions." in lines 499-503.

Strengths and limitations

The most important strength of this manuscript is the technology they developed to build this model, which is impressive and very innovative. The Vessel-on-Chip can be tuned to acquire complex shapes and, according to the authors, the process has been optimized to produce models very quickly. This is a great advancement compared with the technologies used to produce other equivalent models. This model proves to be equivalent to the most advanced model used to date, but allows to perform microscopy with higher resolution and ease, which can in turn allow more complex and precise image-based analysis. However, the authors do not seem to present any new mechanistic insights obtained using this model. All the findings obtained in the infection-on-chip demonstrate that the model is equivalent to the human skin xenograft mouse model, and can offer superior resolution for microscopy. However, the advantages of the model do not seem to be exploited to obtain more insights on the pathogenicity mechanisms of N. meningitidis, host-pathogen interactions or potential applications in the discovery of potential treatments. For example, experiments to elucidate the role of certain N. meningiditis genes on infection could enrich the manuscript and prove the superiority of the model. However, I understand these experiments are time-consuming and out of the scope of the current manuscript. In addition, the model lacks the multicellularity that characterizes other similar models. The authors mention that the pathogen can be found in the luminal space of several organs, however, this luminal space has not been recapitulated in the model. Even though this would be a new project, it would be interesting that the authors hypothesize about the possibilities of combining this model with other organ models. The inclusion of circulating neutrophils is a great asset; however it would also be interesting to hypothesize about how to recapitulate other immune responses related to systemic infection.

We thank Reviewer #2 for his/her comment on the strengths and limitations of our work. The difficulty is that our study opens many futur research directions and applications and we hope that the work serves as the basis for many future studies but one can only address a limited set of experiments in a single manuscript.

• Experiments investigating the role of N. meningitidis genes require significant optimization of the system. Multiplexing is a potential avenue for future development, which would allow the testing of many mutants. The fast photoablation approach is particularly amenable to such adaptation.

• Cells and bacteria inside the chambers could be isolated and analyzed at the transcriptomic level or by flow cytometry. This would imply optimizing a protocol for collecting cells from the device via collagenase digestion, for instance. This type of approach would also benefit from multiplexing to enhance the number of cells.

• As mentioned above, the revised manuscript discusses the multicellular capabilities of our model, including the integration of additional immune cells and potential connections to other organ systems. We believe that these approaches are feasible and valuable for studying various aspects of N. meningitidis infection.

Advance

The most important advance of this manuscript is technical: the development of a model that proves to be equivalent to the most complex model used to date to study meningococcal systemic infections. The human skin xenograft mouse model requires complex surgical techniques and has the practical and ethical limitations associated with the use of animals. However, the Infection-on-chip model is completely in vitro, can be produced quickly, and allows to precisely tune the vessel’s geometry and to perform higher resolution microscopy. Both models were comparable in terms of the hallmarks defining the disease, suggesting that the presented model can be an effective replacement of the animal use in this area.

Other vessel-on-chip models can recapitulate an endothelial barrier in a tube-like morphology, but do not recapitulate other complex geometries, that are more physiologically relevant and could impact infection (in addition to other non-infectious diseases). However, in the manuscript it is not clear whether the different morphologies are necessary to study or recapitulate N. meningitidis infection, or if the tubular morphologies achieved in other similar models would suffice.

Audience

This manuscript might be of interest for a specialized audience focusing on the development of microphysiological models. The technology presented here can be of great interest to researchers whose main area of interest is the endothelium and the blood vessels, for example, researchers on the study of systemic infections, atherosclerosis, angiogenesis, etc. Thus, the tool presented (vessel-on-chip) can have great applications for a broad audience. However, even when the method might be faster and easier to use than other equivalent methods, it could still be difficult to implement in another laboratory, especially if it lacks expertise in bioengineering. Therefore, the method could be more of interest for laboratories with expertise in bioengineering looking to expand or optimize their toolbox. Alternatively, this paper present itself as an opportunity to begin collaborations, since the model could be used to test other pathogen or conditions.

Field of expertise:

Infection biology, organ-on-chip, fungal pathogens.

I lack the expertise to evaluate the image-based analysis.

References

(1) Gyohei Egawa, Satoshi Nakamizo, Yohei Natsuaki, Hiromi Doi, Yoshiki Miyachi, and Kenji Kabashima. Intravital analysis of vascular permeability in mice using two-photon microscopy. Scientific Reports, 3(1):1932, Jun 2013. ISSN 2045-2322. doi: 10.1038/srep01932.

(2) Valeria Manriquez, Pierre Nivoit, Tomas Urbina, Hebert Echenique-Rivera, Keira Melican, Marie-Paule Fernandez-Gerlinger, Patricia Flamant, Taliah Schmitt, Patrick Bruneval, Dorian Obino, and Guillaume Duménil. Colonization of dermal arterioles by neisseria meningitidis provides a safe haven from neutrophils. Nature Communications, 12(1):4547, Jul 2021. ISSN 2041-1723. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24797-z.

(3) Mats Hellström, Holger Gerhardt, Mattias Kalén, Xuri Li, Ulf Eriksson, Hartwig Wolburg, and Christer Betsholtz. Lack of pericytes leads to endothelial hyperplasia and abnormal vascular morphogenesis. Journal of Cell Biology, 153(3):543–554, Apr 2001. ISSN 0021-9525. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.3.543.

(4) Arsheen M. Rajan, Roger C. Ma, Katrinka M. Kocha, Dan J. Zhang, and Peng Huang. Dual function of perivascular fibroblasts in vascular stabilization in zebrafish. PLOS Genetics, 16(10):1–31, 10 2020. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008800.

(5) Huanhuan He, Julia J. Mack, Esra Güç, Carmen M. Warren, Mario Leonardo Squadrito, Witold W. Kilarski, Caroline Baer, Ryan D. Freshman, Austin I. McDonald, Safiyyah Ziyad, Melody A. Swartz, Michele De Palma, and M. Luisa Iruela-Arispe. Perivascular macrophages limit permeability. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology, 36(11):2203–2212, 2016. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA. 116.307592.

(6) Emilie Mairey, Auguste Genovesio, Emmanuel Donnadieu, Christine Bernard, Francis Jaubert, Elisabeth Pinard, Jacques Seylaz, Jean-Christophe Olivo-Marin, Xavier Nassif, and Guillaume Dumenil. Cerebral microcirculation shear stress levels determine Neisseria meningitidis attachment sites along the blood–brain barrier . Journal of Experimental Medicine, 203(8):1939–1950, 07 2006. ISSN 0022-1007. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060482.

(7) Riya Joshi and Sunil D. Saroj. Survival and evasion of neisseria meningitidis from macrophages. Medicine in Microecology, 17:100087, 2023. ISSN 2590-0978. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medmic. 2023.100087.

-

-

Note: This response was posted by the corresponding author to Review Commons. The content has not been altered except for formatting.

Learn more at Review Commons

Reply to the reviewers

Reviewer #1

Evidence, reproducibility, and clarity

The work by Pinon et al describes the generation of a microvascular model to study Neisseria meningitidis interactions with blood vessels. The model uses a novel and relatively high throughput fabrication method that allows full control over the geometry of the vessels. The model is well characterized. The authors then study different aspects of Neisseria-endothelial interactions and benchmark the bacterial infection model against the best disease model available, a human skin xenograft mouse model, which is one of the great strengths of the paper. The authors show that Neisseria binds to the 3D …

Note: This response was posted by the corresponding author to Review Commons. The content has not been altered except for formatting.

Learn more at Review Commons

Reply to the reviewers

Reviewer #1

Evidence, reproducibility, and clarity